1.

The Truce of 1968

George Weigel, former president and now senior fellow of the Ethics and Public Policy Center, has written a major and much-respected biography of Pope John Paul II. He knows and is known by important Vatican figures, and is in full sympathy with the Pope’s thoughts and actions. Without being an official spokesman, therefore, he may in some measure reflect Vatican thinking on current scandals in the Catholic Church. His new book is, in fact, often mentioned by Governor Frank Keating of Oklahoma, who leads the review board for evaluating the American bishops’ observance of their Charter of the Protection of Children.1

Weigel repeats what has become a conservative mantra within the Church—that the current situation is not a crisis of sex, or authority, or bad administration, but “a crisis of fidelity.” By that he and his allies mean that it is caused by a lack of belief in “the full teaching” of the Church, which prevents “full communion with the Church.” What is the connection between this lack and pedophile priests or complicit bishops? This: Refusing to believe in the full teaching deadens the conscience, and when your conscience is deadened you are likely to do anything, such as raping little boys. Speaking of seminarians “in the quarter-century following the Second Vatican Council,” Weigel writes:

They fell out of full communion with the Church, whether the issue at hand was contraception, abortion, homosexuality, or the possible ordination of women to the priesthood. If a priest is sincerely convinced that the Church is teaching falsely on these or other matters, or if he is simply lazy and absorbs the culture of dissent by osmosis, his conscience is deadened. And having allowed his conscience to become moribund on these questions, he is more likely to quiet, and perhaps finally kill, his conscience on matters relating to his own behavior, including his sexual behavior.

There you have it: believe that women can be ordained, and you are on the slippery slope gliding down toward pedophilia. On which there are three things to say. First: Since a majority of Catholics in America now say they favor women’s ordination, and since a deadened conscience has consequences for everyone, not only for priests, then a majority of Catholics must be drifting toward acts of pedophilia, or something equally immoral. Second: The most flagrant pedophiles so far convicted were not trained in “the quarter-century following the second Vatican Council,” so their lack of “full communion” cannot be traced to that period. For all we know, the serial molester of boys in Boston, Father Geoghan, who was trained well before Vatican II, was in full accord with the Pope’s bans on contraception, women’s ordination, and so forth—suggesting, third: that right doctrine does not ensure right conduct. It is not, necessarily, a lust-suppressant. Weigel repeats several times that “ideas have consequences.” True enough; but so do passions, interest, and ambition, among other things.

If Weigel is simplistic about the connection between thought and conduct in the individual, he is even more simplistic on causation in social dynamics. He dates much of the breakdown in “fidelity” to a pivotal event, what he calls “the Truce of 1968.” When Pope Paul VI issued his encyclical Humanae Vitae, repeating Pius XI’s 1930 condemnation of contraceptives, nineteen priests in Washington, D.C., publicly disagreed with it. Their cardinal, Patrick O’Boyle, threatened them with suspension or other punishment. At this point, Pope Paul, who is as much the villain of Weigel’s book as Pope John Paul is its hero, lost his nerve, according to Weigel, and made a fatal compromise: “Pope Paul VI wanted the ‘Washington Case’ settled without a public retraction from the dissidents, because the Pope feared that insisting on such a retraction would lead to schism.” And thus was born, in Weigel’s eyes, a culture of dissent:

The tacit vindication of the culture of dissent during the Humanae Vitae controversy taught two generations of Catholics that virtually everything in the Church was questionable: doctrine, morals, the priesthood, the episcopate, the lot. More than a few Catholics decided that a Church prepared to tolerate overt rejection of a solemn act of papal teaching authority could not be that serious about what it was teaching on this or other matters.

Paul VI made it impossible for bishops to fight this rejection of Church teaching, since “the Truce of 1968 taught the Catholic bishops of the United States that the Vatican would not support them in maintaining discipline among priests and doctrinal integrity among theologians.”

If this seems a lot to blame on one obscure episode (so obscure that few people remember it, including few Catholics), what else can one say of an act that would “throw a papal encyclical, a solemn act of the Church’s teaching authority, back in the Pope’s face” (even if the Pope collaborated in his own disfacement)? Weigel makes a great deal of modern Church history depend on Paul VI’s refusal to enforce his own document in the District of Columbia:

Advertisement

The Pope, evidently, was willing for a time to tolerate dissent on an issue on which he had made a solemn, authoritative statement, hoping that the day would come when, in a calmer cultural and ecclesiastical atmosphere, the truth of that teaching could be appreciated. The mechanism agreed upon to buy time for that to happen was the “Truce of 1968.”

…What if Cardinal O’Boyle had tried different means to maintain discipline among the priests of the Archdiocese of Washington? What if the press had not decided that the “man bites dog” character of “Catholic dissent” was a wonderful story line? What if a different mechanism for resolving this bitter conflict between a local bishop and his priests had been adopted? Catholics will be debating those questions for decades to come.

No, they won’t.

Weigel argues as if the entire reaction to Humanae Vitae hinged on these nineteen people in Washington. The refusal to accept the document condemning contraception was worldwide and instantaneous. People had not waited to see what would happen to “the Washington nineteen.” Defiance was more ominous among bishops than among seminarians. Many bishops said that Catholics should consider the matter seriously, but follow their own conscience. A Benedictine priest, surveying the impact of this response according to the numbers in the bishops’ dioceses, calculated that only 17 percent of Catholics worldwide were told by their bishops that they must obey the encyclical. Fifty-six percent were told that one could, after conscientious reflection, disagree, and not—as the Scandinavian bishops put it—“be regarded as an inferior Catholic.” Twenty-eight percent were given only equivocal signals from their bishops.2

Weigel never asks in his book why this extraordinary reaction occurred. To him it is just a manifestation of a culture of dissent. A large number of bishops disagreed, in his view, just because they wanted to disagree. Their consciences were somehow pre-deadened. But the real reason for the disagreement is not far to seek. They did not believe what the Pope was saying because it is unbelievable. Remember, the teaching on contraception is not in Scripture or any other form of revelation. The Pope himself says that it is a conclusion from natural law, which can be attained by natural reason, given good will and minimal intelligence. That is, not only all Catholics but all thinking people should recognize this natural truth, just as they do the fact that two and two is four. Papal authority should not be needed. It is not even appropriate. As John Henry Newman said, “The Pope, who comes from Revelation, has no jurisdiction over Nature.”3 He cannot make two and two equal five. And the truth that two and two equal four does not need his proclamation.

When I asked a conservative Catholic academic why the world at large does not recognize the truth of this particular consequence of natural law—the ban on contraception—he said that only the West fails to see it. When I pointed out that the West formulated the concept of natural law, he admitted that, but said that the West was corrupted by the Enlightenment and can no longer recognize natural truths. The deadening of conscience must go further back, then, than the Truce of 1968.

If non-Catholics have trouble seeing this natural truth, Catholics themselves have a special reason for rejecting it. Paul VI set up an excellent laboratory for testing the truth of this natural law precept. Before issuing his encyclical, he expanded a commission of devout and learned Catholics—laymen and laywomen, priests, theologians, bishops—assembled in Rome to study it. Here was the ideal forum to see what people with good intent, with talent and experience, with consciences formed long before there was “a culture of dissent,” would say about the matter in the very bosom of the Church. Some were experts on natural law, and other experts were consulted. Surely if the natural law was as the Pope said, these people of all people would be able to grasp it.

But a majority could not—not even after a last-minute attempt to change the outcome by rushing in more bishops and taking away the votes of the laypersons. Even then, a majority could not recognize the truth the Pope called perspicuous in nature. The commission had good reason to know that the Pope could be wrong on this issue. Even Paul VI tacitly admitted that Pius XI was wrong in his 1930 encyclical when he said that the scriptural account of Onan condemned contraception. All Bible scholars, including all Catholic ones, now deny that the Scripture supports this argument, and Paul did not use it in Humanae Vitae. If the Pope could be wrong about the Bible, which is more within his domain, then he could clearly err on matters of natural reason.

Advertisement

The very existence of this panel was supposed to be a secret, and its report was to be sequestered. The Vatican wanted it to disappear down the memory hole. But the facts about it were leaked to the National Catholic Reporter, and Catholics could see that some of their most intelligent priests and laypersons were considered too dumb to understand natural law. (Many were familiar with those on the commission, and respected their past services to the Church.) But the Pope had succumbed to a “thin end of the wedge” argument—if he allowed dissent here, it would open the way to dissent elsewhere. Actually, the wedge was aimed in the other direction. Insisting on this unbelievable thing made it hard for the Pope to defend “life issues” even where there were somewhat better arguments—on, for instance, euthanasia or abortion. As many Catholics now have abortions as non-Catholics in general, and their rate is 29 percent higher than for Protestants.4

The current pope has dug himself deeper into this disaster. The Vatican, to defend its condemnation of all “artificial contraception,” has issued statements that an HIV-positive man cannot use a condom with his wife; it has also said that condoms cannot be distributed in areas of Africa stricken by plague. I recently heard two priests, Joseph Fessio, S.J., and John McCloskey (spokesperson for Opus Dei), say that if the Church changes the teaching on contraception, it will cease to exist. Just think—all the original and saving truths of the Church (creation, incarnation, resurrection, the sacraments, last judgment, eternal life) are not worth a thing if condoms are allowed. Every other aspect of Catholic life and thought through the ages is held hostage to this one “truth.” This seems a high price to pay just to spare a pope the embarrassment of admitting that he can be wrong on some things. Yet Weigel thinks that the answer to the problem of “fidelity” is simply to keep on insisting to Catholics that everyone must believe everything, even the unbelievable. That is what Weigel calls the courage to be Catholic. This is the “courage” of a man standing in the middle of the road and violently dealing blows to his own head. Luckily, the real Church, the whole people of God, refuses to give up truth to its own conscience in order to save a spurious papal consistency.

Various polls show Catholics rejecting the ban on contraceptives by 70 to 80 percent—but that understates the reality since the polls include Catholics in their forties, fifties, sixties, and seventies. The shape of the future appears more clearly from an extensive poll funded by the Lilly Foundation in 1998. It polled Catholics in their twenties and thirties, and found support for the ban could not even be reported, since preliminary questioning showed that it fell within the margin of error.5

The conservatives, men like Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, who told Paul VI that he was unable to change the Vatican position on contraception, were doing him a great wrong. They were imposing a shallow consistency that made impossible a deep spiritual reassessment. They were depriving him of a necessary tool in any person’s, even a pope’s, personal growth. They were saying it was impossible for him to repent. In Luke’s gospel (22.32), Jesus even bases Peter’s role on his repenting: “You especially, when you repent [epistrepsas], uphold your brothers.” Robert Southwell, the Jesuit poet executed by Elizabeth I’s government, wrote a series of stunning poems that made the penance of Peter the ground of his sanctity.6 An honest error, an oversight, an accidental defect may not call for repenting. But when error is denied or evaded, when a willed blindness shuts out all considerations but a reputation for inerrancy, one is writing in bad faith, unable to repent what one refuses to face.

Humanae Vitae was written this way, as was Paul’s earlier document, Sacerdotalis Caelibatus (1967), which suppressed the Bible text most relevant to priestly celibacy (1 Corinthians 9.5) and repeated over and over the text of Matthew 19.11–12, which has no application to priests (there were no priests at the time).7 As if in punishment for his stubborn refusal to be honest with himself in either document, Paul VI went into a deep funk for the last ten years of his papacy, which Weigel reprimands as a lack of will to enforce what he had enacted. He was not only reluctant to enforce Humanae Vitae, but even to mention it. He did not issue any other encyclical. He said, famously, that “through some crack in the temple of God, the smoke of Satan has entered”; he would have had to suspect that he had something to do with that, that he had taken the advice of men who were less interested in intellectual integrity than in papal unchallengeability.8

Some claim that Catholic critics of the papacy make too much of Humanae Vitae. But we would gladly ignore the letter and move on, as Catholics tried very hard to forget very fast Pius IX’s preposterous encyclical Quanta Cura of 1864, issued with the attached Syllabus of Errors, declaring that liberty of conscience, freedom of the press, and democratic government were anti-religious positions. Pius honestly believed his own nonsense, just as Boniface VIII honestly thought (and said in the bull Unam Sanctam of 1302) that everyone in the world had to be subject to him. Those popes were wrong, but they wrote in good faith. And they were widely ignored very shortly after issuing their claims. But Mr. Weigel and others will not let us ignore Humanae Vitae. They blame modern troubles in the Church on disregard for the encyclical. They say that people are losing their faith because Church leaders can “throw a papal encyclical…back in the Pope’s face.” I have spent some time asking Catholics whether they have lost their faith, or left the Church, because of criticism of Humanae Vitae. I have not found a single person so far. But I know some people directly, and know of many from report, who left because of the encyclical itself. It is the Pope who was discrediting the Pope, not his critics.

2.

Papal Failure

Weigel says that a “silly season” followed the Second Vatican Council, abetted by “uncertain papal leadership during the fifteen-year pontificate of Paul VI (1963–1978).” But now Weigel’s hero, the present pope, has had twenty-four years to make up for those fifteen. Yet there is less conformity to papal teachings than during Paul’s time, fewer priests coming into seminaries, a far greater demand that women be ordained, and more evident scandal. Why? To take just one matter, 96 percent of Catholics told the Zogby national poll that the Pope should punish any bishop who covers up for pedophile priests. Yet not one of them has been punished. (The only bishops removed were themselves guilty of sexual misconduct.)

To give Weigel credit, he too thinks Cardinal Law and others should be removed from office, so he has to labor hard to come up with excuses for Pope John Paul’s not doing just that. In this process, Weigel blames just about everybody in the Church except the Pope. We are told, for instance, that the Pope is “off the information superhighway.” Why? Paul VI is blamed—he turned the Vatican Secretariat of State into a “super-bureaucracy,” from which information can be extracted only by a skilled secretary, and that kind of leadership “is not always characteristic of Vatican secretaries of state.” Well, does the Pope not communicate directly with his bishops? Yes.

But if the bishops are not frank about certain problems—if, for example, a significant number of US bishops did not alert John Paul II to the real possibility that incidence of clerical sexual abuse during the 1970s and 1980s could become a potential nightmare for the Church—the process of collaboration breaks down.

Doesn’t the Pope have his own emissary to America, the papal nuncio, to see if the bishops are telling the truth? Yes, but:

When the nuncio is not deeply familiar with the culture (including the press culture) of his host country, when he limits his information- gathering to ecclesiastical professionals, and when he fails to alert his superiors that a crisis is imminent, the system breaks down and the pope can get blind-sided by events.

If one pope can create a clogged secretariat of state, why cannot another one—especially one as smart and energetic as this pope was in his first two decades—unclog it? If the secretary of state is incompetent, then the man responsible for his appointment is incompetent if he does not remove him. How many bishops had to tell the Pope something for them to become a “sufficient number”? Weigel is on especially weak ground when he blames the bishops. The Pope has been in office so long that all the cardinals and most of the bishops are his own appointees. And we know what his principal test was for their appointment—precisely the fidelity that Weigel thinks has been lacking.

The way not to be promoted under John Paul was to express any doubt on things like contraception or the ordination of women. Cardinal Ratzinger, the Pope’s doctrinal policeman, took pride in saying that John Paul reversed Paul VI in this respect. Paul, he said, appointed too many bishops who were “open to the world.” Under John Paul, “the criterion for selection, therefore, gradually became more realistic.”9 The result is a hierarchy that accepts (at least formally) what most of the laity rejects, with no communication between the two sides, since one thinks talking about it is forbidden and the other thinks it is futile.

The problem of fidelity, then, was not its lack but the reduction of everything to this test. If a man just said that the bans on contraception and women’s ordination could never change, and were therefore not open to discussion, he was moving smartly along the path to a miter. Other considerations—pastoral concern, intellectual integrity, respect for the laity—mattered little in comparison. The bishops kept their bargain. They toed the doctrinal line. That is why they have not been punished. They were doing what they were hired for. The information highway, so clogged when abuse of the laity is at issue, was wide open for communicating disagreement on doctrine. Pedophile priests could hang around forever, but those who publicly challenged the bans on contraception or women priests were disciplined.

And as John Paul chose bishops who would accept what most Catholics do not, he has favored religious groups that believe the unbelievable and attack anyone who doesn’t. Some of these organizations are secretive or coercive—Opus Dei, the Legionaries of Christ, the Neocatechumens, Communione e Liberazione, Focolare—but that did not matter to the Pope so long as they were doctrinally submissive. The Pope’s priorities were made especially clear in the case of the founder of the Legionaries of Christ, Mexican Father Marcial Maciel Degollado. In 1997, nine respected professional men told Rome that Maciel had molested them when they were in his seminary. These men were not seeking money. One of them made his statement on his deathbed, before receiving the sacraments. They proceeded according to Church law, filing a Canonical Request.

The investigation was aborted by Cardinal Ratzinger. The information highway was closed down. Maciel was promoted; he is now a Vatican official, and accompanied the Pope on his recent trip to canonize Juan Diego, a favorite cause of Maciel though most historians doubt that Juan Diego ever existed.10 Why should any bishop think that investigating allegations about sexual misconduct is high among the Vatican’s concerns when it refused to conduct one of Maciel? Statement after statement out of the Vatican and its emissaries has told the bishops not to give in to press hysteria or an intruding state. I listed seven such statements, issued last spring, in an earlier article for this journal.11

To them can now be added the words of a man often mentioned as a possible pope, Cardinal Norberto Rivera Carrera of Mexico, who told an Italian journal after the bishops had met in Dallas and adopted their Charter for the Protection of Children that the “persecution” of Cardinal Law in Boston resembles “what happened in the past century with persecutions in Mexico, in Spain, in Nazi Germany and in communist countries.”12 George Weigel may think the pope should punish Cardinal Law. But those who are even more attuned to Roman values are sure that he will not join such a “persecution.” Cardinal Law, after all, professes a belief that contraception is opposed to natural law. What do raped children mean in comparison with that?

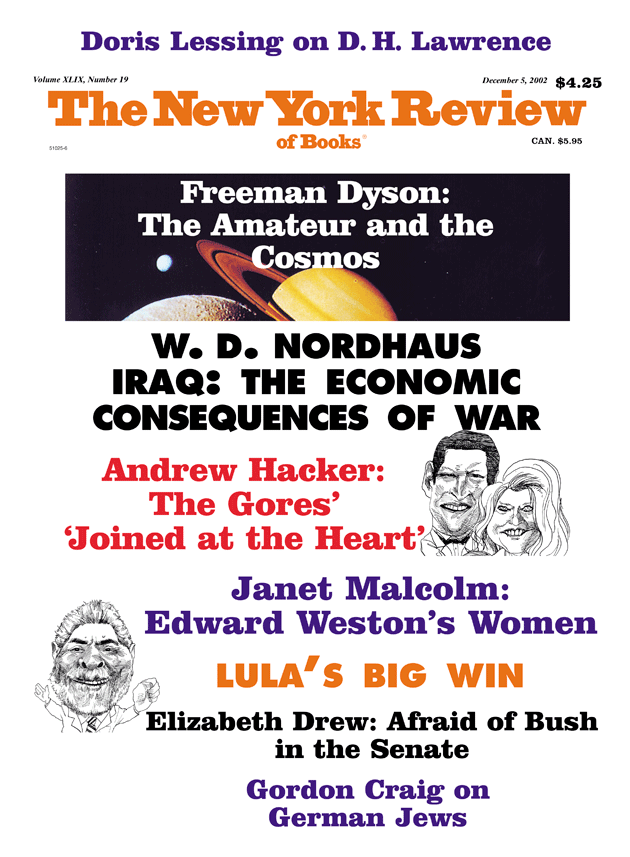

This Issue

December 5, 2002

-

1

See Michael Paulson, “Keating’s Test of Faith,” The Boston Globe, September 29, 2002: “His most frequent references, in conversation, are to the most conservative analyses of the church crisis, including Goodbye, Good Men, a critique of American seminaries… and The Courage to Be Catholic, by papal biographer George Weigel.” ↩

-

2

Philip Kaufman, Why You Can Disagree and Remain a Faithful Catholic (Crossroad, 1991), pp. 72–73. ↩

-

3

John Henry Newman, “Letter to His Grace, the Duke of Norfolk,” Newman and Gladstone: The Vatican Decrees, with an introduction by Alvan S. Ryan (University of Notre Dame Press, 1962), p. 133. ↩

-

4

Stanley K. Henshaw and Katheryn Cost, “Abortion Patients in 1994– 1995: Characteristics and Contraceptive Use,” Allen Guttmacher Institute, Family Planning Perspectives, Vol. 28 (July–August 1996), p. 142. ↩

-

5

Dean R. Hogue, William D. Dinges, Mary Johnson, Juan L. Gonzales Jr., Young Adult Catholics: Religion in the Culture of Choice (University of Notre Dame Press, 2001), p. 200. ↩

-

6

Robert Southwell, “Saint Peter’s Complaynte,” “Saint Peter’s Afflicted Mind,” “Saint Peter’s Remorse,” and “Saint Peter’s Complaint.” On the last poem, which runs to 792 lines, see Mario Praz, “Robert Southwell’s ‘Saint Peter’s Complaint’ and Its Italian Source,” Modern Language Review, July 1924, pp. 273–290. ↩

-

7

To quote from the two texts: ↩

-

8

See Peter Hebblethwaite, Paul VI: The First Modern Pope (Paulist Press, 1993), p. 595. ↩

-

9

Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger with Vittorio Messori, The Ratzinger Report: An Exclusive Interview on the State of the Church (Ignatius Press, 1985), p. 65. ↩

-

10

The important case of Maciel is the subject of a forthcoming book by the two men who broke the story in the Hartford Courant (February 23, 1997) and the National Catholic Reporter (December 7, 2001), Jason Berry and Gerald Renner. Their book, Vows of Silence, will be published by the Free Press, date TK. ↩

-

11

“The Bishops at Bay,” The New York Review, August 15, 2002, pp. 9–10. ↩

-

12

John J. Allen Jr., “Another Cardinal Says Sex Abuse Scandal Results in ‘Media Campaign of Persecution,'” National Catholic Reporter, July 19, 2002. ↩