To the Editors:

Tony Judt is quite right [“America and the War,” NYR, November 15] to say that condemnation of Israeli “settlements” cuts across national lines. There is a kind of universal rage against Israel. So universal and so intemperate is this rage that it tends to look a lot like a phenomenon we used to call by another name. Perhaps Mr. Judt can help us understand why this beleaguered little democracy, smaller than San Bernardino county, with or without its share of mistakes, should be the one subject of universal hatred?

Mr. Judt must know that Arab hatred and terror against Israel were unrelenting before 1967, even though there were no Jewish “settlements” on the West Bank. Why should Americans worry at all about the sensibilities of Muslims who are unwilling to live with Jews and Christians and Buddhists? And why should America change its foreign policy to accommodate such views? Wasn’t it Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, whom Mr. Judt despises, who expressed fear that we would appease terrorists at Israel’s expense?

Louise Weinberg

Professor of Law

University of Texas Law School

Austin, Texas

Tony Judt replies:

Many readers have written to me to express sentiments broadly akin to those in Professor Weinberg’s letter, so I am grateful for the opportunity to respond. Please note, though, that my article was about the problem of widespread international anti-Americanism. It did not directly address the Israel–Palestine question, which took up just two paragraphs.

There are three distinct issues here. First, is the crisis in Israel and the occupied territories the source of the modern Middle Eastern Question? No. Arab states have their own problems, many of their own making; Osama bin Laden is one of them. And American involvement in the region, like British before it, takes in Iran, Iraq, the Arabian peninsula, the Gulf, and North Africa, for reasons that reach back many decades and have more to do with securing oil supply than protecting the Jewish state.

Second, is the Israel–Palestine conflict a major contributor to modern anti-American feeling? I believe so. US loyalty to Israel is everywhere perceived as unwavering and uncritical. Accordingly, Israeli behavior directly affects the way people think about America. I did not reach this conclusion by burying myself in the editorial pages of al-Ahram: even the moderate newspapers of our strongest allies in Europe see things this way and admonish Washington for its refusal to rein in its friends in Israel. “So what?” Professor Weinberg might respond. If the Israelis are in the right we should keep backing them to the hilt, whatever foreigners think. But that raises my third issue.

Is Israel behaving irresponsibly? Many people think so, me included. That doesn’t make us anti-Semites. To condemn, for example, the settlements (why “settlements,” Professor Weinberg—they exist, don’t they?) is not the same thing as feeling “rage,” much less “hatred” against Israel. I don’t deny that commentary on Israel, and not only in the Middle East, is often driven by anti-Semitism. I have heard young Palestinian students at major American research universities earnestly discussing the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. I have seen well-known European academics couch their palpable distaste for Jews in respectable “anti-Zionist” rhetoric, and this tendency seems to be growing stronger. But what follows from this?

What follows, I think, is that we must stick to the facts. This ought to be an acceptable procedure—Israelis have long believed in creating “facts.” According to the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem, the second intifada that began in September 2000 has so far resulted in 172 Israeli civilian deaths, 89 of them in Israel proper. In the same period 592 Palestinian civilians have been killed. According to B’Tselem, 2,194 Israelis have been injured (soldiers and policemen included); according to the Red Crescent, injured Palestinians number nearly 17,000. (These numbers were announced as of December 16.)

It is the disproportions that are striking in these figures. Even if Israelis were somehow winning their “war against terrorism”—they are not—the scale of death and injury that they are inflicting on civilians is fast undermining their case. They are losing the moral high ground and, despite the appalling efforts of Palestinian suicide bombers, they have lost the war of image and propaganda. Sooner or later those conflicts merge and Israel’s tactics become a “fact” in themselves and an impediment to future solutions. More facts: the assassination of Rehavem Zeevi, the occasion for the latest Israeli exercise in collective punishment and extra-judicial execution (30 “suspects” killed during the recent occupation of six Palestinian towns) was what it was: murder. But Zeevi was by his own admission an enthusiastic practitioner of ethnic cleansing and cheerleader for a racially “pure” Greater Israel. Had he been born Serb or Hutu we in America might have a better understanding of why he inspired such hatred. His presence in the government of Israel said much about the current state of affairs there.

Advertisement

And then there is the prime minister. Ariel Sharon cynically marched up the Temple Mount on September 28, 2000, and in doing so helped to set off the present cycle of anger and death in the Middle East. His invasion of Lebanon twenty years ago was a military and moral disaster—not just for the Arab victims of Lebanese phalangists in Sabra and Shatila but for a generation of young Israeli soldiers, some of whom abandoned promising military careers rather than be associated with Sharon’s reckless adventures. He is the author of the 1992 “Sharon Plan,” under which Israel would annex 50 percent of the occupied territories and create eleven isolated “cantons” for the unenfranchised Palestinian residents. Ariel Sharon, like the settlements he so avidly endorses, is an impediment both to peace in the Middle East and to America’s battle with terrorists everywhere.

None of this implies that the Palestinian leaders are guiltless. Like his Israeli counterparts Yasser Arafat has taken almost every opportunity to miss a chance. In particular, the PLO threw away a real occasion to forge an alliance with the peace party in Israel. Palestinian rhetoric has often been inflammatory and deluded. And yes, this didn’t all start in 1967. I lived for a while in pre–Six Day War Israel under the shadow of Syrian guns on the Golan Heights and I recall the well-advertised Arab intention to “push the Jews into the sea.” But Professor Weinberg is wrong about one thing: before 1967 there was a lot less “terror” on both sides.

Before the present occupation, Palestinian Arabs often despised Israelis and denied Israel’s right to exist. But Israelis reciprocated in kind. I recollect being scolded by Mrs. Golda Meir in 1965 for using the word “Palestinian” in a public discussion: “There is no such thing as a ‘Palestinian,'” she admonished me. “There is no ‘Palestinian nation.’ There never will be.” Whether the future prime minister of Israel was right then is beside the point. She is wrong now—there surely is a Palestinian nation, another fact that Israel has helped create. It is behaving in ways sometimes reminiscent of other stateless peoples of the recent past—De Valera and the nationalists in Ireland before 1922, the Mau-Mau rebels in Kenya during the early 1950s, the Jews in Palestine before 1948. And like them it will sooner or later have its claim recognized and the terrorists Mr. Sharon would like to eradicate under the cloak of America’s revenge for September 11 will become, like Sharon’s own political mentors and sometime terrorists Itzhak Shamir and Menachem Begin, tomorrow’s political interlocutors. Some such outcome may even be imposed upon the two sides by a frustrated United States—as many Israelis and Palestinians tacitly concede and half hope.

My article raised hackles, I suppose, because of its timing—many people find it offensive even to discuss American or Israeli failings at such a moment. We are still burying Osama bin Laden’s victims and it is dismaying to acknowledge that there are people out there who like to see Americans die. But surely this is the moment for such a discussion, because violence against America and Americans is not about to stop and we need to understand it better if we are to fight back effectively. And if America and Israel really are in this together, as many of my correspondents insist, then that is all the more reason for asking why Israel too attracts such opprobrium. What is gained by placing Israel beyond censure and charging its critics with anti-Semitism? Is this to be the patriotic response to the crisis of our generation? That is the patriotism of the ostrich.

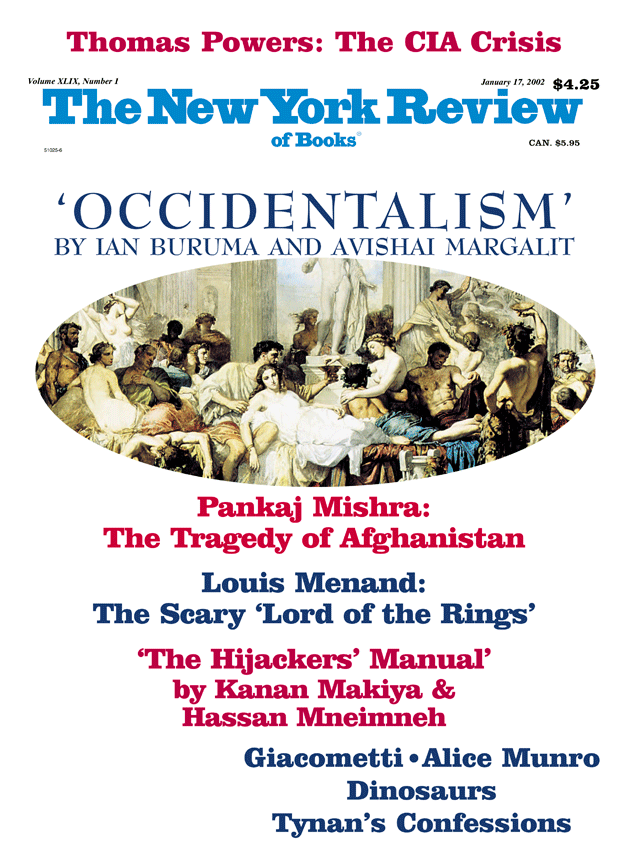

This Issue

January 17, 2002