When Diane Waldman selected the pieces for the 1967 exhibition of Joseph Cornell’s work at the Guggenheim Museum five years before his death, and wrote for the catalog what was one of the first extensive critical articles on the artist, he was practically unknown. Even the far more wide-ranging retrospective exhibition at MOMA in 1980 and the fine essays and more than three hundred illustrations in the catalog did not make his name much more familiar to the wider public. There was a reason for that. Avant-garde movements, one supposedly more radical than the other, came and went in the years in question, trumpeting other names and competing for attention. If the works themselves and the aesthetic claims made for them were often laughable, it did not seem to matter since they sold for astonishing sums of money.

Then all that gradually changed in the 1990s. Everything that made Cornell a marginal figure—his distance from current fashions and the oddness of his art, with its small-size box constructions in which a variety of inconsequential found objects are assembled—began to attract interest. During the last decade we have had a biography of Cornell, a book of selected diaries, letters, and files, a study of his interest in cinema, a volume on his vision of spiritual order, and several other equally interesting monographs, catalog texts, and isolated essays. Cornell brings out the best in critics and literary historians. He charms them by the way he combines in himself complete ordinariness with high sophistication. They know that even after every aspect of his career and art has been carefully documented, he will remain an enigma. That’s why books about him keep being written. When even the most persuasive speculations fail to fully account for the originality of the work, one has no choice but to look again and again.

Long before the Cubists tore up newspaper headlines to make collages and Marcel Duchamp displayed a store-bought snow shovel as a work of art, there was Walt Whitman’s poetry with its frequent catalogs of seemingly random images. A “kaleidoscope divine,” a “bequeather of poems” is what he called the city of New York and its motley crowds. Street life in all its bustle and variety is one of the great discoveries of modern art and literature. Whitman and Baudelaire were intense original observers of the city around them and so was Cornell in his own special way. I don’t believe that he would have become an artist had he spent his life cooped up in some small town in Maine or Kansas. He couldn’t draw, paint, or sculpt, so what would he have done with himself there? In New York, he did what the city already does anyway: make impromptu assemblages out of many different kinds of realities. An image hunter is how he described himself. He had no clear idea what he was looking for or what he would find. For years, before he made any art, he roamed the streets in a state of expectancy. In that respect, he was not unlike thousands of other unknowns, then and now, who in certain inspired moments experience their own solitude and unhappiness as a kind of poetry.

Cornell said that when he studied astronomy in school, he was frightened by the concept of infinity. Imaginary travels were his lifelong occupation, but he made sure that he slept in his own bed every night. Except for the four years he spent as a student at the Phillips Academy in Massachusetts, he never set foot outside the New York City area. He was born in 1903 in Nyack to parents who were both descendants of old Dutch families in the region. His mother’s grandfather owned schooners and prize-winning yachts. Cornell had two younger sisters, and a brother who suffered from cerebral palsy. His parents were ostensibly a happy, cheerful couple. They loved acting and performed at an amateur arts club. His mother, who had been a classmate of Edward Hopper, played the piano and his father sang. His father made his living as a salesman and then eventually as a textile designer for a manufacturer of fine woolen goods. Cornell was thirteen years old when his father died of leukemia, leaving behind enormous debts. The family had to move from the large Victorian house they occupied to smaller houses in Queens and then in 1929 his mother bought the house on Utopia Parkway where she and her two sons lived for the rest of their lives.

Cornell left school in 1921 and, following his father’s example, went to work as a textile salesman. He never married. Women both obsessed and terrified him. A true loner, shy, self-absorbed, feeding himself mostly on cakes and ice tea, he nonetheless immersed himself in the culture of the city, taking in opera, classical music, theater, and ballet, and regularly visiting art galleries. He was also by now a compulsive collector. Walter Benjamin in his encyclopedic, unfinished study of Paris arcades has a number of interesting things to say about that compulsion:

Advertisement

Perhaps the most deeply hidden motive of the person who collects can be described this way: he takes up the struggle against dispersion. Right from the start, the great collector is struck by the confusion, by the scatter, in which the things of the world are found. …The collector…brings together what belongs together…by keeping in mind their affinities….1

In every collector hides an allegorist and in every allegorist a collector, Benjamin goes on to say. For a true collector, the collection is never complete for as soon as he discovers an item missing his collection seems to him reduced to patchwork. On the other hand, there is the allegorist for whom the universe is already fragmented and for whom individual objects are words in a secret dictionary that come to make their meanings known in certain heightened states of perception. Which type of collector was Cornell? He believed in chance, in lucky finds, so it’s not easy to classify him. According to Diane Waldman’s new book, Joseph Cornell: Master of Dreams, here is where he poked around:

He frequented The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Morgan Library, the Museum of Natural History, and the Hayden Planetarium. He made photostats of his favorite images from the Public Library Pictures Collection and the Bettman Archives. He scoured the Asian shops between 25th and 32nd Streets, where he found Japanese prints and the first small boxes for his objects, and he frequented a taxidermy shop in the Village and a pet store near Radio City Music Hall. Many of his favorite objects came from Woolworth’s, the five-and-dime store from which he purchased stamps, wine glasses, marbles, gold-colored bracelets, and painted wooden birds. He hunted down clay pipes, specifically those that were Dutch in origin. What began as a pastime became an obsession that fed his everyday life and his creative imagination….

Some of the other places he haunted were Washington Square Park, Brentano’s Bookstore, John Wanamaker stores, the Old Print Shop on Lexington Avenue, Renwick C. Hurry’s Antiques, the F.A.O. Schwartz toy store, Bigelow’s Pharmacy on Sixth Avenue in the Village, the Fourth Avenue used book stores, and the Christian Science Reading Room on Macdougal Street. He had converted to Christian Science at the age of twenty-two and remained a lifelong member of the church, attending meetings several times each week. Waldman argues convincingly that Christian Science provided him with a metaphysical frame for understanding Surrealism. Both believed that spirit is the foundation of matter and that knowledge lies within us. Improbable as this may sound, in the work of Joseph Cornell, Mary Baker Eddy meets André Breton. Had she read this passage from Breton’s Second Surrealist Manifesto (1929), I suspect, she would have agreed:

Everything leads us to believe that there is a certain point in the spirit from which life and death, real and imaginary, past and future, communicable and incommunicable are no longer perceived as contradictories. It would be vain to look for any other motivation in surrealist activity than the hope of determining this point.2

In his years of roving around the city, Cornell assembled a vast collection of what he called ephemera and what most of us would regard by and large as trivia. If he had not eventually figured how to make original twentieth-century art out of his stashes of old movie magazines, moldy engravings, yellowed postcards, maps, guidebooks, film strips, photographs of ballet dancers, and hundreds of other items stored in shoe boxes and scrapbooks in his basement, they would have ended up at a dump or in a flea market. Creative filing, he called it. Each file was an arcane compilation, the result of a complex chain of private associations. He had no other use for them in mind; but unknown to him at the time, his archives supplied him with the material and even more importantly with the technique for how to go about making art.

The story of how he became an artist is by now familiar and Waldman tells it succinctly and well. In November 1931, Cornell strayed into the Julian Levy Gallery at 602 Madison Avenue and watched Levy himself unpack Surrealist artworks intended for an exhibition. The gallery had recently opened and was soon to become the place where American artists could keep abreast of the European avant-garde. The art he saw that day, despite its unfamiliarity and oddity, gave him an idea of what to do with the stuff he’d been piling up in his basement. As his diaries show, Cornell may not have paid much attention to theoretical controversies, but he certainly knew how to look at art.

Advertisement

Shortly after seeing some of Max Ernst’s collages in which nineteenth-century illustrations from scientific, commercial, and popular magazine stories were cut up and combined into startling new images, he returned to the gallery with his first modest efforts. Levy made them part of a group show, Surréalisme, in January 1932. Levy also asked Cornell to design the cover for the catalog. The show included paintings and photographs by Dalí, Ernst, Picasso, Man Ray, Eugène Atget, László Moholy-Nagy, and Marcel Duchamp’s ready-made Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy? (1921), which consisted of a painted birdcage filled with marble cubes, wood, cuttlebone, and a thermometer. Cornell’s own contribution was a glass bell with a mannequin’s hand inside it holding a collage of a rose. Glass bells became popular in the Victorian period for displaying clocks, model ships, dried flowers, stuffed birds, and other valuables.

What he quickly learned from the Surrealists is that just about anything from a medicine chest or a pill box to a coin-operated contraption with a peephole in a penny arcade can be used as a setting for a work of art. Perhaps getting down on all fours and peeking into some dark corner under one’s bed is a good introduction to his shadow boxes. If a small hoard of lost items happens to be there—so much the better. Who hasn’t made believe in one’s own childhood that a small pebble that fell out of a shoe was an animal or a human being? Cornell’s constructions recall for us a time when we had a few imaginary friends and some favorite broken toy as secret playmates. That’s not the whole story of their appeal, of course, but that’s surely where it all begins.

Here—just so the reader knows what is involved in such constructions—is a shortened inventory of the items Monique Beudert found in his early masterpiece L’Égypte de Mlle Cléo de Mérode, his homage to the famous courtesan and ballerina of the 1890s which Cornell made in 1940:

Hinged casket; lid lined with marbleized paper, cutouts of printed phrases L’EGYPTE/de Mlle de Cléo Mérode/COURS ELEMENTAIRE/ D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE and picture of seated Egyptian female; box divided by sheet of glass into 2 horizontal levels. Contents of sealed lower level: loose red sand, doll’s forearm, wood ball, German coin, several glass and mirror fragments. Contents of upper level: 12 removable cork-stopped bottles (tops of corks covered with marbleized paper, most bottles labeled with cutout printed words), in 4 rows of 3 set in holes in sheet of wood covered with marbleized paper; strips of glass forming 2 rows of glass-covered compartments (3 each) at sides of bottles. Contents of each bottle (and labels): (1) cutout sphinx head, loose red sand; (2) numerous short yellow filaments with glitter adhered to one end…; (3) 2 intertwined paper spirals…; (4) cutout of woman’s head…; (5) cutout of camels and men, loose yellow sand, ball…; (6) pearl beads…; (7) glass tube with bulge in center, residue of dried green liquid…; (8) crumpled tulle, rhinestones, pearl beads, sequins, metal chain, metal, and glass fragments…; (9) red paint, shell or bone fragments…; (10) threaded needle pierced through red wood disc…; (11) bone and frosted-glass fragments…; (12) blue celluloid liner, clear glass crystals….3

If this was not already crazy enough, the individual bottles have labels with names like Le Mille et une Nuits, Temps fabuleux, Cleopatra’s Needle to make our imagination run wild. By what inner logic, chain of chance associations, or esoteric principles were all these things arranged here, one wonders? Cornell learned from Duchamp and the Surrealists about the poetic qualities an object acquires once it is removed from its habitual context and given a new name calling into question its identity. Only what is useless is beautiful. Objects are more interesting when we overlook their function and their latent symbolism and admire them solely for their appearance. Cornell had an exquisite sense of design and he put things next to each other in his boxes as much for their private, emblematic qualities as for the visual pleasure they gave him. He wanted to create a new visual experience without worrying very much what it all means in the end. In other words, aesthetic considerations for him prevailed over specific meaning, but to what degree we cannot be sure. Many of his constructions leave us uncertain whether to regard them as allegories or as abstract art.

Waldman’s study proceeds chronologically from Cornell’s earliest assemblages to his box constructions of the 1940s and 1950s, his homages to Romantic ballet and portraits of women, and finally to his late collages. There are separate chapters on the Medici series and his Aviary boxes, and one devoted to his Observatories, Night Skies, and Hotels. The illustrations are good and plentiful. Although her book covers mostly familiar ground, as an introduction to the artist and his work, it is first rate. Any study of Cornell is an effort to trace and understand the many influences on him. The art, literature, films, and books he loved come in for close scrutiny and the results of that inquiry are at first surprising and then seem inevitable. For example, Waldman discusses the influence of Vermeer on the Medici boxes:

Cornell understood the fundamentals of Vermeer’s art, especially the rigor with which the Dutch master structured his images, his interest in perspective, color, and light, and his painstaking attention to detail. Vermeer created domestic interiors in which the everyday and the commonplace take on the aura of the transcendental and the sublime.

For his Medici boxes, Cornell used photostats of Renaissance paintings of young boys and girls. In Untitled (Pinturiccio Boy) (1942–1952), as in other works in the series, Waldman writes,

space is fragmented into small rectangles and bisected by black lines crossing the surface. The inner sides and the bottom of the box are covered with Baedeker maps of Venice and augmented by the ubiquitous spiral and two freestanding “toy blocks.”

Like its companion, Untitled (Medici Princess) (1948), “these boxes are notable for their tinted glass: brown for the young boy, blue for the young girl. The colors contribute to the tone of solemnity and purity.” In his diaries, Cornell records seeing faces in poorly lit subway stations, little tableaus that, he writes, could have been magical on film. He describes what he saw as a kind of purgatorio climate of light. The ever-maddening elusiveness of such experiences is a constant worry for Cornell, for they were something that no words could hold. “Expressivity of eyes music of language,” he writes elsewhere in his diaries.4

Then there is Mondrian and his grid paintings. Cornell moved in the same circles as the Dutch painter and he not only knew his work but was also aware of his interest in theosophy. Waldman makes the point that Mondrian’s paintings were influenced by the buildings he saw in Manhattan. Not only entire buildings, I would surmise, but particular windows too. Cornell, in a diary entry for October 17, 1956, confesses that the original inspiration for his Aviary series was “the magic simplicity of store windows.” Waldman observes that his boxes in the late 1940s begin to have an abstract, architectonic, gridlike appearance. Indeed, they make one think of vacated office buildings with their whitewashed interiors, bare floors, and rows of curtainless windows. It’s a poetry of absences, of spacious, empty spaces swept clean except for some odd object left behind. “Great sense of everything white—but more than just physical ambience—a sense of illumination,” Cornell writes.5 “N.Y. City Metaphysics” is the name he gives to such almost mystical experiences.

For anyone familiar with Cornell’s shadow boxes, it is hard not to think of them now and then as one walks the streets of New York. “My work was a natural outcome of love for the city,” he said to Jack Kroll of Newsweek magazine.6 He also insisted that whatever he did sprang from real experiences, and I have no reason to doubt him. Along with this down-to-earth side, he saw himself as an explorer of spiritual mysteries. Both Duchamp and Mondrian thought of him as a poet. They did not say what kind, but I suspect they had in mind someone like Mallarmé, another Symbolist master famous for the ambiguity of his verses. Cornell did not regard any of his works as ever finished and no poet does either. Their meaning was as unresolved for him as it is for us. It is because what we see with our eyes can be a poem, too. The intersection I happen to be hurrying across today with its panorama of white clouds and dark buildings on a late summer dusk is unfathomable in its beauty. Cornell once had a vision of Fanny Cerrito, the famous dancer of the Romantic era, in the windows of the Manhattan Storage and Warehouse Company on West 52nd Street. Undoubtedly, the reason we love cities is that they set the imagination free. Like a shadow discreetly following a lone pedestrian as he makes his slow way down a long block, we are drawn to Cornell’s art because it holds us spellbound while continuing to keep its secret. Diane Waldman’s book happily never loses sight of that.

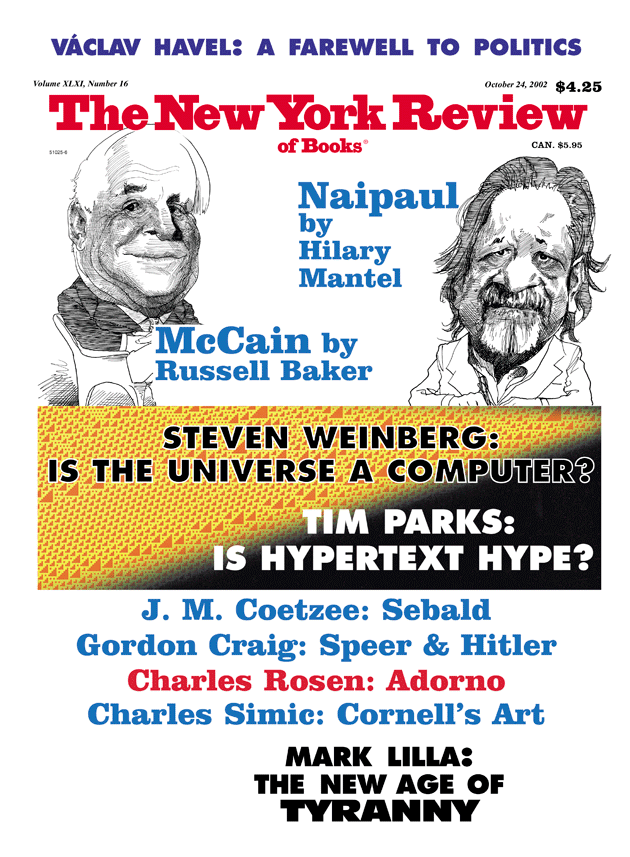

This Issue

October 24, 2002

-

1

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, edited by Rolf Tiedemann and translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLoughlin (Belknap Press/ Harvard University Press, 1999), p. 211. ↩

-

2

Michel Carrouges, André Breton and the Basic Concepts of Surrealism (University of Alabama Press, 1974), p. 11. ↩

-

3

Joseph Cornell, edited by Kynaston McShine (Museum of Modern Art, 1980), p. 282. ↩

-

4

Joseph Cornell’s Theater of the Mind: Selected Diaries, Letters, and Files, edited by Mary Ann Caws (Thames and Hudson, 1993), p. 201. ↩

-

5

Joseph Cornell’s Theater of the Mind, pp. 220, 303. ↩

-

6

“Paradise Regained,” Newsweek, June 5, 1967. ↩