To the Editors:

Henry Siegman [“Israel: The Threat from Within,” NYR, February 26] simply, completely, does not understand the Middle East. How else explain his take on Hamas leader Sheikh Ahmad Yassin who, he said, had just offered to “postpone…’military’ operations in return for an Israeli withdrawal to its pre-1967 borders.” Siegman hailed this “change in [Hamas] policy,” even citing abstruse points of Jewish theology in support.

To say that Siegman is bamboozling his readers is the mother of all understatements. For decades, with commendable forthrightness and consistency, the leaders of Hamas and the Islamic Jihad have defined their goal as the destruction of Israel and its replacement with an Islamic Arab polity. (Palestinian Authority head Yasser Arafat has the same goal in mind and says as much either in code (publicly) or openly (when he believes he is not being taped).) The whole Arab world, with the Palestinians in the vanguard, continues to insist on Israel’s illegitimacy and to hope for its disappearance. The dispatch of droves of suicide bombers into Israeli cities, by the fundamentalist organizations and Arafat’s own “secular” Fatah, is merely the concrete manifestation, in microcosm, of this outlook.

What Yassin actually said (vide interview in Al Usbu’a, Cairo, January 19, 2004) was that his organization would suspend its attacks if Israel “ended the occupation…and [agreed] to the return of the Palestinian refugees to the homes from which they were expelled in the 1948 war and [agreed to] the establishment of a Palestinian state in the territories captured in 1967.”

There are several problems here. Surprisingly, even Siegman noticed one of them: Yassin had not promised an indefinite truce; he could, after graciously accepting the territories from Israel, renew at will the assault on Israel. He had not promised “peace.”

Secondly, Yassin had said nothing new. He had merely reiterated his agreement to a hudna (a temporary truce)—and this is sanctioned in Muslim theology (which is the theology Siegman should have been studying). It is all in the Koran. In 628, the Prophet Muhammad agreed to a year-long hudna, hudnat Hudeibiya, which he used to reorganize his forces and then, unilaterally, to break the truce and utterly destroy his erstwhile partners in nonbelligerency. This is exactly what Yassin is proposing vis-à-vis Israel, nothing more. (Arafat, incidentally, in a sermon in a mosque in Johannesburg back in 1994 had said the same thing about the Oslo accords—from his perspective, they were just another hudnat Hudeibiya.)

Lastly, Yassin had linked the suspension of hostilities to Israel’s acceptance of a mass refugee return. And as every (Palestinian) child knows (though perhaps not Siegman), a return of the refugees—almost four million are on the UN rolls—would instantly lead to anarchy and the destruction of the Jewish state, which is why the Palestinians, from Arafat and Yassin down, continue to insist on it, and why both Barak and Clinton rejected it back in the negotiations of 2000.

In his article, Siegman repeatedly “cited” things I had said—with a consistency of distortion that is truly mind-boggling. Just to give one key example: I most emphatically never stated anywhere that “the dismantling of Palestinian society…and the expulsion of 700,000 Palestinians [were] a deliberate and planned operation intended to ‘cleanse’…those parts of Palestine assigned to the Jews.” Quite the opposite. Had Siegman bothered to read my books, he would have discovered that mainstream (Haganah–JewishAgency) Zionist policy, until the end of March 1948—meaning during the first four months of the war—was to protect the Arab minority in the Jewish areas and to try to maintain peaceful coexistence. Intentions changed only in April, when the Yishuv was with its back to the wall, losing the battle for the roads and facing potentially politicidal and genocidal pan-Arab invasion. And even then, no systematic policy of expulsion was ever adopted or implemented (hence Israel’s one-million-strong Arab minority today). The Arabs have only themselves to blame for the (unexpected) results of the war that they launched with the aim of “ethnically cleansing” Palestine of the Jews. (Contemporary Arab apologists, always full of righteous indignation, conveniently forget this.)

And I did maintain, though the Ha’aretz interviewer Ari Shavit (unfairly) did not quote me in full, that had the 1948 war ended, in a demographic sense, more decisively, with either the Jews thrown into the sea or the Palestinians thrown completely into Transjordan, there establishing a state of their own (with all of Palestine west of the Jordan becoming Jewish), the Middle East would have enjoyed a far happier, quieter future, without much of the death and suffering we have witnessed since 1948. It is the demographically indecisive outcome of 1948, with the two populations still intermixed (and further intermixed by Israeli conquest and settlement of the territories since 1967), that has been one of the sources of continuing conflict. (This may not please liberal ears, but there have been cases in history of expulsions that, in the long term, have benefited both the expelling and expelled peoples (the mutual Greek and Turkish population “transfers” of the early 1920s being cases in point.)

Advertisement

I emphatically do not, as Siegman implies, support transfer (though I can foresee circumstances, in which Israel, attacked by the Arabs and (again) in existential, genocidal peril, might resort to similar actions). In present circumstances, transfer would be immoral and is in any case impractical. And I do not justify under any circumstances, murder, massacres, and rapes, as Siegman claims by (again) interweaving real quotes with his own syllogisms.

Benny Morris

Jerusalem

Henry Siegman replies:

I am criticized by Benny Morris for falsely attributing to him the view that, in 1948, leaders of the Yishuv, the Jewish settlement in Palestine, planned to expel—ethnically cleanse—Arabs in areas of Palestine assigned by the United Nations to the Jews.

Morris writes that he “most emphatically never stated anywhere,” as I said he did, that “the dismantling of Palestinian society …and the expulsion of 700,000 Palestinians [were] a deliberate and planned operation intended to ‘cleanse’…those parts of Palestine assigned to the Jews as a necessary precondition for the emergence of a Jewish state.”

Indeed, Morris claims that if I had bothered to read his books I would have known that “quite the opposite,” he has written that Zionist policy, until the end of March 1948 was to protect the Arab minority. And even after April of 1948, “no systematic policy of expulsion was ever adopted or implemented.”

The issue I addressed in my article is whether the mass exodus of 700,000 Palestinian Arabs from the areas in Palestine assigned to the Jews was the consequence of the chaos of war or whether it was “planned”—the result of a deliberate decision by Jewish leaders to expel Palestinian Arabs from these areas. The question I raised was whether—not when—such a decision was made (as to the question of when, I specifically quoted Morris’s statement that it was in April–May of 1948). Even after Morris’s first book on the subject, in which he reported that there were in fact deliberate expulsions of Palestinian Arabs, the Israeli version of what happened continued to be, for the most part, that Palestinian Arabs left on their own accord, despite the urgings of Jewish leadership that they stay.

I noted in my article that in the revised edition of Morris’s book, he writes that he found conclusive evidence that there was indeed a deliberate decision by Ben-Gurion to expel—the term “cleanse” is used extensively—700,000 Palestinian Arabs. Their flight was therefore not the unintended collateral damage of a war started by the Arabs but the result of decisions and actions taken by the Yishuv’s top political and military leaders.

Is this a “truly mind-boggling” distortion of Morris’s views? The following is Morris’s opening statement—word for word—to his interviewer, Ari Shavit, as reported in Ha’aretz of January 1, 2004:

What the new material shows is that there were far more Israeli acts of massacre than I had previously thought…. In the months of April–May 1948, units of the Haganah were given operational orders that stated explicitly that they were to uproot the villagers, expel them and destroy the villages themselves. [Emphasis added.]

The meaning of these words seems to be plain enough. But perhaps what Morris really meant in denying that he ever made such a statement “anywhere” is that he never referred to the expulsion of 700,000 Palestinians. The record, however, shows that he did.

Early in the interview, Shavit asked Morris whether he condemns the expulsions morally. His response: “No.” But “they perpetrated ethnic cleansing,” Shavit insists. “There are circumstances in history that justify ethnic cleansing,” was Morris’s reply. The alternative, he said, would have been the “annihilation” of the Jews.

“And was that the situation in 1948?” asked Shavit. “That was the situation,” Morris replied.

A Jewish state would not have come into being without the uprooting of 700,000 Palestinians. Therefore it was necessary to uproot them. There was no choice but to expel the population. It was necessary to cleanse the hinterland and cleanse the border areas and cleanse the main roads. It was necessary to cleanse the villages from which our convoys and our settlements were fired on.

Morris’s rationalization that had the Palestinians not been expelled, the entire Yishuv would have been “annihilated” is unconvincing. Morris knows very well that fellow New Historians—the Israeli revisionists of the received myths about Israel’s beginnings (of which Morris was considered a prominent member)—have established that the invading Arab forces were militarily inept and ill-equipped, and that the Yishuv prevailed because their forces were better organized, better equipped, and better commanded than the attacking Arab army. The notion that the Yishuv would have been annihilated had the Palestinian Arabs not been expelled is baseless.

Advertisement

Elsewhere in the interview, Morris callously explains the ethnic cleansing with the observation, “You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs. You have to dirty your hands.”

In the Ha’aretz interview, Morris describes a series of massacres and expulsions conducted by the Haganah:

In Operation Hiram there was an unusually high concentration of executions of people against a wall or next to a well in an orderly fashion. That can’t be chance. It’s a pattern. Apparently, various officers who took part in the operation understood that the expulsion order they received permitted them to do these deeds in order to encourage the population to take to the roads. The fact is that no one was punished for these acts of murder. Ben-Gurion silenced the matter. He covered up for the officers who did the massacres.

The interviewer asks, “What you are telling me here…is that in Operation Hiram there was a comprehensive and explicit expulsion order? Is that right?” Morris replies: “Yes” (emphasis added). Morris cites the name of the Haganah commander who issued the order “in writing” to his units to expedite the removal of the Arab population following a visit by Ben-Gurion to the Northern Command in Nazareth. Morris said that a similar expulsion order for the city of Lod was signed by another Haganah commander, also immediately after meeting with Ben-Gurion.

The interviewer persists: “Are you saying that Ben-Gurion was personally responsible for a deliberate and systematic policy of mass expulsion?” Reply:

From April 1948, Ben-Gurion is projecting a message of transfer. There is no explicit order of his in writing, there is no orderly comprehensive policy, but there is an atmosphere of [population] transfer…. The entire leadership understands that this is the idea. The officer corps understands what is required of them. Under Ben-Gurion, a consensus of transfer is created.

The disbelieving interviewer asks: “Ben-Gurion was a ‘transferist’?” Reply: “Of course. Ben-Gurion was a transferist. He understood that there could be no Jewish state with a large and hostile Arab minority in its midst.” The interviewer says to Morris, “I don’t hear you condemning him.” Morris replies, “Ben-Gurion was right. If he had not done what he did, a state would not have come into being. That has to be clear. It is impossible to evade it. Without the uprooting of the Palestinians, a Jewish state would not have arisen here.”

When such an unqualified conclusion is plainly stated, and its author then blandly insists it is something that he “most emphatically never stated anywhere,” there is reason to wonder if he has lost touch with reality.

Contrary to Morris’s assertion, I did not say in my article that Morris established that the Jewish leaders had a longstanding intention to expel Palestinian Arabs. Ironically, it is Morris himself who suggested this in an article that he wrote in The Guardian (January 14, 2004) following his interview in Ha’aretz. Morris wrote in the Guardian opinion piece that although there did not exist a master plan for the expulsion of Palestinian Arabs before April of 1948, “pre-1948 transfer thinking” by key Zionist leaders including Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann “had readied hearts and minds in the Jewish community [in Israel] for the dénouement of 1948. From April, most Jewish officers and officials acted as if transfer was the state’s desire, if not policy.”

As to my ignorance of Hamas and its real intentions, it is an ignorance apparently shared by Ephraim Halevy, who until recently served as the head of Sharon’s National Security Council and as his personal security consultant, and previously as head of the Mossad for four years. In a newspaper interview, also in Ha’aretz (September 4, 2003), Halevy said the following:

Hamas constitutes about a fifth of Palestinian society. Because they are an active, engaged, and aware group, they have more political weight. So anyone who thinks it is possible to ignore such a central element of Palestinian society is simply mistaken.

In my view, then, the strategy vis-à-vis Hamas should be one of brutal force against its terrorist aspect, while at the same time, signaling to its political and religious leadership that if they take a moderate approach and enter the fabric of the Palestinian establishment, we will not view that as a negative development. I think that in the end there will be no way around Hamas being a partner in the Palestinian government.

I think the conflict between Judaism and Islam is resolvable. There can’t be mutual acceptance, but I do see a prospect of achieving a historic hudna such as existed between Islam and Christianity for the past three hundred years.

By contrast, Morris believes, as he stated in his Ha’aretz interview, that not only Hamas, and not only all members of Palestinian society, but all Arab Muslims are “barbarians who want to take our lives.” He considers Palestinians “a very sick society” that should be treated “the way we treat serial killers.” He adds that “until the medicine [to cure their illness] is found they have to be contained so that they will not succeed in murdering us.” When asked by Shavit how this could be done, Morris replied, “Something like a cage has to be built for them.”

Morris suggests I should have studied Islamic theology rather than Jewish theology. While I am not entirely unfamiliar with Islamic theology, I think Morris would have benefited from a greater familiarity with Jewish theology. Despite Morris’s demonization of Islam, both in its formative stages and today, normative Judaism, including its greatest philosophers and scholars (particularly Maimonides and the Me’iri) considered Islam—far more so than Christianity—a truly monotheistic faith that serves the purpose of universalizing Judaism’s essential message. They hardly could have entertained such a view if they saw Islam as Morris does—as a murderous scourge on mankind.

To justify his demonizing of the Palestinians, Morris points to their continuing belief that, by virtue of their residence in Palestine for more than a thousand years, their claim to patrimony in all of Palestine is deeply rooted and takes precedence over the Jewish claim. Morris believes this is evidence that Palestinians will never agree to the historical primacy of the Jewish claim in any part of Palestine over their own. Morris is right. But he is dead wrong in the conclusion he draws from this, namely that it is a belief that precludes a Palestinian acceptance of Israel’s right to exist.

Why this is so should have been obvious to Morris and to the many Israelis who misconstrue the consequences of this belief exactly as Morris does. The obviousness stems from the parallel belief among many Jews that all of Palestine is rightfully their patrimony. Would Israelis agree to a Palestinian demand that they abandon this belief as a condition for a peace agreement that recognizes Palestinian statehood in parts of the West Bank? Would Palestinians be justified in concluding from a Jewish refusal to make any such formal disavowal that Jews are deceitful and harbor a secret plan to destroy a new Palestinian state? The answer should be self-evident. No one can demand of either Palestinians or Jews that they renounce highly subjective claims shaped by their respective historical and religious narratives. But each side has a right to demand of the other that it accept practical arrangements that will enable both to live in peace.

Sadly, when Morris turns from his historical research to expound personal views on politics and morals, he sounds not much different from the racists and xenophobes among the Islamic fanatics that inflame his imagination .

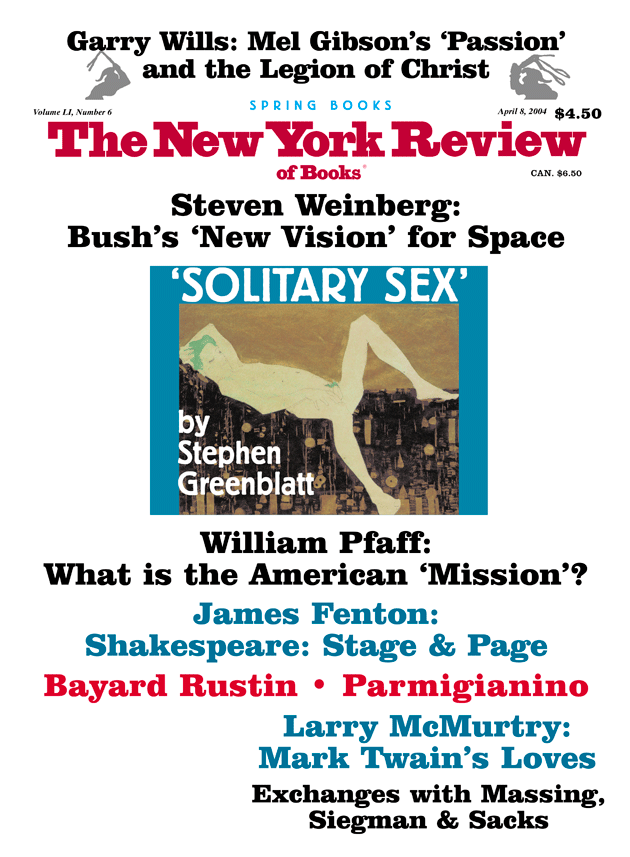

This Issue

April 8, 2004