To the Editors:

Martin Malia asks [“Lenin and the ‘Radiant Future,'” NYR, November 1] whether we can say “no Lenin, no communism.” Surely all attempts to answer must take account not only of him but also of the other prominent Bolsheviks of the critical day. When he returned to Russia in April 1917 with his astonishing call for an immediate seizure of power, an old Bolshevik who’d long supported his hard lines expressed the general outrage by denouncing “the delirium of a madman.” E.H. Carr would call the new arrival “completely isolated” at that point—isolated not only from other parties but also from his own extreme one. Solid Bolshevik opinion, stiffened by the arguments of all the lesser leaders, opposed him. After discussion, the Petrograd committee rejected his call by a vote of thirteen to two. That is of course not to say he didn’t then advance and retreat with what Pravda called his “unacceptable” ideas, depending on his reading of the circumstances, nor that one or another form of communism might not have come at a later time—but not the one that did come six months after his return. So isn’t the “big question” forced? If ever events depend on a single person’s notions, will, and skills, didn’t they then?

George Feifer

Roxbury, Connecticut

To the Editors:

In “Lenin and the ‘Radiant Future,'” Professor Malia ably describes the limited degree of Lenin’s dependence upon the writings of Karl Marx. At the same time, he indicates that The Communist Manifesto’s characterization of the Communists as that single party “understanding the lines of march” ahead of all other parties seemingly anticipates Lenin’s own concept of a dominant, elitist party, viz., the Bolshevik wing of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party.

Indeed, by a red thread this Marxist characterization in the Manifesto leads to Lenin’s main argument in his germinal 1902 work, What Is to Be Done? (said by Havana hagiographers to be Fidel Castro’s favorite political writing). Namely, as Lenin insisted, in order for the proletariat to acquire revolutionary consciousness, such consciousness must be “instilled” in them by the elitist Communist Party “from the outside.” Russian workers and poor peasants cannot on their own “spontaneously” develop such consciousness. Nor could they acquire it via a German Social Democratic– type labor movement in tandem with democratic parliamentarism.

In his book, Russia Under Western Eyes: From the Bronze Horseman to the Lenin Mausoleum (p. 169), Professor Malia, citing in a footnote (p. 467) my book on P.N. Tkachev, gave passing reference to the People’s Will movement of the 1870s. Malia likewise cited this movement in his NYR review as being an important influence on Lenin’s thinking in his youth.

This is putting it mildly. According to his chief librarian in Geneva, V.D. Bonch-Bruyevich (to cite one authority), Lenin consumed all the works of Petr Nikitich Tkachev (1844–1886). He found in them, “B.B.” disclosed,” Lenin’s own essential point of view. As Lenin advised newly arrived Russian exiles to Switzerland, “Begin by reading and familiarizing yourself with Tkachev’s Nabat [‘Tocsin’]: It is basic and will give you tremendous knowledge.” Lenin’s deep reading of some six volumes of Tkachev’s works, whom one Russian publicist of the early 1920s described bravely as the “first Bolshevik,” probably, in fact, inspired Lenin to pen What Is to Be Done? This was a work that might just as well have been written by the brilliant “Russian Jacobin,” Tkachev. In fact, one of Tkachev’s own proto-Bolshevik writings bears almost the same title (“What Is to Be Done Now?” published in Nabat, Nos. 3–5, 1879) as Lenin’s pamphlet, as does, of course, Chernyshevsky’s novel. For his dictatorship of the workers and peasants, Tkachev had even invented a Committee of Public Safety, anticipating Lenin’s Cheka, Stalin’s GPU, and the later KGB, which bore the initials KOB (Komissiya Obshchestvennoi bezopasnosti).

After Lenin’s death in 1924, the Leader’s obvious indebtedness to Tkachev confronted Soviet publicists with a ticklish problem as they set about fashioning the Stalinesque Lenin Cult. For one thing, it would not do for Lenin to be adumbrated by Tkachev, even though Russian historians (before 1924, that is) freely acknowledged the special Russian alloy of Tkachevism-Leninism. For another, Lenin’s Bolshevism was described (naturally) as a far superior revolutionary creed to any that preceded it. Lenin, after all, was an incomparable “genius.”

As a result, Tkachev’s writings were committed to the Orwellian Memory Hole. Or, as in the Brezhnev period, they were so emendated in a cretinized two-volume edition of Tkachev’s works (in whose introduction the Soviet editors also criticized me and my book on Tkachev—the first in English about him) as to be unrecognizable—either as essential Tkachevism or as examples of proto-Bolshevism foreshadowing Lenin’s ideology.

Albert L. Weeks

Sarasota, Florida

Martin Malia replies:

In commenting on Lenin’s role in 1917, both George Feifer and Albert Weeks offer arguments that are not without merit yet are nonetheless inconclusive.

Feifer makes the classic case that since Lenin, on his return to Russia in April 1917, was alone in his Party in advocating an immediate seizure of power, it follows that without him a Bolshevik coup could not have occurred “six months later.” While it is true that Lenin was briefly alone in the spring (and again was ahead of his Central Committee for a time in the fall), these facts can be properly evaluated only in the context of the rush of events in the eight months between February and October.

In April the first Provisional Government was still in power and it appeared that the results of February had been stabilized at a “bourgeois-democratic” level. In this context, advocating an immediate soviet-socialist seizure of power indeed seemed like madness. By June, however, the situation had so radicalized that the government itself was half socialist and all the Bolsheviks had fallen into line behind Lenin. Yet by July, the Party’s worker and soldier base had moved distinctly to his left, thus triggering an abortive insurrection that he had not foreseen and that almost destroyed his Party. In this fluid situation Lenin could only gamble his way to power, in the win-one, lose-one manner that Robert Service describes in Lenin: A Biography. The decisive factor in making this outcome possible thus was less Lenin’s foresight and leadership than a swift decent into anarchy that no party could master until the country hit bottom. And that is when Lenin had the luck to play his October card.

Albert Weeks emphasizes a more telling point in the Lenin debate, namely, his debt to the 1870s “Jacobin” Peter Tkachev. This maverick populist advocated a preventive revolution in Russia that would permit her to bypass capitalism and proceed directly to a socialism founded on the peasant commune. Since the peasants could not make such a revolution themselves, it would have to be engineered by a conspiracy of intellectuals governing thereafter as an enlightened dictatorship. In short, Tkachev to a degree anticipated the Bolshevik vanguard Party, and Lenin assiduously read his works in preparing What Is to Be Done? While all this is true, it is going too far to call Tkachev the “first Bolshevik,” as Weeks does in the title of his quite useful book. The idea of elite revolutionary conspiracy is hardly difficult to come by: it goes back to Auguste Blanqui in the 1840s and indeed to the ultra-Jacobin Gracchus Babeuf in 1796. More important still, Tkachev’s socialism remained peasant-agrarian not proletarian-industrial, a position he defended in a sharp polemic with Engels. And thirty years later Lenin’s emerging Bolshevism most decidedly incorporated whatever it owed to Tkachev’s politics into the Marx-Engels cult of progress through industrialization. Thus, I did not argue for “the limited degree of Lenin’s dependence on…Marx.” On the contrary, I emphasized the clear preponderance of Marxism in his mixed worldview.

On the Karl Marx monument still standing across the street from the Bolshoi Theater, there is inscribed a quote from Lenin that would be touching in its naiveté if it had not been so lethal in its consequences: “Marx’s teaching is all-powerful because it is true.” Lenin never said anything similar about Tkachev, or even about his idol Chernyshevsky. And it is this Marxist pseudo-rationalism that made the “October Revolution” truly revolutionary. For the real Bolshevik revolution was not the comic-opera “armed insurrection” of that month but the ensuing application of Marx’s “all-powerful” science to the building of industrial socialism on the ruins of peasant Russia.

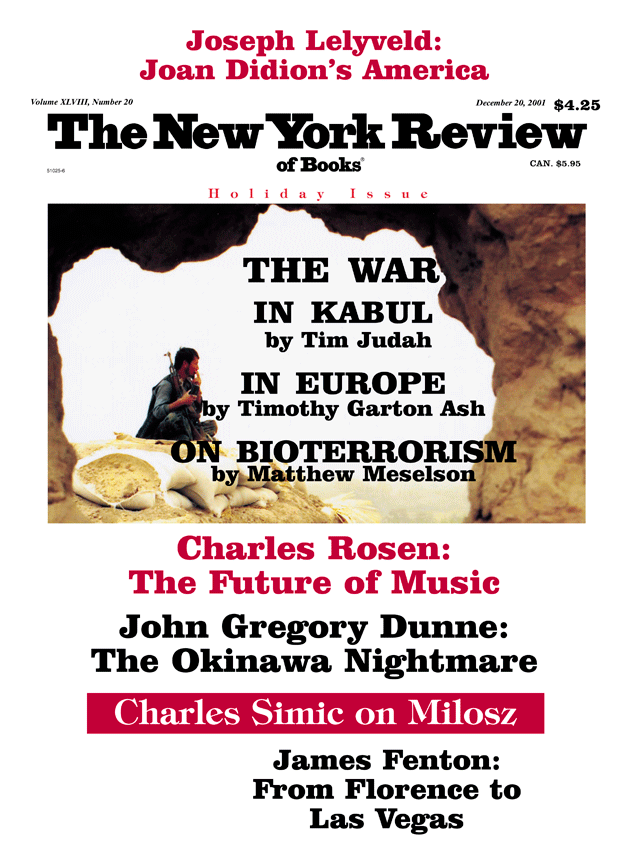

This Issue

December 20, 2001