1.

In his earliest childhood recollection, young Bruno Schulz sits on the floor ringed by an admiring household while he scrawls one “drawing” after another over the pages of old newspapers. In his creative transports, the child still inhabits “the age of genius,” still has unselfconscious access to the realm of myth. Or so it seemed to the man whom the child became; all of that man’s strivings would be to reacquire his early powers, to “mature into childhood.”

Schulz’s strivings would issue in two bodies of work: etchings and drawings which would be of no great interest today had Schulz not become famous by other means; and two short books, collections of stories and sketches about the inner life of a boy in provincial Galicia, that propelled him to the forefront of Polish letters in the interwar years. Rich in fantasy, sensuous in their apprehension of the living world, elegant in style, witty, underpinned by a mystical but coherent idealistic aesthetic, Cinnamon Shops and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass were unique and startling productions, seeming to come out of nowhere.

Schulz had been born in 1892, the third child of Jewish parents from the merchant class, and named for the Christian saint Bruno on whose name-day his birthday fell. The province of his birth was at the time a crownland of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His home town, Drohobycz, was something of an industrial center with oil wells nearby. After World War I Drohobycz again became part of a resurrected Poland.

There was a Jewish school in Drohobycz, but Schulz was sent to the Polish gymnasium, where he excelled in art. His languages were Polish and German; he did not speak the Yiddish of the streets. Dissuaded by his family from becoming an artist, he registered to study architecture at the polytechnic in Lwów, but had to break off his studies when war was declared in 1914. Because of a heart defect he was not called up. Returning to Drohobycz, he set about a program of intensive self-education, reading and practicing his draftsmanship. He put together a portfolio of graphics on erotic themes entitled The Book of I dolatry and tried to sell copies, with some diffidence and not much success.

Unable to make a living as an artist, saddled, after his father’s death, with a houseful of ailing relatives to support, he took a job as an art teacher at a local school, a position he held until 1941. Though respected by his students, he found school life stultifying and wrote letter after letter imploring the authorities for time off to pursue his creative work, letters to which, to their credit, they did not always turn a deaf ear.

Despite his isolation in the provinces, Schulz was able to exhibit his artworks in various cities in Poland and to enter into correspondence with kindred spirits. Into his letters—of which only a small proportion have survived—he poured much of his creative energy. Jerzy Ficowski, Schulz’s biographer, calls him the last great exponent of epistolary art in Poland. All evidence indicates that the pieces that make up his first book, Cinnamon Shops (1934), began their life in letters to the poet Debora Vogel.

Cinnamon Shops was received with enthusiasm by the Polish intelligentsia. On visits to Warsaw Schulz was welcomed into artistic salons and invited to write for literary reviews; at his school he was awarded the title “Professor.” He became engaged to Józefina Szelinå«ska, a Jewish convert to Catholicism, and, though not himself converting, withdrew formally from the Drohobycz Jewish Religious Community. Of his fiancée he wrote: “[She] constitutes my participation in life; through her I am a person, and not just a lemur and kobold…. She is the closest person to me on earth.” Nevertheless, after two years the engagement fell through.

The first translation into Polish of Franz Kafka’s The Trial appeared in 1936 under Schulz’s name, but the actual work of translation had been done by Szelinå«ska.

In 1937 Schulz published a second book, Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass. The book was put together from early pieces, some of them still tentative and amateurish. Schulz tended to deprecate it, though in fact a number of the stories are quite up to the standard of Cinnamon Shops.

Burdened by teaching and by familial responsibilities, anxious about political developments in Europe, Schulz was by this time descending into a depression in which he found it impossible to write. Receipt of the Golden Laurel of the Polish Academy of Literature did not raise his spirits; nor did a three-week visit to Paris, his only substantial venture outside his native land. He set off for what he would in retrospect call “the most exclusive, self-sufficient, standoffish city in the world” in the dubious hope of arranging an exhibition of his artworks, but made few contacts and came away empty-handed.

Advertisement

In 1939, as a consequence of the Nazi–Soviet partition of Poland, Drohobycz was absorbed into Soviet Ukraine. Under the Soviets there were no opportunities for Schulz as a writer (“We don’t need Prousts,” he was told). He was, however, commissioned to do propaganda paintings. He continued to teach until, in 1941, the Ukraine was invaded by the Germans and all schools were closed. Executions of Jews began at once, and in 1942 mass deportations.

For a while Schulz managed to escape the worst. He had the luck to be adopted by a Gestapo officer with pretensions to art, thereby acquiring the status of “necessary Jew” and the precious armband that protected him during roundups. For decorating the walls of his patron’s residence and the officers’ casino he was paid with food rations. Meanwhile he bundled his artworks and manuscripts in packages and deposited them among non-Jewish friends. Well-wishers in Warsaw smuggled money and false papers to him, but before he could summon up the resolve to flee Drohobycz he was dead, singled out and shot in the street during a day of anarchy launched by the Gestapo.

By 1943 there were no Jews left in Drohobycz.

In the late 1980s, as the Soviet Union was breaking up, news reached the Polish scholar Jerzy Ficowski that an unnamed person with access to KGB archives had come into the possession of one of Schulz’s packages, and was prepared to dispose of it for a price. Though the lead ran dry, it provided the basis for Ficowski’s enduring hope that Schulz’s lost writings may yet be recovered. These writings include an unfinished novel, Messiah, as well as notes that Schulz was taking at the time of his death, records of conversations with Jews who had seen the working of the execution squads and transports at first hand, intended to form the basis of a book about the persecutions.*

In Poland Jerzy Ficowski, born in 1924, is known as a poet and scholar of Gypsy life. His main reputation rests, however, on his work on Bruno Schulz. Since the 1940s Ficowski has indefatigably, against all obstacles, bureaucratic and material, scoured Poland, the Ukraine, and the wider world for what is left of Schulz. His translator, Theodosia Robertson, calls him an archaeologist, the leading archaeologist of Schulz’s artistic remains. Regions of the Great Heresy is Robertson’s translation of the third, revised edition (1992) of Ficowski’s biography, to which he has added two chapters—one on the lost novel Messiah, one on the fate of the murals that Schulz painted in Drohobycz in his last year—as well as a detailed chronology and a selection of Schulz’s surviving letters.

Within her translation of Regions of the Great Heresy, Theodosia Robertson has elected to retranslate all passages quoted from Schulz. She does so because, along with other scholars of Polish literature in the United States, she has reservations about the existing English translations. These appeared from the hand of Celina Wieniewska in 1963: it is through them, under the collective title The Street of Crocodiles, that Schulz is known in the English-speaking world. Wieniewska’s translations are open to criticism on a number of grounds. First, they are based on faulty texts: a dependable, scholarly edition of Schulz’s writings appeared in Poland only in 1989. Second, there are occasions when Wieniewska silently emends Schulz. In the sketch “A Second Autumn,” for example, Schulz fancifully names Bolechow as the home of Robinson Crusoe. Bolechow is a town near Drohobycz; whatever Schulz’s reasons for not pointing to his own town, it behooves his translator to respect them. Wieniewska changes “Bolechow” to “Drohobycz.” Third and most seriously, there are numerous instances where Wieniewska cuts Schulz’s prose to make it less florid, or universalizes specifically Jewish allusions.

In Wieniewska’s favor it must be said that her translations read very well. Her prose has a rare richness, grace, and unity of style. Whoever takes on the task of retranslating Schulz will find it hard to escape from under her shadow.

As a guide to Cinnamon Shops, we can do no better than go to the synopsis that Schulz himself wrote when he was trying to interest an Italian publisher in the book. (His plans came to nothing, as did plans for French and German translations.) Cinnamon Shops, he says, is the story of a family told in the mode not of biography or psychology but of myth. The book can thus be called pagan in conception: as with the ancients, the historical time of the clan merges back into the mythological time of the forebears. But in his case the myths are not communal in nature. They emerge from the mists of early childhood, from the hopes and fears, fantasies and forebodings—what he elsewhere calls “mutterings of mythological delirium”—that form the seedbed of mythic thinking.

Advertisement

At the center of the family in question is Jacob, by trade a merchant, but preoccupied with the redemption of the world, a mission he pursues through the means of experiments in mesmerism, galvanism, psychoanalysis, and other more occult arts from what he calls the Regions of the Great Heresy. Jacob is surrounded by lumpish folk, led by his archenemy, the housemaid Adela, who have no grasp of his metaphysical strivings.

In his attic Jacob rears, from eggs he imports from different parts of the world, squadrons of messenger birds—condors, eagles, peacocks, pheasants, pelicans—whose physical being he sometimes seems on the brink of sharing. But Adela, with her broom, scatters his birds to the four winds. Defeated, embittered, Jacob begins to shrink and dry up, metamorphosing at last into a cockroach. Now and again he resumes his original form to give his son lectures on such subjects as puppets, tailors’ dummies, and the power of the heresiarch to bring trash to life.

This summary was not the end of Schulz’s efforts to outline what he was up to in Cinnamon Shops. For the eyes of a friend, the writer and painter Stanisl/aw Witkiewicz, Schulz extended his account, producing a piece of introspective analysis of remarkable power and acuity amounting to a poetic credo.

He begins by recalling two images that go back to his “age of genius” and still dominate his imagination: a horse-drawn cab with lanterns blazing, emerging from a forest; and a father striding through the darkness, speaking soothing words to the child folded in his arms, while all the child hears is the sinister call of the night. The origin of the first image is obscure to him, he says; the second comes from Goethe’s ballad “Der Erlkönig,” which shook him to the bottom of his soul when his mother read it to him at age eight.

Images like these, he proceeds, are laid down for us at the threshold of life; they constitute “an iron capital of the soul”; all of the rest of an artist’s life consists in exploring and interpreting and trying to master them. After childhood we discover nothing new, only go back over and over the same ground in a struggle without resolution. “The knot the soul got itself tied up in is not a false one that comes undone when you pull the ends. On the contrary, it draws tighter.” Out of the tussle with the knot emerges art.

As for the deeper meaning of Cinnamon Shops, says Schulz, it is not a good idea for a writer to subject his work to too much rational analysis. It is like demanding of actors that they drop their masks: it kills the play.

In a work of art the umbilical cord linking it with the totality of our concerns has not yet been severed, the blood of the mystery still circulates; the ends of the blood vessels vanish into the surrounding night and return from it full of dark fluid.

Nevertheless, if driven to give an exposition, he would say that the book presents a certain primitive, vitalistic view of the world in which matter is in a constant state of fermentation and germination. There is no such thing as dead matter, nor does matter remain in fixed form:

Reality takes on certain shapes merely for the sake of appearance, as a joke or form of play. One person is human, another is a cockroach, but shape does not penetrate essence, is only a role adopted for the moment, an outer skin soon to be shed…. [The] migration of forms is the essence of life.

Hence the “all-pervading aura of irony” in his world: “the bare fact of separate individual existence holds an irony, a hoax.”

For this vision of the world Schulz does not feel he has to give an eth-ical justification. Cinnamon Shops in particular operates at a “premoral” depth. “The role of art is to be a probe sunk into the nameless. The artist is an apparatus for registering processes in that deep stratum where value is formed.” At a personal level, however, he will concede that the stories emerge from and represent “my way of living, my personal fate,” a fate marked by “profound loneliness, isolation from the stuff of daily life.”

On the basis of his two books, preoccupied as they are with a child’s view of the world, Schulz is often thought of as a naive writer, a kind of urban folk artist. In his letters and essays, however, he emerges as a sophisticated intellectual who, despite being based in the provinces, can cross swords on terms of equality with confrères like Witkiewicz and Witold Gombrowicz.

In one exchange, Gombrowicz reports to Schulz a conversation with a stranger, a doctor’s wife, who tells him that in her opinion Schulz is “either a sick pervert or a poseur, but most probably a poseur.” Gombrowicz challenges Schulz to defend himself in print, adding that Schulz should regard the challenge as both substantive and aesthetic: he should find a tone that is neither haughty nor flippant nor labored nor solemn.

In his reply Schulz ignores the task Gombrowicz has set him, coming at the question instead from a slant. What is it in Gombrowicz and in artists in general, he asks, that takes secret delight in the most stupid, philistine expressions of public opinion? (Why, for example, did Gustave Flaubert spend months and years collecting bêtises, stupidities, and arranging them in his Dictionary of Received Opinions?) “Aren’t you astonished,” he asks Gombrowicz, “at [your] involuntary sympathy and solidarity with what at bottom is alien and hostile to you?”

Unacknowledged sympathy with mindless popular opinion, Schulz suggests, comes from atavistic modes of thinking embedded in all of us. When an ignorant stranger dismisses Schulz as a poseur, “a dark, inarticulate mob rises up in you [Gombrowicz], like a bear trained to the sound of a gypsy’s flute.” And this is because of the way the psyche itself is organized: as a multitude of overlapping subsystems, some more rational, some less so. Hence “the confusing, multitrack nature” of our thinking in general.

2.

Schulz is also commonly thought of as a disciple, an epigone, or even an imitator of his older contemporary Franz Kafka. The similarities between his personal history and Kafka’s are certainly remarkable. Both were born under Franz Joseph I into merchant-class Jewish families; both were sickly and found sexual relations difficult; both worked conscientiously at routine jobs; both died before their time, bequeathing troublesome literary estates. Furthermore, Schulz is (mistakenly) believed to have translated Kafka. Finally, Kafka wrote a story in which a man turned into an insect, while Schulz wrote stories in which a man turned not only into one insect after another but into a crustacean too.

Schulz’s comments on his art should make it clear how superficial these parallels are. His own inclination was toward the recreation, or perhaps fabulation, of a childhood consciousness, full of terror, obsession, and crazy glory; his metaphysics is a metaphysics of matter. Nothing of the kind is to be found in Kafka.

For Józefina Szelinå«ska’s translation of The Trial Schulz wrote an afterword that is notable for its perceptiveness and aphoristic power, but even more striking for its attempt to draw Kafka into the Schulzian orbit, in order to make of Kafka a Schulz avant la lettre.

“Kafka’s procedure, the creation of a doppelgänger or substitute reality, stands virtually without precedent,” writes Schulz:

Kafka sees the realistic surface of existence with unusual precision, he knows by heart, as it were, its code of gestures, all the external mechanics of events and situations, how they dovetail and interlace, but these to him are but a loose epidermis without roots, which he lifts off like a delicate membrane and fits onto his transcendental world, grafts onto his reality.

Though the procedure Schulz describes here does not go to the heart of Kafka, what he says is true and admirably put. But then he goes on:

[Kafka’s] attitude to reality is radically ironic, treacherous, profoundly ill-intentioned—the relationship of the prestidigitator to his raw material. He only simulates the attention to detail, the seriousness, and the elaborate precision of this reality in order to compromise it all the more thoroughly.

All of sudden Schulz has left the real Kafka behind and begun to describe another kind of artist, the artist he himself is or would like to be seen as. It is a measure of his confidence in his own powers that he could try to refashion Kafka in his own image.

The world that Schulz creates in his two books is remarkably unsullied by history. The Great War and the convulsions that followed upon it cast no backward shadow; there is no intimation that the sons of the barefoot peasant who, in the story “Dead Season,” is made fun of by the Jewish shop assistants will decades later ransack the same shop and beat the sons and daughters of the assistants.

There are hints that Schulz was aware that he could not forever live on the iron capital he had stored up in childhood. Describing his state of mind in a 1937 letter, he says that he feels as if he is being dragged out of a deep sleep:

The peculiarity and unusual nature of my inner processes sealed me off hermetically, made me insensitive, unreceptive to the world’s incursions. Now I am opening myself up to the world…. All would be well if it weren’t for [the] terror and inner shrinking, as if before a perilous venture that might lead God knows where.

The story in which he most clearly opens his face to the wider world and to historical time is “Spring.” Here the young narrator encounters his first stamp album. In this burning book, in the parade of images from lands whose existence he had never guessed at—Hyderabad, Tasmania, Nicaragua, Abracadabra—the fiery beauty of a world beyond Drohobycz suddenly reveals itself. And amid this magical plenitude he comes across the stamps of Austria, dominated by the image of Franz Joseph, emperor of prose (here the narrating voice cannot any longer pretend to be a child’s), a dried-up, dull man used to breathing the air of chanceries and police stations. What ignominy to come from a land with such a ruler! How much better to be a subject of the dashing Archduke Maximilian!

“Spring” is Schulz’s longest story, the one in which he makes the most concerted effort to develop a narrative line—in other words, to become a storyteller of a more conventional sort. Its plot concerns the quest of the young hero to track down his beloved Bianca (Bianca of the slim bare legs) in a world modeled on the stamp album. As narrative it is formulaic; after declining into a pastiche of costume drama it peters out.

But halfway through, as he is beginning to lose interest in the story he has concocted, Schulz turns his eyes inward and launches into a dense four-page meditation upon his own writing processes that one can only imagine as having been written in a trance, a piece of rhapsodic philosophizing that develops one last time the imagery of the subterranean bed from which myth draws its sacred powers. Come to the underground with me, he says, to the place of roots where words break down and return to their etymologies, the place of anamnesis. Then travel deeper down, to the very bottom, to “the dark foundations, among the Mothers,” the realm of unborn tales.

In these nether depths, which is the first tale to unfold its wings from the cocoon of sleep? It turns out to be one of the two foundation myths of his own spiritual being: the Erlkönig story, the story of the child whose parent has not the power to hold her (or him) back from the sweet persuasions of the dark—in other words, the story that, heard from his mother’s lips, announced to the young Bruno that his destiny would entail leaving the parental breast and entering the realms of night.

Schulz was incomparably gifted as an explorer of his own inner life, which is at the same time the recollected inner life of his childhood and his own creative workings. From the first comes the charm and freshness of his stories, from the second their intellectual power. But he was right in sensing that he would not forever be able to draw from this well. From somewhere he would have to renew the sources of his inspiration: the depression and sterility of the late 1930s may have stemmed precisely from a realization that his capital was exhausted. In the four stories we have that postdate Sanatorium, one of them written not in Polish but in German, there is no indication that such a renewal had yet occurred. Whether for his Messiah he succeeded in finding new sources we will probably—despite Ficowski’s optimistic wishes—never know.

Schulz was a gifted visual artist within a certain narrow technical and emotional range. The early Book of I dolatry series in particular is a record of a masochistic obsession: hunched, dwarflike men, among whom Schulz himself is recognizable, grovel at the feet of imperious girls with slim, bare legs.

Behind the narcissistic challenge of Schulz’s girls one can detect the example of Goya’s Naked Maja. The influence of the Expressionists is also strong, Edvard Munch in particular. There are strong hints of the Belgian Félicien Rops. Curiously, in view of the importance of dreams to Schulz’s fiction, there is no trace of the Surrealists in his drawings. Rather, as he matures, an element of sar-donic comedy grows stronger.

The girls in Schulz’s drawings are of a piece with Adela, the maid who rules the household in Cinnamon Street and reduces the narrator’s father to childishness by stretching out a leg and offering him a foot to worship. Fiction and artwork belong to the same universe; some of the drawings were meant to illustrate the stories. But Schulz never pretended that his visual art, with its restricted ambitions, was on a par with his writing.

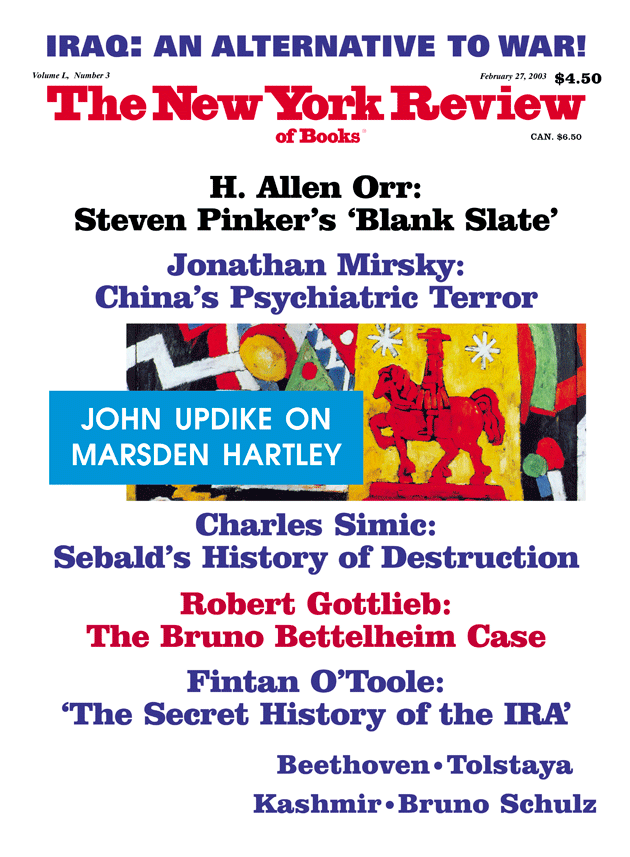

Ficowski’s book includes a selection of Schulz’s drawings and graphics. A fuller selection is available in the Collected Works of Bruno Schulz, edited by Ficowski and published in the UK by Picador, but alas not on sale in the US. All of Schulz’s surviving drawings are available in reproduction in a handsome bilingual volume published in 1992 by the Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature in Warsaw.

This Issue

February 27, 2003

-

*

A book of the kind that Schulz was planning has now been written by Henryk Grynberg: Penguin has recently issued a translation under the title Drohobycz, Drohobycz and Other Stories. Schulz himself figures as a minor character in the first of Grynberg’s stories. ↩