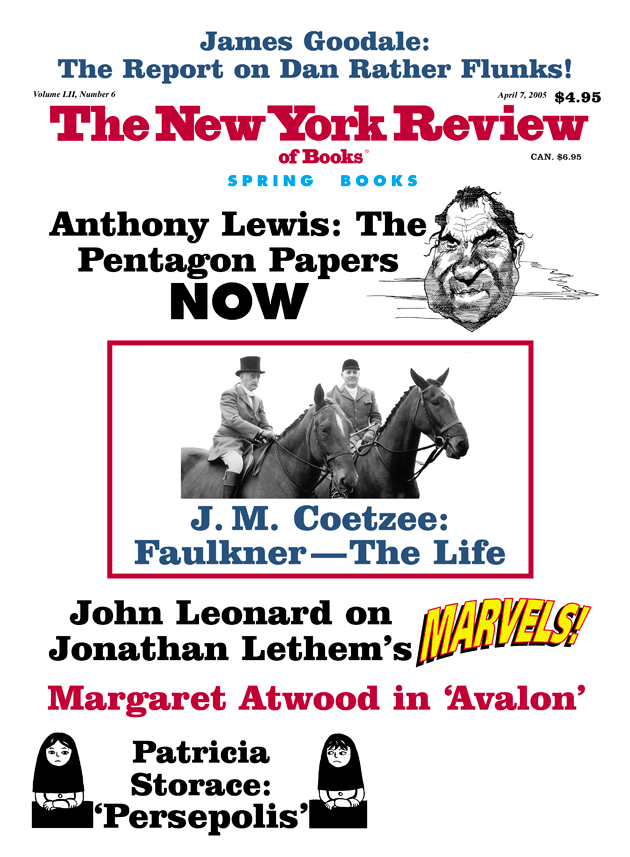

1.

The two volumes of Persepolis, the implacably witty and fearless “graphic memoir” of the Iranian illustrator Marjane Satrapi, relate through an inseparable fusion of cartoon images and verbal narrative the story of a privileged young girl’s childhood experience of Iran’s revolution of 1979, its eight-year war with Iraq, her exile to Austria during her high school years, and her subsequent experience as a university student, young artist, and wife in Tehran after her return to Iran from Europe in 1998. That Persepolis 1, a book in which it is almost impossible to find an image distinguished enough to consider an independent piece of visual art, and equally difficult to find a sentence which in itself surpasses the serviceable, emerges as a work so fresh, absorbing, and memorable is an extraordinary achievement.

In the cartoon world she creates, pictures function less as illustration than as records of action, a kind of visual journalism. On the other hand, dialogue and description, changing unpredictably in visual style and placement on the page within its balloons, advance frame by frame like the verbal equivalent of a movie. Either element would be quite useless without the other; like a pair of dancing partners, Satrapi’s text and images comment on each other, enhance each other, challenge, question, and reveal each other. It is not too fanciful to say that Satrapi, reading from right to left in her native Farsi, and from left to right in French, the language of her education, in which she wrote Persepolis, has found the precise medium to explore her double cultural heritage.

She is a rare kind of artist, one who makes use not only of her talents, but a disciplined, deliberate use of her imperfections as a verbal and visual stylist, not attempting to conceal them, but to incorporate them as part of her subject. In Volume 2, in a chapter called “The Socks,” there is a poignant, absurd, and enraging sequence that explains the source of the odd truncation and awkward gestures of Satrapi’s images, particularly of bodies. The art department of her university in Tehran, under the supervision of mullahs, was forbidden to offer traditional anatomy classes. Female models posed covered head to toe in sheets like black chadors, while male models were allowed to pose in marginally more revealing street clothes. When Satrapi, an indefatigable student, stays late to draw a seated male model, she is challenged by a supervisor, who tells her it is against the moral code for her to look at the man she is drawing. When she asks with incredulous flippancy if she should look instead at the door while drawing the man, the supervisor replies, “Yes.”

Satrapi herself has said in an interview, “There were many things I didn’t do because I couldn’t do them. But I was clever enough to take my lack and make a style of it.” It is precisely this quality of inventive limitation, the visible struggle with the accidents of restriction, of fruitful disillusionment, that makes Persepolis such a winning, rueful, and effective autobiography, the story of the creation of a person, of a way of being in the world, partly shaped by heritage, partly at odds with it.

Persepolis renders human actions, ideas, and feelings as having the vitality, quality of apprenticeship, and crudity of cartoons. As cartoons, we see the world in what we do not recognize is our own style, confined in frames we are unaware of; gods, rulers, and lovers appear to us, at least in part, as our own creations. Persepolis, with its narrow range of styl-ized cartoon gestures and expressions, obliquely makes the orthodoxies Satrapi encounters—the “divinely chosen” monarchy of the Shah, as Iranian schoolbooks of the period declared, the Islamic theocracy that replaces him, the smugly xenophobic Catholicism she confronts in her Austrian school years—seem presumptuous. How can creatures pretend to know God with such detail and confidence when they are still in search of their own characters, when they can know so little of themselves?

Volume 1 of Persepolis opens with a black-and-white image evoking a grammar school camera portrait of Marjane Satrapi in Tehran in 1980, at the age of ten, her hair covered with the black veil it is now obligatory for girls to wear at school. Whether or not Satrapi recognized it at the time, the history and character of her family made her a uniquely well-placed witness to the wrenching instability of her country’s political odyssey, a saga her father describes as “2500 years of tyranny and submission,” in which her own family underwent great reversals of fortune.

Satrapi was born into an aristocratic family, a great-granddaughter of the Qajar dynasty Shah who was overthrown in 1927 in a British-sponsored coup by a soldier who became Reza Shah, the father of the Shah who would in turn be exiled in 1979. Reza Shah confiscated the land and personal fortune of Satrapi’s grandfather, as he notoriously did the holdings of a number of other powerful and wealthy families when he came to power. Satrapi’s grandfather also served as a prime minister under Reza Shah. When he later became a Communist, the Shah periodically imprisoned him; during his detention he was tortured. Satrapi’s father’s family were also active on the left. An uncle and other relatives were involved in the creation of a short-lived independent republic in Iranian Azerbaijan, a coup crushed by the Shah. Members of her family’s circle were imprisoned under the Shah, freed, and again imprisoned under Khomeini. A beloved uncle was executed by the Islamists as a “Communist spy,” his own uncle having been earlier executed by the Shah. Satrapi’s favorite childhood reading, she tells us, was “a comic book entitled ‘Dialectic Materialism,'” while her mother’s favorite was Simone de Beauvoir’s The Mandarins.

Advertisement

Satrapi’s family was distinguished not only by its aristocratic background and tradition of dissenting political activism, but in the environment created by the devoted partnership of her parents, a marriage rare by the standards of any culture, but even more extraordinary in a setting where family custom and law itself still define women as men’s inferiors, where as one of Satrapi’s friends says with bitter humor, a mother’s pet name for a son is “doudoul tala, golden penis.” Marjane was as beloved as if she were a son, and her education and ambitions taken as seriously as a boy’s; in contrast to the social and political chaos outside, Satrapi’s home sheltered an enviable society, a place of freedom, profound affection, learning, trust, and outspoken discussion. The forthright honesty her family nurtures in her becomes both a source of predictable endangerment and a source of unpredictable salvation.

In a hilarious and taboo-breaking sequence in Persepolis, Marjane’s parents and grandmother respond with admiring sang-froid to her declared ambition at the age of six to become the “Last Prophet” and found a new religion, which she symbolizes by drawing herself as a popular Iranian mythological image, Khorshid Khanoum, the Sun Lady, whose head is surrounded with rays. In Satrapi’s drawing, followers kneel at her feet, addressing her with comical reverence as “Celestial Light.” “I am the Last Prophet,” declares the child in the next panel to a group of bearded prophets, including Jesus, who collectively exclaim in response, “A woman?,” though no one seems to hesitate because she is a child, or worry about her appetite for hearing her own praise. This clear-eyed and not untender scrutiny of worldly ambition mixed with dreams of grandiose messianic mission prevents the sequence from being arch, negligible, or even irreverent. In showing a child’s genuine wish for the power to do good, Satrapi does not ignore her own ambition for the last word, for authority and adulation, for disciples who murmur epithets in her praise. She eyes herself as keenly as—more keenly than—the clubby guild of male prophets whose only response is to be aghast that a female claims to represent God, to be their moral equal before God. Satrapi presents the messianic ambition as human, belonging to men and women, adults and children, an impulse shared by both the worldly and unworldly.

When Marjane writes a “holy book,” her eighth rule, inspired by her indomitable, beloved grandmother, who suffers from arthritic pains, is that it will be forbidden for old people to suffer. “In that case,” says her grandmother, “I’ll be your first disciple.” Marjane, who wants to be “Justice, Love and the Wrath of God all in one,” has intimate, occasionally imperious conversations with a white-bearded God. “You think I look like Marx?” he asks her over a companionable glass of milk.

It is not toward the idea of God that Satrapi is irreverent; it is toward a too credulous approach to the ambiguities of human motives and the temptations of moral aspiration. She sees how religious faith may serve as an exemption or protection from the discipline of self-knowledge, can function as a way of freeing a person from the work of moral inquiry, and create an environment in which a person’s will and desires are so identified with the divine that he feels anything is permitted to him. Satrapi is the moral equivalent of an insomniac; she allows herself no moral repose. In a powerful and funny moment, after a conversation with her mother about the need to forgive people who had done harm in the service of the previous regime, Satrapi draws herself making speeches about forgiveness to a mirror, rapt in the image of her own invincible goodness. Satrapi may very well be a believer in God; it is above all toward herself that she is an agnostic.

Advertisement

The household her parents create, which manages to be both visionary and secure in its traditions, is, however, surrounded by a society they did not create. Even though her parents encourage her to explore the limits of her moral imagination and powers, Marjane painfully discovers the limits of their powers, overmatched by the entrenched Iranian class system.

Although Marjane grows up reading the novels of Ashraf Darvishian, “a kind of local Charles Dickens,” whose books describe the suffering of Iranian children from poor families, who work as porters, carpet weavers, and even three-year-old windshield washers, the Satrapi family itself employs a child maid, Mehri, who “was eight years old when she had to leave her parents’ home to come to work for us.”

Mehri, ten years old when Marjane is born, acts as her caretaker and companion. “Like most peasants, she didn’t know how to read and write,” though Marjane’s mother makes failed efforts to teach her. At sixteen, Mehri falls into a dreamy fantasy romance with a boy who lives in the apartment building opposite. She and the boy begin to correspond, with Marjane acting as Cyrano de Bergerac, writing love letters which Mehri signs, and reading Hossein’s letters aloud to her. Mehri poses in the letters as Marjane’s sister, until her own younger sister, who works for Marjane’s uncle, discovers the romance, and in a fit of jealousy, discloses Mehri’s and Hossein’s flirtation. The boy’s ardor cools as soon as he learns that Mehri is not Marjane’s sister, but a maid, and he instantly relinquishes her letters, all written in Marjane’s hand, to Marjane’s father. He gently explains to his shocked daughter that “their love was impossible” because “in this country you must stay within your own social class.” The child crawls into the heartbroken teenage maid’s bed to comfort her, but for the first time she has seen a way in which her father himself is helpless, powerless to extend to another child the privilege and protection he offers her.

She will have an even more shattering later encounter with the intact Iranian class system under the Islamic regime, during the Iran–Iraq war, when she is an adolescent. Another family maid’s fourteen-year-old son has been recruited, like the other boys in his school, and given a plastic, gold-painted key, which will unlock the gate of paradise for those “lucky enough to die” in battle. Marjane asks her own fourteen-year-old cousin if at his school boys are given the keys to paradise, but he has never heard of them. When Marjane’s mother offers to talk to the maid’s boy about the real cost of “martyrdom,” inviting him to imagine the future life he might want for himself, he points innocently to Marjane and says, “I’ll marry her,” which earns him a reproving slap from his mother for his presumption.

In one of her most effective juxtapositions of images, Satrapi draws the sons of the poor, as they are flung into the air by exploding mines, keys swerving around their necks as their bodies turn into shadows on the page, while the panel below shows children at Marjane’s first party, dressed with the aestheticized violence of punk fashion, wearing necklaces of chains and nails, their bodies, too, flung orgiastically into the air, dancing to imported punk rock in an explosion of adolescence.

2.

The opening page of Persepolis with its five frames is a model of the wonderful swiftness, economy, nuance, and wit with which Satrapi handles her complex narrative. Having begun the story with a self-portrait, the prism through which the events of the story will be experienced, Satrapi multiplies the veiled girl’s face, so that it expands into a class group portrait, each little girl identically veiled and posed with folded hands, but each child’s face involuntarily exhibiting a range of characteristics and responses—sullen, bored, eager to please, disdainful. If the veil is meant to control and define how these children may act, it has failed at the outset. It is impossible to veil their characters.

The next two frames in the sequence brilliantly juxtapose an image of the 1979 revolution with an image of its result, unintended and unexpected by many of the disparate secular political groups who supported the deposition of the Shah. Satrapi reminds us of that through her caption, which reads, “In 1979 a revolution took place. It was later called ‘The Islamic Revolution.'” Her first image of the revolution is a sea of white faces set against a black background, men and unveiled women standing together, with their fists raised in protest. In the next panel, post-revolution, the black background has become white, and a woman with a severe expression, wearing a full black chador, peremptorily orders “Wear this!” and distributes to each unveiled schoolgirl a black cloth that looks like the covering dropped over birdcages to silence songbirds. Through her imperious gesture, and domineering smirk, Satrapi conveys the teacher’s pleasure in the girls’ submission; with this image, she swiftly establishes that the insistence on the veil can come from women as well as men. Satrapi reminds us of this forcefully a few panels later, with an image of veiled and unveiled women shaking their fists at each other, demonstrating for and against wearing the veil. And through the device of her changing patterns of black and white, Satrapi dramatizes the unpredictability of events; this image of segregation, dominance, and submission is not what the defiant crowd of men and women in the previous panel might have foreseen. They have risked themselves to challenge one power, miscalculated, and have found themselves in the grip of another.

The fifth and largest frame on the opening page is a scene in the school courtyard of these ungovernable schoolgirls making their new veils into toys. These vignettes serve as metaphors of the many ways the veil itself can be shaped into a form of personal expression. In a scattering of visual anecdotes, one girl covers her face completely, pretending to be a monster, another uses hers as a bridle for an imaginary horse, a third uses hers as an impromptu jump rope. In one chilling image, a little girl plays a darker game, pretending to strangle another, shouting “Execution in the name of freedom,” with the combination of prideful, self-justified violence and formulaic moralizing rhetoric that is the lingua franca everywhere of corruption.

Satrapi, like many comics artists, builds a vocabulary of imagery, and this little girl’s facial expression is an important part of her treasury. We meet this murderous frown again, in both volumes of Persepolis, on the faces of children, women, and men, Muslims and Christians. It is the expression on an elderly Austrian man’s face shouting at Marjane in the Vienna metro, “Dirty foreigner, get out!” It is the expression on the face of an Iranian woman “Guardian of the Revolution” as she threatens the teenage Marjane on a Tehran street, snarling “Lower your scarf, you little whore.” It is the expression of a bearded member of a death squad, who, not finding his intended victim, a Communist intellectual, at home, strangles his sister in the name of “divine justice.” And it is the expression on young Marjane’s own face, as she and some other children whose parents supported the revolution set out with improvised weapons made of nails, to attack a boy whose father was rumored to have been a member of the Shah’s notorious secret police. “In the name of the dead,” Marjane exhorts the other children, “we’ll teach Ramin a good lesson,” a revenge her mother prevents in time.

In Satrapi’s work, there are equalities so powerful that they transcend the proscriptions of social convention, age, sex, nationality, the will of law and theology itself. One of these is the shared capacity for cruelty. Another is human vulnerability, brought home to the young Marjane when two of her parents’ friends, released from the Shah’s prisons, in the unguarded joy of their reunion describe the tortures the prisoners suffered, including being burned by heated irons. (One of these friends would be executed by a death squad under the Islamists; the other, destined for the same fate, escapes from the country “hidden among a flock of sheep.”)

Marjane draws herself round-eyed with fear and suspicion, shrinking from the family’s laundry room, never having imagined the iron as anything but a bringer of domestic order, wielded by women. And through her father’s account of the fate of the political detainees, “who constituted our country’s intelligentsia,” executed in the Islamic regime’s prisons shortly before the armistice of the Iran–Iraq war, she grasps the ultimate and most incontrovertible of equalities, that of mortality. Her drawing of this scene represents men and veiled women before a firing squad, falling to the ground in rows. In this scene, the men too wear a kind of veil, the blindfold that shields the executioners from looking into the eyes of the people they are killing.

Even passionate sincerity and goodness offer no protection, Marjane agonizingly discovers, when her gentle Uncle Anoosh, a Communist who believes in social justice with a mystic’s reverence (and for whom the little Marjane is a cherished surrogate daughter), having survived the Shah’s prisons, is executed in a prison of the new regime.

Satrapi’s portrait of post-Khomeini Iran is of a state that, like an abusive parent, is dangerously, capriciously, and violatingly intimate with the bodies of its citizens. They are newly insulted and threatened by armed guards for wearing ties or sneakers, or not wearing veils, lashed with whips for having parties and chess sets. They are examined with minute and prurient interest by strangers, as when in Volume 2, Satrapi is instructed by two guards through loudspeakers to stop running as she tries to catch a bus, because running, they explain, causes her behind to make “obscene” movements. Ever uncompromising, Marjane shouts “Well then don’t look at my ass!” In a state in which religious belief is accorded political, social, and economic advantage, ambitious piety instantly creates a whole new range of sins, of discrimination, falsehood, double-dealing, and competitive power struggles expressed through metaphors of devotion. “I pray five times a day,” boasts a nouveau-Islamist teenager to Marjane, who trumps him by declaring that she prays ten or eleven, sometimes twelve times daily. She is perpetually narrowly escaping serious trouble, rebelliously outspoken as if she is trying to outpace a hypocrisy she is afraid is about to overtake her.

The years between 1980 and 1983 were particularly dangerous for young people. The regime did not hesitate to imprison and execute both college and high school students, forcing condemned girls to be married to, then raped by, guards before their executions, since it is against the law to kill a virgin. When Marjane is expelled from her school after a tussle with the principal, who is trying to confiscate her jewelry, her parents conclude that the risk of sending her abroad alone is less dangerous for her than staying home. They arrange for her to go to school in Vienna, boarding with Iranian émigré friends.

In the final panel of Volume 1, Marjane’s mother, whose manner has been impeccably cheerful and tranquil during their goodbyes, faints in the airport after Marjane has passed through customs to board her flight. The image is a daring one, unmistakably based on the Pietà, this time with a man, Marjane’s father, portrayed as the sustaining mourner, with the woman in the posture of Christ. Until this culminating image, Satrapi’s drawings have had some of the qualities of illustrations for children’s books, which is an important source of their power, as these naively and whimsically drawn beings are caught in a world of war and revolution, the events of the story in wrenching conflict with the style in which is it drawn.

Her style in Volume 1 is faintly reminiscent of Bemelmans’ in his Madeline books, though the figure of benevolent nun Miss Clavel is transformed into grimly authoritarian chador-wearing schoolteachers and morals patrol squads. Bemelmans’ little Parisian girls are dressed in uniforms because they are being well brought up and protected, while the costumes of the little girls in Persepolis have become a matter of life and death. Both Satrapi and Bemelmans draw the world as toylike, with a deliberate, stylized childish charm; their figures, both adults and children, are doll-like, though in each, the figures of children are more poignant and alive, because they are drawn like toys come to life, their miniature bodies animated by passionate gestures and postures, by a full-scale emotional life they are as yet safely powerless to live. In Bemelmans, and in many other children’s book illustrators, this style promises that wishes are granted, that experience is a form of play, that the characters will not come to any real harm, whatever their adventures. Satrapi uses this style, which offers a benevolent, trustworthy world, like a fresco in a nursery, and matter-of-factly breaks our hearts with it, creating a confrontation between what is drawn as adorable with a world that does not requite its claims to protection, hope, or love.

Fittingly, Satrapi’s style in Volume 2 is more adult, and more assured as well. In Volume 1, Satrapi’s panels tended to move almost exclusively from face to face. In Volume 2, there is more variety of architecture and décor, more of the drama of physical interaction, and as in the work of Félix Vallotton, clearly an influence, Satrapi is engaged in an intense exploration of pattern. Through the changing relationships of shapes, facial expressions, costumes, and dialogues of light and dark, she explores the patterns of human behavior, Eastern and Western culture, of history and incident.

Volume 2 opens with a menace from a new kind of veiled woman, the nuns who run the Vienna boarding house into which the newly arrived Marjane, alone for the first time and speaking no German, is unceremoniously dumped by the Iranian émigré woman who had promised to house her while she attends the French lycée. When the hostile Mother Superior insults Marjane by telling her it is a fact that “all Iranians are uneducated,” Marjane is expelled from the house for replying that in that case, it must be a fact that all nuns were once prostitutes. To justify ridding herself of the young girl, the Mother Superior informs Marjane’s parents, in an outright lie, that she was expelled for stealing a fruit yogurt. It is the first incident of what will be the adolescent Marjane’s signal experience of the West, a series of abandonments, of shallow romances and relationships that are based on sheer emotional and material expedience, relieved by temporary kindnesses.

Marjane finds herself caught up in a world where people momentarily crave and use each other like the products in their dazzlingly crammed shops. For her, the exhibitionistic, compulsive casual sex of her high school peers is shocking, as are their indifferent displays of nakedness; they lack a sense of physical individuality, of personal physical reality and self-respect. This imposes its own iron uniformity on their sexuality, their nudity a Western version of the chador.

Nor can she find a place in a world in which being Iranian is a stigma, and “Iran was the epitome of evil.” Vienna forces Marjane into a perpetual search for shelter, like a woodcutter’s child in a fairy tale. She does indeed end up lodging with a kind of witch, who insults her repeatedly for being Iranian, then torments her by allowing her pet dog to defecate on Marjane’s bed, and later falsely accuses her of prostitution and theft. As in many Teutonic folk tales and poems Marjane ends up nearly dying homeless in the snow. A society in which no one can muster an adult’s concern for a lonely foreign adolescent is no refuge for Marjane, used to an Iran in which “every arriving passenger was…met by a dozen people.” Baccalaureate in hand, now eighteen, she returns to what is still her home. She has not been able to be free in either West or East, and her return has the air of a kind of quest for a freedom that has eluded her in both countries.

The Iran she returns to is profoundly scarred by eight years of a war now thought a purposeless slaughter by her father, among others, in which now at “least one street in three [in Tehran] is named after a martyr,” and a reunion with a close childhood friend means accustoming herself to him not only as a grown man, but as a war-wounded paraplegic. Forty percent of places at the university are reserved for the “children of martyrs” and the war-disabled. Marjane, after a difficult adjustment to social restrictions that she finds even more chafing after her years in the West, wins a place at the university, partly through qualifying for the art department with a shrewd recasting of the Pietà, this time drawn as an Iranian soldier with his chador-wearing mother, flanked by the red tulips said to grow from the blood of martyrs.

Even armed with an academic acceptance, she must now undergo an “ideological” test, in which she is examined on her religious belief and practice. Although Marjane, with her characteristic outspokenness, questions the wearing of the veil and the necessity for praying in Arabic when her native tongue is Farsi, the mullah who interviews her turns out to be a man with a breadth of religious sensibility; used to extravagant protestations of faith, he finds her honesty reverent, even irresistible. Later, after Marjane gives a daring speech criticizing new dress restrictions as not only physically but academically hampering for art students, he invites her to design a uniform that will allow the students to use their brushes and clays freely.

Marjane, even though she is deeply Iranian, does not know how to live in her own country. Partly through temperament, partly through having spent her adolescence in Austria, partly because manners, gestures, social codes and their interpretations change, she repeatedly fails to gauge social nuance. In one bravely told anecdote, Marjane, fearing that she is going to be picked up for wearing lipstick by “Guardians of the Revolution” in one of their periodic raids, incriminates an innocent bystander to save herself. She diverts the Guardian’s attention by claiming that a man nearby made an “indecent” remark to her. He is hauled into their van, and taken to their headquarters. When she asks her boyfriend to reassure her that nothing serious will happen to the man, he cannot; it depends on the caprice of the Guardians. He may be, according to their mood, beaten, fined heavily, whipped, maimed, or even hanged. Even so, Marjane does not fully grasp what she may have done until she jokingly relates her adventure to her grandmother. Seeing her grandmother’s anger and disgust changes Marjane’s view of what she has done. For her, the most effective government is the judgment of someone she loves and respects, which alters, subtly and permanently, how she governs herself.

Part of Marjane’s path to comprehension in Iran is to learn to take her own perceptions skeptically, to lose faith in them. Critical of her peers, who are made up to look like “the heroines of American TV series,” she feels isolated and disapproving of their trivial preoccupations as she sees them. But what would have been frivolous in Vienna is in Tehran an assertion of freedom, though she also learns that often, that claim to freedom is itself limited, when she loses the friendship of half her university class for her candid admission that she has a full sexual relationship with her boyfriend.

Iran, she finds, forces a double life on everyone: “Our behavior in public and our behavior in private were polar opposites…this disparity made us schizophrenic.” And to ease the strain, Marjane and her peers, by day forbidden even to share the same staircase at the university, drink and dance together at parties nearly every night, a practice that sets them on a regular cycle of being arrested in raids, and being bailed out thanks to the fines their parents pay. “To be able to party,” Satrapi writes, “you had to have means.”

In a brilliant narrative sequence, Satrapi shows how one of these parties ends tragically. To convey the foreboding and terror of this raid, Satrapi draws for three pages without using any words or dialogue, the cartoonist’s equivalent of silence in a film. She shows us the arrival of the Guardian patrol, who spy on the apartment building with binoculars, discovering a party of young people in Western dress, glasses in hand. There is a frenzied effort to direct the boys to the roof to hide, pour the contents of the bottles into the toilet, hurriedly put on Islamic dress. But this time, a guard menaces the hostess with a rifle, and unexpectedly the troop gives chase to the boys, who begin to leap from rooftop to rooftop to escape them. One boy’s leap fails, and he falls from a building roof, clutching at the new moon, a consummate symbol both of what cannot save him and the life he could not and will never have.

Eventually, Marjane and her boyfriend are forced to marry, simply to be able to see each other freely. For their final project as art students, they are asked to design a theme park based on Iranian mythology. Although they earn a perfect grade, and are urged to present the project to the mayor of Tehran, the mayor kills the proposal. The female figures of Iranian mythology cannot be presented riding on the backs of animals without being covered head to toe. In Satrapi’s Iran, one is forbidden to be truly and fully Iranian. Eventually, “not having been able to build anything in my own country,” she emigrates permanently to France.

That sense of failure constitutes the only falsehood in a resolutely honest pair of books. Satrapi has surely built something both inside and outside her country with Persepolis.* She communicates both the richness and self-destructiveness of Iranian culture. The double life Iran has forced on her has made her neither a cynic nor an idealist, neither an atheist nor a fanatic. No Molly Bloom, she says both no to the world and yes, with the shifting proportions of dissent and assent of a genuine artist.

This Issue

April 7, 2005

-

*

Although Satrapi has said there will be no third volume of Persepolis, she continues to challenge received ideas about Iran with Embroideries, a ribald and irreverent cartoon account of relations between Iranian men and women. ↩