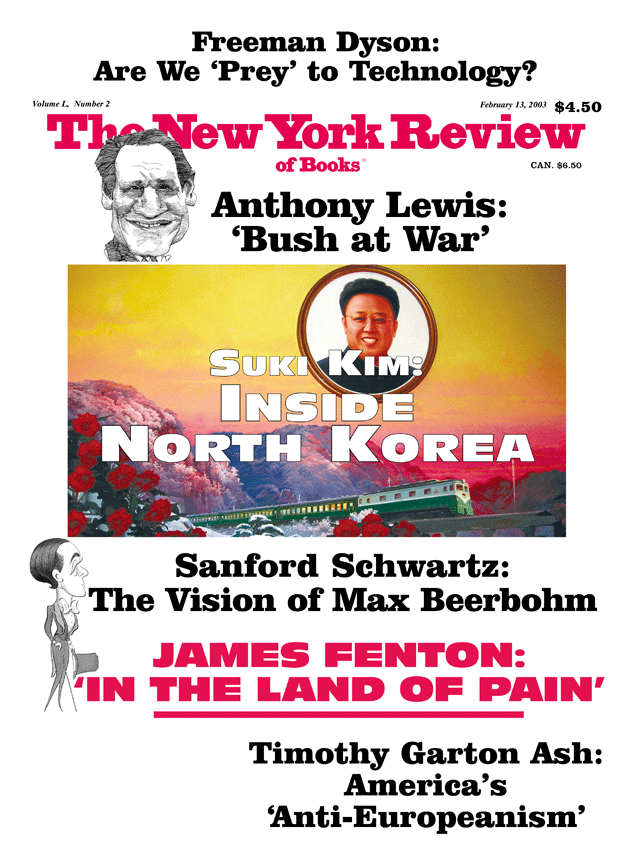

1.

On February 16, 2002, the sixtieth birthday of the Great Leader Kim Jong Il, I was standing in front of a group of Workers’ Party leaders in Pyongyang, singing a South Korean protest song called “Morning Dew.” It was a strange situation for a fiction writer from New York’s East Village who is neither a political activist nor an entertainer. I am South Korean by birth and an American, having immigrated at thirteen. The American in me dismisses North Korea as off-limits, the bastard child of the cold war. But I am often haunted by the photographs of famine there that I see on the evening news. When friends ask me whether I think the two Koreas will ever be reunified, I never know what to say. I know as much as they do, or as little. The one thing that sets me apart is that I am certain, no matter how evil North Korea is supposed to be, that I could never hate its people.

The story of my journey began in the fall of 2001 when I wrote a letter to Yoo Tai Young, the head of the Korean American National Coordinating Council (KANCC), asking how I might obtain a visa to go to North Korea. A retired minister of the Bedford Park Presbyterian Church in the Bronx, he is well known among New York’s Korean-American community for his activities on behalf of North Korea. If you want to find a way to Pyongyang, several people had advised me, you should get in touch with Mr. Yoo. Very few Americans have been issued visas in recent years, and I doubted that he could arrange one for me. But after an interview with the KANCC’s representative, I received, in an envelope bearing the return address of Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, a simple form entitled “Homecoming Application.” The key question on it was whether I could supply the name of a family member in the North. I filled in the blank, writing the name Yoon Nam Jung. Age 68. Relation, maternal uncle. Address not known.

On June 25, 1950, when North Korean bombs began dropping on South Korea, my grandmother fled her home in Seoul with her five children, including my then-four-year-old mother. Cars were rare, and the only means of escape was on foot or by train. Seoul Station was packed with panicked citizens fighting to get on the southbound trains. The family had finally secured seats for themselves when someone screamed that young men should make room for women and children. The last thing my grandmother recalled was that her eldest child, then seventeen years old, rose from his seat. “Don’t worry, Mother,” he told her. “I’ll be on the next train.” Except that hers was the last train out of Seoul. Later, neighbors reported seeing him, with his hands tied, being dragged away by North Korean soldiers.

My grandmother spent her remaining years in search of her lost son. She would often wander around the city muttering his name. Her only solace was the prayer rituals during which the local shamans reassured her that he was alive somewhere near Pyongyang. Korean Confucian ethics hold that there is no bigger sin than abandoning one’s family. Despite the stroke that debilitated her later in life, she kept herself going, waiting for the 38th Parallel to break open.

On February 9 last year, amid the ebullient homebound crowd at the Korean Airlines lounge in Kennedy Airport, I met Mr. Yoo, who turned out to be a silver-haired man in a Lenin beret and a musty green trench coat. Something about him seemed stuck in another era: the way he insisted on referring to me as Miss Kim, or the way he always spoke for me to the Workers’ Party leaders we encountered later that week. During the nearly twenty-hour flight to Beijing, which included stopovers in Anchorage and the South Korean airport at Incheon, I learned that there would be twelve members in our party, the rest of whom we would meet in Beijing. There we would stay overnight before flying to Pyongyang.

Air Koryo—North Korea’s only airline—has flights between Beijing and Pyongyang only two days per week. Since Pyongyang is less than a four-hour drive from Seoul, the detour through China was yet another reminder of the division of the countries. Relations between North and South improved under South Korean President Kim Dae Jung’s “sunshine” policy of reconciliation, which was supported by Clinton. But the Bush administration’s hard-line position has reversed the agreements made at the Korea summit meeting in 2000. Nor did the “Axis of Evil” speech by President Bush help to ease the tension. So I was surprised to have been admitted to the country. I still did not know if an invitation to the celebration meant that they had found my uncle.

Advertisement

Yoo spoke to me on the trip only once. As we were nearing Incheon Airport, he suddenly turned to me and the pair of stewardesses perched near us and asked, “Do you know where we’re headed?” When they shook their heads with intrigued expressions, he blurted out with a boastful grin, “I’m going home. No, not Seoul, that’s not my home.” He was, he told us, born in Hwanghae Province, south of Pyongyang, and had fled from home in 1950 when he was nineteen. After fourteen years in South Korea, he spent thirty-six years in America. “Home is back North,” he said. “I’m sixty-nine years old, but the only home I’ve ever had belongs to those first nineteen years. When you get to my age, you know there’s only one home.”

Beijing, on February 11, was ablaze with the lunar New Year’s Eve festivities as we arrived. The other members of our party were already there, divided into three groups. First, there was the “artistic team,” consisting of a conductor, a violinist from the Boston Symphony Orchestra, a soprano from Los Angeles, and a baritone from New York. They had been hired to perform at Kim Jong Il’s sixtieth-birthday celebration. Then there were three “supporters”: an elderly man from Los Angeles on his way to be reunited with his seventy-one-year-old sister, an installation artist wearing a beret and sideburns who claimed to be bringing an artwork for the Great Leader, and an evangelist from a gospel church on a humanitarian mission. Lastly, there were the “delegates,” core members of KANCC, the US-based organization of pro–North Korea activists. Mr. Yoo and a second member named Kim Bong Ho were permanently forbidden entry into South Korea because of their anti-government activities. Two others, Oh Bo Yong and Yi Chang Il, were die-hard loyalists of the North Korean regime. Why I was billed as the fifth delegate was not made clear to me until days later.

Our Air Koryo flight the next day was full. Most of the passengers, dressed in suits and furs, appeared to be diplomats from the former Eastern bloc and Southeast Asian countries. Many wore tiny red badges showing a picture of either Kim Il Sung, the “Eternal Great Leader” or “Eternal President,” who died in 1994, or his heir, Kim Jong Il, the “Great Leader,” also known as “Great General” or “Respected General.” The delegates were speaking with distinct North Korean accents now, addressing one another as “comrade.” Suddenly liberated, even buoyant, these men in their sixties and seventies were bursting with childlike excitement.

Upon boarding the aircraft, I was immediately struck by the martial music, the sort that would be played at a military procession. It soon drifted into a melodic song about the Great Leader, Kim Jong Il. The stewardesses in navy-blue suits and white blouses and gloves were in their early twenties and uniformly pleasant-looking. What struck me about them, other than the Kim Il Sung badges across their chests, was that they did not smile.

The interior of the plane was light green. From its wall panels and its command knobs to its overhead luggage compartments, everything was made of either linoleum or plastic. The fluorescent light cast a somber shadow. The seatbelt signs never flashed on. The in-flight magazine had on its glossy cover a picture of Kim Jong Il with his right arm stretched out, pointing at a red banner with the words “Chosun” (North Korea’s name for itself) and “Juche 91.” Juche, meaning self-reliance, is the central concept promoted by the regime, and it is often attached to significant words or events, in this case to the ninety-first year since Kim Il Sung’s birth.

In just ninety minutes, the plane arrived at the North Korean capital, which had been a source of heartbreak for generations. My grandmother until the day she died could never grasp why she was not allowed to cross the 38th Parallel. Now, fifty-two years since the war, twenty-seven years since she died, two weeks after Bush had called it part of the Axis of Evil, I was flying into the taboo land, holding on to my American passport as though it were a shield.

My first glimpse of the country was of serene, empty patches of farmland below. Only four other planes were parked on the runway as we landed, three Air Koryo aircraft and one bearing a “Vladivostok” sign in red. Stepping onto the tarmac, I was struck by the huge portrait of Kim Il Sung on top of a lone concrete building from which a crowd of dark-suited men were walking toward us. I heard my name called from several directions. Suddenly I was being pulled to one side, to pose with the other delegates before flashing TV cameras. A mob of reporters surrounded us. One of them was holding up a sign that read, “Delegates to the Gathering to Meet the Sun of the Twenty-first Century.”

Advertisement

The customs officials confiscated my cellular phone and my passport—both, they reassured me, to be returned when I left. The narrow baggage-claim area was chaotic. Suitcases were thrown about everywhere, and people were frantically searching for them in the dark. Soon I was being led away by a grinning man in his late forties, who effusively said that he had been looking forward to meeting me and offered his coat when he saw me shivering in the cold. Someone introduced him to me as an ambassador, the head of the North Korean Permanent Mission to the UN.

The delegates were ushered into two cars: Yoo into a blue Mercedes-Benz 200 and the rest of us into a van. We drove past frozen fields sparsely dotted with huge cement blocks that appeared to be housing projects. We saw hardly any cars. A few people were walking on the side of the road, some in khaki military uniforms, others bundled up in dark coats. Soon more dilapidated concrete buildings came into view, most of them less than ten stories high, and many without windows. Shops were few and plainly marked as “Fish Shop” or “Fruit Shop.” The signs were in old Korean words no longer used in South Korea. The display windows were each covered by a cloth. At bus stops, long lines of people were waiting with no bus in sight. A tram went by, followed by a few people on bicycles.

The smog cast a strange halo over the gray city. The only visible color was the red on posters marked “2.16,” the date of Kim Jong Il’s sixtieth birthday, hanging on every pole. Slogans on billboards filled the empty skyline. One read, “Our Great Leader Is Always with Us.” Another said, “We Are Happy.” The van finally pulled up at the foot of a paved hill called Man-Su-Dae, on top of which stood the sixty-five-foot-high bronze statue of Kim Il Sung. Everyone is supposed to pay his or her respects to the Eternal Great Leader upon arrival in Pyongyang, and we were told to bow while Yoo placed a bouquet on the ground below.

The special quarters for delegates are perched on a hillside about a ten-minute drive from Man-Su-Dae. Built around what appeared to be the remnant of an orchard, the two-story cement building had so little distinction that if I were to go back, I doubt I could recognize it. As with a conference center or a dormitory, the rooms were identical. The first things I noticed in mine were the large portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. The bookcase was filled with volumes about and by the Eternal Great Leader and the Great Leader. A calendar displayed a snow-covered nativity scene on top of Mount Baek-Du, where Kim Jong Il is said to have been born under double rainbows and a bright star. In the corner of the mahogany-paneled bathroom stood a Japanese-made sauna, although I never managed to make it work. There was no hot water and the electricity was erratic. Some nights I forced myself to go to sleep early because the light in my room would not turn on, no matter how often I flicked the switch. The heat was also slow in coming, so that I kept my coat on almost the whole time I was there.

At dinner on the first night, I found myself sitting next to an elderly man with a lean face and gold-framed eyeglasses. In his navy-blue jacket, he seemed the picture of a revolutionary. Without a doubt one of the handsomest men I had ever seen, Shin Byung Chul was director of the Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries. He turned to me and said that he envied writers. Even the Great Leader, he said, had once reflected that had he not been a leader, he would have been a writer. My first visit, he hoped, was only an introduction to later ones. I would soon be able to free myself from the lies that the US and South Korean governments have fed me and see the truth about North Korea—and perhaps, he said, I might even be moved to write about it.

It dawned on me then why I had been chosen to be a delegate. It had nothing to do with a reunion with my uncle. They needed a Korean-American writer who understood the Korean language and culture and had a family connection with the North. For the most isolated country in the world, it was a bold move to take a chance on me. “But until you get to know us,” Shin said tersely, “it would be foolish to write anything.” I took his words as a warning. As he filled my glass with rice vodka, I felt a chill running down my back. Across the room, the television set, which was turned on at every mealtime, showing news exclusively about Kim Jong Il, kept flashing images, among which I saw myself. We were the latest news, I realized. Everyone on our plane had specifically been chosen to hail the “Sun of the Twenty-first Century.”

2.

The weeklong celebration began with the ceremony at the Kimjongilia Exhibition in the Grand Peoples’ Study House, presented by the Korean Kimjongilia Federation. The young guide, shivering in her flimsy lilac hanbok (Korean traditional dress), explained that the Kimjongilia, an oversized red flower that resembles a poinsettia, was the creation of a Japanese horticulturist named Kamo Mododeru. The red petals, she told us, symbolize the Great Leader’s passionate nature; the stem can grow to one meter, straight and fearless like the Great Leader; the heart-shaped leaves celebrate the generous heart of the Great Leader; the slight downward angle of the petals evokes the way the Great Leader always watches over his people.

Over 14,300 Kimjongilias were lined up against the walls of the four floors of the exhibition hall, where organizations ranging from the Supreme People’s Assembly and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the Ministry of the People’s Armed Forces occupied booths. Our guide led us from a display of the Agricultural Committee’s hand-picked 216 red-colored kernels of grain to the Ministry of Railways’ illustration of a train in which the Great Leader once rode. The Computer Center presented the portrait of Kim Jong Il on a flat panel screen, with Kimjongilias arranged as a keyboard. Weary from seeing the same name everywhere, I stared at the ceiling only to find it plastered with slogans. A quote by Kim Jong Il read, “The one believing in the people will be given healthy medicine but the one betraying the people will be given poison.”

The Great Leader himself was nowhere to be seen. He never attended the February 16th anniversary celebrations, I was told by Consul Bae, an official from the Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries who became my constant escort and even slept in the room next to mine. To save time, he told me, the Great Leader took catnaps in cars and ate rice balls. He wore a tattered jump suit year after year. He traveled tirelessly, supervising workers wherever they were. Thus the song, “Dear Beloved General, Where Are You?” This year, he even tried to dissuade the people from holding celebrations. “But what son would ignore his own father’s sixtieth birthday!” Bae said, gazing lovingly at the portrait of Kim Jong Il. Whether in the figure skating, water ballet, or musical programs, a single theme was omnipresent. The skaters glided to “General Kim Jong Il’s Song.” The ballerinas dived underwater to resurface as the petals of Kimjongilias. The singers bellowed out songs with titles such as “Dear General Galloping on a White Horse.”

One song called “February Is Spring” puzzled me until Bae explained that February, officially a winter month, was really spring because it marked the Great Leader’s birth. The gymnastic show entitled “Under the Banner of Army-Based Policy” featured ten thousand boys and girls between the ages of eight and fifteen in a grand jigsaw puzzle that formed the Party emblem of a hammer, a sickle, and a brush. “You’ve never seen anything like this, have you?” Bae said, studying my face for approval. “For the Arirang Festival of April 15—the birthday of Kim Il Sung—we have a hundred thousand kids practicing!”

For me, each event was followed by “get-to-know North Korea” sessions, which included a private meeting with the publisher of a journal called Unification Literature and a visit to Kim Il Sung University, where I was greeted by two women professors and a third-year student of poetry named Kim Ok Kyung. Although I met with them separately, they all answered my questions identically. Upon being asked to recommend readings, they all suggested Kim Chul, whose poem “Mother” had been praised by the Eternal Great Leader. Their favorite foreign book was, oddly, Gone with the Wind. Scarlett, the publisher said, was the new bourgeois heroine. It occurred to me that it is not only a story about a civil war between North and South, but also about Scarlett, who chooses her homeland over everything. And, of course, the North wins.

Still, it was refreshing to see a college campus. Except for the bronze statue of Kim Il Sung towering near the entrance, it seemed not so different from most American schools. There was the familiar sight of students rushing about everywhere; girls in groups of three or four, laughing and chatting; boys trailing behind with bundles of books under their arms. Encouraged by the cheerful scene, I turned to Kim and asked what she wanted to do after graduation. With heartbreaking sincerity, she answered, “I want to write poems worthy of our Great Leader.”

Another “must see” was Juche Tower, designed by Kim Jong Il, who had also written six operas in two years. Although the 558-foot-high marble structure commemorated the founding of North Korea, I was more interested in the guide who stood trembling against the biting wind. Like most guides I met, she was young and pretty. She kept peering at me in ways that made me wonder if she might be as curious about me as I was about her. Quickly glancing at the direction of Consul Bae, she remarked, “I am sorry to hear about the disaster in your city.” She was referring to September 11. “Were there any Koreans in those buildings?” I was about to answer when I caught Bae glaring at me; there were to be no conversations, except about the Juche Tower. He ushered me away to the National Museum of Fine Art, where I was met by another guide who led me past the paintings, most of which portrayed Kim Jong Il in various poses as a heroic leader.

On my second day, Chang Kyung Ryul, the head of the Research Center for Socialist Philosophy, came to see me and some of the other delegates for a “free discussion on Juche.” According to Chang, the Juche concept of self-reliance means that man is in charge of his destiny and must devote his actions to the good of his people. He asked, “In America, does man own his own destiny?” Yoo volunteered, “In the US, man is owned by materials. There’s no love for humanity, only for materials.” Chang clicked his tongue and said, “How ironic then that they should call us evil?” Yoo said bitterly, “America’s way of loving its people is to destroy other nations. Look what they’re doing in Afghanistan. Look how Bush blabbers that evil rubbish, all just to sell off the outdated F-15 to South Korea. They don’t care what they do to the rest of the world as long as they fatten themselves up.”

The delegates were firm in the belief that the Korean War had never been a war among Koreans, but an instrument of the cold war. Along with the former Soviet Union, they claim, the US had been responsible for dividing Korea in two. This belief is the basis for anti-American sentiments on both sides of the 38th Parallel. North Koreans and many South Korean liberals have long dismissed the South Korean regime as being the puppet of the US and blamed the US for standing in the way of reunification. What I did not suspect was that North Korea’s entire political system seemed to be driven by hatred of the US. Juche, from what I gathered, had as much to do with America as it did with both Koreas.

Among the delegates, Yi Chang Il sounded the most zealous. At seventy-two, he was in charge of documenting the KANCC mission. He kept prodding me to write on behalf of the reunification effort; of course, he added, the Party would have to approve the final draft. Like Yoo, Yi had been born in Hwanghae Province in the North. He was a high school biology teacher and had made his way to the South. “I fled alone, leaving my family behind,” he sighed. “We were terrified that America was going to bomb us, the way they did Hiroshima. Back then, we never imagined that the 38th Parallel would outlive us.” He insisted that the real Korea was the North. “Everything’s Korean here,” he said. “No English billboards, no Western values popular among those young South Koreans.” It could be a dream come true, I realized, to arrive at the long-lost homeland to find its landscape much the same as it was over fifty years ago. What I found to be derelict, he welcomed as home.

Kim Bong Ho considered himself a revolutionary stationed in the US. Originally from South Korea, he was, at forty-five, the only one of the group born after the war. Although his manner was as meek as a Korean farmer’s and his puffy eyes often crinkled with laughter, he was elusive about his past, and at times looked sad. Kim had majored in French literature at Seoul’s Koryo University (one of the most prestigious colleges in South Korea), but he had never graduated and emigrated to the US in the Eighties. His return to South Korea was officially blocked; but he said, “It means nothing to me. I don’t have any reason or wish to visit that country.” Whatever had driven him out of South Korea seemed final. I then recalled that throughout the 1970s and 1980s, when he lived there, student demonstrations against the dictatorship broke out in many cities. As with the Tiananmen Square students, those in South Korea were systematically imprisoned and murdered. One of the bloodiest uprisings, the Kwangju Massacre of May 1980, left 191 dead, according to the government, although Kwangju citizens claim that the figure is closer to two thousand. A few students ended up escaping the country and never looked back. I suspect Kim was one of them.

On February 15, I was invited to attend a televised “Central Report Meeting” at the “4.15 Hall of Culture.” Over six thousand Party members, members of the armed forces, and foreign dignitaries were gathered in an unheated auditorium. As the band played “General Kim Jong Il’s Song,” the senior Party and state officers emerged from behind the curtain and took their seats on stage. For a second, it was not clear who was watching whom. Were we the audience, or were the men in their uniforms glaring down from the elevated podium expecting something from us? The stillness was broken only by clicking cameras. Consul Bae told me to look straight at them.

Jo Myong Rok, the first vice-chairman of the National Defense Commission and the political director of the Korean People’s Army, read a message to the Supreme Commander Kim Jong Il, in which he praised the people’s devotion and loyalty to their leader. Next came Kim Yong Nam, a politburo member of the Central Com- mittee of the Workers’ Party of Korea and the president of the Presidium of the Supreme People’s Assembly, who praised Kim Jong Il for possessing a “profound idea and theory, unique political mode and outstanding leadership ability.” In conclusion, he read, “if the US imperialists and their followers dare provoke a war in this land, it will lead to their final destruction.”

For nearly two hours, a stream of Party leaders read congratulatory messages to the absent Great Leader while everyone applauded, shouting “Hail Kim Jong Il!” On the drive back to the delegates’ quarters, I saw thousands of people on Kim Il Sung Square practicing dance steps for the celebration. Some were waving the Party flag. Some were holding hands, circling to the music. The temperature was below zero and they had, I was told, been there for days.

I became more and more depressed. When I was brought to view the Eternal Great Leader, whose body lay embalmed under glass in a marble mausoleum, I bowed from each side of the bier with only a quick glance at his all-too-familiar face. It looked eerily alive. I was then invited to witness the family reunions held in the Koryo Hotel, where groups of old people waited nervously in the lobby to see their relatives, but I could hardly bear watching them. Although Yoo had met with his family before, his steely face broke at the sight of his eighty-two-year-old sister who, white-haired and stooped, walked with difficulty even with a cane. She had brought him homemade bean cakes. They talked for approximately two hours.

While they sat huddled over a lunch of cold buckwheat noodles, a group of Party officers watched them from the next booth. Apparently reunions were allowed only within the hotel. Yi Chang Il, who was granted a visit of a few hours to his sick sister in Hwanghae Province a couple of hours away, was the exception because he had proven himself loyal to the Party. But he was still prohibited from stopping at his parents’ graves, less than a mile from his sister’s house.

After Yoo had been reunited with his sister, Consul Bae said, probably trying to raise my spirits, “We will locate your uncle. I give you my word. Give us a month, and we will find him.” I did not tell him that I no longer believed my uncle was alive. And even if he had managed to survive, I was no longer sure that I wanted to meet him. My grandmother was long gone. So was her lifetime of sadness and anger after her firstborn was taken away. Now here I stood in her place, a granddaughter, a niece, a writer of fiction, a New Yorker with capitalist habits. How could I tell my sixty-eight-year-old uncle, if he was alive, that I saw no relief for his kind of loss—a mother, a homeland, a life that should have been but never was? I began to regret having come to North Korea at all.

3.

When February 16 finally arrived, I was seated next to Pak Kyung Nam, vice-chairman of the Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, at a celebratory dinner, which included delegates from Australia and Germany, and a few selected Party officers. It was clear that Pak, a portly and rumpled man in his sixties, was the highest-ranking official there. Someone whispered that he worked directly under the Great Leader. I was told to fill his glass with Johnnie Walker. Although his face was stern and menacing, he seemed to be imploring when he said it was up to people like me, second-generation Korean-Americans, to tell the world the truth about North Korea. He then urged me to try the pheasant ball soup and roe deer meat, which had been personally sent by the Great Leader.

As the evening went on, the delegates grabbed the microphone and began singing pre-war North Korean tunes. A boyish man in his mid-forties, the Korean delegate from Germany, belted out a Sixties South Korean pop song called “Daejun Blues,” replacing “Daejun” with “Kwangju,” the South Korean city of the bloody riots. As he sang, his eyes were closed, as though he were recalling a memory. After the final note, he cried out, “My home is eternally Kwangju. Dear comrades, don’t ever forget my Kwangju!”

I knew that it would soon be my turn. Choosing the right song seemed impossible until someone whispered “Morning Dew.” Of course, it made perfect sense. “Morning Dew” by the South Korean folk singer Kim Min Gi has been the song of protest demonstrations in the South for decades:

When sorrow collects in my heart

bead by bead like morning dew

finer than pearl between each leaf

after a long, wakeful night,

I climb the morning hill

and attempt a small smile.

The sun rises red over the graves.

The midday heat must be my trial.

Here I come, to that wild field.

Here I come, leaving behind every sorrow.

It had been years since I’d thought of that song. Certainly I’d never imagined that in Pyongyang in 2002, surrounded by Workers’ Party leaders, I would recall the South Korean students who had perished in the name of democracy and reunification. The room was still as I sweated through “Morning Dew.” Afterward, Vice Chairman Pak patted me on the shoulder and offered me a shot of vodka. I looked at him, feeling sadder than I had felt the entire week. He—like me, my lost uncle, Yoo Tai Young, Kim Bong Ho, Yi Chang Il, Director Shin, Consul Bae—was part of what had once been a five-thousand-year-old Confucian country called Korea. We all shared one thing. We deplored the existence of the 38th Parallel.

The evening ended with the Party leaders all rising. Arm in arm, they sang the “Comrade’s Song.” They were men driven by purpose. They believed that they were patriots. They lived for Kim Jong Il, who, they were certain, would reunite us. At that moment, I thought they looked happy.

Yet I could not stop crying. As the days passed, the city became more distant. It seemed that I was always inside a car looking through the glass. There was hardly any traffic. The people I saw on the wintry streets never returned my gaze. Even if I shouted to them, they would not have heard me. What separated us was thicker than the car window. There have been at least 150,000 political prisoners in North Korea, and 400,000 of its people have perished as a result of persecution. Today 60 percent of all children under five are malnourished. Over two million people have died from famine. The regime, according to its own recent revelations, has been devoting huge resources to developing atomic weapons while denying it was doing so. But I was never allowed to see any of these realities.

On February 19, landing in Seoul’s new Incheon Airport, built to become the world’s largest in preparation for the approaching World Cup, I returned to the twenty-first century. President Bush was due to arrive later that day. Thirty-two South Korean students had just been arrested for invading the US Chamber of Commerce. Seoul’s streets were covered with banners saying “US Must Stop Waging Wars in Korean Peninsula,” “US Must Apologize to North Korea,” and “Go Home.” Somewhere, in some corner of Seoul, I knew there were students chanting “Morning Dew.”

This Issue

February 13, 2003