“I am a born Catholic,” Garry Wills reports. And in addition:

I have never stopped going to Mass, saying the rosary, studying the Gospels. I have never even considered leaving the church. I would lose my faith in God before losing my faith in it.

That reference to the rosary is impressive. It becomes even more pointed when Wills speaks of his “daily recitation of the creed when I say the rosary.” I, too, am a born Catholic, but my mother—a solid Catholic, but not ardent—seldom got me down on my knees, even on holy days, to say the rosary: it was a devotion nearly as rare as doing the Stations of the Cross. I have never practiced it. Wills’s home was evidently more devout. He was born in Atlanta on May 22, 1934, son of John and Mayno (Collins) Wills. John was not a Catholic, but he converted to Catholicism when the children had grown up, and meanwhile fulfilled his promise to have them reared as Catholics. Mayno was a vigorous Catholic of Irish extraction; she set the tone of domestic and religious custom. Wills’s parents were not well off, but they managed to send him to a local Catholic grade school, Saint Mary’s, and later to a Jesuit boarding school, Campion, in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. “Not a bad ghetto to grow up in,” Wills conceded in Bare Ruined Choirs: Doubt, Prophecy, and Radical Religion (1972).

Boarding school led to his entering a Jesuit seminary, Saint Stanislaus, in Florissant, Missouri, in 1951 with the intention of becoming a priest. That intention held good for about six years. When he left the seminary, it was “certainly with no weakening of my faith in God, Christianity, or the church.” He seems mainly to have got tired of the regimen by which novices who “wanted to serve Christ never even seriously studied Scripture, theology, or church history until they had been in the order for ten years, counting time out between philosophy and theology to teach in high school as a scholastic.” In 1959 he married and took up the vocation of familial life.

During his years in the seminary, Wills read a lot of devotional literature. Trained in Latin and Greek, he studied Greek drama and Saint Augustine, the saint becoming the major figure in his intellectual and spiritual life. Not Aquinas, strangely. When I was growing up in Northern Ireland, my teachers—the Christian Brothers—pointed me toward Aquinas, whose Summa theologiae was declared by Pope Leo XIII in 1879 to be the approved model for philosophic and theological discourse in the Catholic Church. I learned whatever I needed to know of the Church’s teaching by the easier method of reading a school book, Michael Sheehan’s Apologetics and Catholic Doctrine (1937). Out of school, I exacerbated my religious sense by reading François Mauriac’s God and Mammon and Georges Bernanos’s Diary of a Country Priest. G.K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy is the only devotional book Wills and I seem to have had in common. I enjoyed lurid books of edification; he reveled in Newman, Ruskin, Chesterton, but most of all Augustine: these remain his masters to this day. Wills has written political journalism, American history, and the history of the Catholic Church so abundantly that he has become his own authority, but he rarely writes an essay on religion without invoking the greater authority of Augustine, Newman, and Chesterton.

Two years ago, Wills published Papal Sin: Structures of Deceit, in which he argued that “the life of church authorities is lived within structures of multiple deceit.” In Bare Ruined Choirs he diagnosed “habits of falsehood grown up under cover of belief.” Such discrepancies are Wills’s abiding motifs. In Papal Sin he argued that the papacy, especially since the middle of the nineteenth century, has been rotten with duplicity, lies, and bad faith. He insists that the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin, declared in 1854, and the dogma of papal infallibility, declared in 1870, were mainly designed to gather all authority into the hands of the pope and his officers in the papal court, the Curia. Wills does not make much of the constraints and safeguards that limit papal infallibility—an encyclical is not enough for infallibility; the pronouncement must be made ex cathedra and the doctrines must be de fide definitae—or of the good faith of those 533 bishops who voted for it. “I am not infallible when I choose my snuff,” Pius IX said to Cesare Cantu.

The most resolute villains, by Wills’s account, have been Pius IX (1846– 1878), Pius XII (1939–1958), Paul VI (1963–1978), and the present pope John Paul II (1978–). These latter two have done everything they could to undermine the work of the Second Vatican Council of 1962–1965 and to destroy the council’s vision of the Church as “the people of God.” The deceits the several popes have practiced include opportunistic canonizations (Pius IX, Edith Stein, Maximilian Kolbe, and many more), and lies about the persecution of Jews, the Holocaust, apostolic succession, priestly celibacy, the ordination of women, contraception, and other issues. “In fact,” Wills claims, “the Vatican has attempted a coup, a takeover of the conciliar church it does not like.” John Paul’s apostolic constitution on Catholic universities, Ex Corde Ecclesiae, issued on August 15, 1990, and demanding that Catholic colleges and universities hire a majority of Catholic teachers, is only one of his many acts of folly, but folly is the least of papal sins.

Advertisement

Wills has come to his own conclusions on these matters, and he is convinced that he is right. He sees himself as a member of the Church’s loyal opposition, “constantly at hand to differ from the papacy and recall it to the Petrine charisms of unity, apostolicity, and love.” But he acknowledges that the Catholic Church has been highly successful “in preserving the great truths of the creed”:

It has remained trinitarian while other Christians drifted toward a vague unitarianism or vaguer pantheism. It still believes in original sin, and in its forgiveness by baptism. It preserves the truth of the Incarnation, the actual embodiment of the Lord—including belief in his fleshly resurrection, his reincarnation in his mystical body at the Eucharist, the eschatological vision of his judgment and of life everlasting.

The only question on which Wills is ready to say “I don’t know” is abortion, which he discussed in much the same terms in Under God: Religion and American Politics (1990). In Papal Sin he said of it:

Though the fetus may not be a person, it is human life, it has the potential to become a person. It is something that should not be lightly done away with or deprived of all respect. Women have the legal right to decide whether to have an abortion, but they should not take that as a dispensation from a moral decision-making task that goes deeper than the law. I cannot be certain when personhood begins, any more than Augustine was certain when the soul was infused. But against all those who tell us, with absolute assurance, when human life begins, we should entertain some of his knowledge of our limits. On the whole subject of the origins of life, he said, “When a thing obscure in itself defeats our capacity, and nothing in Scripture comes to our aid, it is not safe for humans to presume they can pronounce on it.”

The trouble is that other people are pronouncing on it while Garry Wills and Augustine are saying, “I don’t know.”

In Why I Am a Catholic—“an unintended sequel to my Papal Sin“—Wills returns to many of the issues he examined in that book and in Under God, Bare Ruined Choirs, and Confessions of a Conservative, published in 1979. He is as stringent as ever; he has not melted into tenderness. Sometimes he writes of the Church as if he expected it to be indistinguishable from God and were punishing it for gross failure in that respect. For a man so concerned with Catholicism, Wills seldom mentions God—He is acknowledged once or twice in Why I Am a Catholic—or speaks of the intimacy of his own religious experience. More often, he lets Augustine speak for him and makes quotation do the work of testimony. For whatever reason, he seems fixated on the Church, which is after all merely an institution, though a crucial one. Immensely gifted as Wills is in language, the vocabularies most congenial to him are social, political, and historical, not religious or theological.

The main difference between the new book and Papal Sin is that Wills has now brought forward a larger cast of popes, many of them presented as scoundrels, and that he has become more explicit, if not much more revelatory, about his religious beliefs. Chicanery in the papacy is not news, but you would imagine from reading Why I Am a Catholic that Wills’s motto is a sentence of Augustine’s—he quoted it in his biography of the saint: “The Church extends throughout the world, Rome excepted.” But Wills insists that he is not attacking the papacy or its defenders. “My own heroes,” he said in Papal Sin, “are the many truth tellers in Catholic ranks, preeminently Saint Augustine, Cardinal Newman, Lord Acton, and Pope John XXIII.”

These men became heroic when they interrogated the papacy or tried to change its direction. In 418 Augustine thwarted an attempt by Pope Zosimus to interfere in African Church affairs, and the following year, as Wills notes in Papal Sin, he “helped mobilize pressures that made the same Pope reverse himself—from exonerating the heretic Pelagius to condemning him.” Newman “got into his trouble with Roman authorities by writing that, during the Arian period, the Church at large preserved the faith when bishops and priests strayed into heresy.” Lord Acton opposed the definition of papal infallibility, and went to Rome in November 1869 to strengthen the resolve of the few bishops who might vote against it.

Advertisement

In 1959, when Pope John XXIII announced his intention of summoning the Second Vatican Council, he caused “a convulsive alteration of the whole religious landscape,” as Wills describes it in Why I Am a Catholic. John XXIII made serious mistakes, for example when he withdrew from the council’s discussion the question of contraceptives. But Paul VI and John Paul II, abetted by Cardinals Ottaviani and Ratzinger, Wills writes, tried to undo John XXIII’s great work of enlarging the sphere of open discussion in the Church, and they tried to impose upon the landscape a specious state of calm. In Bare Ruined Choirs Wills names Daniel Berrigan as an exemplar of “the prophetic church” whose task has always been to redeem “the kingly church.” The Christian message “is not authenticated from a throne.”

The principal theme of Why I Am a Catholic is not fully indicated by its title. The book might more accurately be called How and in What Sense I Am a Catholic. The main impulse of the book, as of Papal Sin, is to remove the aura of sacrosanctity that has surrounded the papacy:

The papacy did not come into existence at the same time as the church. In the words of John Henry Newman, “While Apostles were on earth, there was the display neither of Bishop nor Pope.” Peter was not a bishop in Rome. There were no bishops in Rome for at least a hundred years after the death of Christ. The very term “pope” (papa, daddy) was not reserved for the bishop of Rome until the fifth century—before then it was used of any bishop…. The so-called words of institution (“You are Cephas, and on this stone…”) did not actually institute the power, but predicted that it would arise at some time.

Wills maintains that apostolic succession does not mean “a linear descent of all bishops from the bishop of Rome.” In the second century it referred to “the joint testimony of the six outstanding communities of the early church,” those that claimed foundation from the apostolic period—Antioch, Philippi, Ephesus, Corinth, Thessalonica, and Rome.” Apostolic teaching was “whatever these churches agreed on,” and the Bible was whatever they said it was.

The Church, Wills writes, was “a community of communities, opposed to the private revelations and charismatic individualism of the Gnostics.” The Roman community emerged as “a symbol of unity and wholeness” mainly because of the reconciliation of Peter and Paul in Rome and the assumption that they were martyred there. But the Roman Church played only a small part in the articulation of the doctrines of the Trinity and the Incarnation; it “did not formulate the canon, establish the creed, or set up the episcopate.”

These arguments are suggestive, but not novel. They are available in W.H.C. Frend’s The Rise of Christianity, Klaus Schatz’s Papal Primacy: From Its Origins to the Present, and Bernhard Schimmelpfennig’s The Papacy, Wills’s main authorities. But the arguments don’t necessarily lead to the conclusion that Wills is recommending. Even if we agree that a claim for the primacy of Rome was not made until the Council of Chalcedon in 451, the papacy has enforced this primacy for many centuries, and has carried out what it regards as its teaching mission under that authority. Wills finds much of this work deplorable, insensitive, wrong-headed. He insists that he is not a biblical fundamentalist; he allows for the development of doctrine. But the allowance is grudging. If you compare Why I Am a Catholic with Newman’s An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, you find that Newman is much more generously disposed toward the teaching role of the Church than Wills is.

Newman wrote the Essay when he was still a Protestant—he became a Catholic on October 9, 1845—but he was already an advocate of the development of doctrine by the colloquy of laity and clerisy, and thought of the process as a “gradual” development of doctrine in response to felt necessities at particular times. He also made a distinction between implicit and explicit knowledge. The Apostles had the fullness of revealed knowledge, but some of it was latent or implicit: development was therefore justified. The papacy has the right to define traditions of belief and piety that have persisted among the faithful for centuries—as sensus fidelium—and to give those traditions a dogmatic form.

The doctrine of the Immaculate Conception—that Mary was “from the first moment of her conception, by a singular grace and privilege of God and by virtue of the merits of Jesus, preserved immune from all stain of original sin”—is not mentioned in the New Testament, but that is not an argument against its proclamation, if the faithful have felt it—or something like it—implicitly for many centuries. Pius IX may or may not have been wise in bringing forward Immaculate Conception at that particular moment, but that is a different question. Wills is probably right about the teaching actions of the papacy in the past two hundred years; but he cannot make the case chiefly by appeal to the early centuries in the history of Christianity. If he did, he would be a fundamentalist.

Wills has a second motive: to remove the aura of divinely given powers which he thinks surrounds the priesthood. He made much of this in Papal Sin. To understand the acerbity with which Wills speaks of the priesthood in Why I Am a Catholic, one must read his chapter called “Priestly Caste” in Papal Sin. His attitude may to some extent be explained by the disappointment of his years in the seminary. Some of his best friends are priests, but he remains sarcastic about the priesthood, as in this sentence about the teaching priests in his seminary:

The keepers of the mysteries were led to think of themselves as an elite group of “initiates,” who dispensed knowledge on their own authority, not on the basis of convincing explanation.

That seems to me a venial sin on the part of priests. Much of the little knowledge I have is attributable to authority and trust—accepted from writers, doctors, teachers, priests, meteorologists, historians, lawyers, journalists—rather than to convincing explanation in every case. But Wills’s attitude toward the priesthood seems to be provoked by what he interprets as the role of the priest in the Eucharist.

Since the Council of Trent (1545– 1563) Catholics have been taught that in the sacrament of the Eucharist the body and blood, soul and divinity, of Jesus, “the whole Christ is truly, really, and substantially contained.” In the standard teaching, the presence of Christ is called real because “it is presence in the fullest sense: that is to say: it is a substantial presence by which Christ, God and man, makes himself wholly and entirely present.” By the consecration of bread and wine in the Eucharist “there takes place a change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of Christ our Lord and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood.”

This change is called Transubstantiation. Wills, so far as I know, accepts this belief, though he rarely mentions it. But in Papal Sin he accuses Athanasius of Alexandria of promoting “the idea of the priest as a person whose power resides in his eucharistic consecration.” Wills makes fun of the priest for whom he was an altar boy in private Mass, “who was either so scrupulous or so pious that when he came to the purported words of consecration he sounded out each consonant and vowel separately, as if making sure the magic formula was given all its force: Hoc est e-nim cor-pus me-um.” Why not? I would regard it as a scandal if the priest scrambled the words, even in a private Mass. “Purported”? Unless Wills means that Jesus didn’t speak Latin, the implication, for a Catholic, is mischievous. So is the reference to “magic.” Magic is not entailed: miracle is.

Wills disapproves of this emphasis because “it separates the priest from the community whose joint meal was the original condition of the Eucharist.” The power of the priest in the Eucharist, he claims, “was the source of awe he could elicit from the faithful.” As if eliciting awe were the priest’s first concern. Wills seems to resent the Church’s emphasis on Transubstantiation and its mystery. He is determined to interpret the Mass as a social act, in which the power of consecration does not belong to the priest but to “the Holy Spirit” in its relation to the faithful community:

As Bernard Häring says: “It is not we priests who consecrate, such that what was bread becomes the presence of Christ. This mystery takes place on the occasion of epikleåøsis by the power of the Holy Spirit.” Even if one does not accept this interpretation of the sacrament, it is clear that the Spirit’s presence in the community is what consecrates…. Since the Spirit consecrates within the community, if one person presides at the Eucharist, it is simply as the community’s representative, not as Christ’s…. It is more the faithful who become the body and blood of Christ than bread and wine do.

Wills thinks that many features of the Mass as it was celebrated before the Second Vatican Council were intended to enhance the mystery of the consecrating power of the priest and to bewilder the ignorant laity: the Latin language, the priest turning his back on the congregation, the communion rail separating the people from the altar, the laity never touching the sacred Host except to consume it. Wills has claimed that the unwillingness of Catholic parents, until recently, “to believe allegations against priests” is related to “the ethos of Catholicism from the mid-twentieth century, when the priest was an especially holy figure” and to “the minatory aura of the Church.”* These find their ultimate explanation, he thinks, in the power attributed to the priest in the Eucharist. Again he appeals to Augustine:

Almost three centuries later [than Ignatius of Antioch], Augustine was still talking of the faithful as the stuff that is transformed by the Eucharist. He never mentions (any more than the New Testament did, or Ignatius did) the power of the priest to consecrate. He says it is the faithful recipients who make the body of Christ present by becoming it. Over and over he places the validity of the sacrament in the recipient’s unity with God and each other, not in any preceding words or magic of the priest.

When Wills speaks of priests in the Eucharist, he makes them seem like illusionists, magicians, or witch doctors. I respect his social and communal emphasis, though I don’t see how the temporary transformation which he attributes to going to Mass, as he describes it, differs from the experience of a crowd at a rock concert or a football match. I was never a seminarian or even a pupil at a Jesuit school. But I do not find priests in the Eucharist practicing witchcraft or trying to elicit from me any awe in their personal favor. They are ministers in a sacrament; their acts are impersonal and vicarious. I think I understand why Wills wants to domesticate the mystery of the Eucharist, though I don’t share his desire. He wants to remove the miracle of Transubstantiation, and to replace it by the rapture of social union. Pascal has something to say about that:

Just as Christ remained unknown among men, so too his truth is in no way outwardly distinguished from other generally expressed opinions. So, too, the Eucharist in the midst of ordinary bread.

Wills seems to want to be a pre-Tridentine Catholic, i.e., one who believes that the Council of Trent introduced severities of doctrine and practice that were unnecessary and improper. He would apparently confine his faith to the articles of the Apostles’ Creed, where Transubstantiation is not mentioned.

In the last part of Why I Am a Catholic Wills writes out the Apostles’ Creed and offers his sense of every article of it. It speaks what he believes. The creed is so called because it is a summary of the faith of Peter and the other Apostles, “supposedly formulated by the Twelve before they left Jerusalem, each on a separate mission to his part of the world.” Wills prefaces his explication with a passage from one of Newman’s sermons:

Not even the Catholic reasonings and conclusions as contained in Confessions [creeds] and most thoroughly received by us are worthy of the Divine Verities which they represent; but are the truth only in as full a measure as our minds can admit it; the truth as far as they go, and under the conditions of thought which human feebleness imposes.

Wills does not elucidate every word of the creed, but he writes an appropriate commentary as if in the margins of each article. So far as they go, the commentaries are excellent, and are all the better for the help Wills has accepted from Augustine and Chesterton in formulating them. I cannot find fault with them, since they represent some part of my own belief. But readers outside the Catholic fold are bound to find several of Wills’s words and phrases obscure. Starting with “God, ” as in “the personal nature of creation as God’s act.” Then going on to “person” as in “the three persons of the Trinity.” And to “the Holy Spirit,” interpreted by Wills as “the animating principle of the body of Christ” and later, surely with poetic license, as “the feminine aspect of God.” Here Wills quotes lines from Hopkins’s “God’s Grandeur”:

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

When he comes to “born of the Virgin Mary,” Wills writes some of his most eloquent sentences:

When I say the five glorious mysteries of the rosary, the fourth is Mary’s bodily assumption into heaven—the only dogma to be infallibly defined since Vatican I set the rules for infallible pronouncements…. [But] Vatican I’s grant of infallibility has proved a nugatory power. Mary was always an exemplar of the resurrection that all the faithful look forward to. The definition neither added to nor detracted from that role.

Indeed, the entire last section of Why I Am a Catholic is among Wills’s most memorable writings.

So we know what he believes and what his being a Catholic entails. What more does he discuss? He wants Catholics to take up their mission in the Church where John XXIII left it and go further in his wisest direction. The Church should be in truth “the people of God,” it should not be hierarchical, with power concentrated in the hands of the pope and his officers and descending sluggishly through cardinals, bishops, and priests to those with no voice at all, the laity. Newman, as Wills reminds us, “made the seat of social identity for the Church the whole body of the faithful, not just the hierarchy or the priesthood.” Experienced continuity with the Gospel “rests in the Christian community at large, not in a private revelation to Popes or the teaching sector (Magisterium) of the Church.”

“Continuity within development” is one of Wills’s favorite phrases when the question of Church and doctrine arises. But he likes even more a phrase he used in his book Confessions of a Conservative: “brotherhood without fatherhood,” meaning “mutual deference rather than submission to one patriarchal source of authority.” I suppose this means: make the Catholic Church what it has never been, a democratic institution. Or in another version: join the prophetic church and redeem its false, kingly brother. What bearing this redemption would have on the world or even on, say, contemporary American foreign policy, Wills does not explain. Perhaps he will, in a book soon to come.

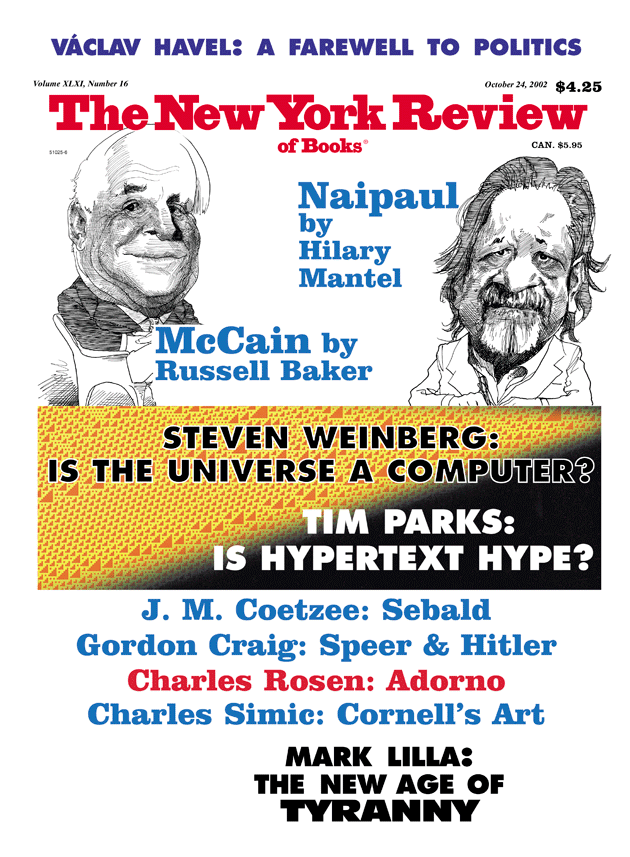

This Issue

October 24, 2002

-

*

“Scandal,” The New York Review, May 23, 2002, and “Priests and Boys,” The New York Review, June 13, 2002. ↩