1.

When one thinks of Scotland, the first thing that is apt to come to mind is the violence and turbulence that characterized it during most of its history. It is at once a saga of kings and desperate men—Duncan meanly slaughtered in the keep of his host and vassal Macbeth; Robert Bruce stabbing his rival the Red Comyn in the church at Dumfries; the Earl of Moray, Mary Stuart’s ambitious half-brother, shot from ambush in 1570 by a member of the Hamilton family in the streets of Linlithgow; the harassment of the Covenanters, groups of Presbyterians who took oaths to defend Scotland against English Anglicanism, in the notorious Killing Time of Charles II. It is also a tale of feckless gallantry and lost causes, in which victories like Bannockburn, where in 1314 a Scottish army led by Bruce defeated an English army twice its size, were always outnumbered by crushing setbacks like Flodden in 1513 and Culloden in 1746, in both of which the English inflicted devastating defeats.1

Arthur Herman, a former professor of history at Georgetown University, is not unaware of this melancholy record, but his attention is fixed on another story and another Scotland. He is intent on demonstrating how the inhabitants of a land that in 1700 was Europe’s poorest independent country created the basic ideals of modern life, which he equates with democracy, technology, and capitalism, and how starting in the eighteenth century those ideals transformed their own culture and society and the lands to which they traveled. Herman’s exuberant title, which will strike some readers as intended only to shock, is in fact meant quite seriously, and his book is a well-argued tribute to Scottish creative imagination and energy.

He starts by reminding us of modern Scotland’s debt to the Reformation. It had been the ambition of the sixteenth-century religious reformer John Knox to turn the Scots into God’s chosen people and Scotland into the new Jerusalem, and something of that spirit survived, in secular form, in the Scottish Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. Knox’s Presbyterian Church, moreover, had the most democratic system of church government in Europe, and the National Covenant of 1638, signed in protest against Charles I’s prayer book, was an early version of democracy in action.

Equally important was Knox’s call in 1560 for a national system of education, which was elaborated by a number of statutes in the course of the next century, notably the Scottish Parliament’s “Act for Setting Schools” in 1696. By the beginning of the eighteenth century Scotland had become Europe’s first literate society, with a male literacy rate 25 percent higher than that of England. Herman writes that “despite its relative poverty and small population, Scottish culture had a built-in bias toward reading, learning and education in general. In no other European country did education count for so much, or enjoy so broad a base.” This was notable in the case of Scotland’s universities, which were distinguished enough to draw students from across Protestant Europe. Because of their relatively low fees and the swelling tide of literacy, they became centers of popular education as well as of academic learning.

Scotland was well prepared, then, for the takeoff into the modern age before objective circumstances made that possible. The union with England in 1707 was not universally popular in Scotland and its economic advantages were slow in making themselves felt. The challenges of the last Stuarts to the English monarchy in 1715 and 1745 were formidable distractions, and it was not until after the defeat at Culloden in 1746 that cultural questions could supplant the preoccupation with politics. But by then the Scottish Enlightenment was free to begin its destined work, which was nothing less, Herman writes, than “a massive reordering of human knowledge,” the transformation “of every branch of learning—literature and the arts; the social sciences; biology, chemistry, geology, and the other physical and natural sciences—into a series of organized disciplines that could be taught and passed on to posterity.”

The great figures of the Enlightenment were teachers and university professors, clergymen and lawyers, all driven by a profound didactic purpose. The professor and divine Francis Hutcheson, the jurist Lord Kames, the philosopher David Hume, and the economist Adam Smith—to whom Herman gives pride of place among them—all broke with the austere fundamentalism of Knox’s Kirk (church) and the supposed immutability of divine providence. Instead, they placed human beings at the center of things, human beings seen as individuals with their private interests and frailties and limited rationality, and as the products of historical and social change.

Kames demonstrated that the development of human communities passed through four distinct phases and that the way people thought and acted was dependent upon whether they were occupied in hunting and fishing, or in pastoral and nomadic activities, or in agriculture, or in commerce. After that, the writing of history could never be the same again. And social analysis and indeed the science of government were profoundly different after Hume’s argument, as Herman puts it, that

Advertisement

self-interest is all there is. The overriding guiding force in all our actions is not our reason, or our sense of obligation toward others, or any innate moral sense—all these are simply formed out of habit and experience—but the most basic human passion of all, the desire for self-gratification. It is the one thing human beings have in common. It is also the necessary starting point of any system of morality, and of any system of government.

It was Adam Smith’s appreciation of this view, Herman writes, and the courage with which he confronted and analyzed the tension between what human beings ought to be and what they really are, rather than his role as high priest of modern capitalism, that made him one of the great modern thinkers.

The Scottish Enlightenment had two centers, Edinburgh and Glasgow. Unlike London and Paris, the only cities that could compete with it as an intellectual capital, Edinburgh’s cultural life was not dominated by state or aristocracy, but by its intellectuals and men of letters. It was a remarkably democratic society, in which there were no intellectual taboos and virtually all ideas could be debated freely. Herman writes that it was “like a gigantic think tank or artists colony, except that unlike most modern think tanks, it was not cut off from everyday life.”

Edinburgh was, even so, more artistic and literary and more intellectual in the abstract sense than Glasgow, which was truer to older attitudes, including a deep-seated Calvinist fundamentalism. Glasgow was also practical and innovative and intent upon how things were made and how to get things done. If Adam Smith and his friends were at home in the intellectual hurlyburly of Edinburgh, Glasgow was the natural habitat for James Watt, whose experiments with steam, Herman says, “created the work engine of the Industrial Revolution.” He adds:

…The version of technology we live with most closely resembles the one that Scots such as James Watt organized and perfected. It rests on certain basic principles that the Scottish Enlightenment enshrined: common sense, experience as our best source of knowledge, and arriving at scientific laws by testing general hypotheses through individual experiment and trial and error.

This gave capitalism its modern face and, among other things, created the classic industrial city. By 1801 Glasgow was Scotland’s biggest metropolis, with textiles, iron-working, and ship-building the driving forces of economic and demographic growth, and a population that was to increase from 77,000 to nearly 275,000 in the next forty years.

2.

How the fruits of the Enlightenment were carried beyond Scotland’s borders, Herman describes in the second half of his book. He begins with North America, whose Scottish ties go back to James I’s plans for a Scottish colony in Nova Scotia and were strengthened by the millions of Scots-Irish immigrants who arrived between then and the break with Britain in the eighteenth century. These were Scottish people who had settled in Ireland and became convinced they would do better in the New World.

Herman makes no claim that Scots won the American Revolution, but he insists that Scottish ideas had a crucial part in the formation and early development of the Republic. He makes much of the work of John Witherspoon, the minister from the town of Paisley, west of Glasgow, who became president of Princeton University in 1768. During his twenty-six-year tenure he numbered among his students a future president of the United States (Madison), a vice-president (Aaron Burr), six members of the Continental Congress, nine cabinet officers, twenty-one senators, thirty-nine congressmen, three Supreme Court justices, twelve governors, thirty-three state and federal court judges, and thirteen college presidents. Witherspoon exposed all of these to the ideas of the Scottish Enlightenment. James Madison in particular fell deeply under the influence of David Hume (not entirely to Witherspoon’s pleasure, since Hume was a self-confessed atheist), and Hume’s ideas are apparent in the tenth of the Federalist Papers, the key to the new constitution, in which Madison argued that countervailing public interests—federal, state, executive, legislative, economic—would guarantee private liberty.

Scots also had a central part in the reform of the British constitutional system at the beginning of the nineteenth century. The loss of America and the defeat at the hands of France and Spain had a demoralizing effect in England, complicated by political factionalism, mutiny in the navy, and a suspension of payments by the Bank of England. The country was saved from more of the same by a virtual invasion of Scottish ideas, writers, inventors, and politicians.

Advertisement

Chief among the forces for change was Dugald Stewart, professor of moral philosophy at the University of Edinburgh, who, Herman writes, influenced “the mind of Europe and the English-speaking world to a degree no Scotsman ever equalled before or since.” It was Stewart who gave wide circulation to the ideas of Adam Smith, making The Wealth of Nations into the classic source of modern economic theory. Even more important was the liberal optimism that informed his call for basic political reform in Britain. Undeterred by the fear induced by the violence of the French Revolution, he insisted that Britain—a land in which only one man in twenty had the vote—needed a revolution of its own, since “a modern society deserved a modern political system based on liberty, property and the rule of law.” The persistence with which Stewart hammered away at this theme prepared the way for the victory of the Reform Bill in 1832 in which two other Scots had important parts—Henry Brougham, an eloquent member of the board of the widely influential Edinburgh Review, and Thomas Babington Macaulay, the son of an abolitionist in Inverary. In the debate in the House of Commons that determined the fate of the reform, Macaulay’s was the most persuasive voice as he warned members:

The time is short. If this bill should be rejected, I pray to God that none of those who concur in rejecting it ever remember their votes with unavailing remorse, amidst the wreck of laws, the confusion of ranks, the spoliation of property, and the dissolution of social order.

The passage of the Reform Bill, which increased the British electorate by 50 percent and distributed seats in Parliament more fairly, prepared the way for the triumphs of the Victorian Age and the creation of the new British Empire, which eventually covered nearly one fifth of the earth’s surface and included a quarter of its population, an empire on which it was said that “the sun never sets.” A new book calls it “the Scottish Empire,”2 and if this is a bit far-fetched it is not greatly so, for certainly Scots were active in India, the Far East, the Pacific, and the later holdings in Africa and the Middle East. Benjamin Disraeli once said, “It has been my lot to have found myself in many distant lands. I have never been in one without finding a Scotchman who was not at the head of the poll.”

Critics of the Scots were apt to say that their frequent religiosity merely disguised a desire for gain and that they were driven by the principle “Keep the Sabbath and anything else you can lay your hands on.”3 This is unfair. The historian John Mackenzie has written:

Perhaps the most extraordinary contribution of the Scots to Empire was the fact that, from the eighteenth century on, they were slotted into international intellectual networks. They became the botanists and foresters of Empire. They had almost complete command of medical establishments until at least the middle of the nineteenth century, when the supremacy of the Scottish universities in this and other fields began to fade. They were the engineers and builders of imperialism, the creators of infrastructure and the suppliers and runners of railways. They largely carried all the new disciplines of tropical medicine, microbiology, entomology and veterinary science to a global stage from the late nineteenth century.4

Nor should this be surprising. While they sent a proportion of their population overseas that was matched only by the Irish, the Norwegians, and the southern Italians, the Scots alone had an advanced industrial and agricultural economy, and this was reflected in their diverse activities overseas.

During the nineteenth century Scotland was conspicuously free from the nationalism that marked other peoples like the Irish, the Italians, the Hungarians, the Greeks, and the inhabitants of Turkey’s Balkan provinces. The differences that had marked the first stages of the union with England had been ironed out, and the Scots had neither political nor economic reasons to seek independence. That changed, however, after World War I and the subsequent decline of the Empire, and the 1920s were years of industrial depression in the Lowlands and continued depopulation of the Highlands. The failure of both the Tories and the Labour Party to remedy this situation now made increasing numbers of Scots begin to think of home rule, and in 1928 a disgruntled group of these seceded from the Labour Party and formed their own national party, the SNP.

It was a long time before the new party was strong enough to make much difference in Scottish politics. It had been preceded by a strong wave of cultural nationalism inspired by the desire to end the miserable state into which Scottish literature had fallen since the days of Burns and Walter Scott. Writers such as Cunningham Graham, Eric Linklater, Neill Gunn, Compton Mackenzie, and most of all, Hugh MacDiarmid (Christopher Murray Grieve), who was to write the long poem A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, were intent on inspiring a literary renaissance that would restore the glories of the pre-Reformation poets Henrysoun, Dunbar, and Gawin Douglas. These intellectuals were drawn to the SNP when it appeared. Their political ideas, however, like MacDiarmid’s flirtation with fascism, his admiration of Lenin, and his “struggle…to show what Scotland micht hae hed insteid/ O this preposterous Presbyterian breed,”5 frightened away potential voters who wanted a party that was douce and canny, as a Glaswegian might say. They got such a party when some of the nationalist-minded intellectuals turned to other fields and were replaced by a leadership that one caustic critic said was “as exciting and imaginative as the Russian nomenklatura of the Brezhnev era.”6 The SNP then grew steadily and emerged as a mass political party in the late 1960s and early 1970s as a result of the continued failure of the Labour and Tory parties to offer a solution to Scotland’s sense of decline.

Today Scotland has a parliament of its own for the first time in nearly three hundred years, as well as a new Parliament House, a growing computer industry, and a prosperous service sector economy. Its sense of independence is enhanced by the fact that it is being wooed by the European Union to become a member. Not so long ago I received a clipping from an unidentified German paper showing three babes in swaddling clothes; one of them is female, and commenting, “In 2035 they will rule Europe: a Scottish finance minister, a French minister of culture, an Italian minister of nutrition.” Herman does not appear to be enthusiastic about an increasingly independent Scotland and seems to feel that Scotland under home rule may forget the great lessons of the Enlightenment. He writes:

The great insight of the Scottish school was that politics offers only limited solutions to life’s intractable problems; by surrendering her sovereignty the first time in 1707, Scotland gained more than she lost. She has to be careful that, in trying to regain that sovereignty, she does not reverse that process.

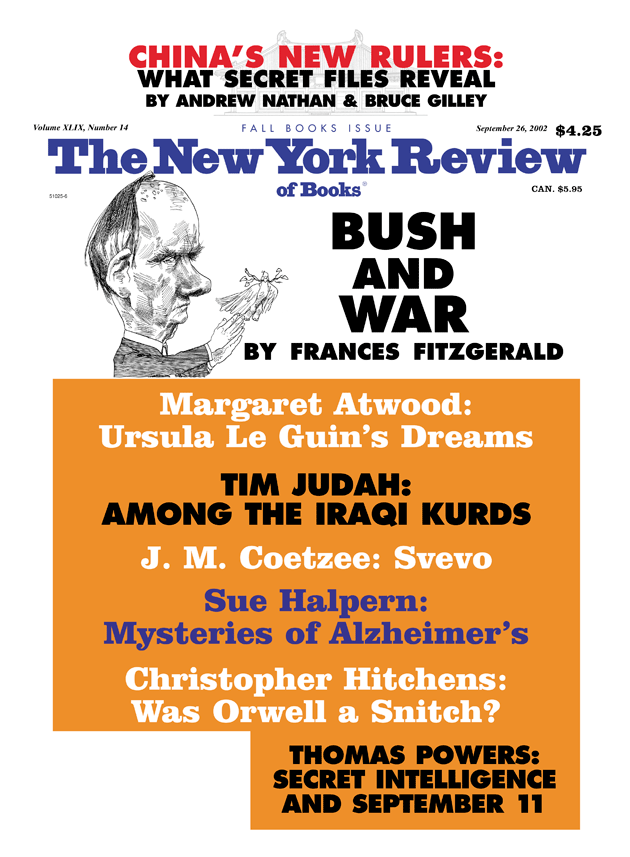

This Issue

September 26, 2002

-

1

These aspects of Scottish history are recounted in rich detail and lively prose in Magnus Magnusson, Scotland: The Story of a Nation (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2000). More comprehensive and scholarly but also more uneven, because it is a work by several hands, is The New Penguin History of Scotland from Earliest Times to the Present Day, edited by R.A. Houston and W.W.J. Knox (London: Allen Lane, Penguin, 2001). ↩

-

2

Michael Fry, The Scottish Empire (East Lothian: Tuckwell, and Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2001). ↩

-

3

Cited by John Mackenzie, “Hearts in the Highlands,” Times Literary Supplement, January 25, 2002, p. 11. ↩

-

4

Mackenzie, “Hearts in the Highlands,” p. 11. ↩

-

5

A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, ll. 736–738. ↩

-

6

Allan Massie in The Times Literary Supplement, May 20, 1994, p. 24. ↩