1.

Ever since I finished writing a life of Henri Matisse,1 I have been haunted by an image from H.G. Wells’s novel The Invisible Man. The hero of that book invents a scientific process to make himself invisible with no means of reversing the effect so that he finds himself trapped, unable to establish his identity, or prevent the public from picturing him as an almost mythical fiend stalking the streets. He ends up on the run, hunted, cornered, and finally bludgeoned to death, at which point the horrified crowd watches the invisible monster created by panic and mass hysteria slowly take shape in the gutter in front of their eyes as, in reality, an emaciated, bruised, and battered naked body.

This image—of a defenseless human being hounded and brought down by ruthless pursuers—corresponds fairly closely to the French view of biography, a view forcibly expressed by Louis Aragon in his infuriating Matisse: A Novel. This is an elaborate firsthand account in two volumes, published seventeen years after its subject’s death in 1954, and described by its author as a work of imagination, “not mine but the painter’s.” Aragon saw it as the duty of people like himself, who knew Matisse, to conceal or destroy anything that might cast light on the painter’s private life. “We, the last of his contemporaries, we didn’t force him to rip off his shirt and bare his heart…,” Aragon explained, emphasizing in a postscript his invincible contempt for the role of biographer: “We didn’t challenge him to say the unsayable, we didn’t subject him to the sort of crude blackmail common to every sort of investigative inquiry today.”

In what the French call the Anglo-Saxon world, the great foundation stone on which all subsequent serious study has been built is Matisse: His Art and His Public, a uniquely rich and comprehensive survey of documentary evidence compiled for the Museum of Modern Art by Alfred Barr in 1951. Barr’s book (never, incidentally, translated into French) became my guide, mentor, and road map. But the general consensus, freely expressed by experts in public and private, saw Matisse as drab, tame, and stuffily conventional, with a shrewd grasp of business but little intellectual or emotional depth. There had never been a biography, I was told by a leading scholar, because—in case I wondered why—“Matisse’s life would be too dull to write about.”

Failing any more specific directions, I turned to Matisse himself. His instructions on how to produce a portrait—as applicable in literary as in pictorial terms—were lucid, pertinent, and precise. He insisted on meticulous accuracy while maintaining that close study of external detail can never supply more than the starting point for a portrait. Success or failure at a deeper level was a matter of contemplation, concentration, the force and quality of attention focused on any given subject. Subtlety of observation counted for more than anything else. Matisse said that nothing should be distorted or suppressed. Approximations did not interest him. Anyone setting out to make a portrait must above all approach his or her subject without preconceptions.

Anglo-Saxon pragmatism dismissed the life as banal, if not actually discreditable. On balance I preferred the French Cartesian approach, which unequivocally ruled out consideration of anything except the work. Aragon pictured Matisse’s canvases as a great wall erected between him and us. Nothing more could—or should—be found out. (“We shall never know anything more about him. Or, if anyone pretends to, I deny it”: it would be impossible to count the number of times people have repeated variations on that formula to me over the past decade and more in France.)

This is an admirable theory. The problem, in practice, was that the pure, undefiled, blank page of Matisse’s life had filled up over the years with inaccuracy, distortion, and myth, all continually repeated in versions that grew steadily blander and more blurred. My plan was to apply the painter’s methods to his life, discarding the kind of prejudice which Matisse said was to the mind what visual cliché is to the eye. I was trying to follow his own rule of thumb:

To sum up, I work without a theory. I am conscious above all of the forces involved, and find myself driven forward by an idea that I can really only grasp bit by bit as it grows with the picture.

Starting out with no clear sense of what you are looking for can bring unexpected results. Wells’s invisible man had to put on a suit if he wanted other people to know he was there. Matisse seems to have done the same for the opposite reason. His most ambitious early self-portrait, painted in 1906, is painfully exposed, full of raw emotions (anxiety, rage, frustration) that make him instantly recognizable as the crackpot whose canvases looked to contemporaries like the work of a wild beast. The public image he conveyed in interviews and photographs was more guarded. He looks ponderous and buttoned-up in publicity handouts, nearly always tightly encased in the sort of suit that made strangers take him for a businessman or somebody selling insurance.

Advertisement

After a while I began to suspect that this last was, metaphorically speaking, exactly what he was doing. Matisse disliked being photographed or questioned by people he didn’t know, many of whom thought he was mad. In later years, young admirers, who put him on a pedestal, made him feel even more uncomfortable. Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, he kept an elderly best suit of reddish tweed which he put on, even in the stifling heat of August in Paris or Nice, for encounters with unknown, intimidating, possibly overbearing visitors (especially upper-class English or American women whose language he didn’t speak). In order to understand why, we have to go back to the moment when he first deliberately disguised himself in a suit.

By the start of the twentieth century Matisse was well on the way to inventing a new, disturbing, and at that stage virtually incomprehensible visual language. He was a familiar figure, loping about the streets of Montparnasse in a black sheepskin coat turned wrong side out—some said it looked more like a wolfskin—clutching a roll of crazy paintings no other artist could make head or tail of. But almost from one day to the next Matisse drew back from the brink of modernity and started turning out relatively conventional figure and flower pieces. This regression took place in 1902–1903, a phase often referred to by art historians following Barr as Matisse’s Dark Period. His behavior suggested on its face a character of bourgeois timidity: someone who, having stumbled on a potentially disruptive discovery, failed to follow it up because he lacked the courage of his convictions.

In fact, Matisse turned out to have been caught up without warning in a major political and financial fraud, the Humbert Affair, a scheme carried out by one of the Third Republic’s best-known power couples, Frédéric and Thérèse Humbert. The affair rocked France in 1902–1903, causing a trail of bankruptcies, suicides, and bank failures, even threatening at its height to bring down the government. By the time the scandal broke in May 1902, the villains had fled, leaving as scapegoats their housekeeper and her husband, an unsuspecting couple who had for years provided the Humberts with an innocent front. Their name was Parayre, and Matisse had married their daughter. Their public exposure, followed by the arrest and trial of his father-in-law, left Matisse as the sole breadwinner for an extended family of seven. This is why he switched to painting canvases that were at least potentially saleable.

In order to organize some sort of defense for his father-in-law, Matisse spent much of the next eight months dealing with lawyers as well as prison staff, journalists, the detectives who searched his studio, and the huge vengeful crowds—at times more like lynch mobs—who pursued his wife’s family. To conceal his identity as a penniless painter, widely regarded as a lunatic even by fellow artists, he was forced to abandon his black sheepskin and his workman’s corduroys. The strategy worked, but that first borrowed suit has much to answer for.

The impact of the Humbert affair was devastating for the Matisses and their children. Friends and family closed ranks. The episode imposed an iron reserve together with an indelible suspicion of press intrusion in the painter’s lifetime, and it goes far to explain the famously preemptive discretion practiced ever since by the family archive in Paris.

My first inkling of the crushing weight of humiliation that bore down on Matisse ever afterward came when I started spending time in his native north, where more businesses had been ruined in the wake of the Humbert scandal than in any other part of France. It was a shock to find, on my first visit to his home town of Bohain-en-Vermandois, that nobody had ever heard of him. “Matys? Mathis?” asked the local lawyer, whose firm had once represented Matisse’s father from an office that still stands a few hundred yards from the house where the painter grew up. “How are you spelling that? With an h, or with a y?” Gradually I began to meet an older generation, people in their seventies and eighties whose parents and grandparents had talked about the Matisse boy as a kind of village idiot—le sot Matisse—a dropout with a record of successive failures, who ran away to Paris in the end to be a painter. “Madame, have you seen his paintings?” one old lady asked me in 1991. “A child could paint better than that, Madame.” At the art school in St. Quentin, where the young Matisse enrolled in secret for drawing lessons without telling his father, the elderly college principal was still so bitterly ashamed of his only celebrated ex-student that he could barely bring himself to pronounce the name.

Advertisement

This was French Flanders, a textile region that had been in the grip of convulsive industrialization just over a century before, when Matisse grew up there. He seldom spoke afterward—and then only in terms of darkness and coercion—about the narrow, conformist, and aggressively philistine society that was all he had known for the first twenty-one years of his life. What puzzled me was how someone so starved of cultural contact—someone who had almost certainly never seen an oil painting until he was nineteen or twenty—could have developed such a powerful visual imagination. Where did it come from? What fed it?

The answer lies in the exhibition currently at the Metropolitan Museum, Matisse: The Fabric of Dreams—His Art and His Textiles, which contains an album of silks produced by the weavers of Bohain, famous throughout France in those years for the richness of their color, the boldness of their design, and their insatiable appetite for innovation.2 Their work looked to compatriots like a fireworks display. This is the vision of light and color Matisse said he dreamed of as a boy, and finally managed to recapture as an artist in the great stained-glass windows based on semi-abstract designs of cut-and-painted paper which he produced at the end of his life.

For me the bleakness of the place, and the rancor people still felt at mention of the name “Matisse” half a century after his death, vividly brought home the pressures that had propelled him southward away from his native region toward the Mediterranean sun. But he saw himself to the day he died as a northerner, and it was in the north that I began dimly to understand the brutal metaphors he used to describe his work in unguarded moments. Matisse said the act of painting was for him like kicking down a door, or slitting an abscess with a penknife. In his sixties he told the Hollywood star Edward G. Robinson that he could only ever start a fresh canvas if he felt like throttling someone. Talking to Aragon a few years later, he compared his state of arousal in front of the model to something more like a rape.

Matisse’s most explicit rendering of this violation was Nymph and Satyr, painted in 1908–1909, when the most urgent job facing young painters was to dismantle the vast, imposing, and apparently immovable edifice of Western Renaissance art. (See illustration on page 36.) Matisse’s picture is a harsh, uningratiating, blatantly modern assault on a classical theme. Its flat simplified shapes, thick, coarsely painted contours, and jarring colors—heavy pinks for flesh and sky against a flat, synthetic, acid-green expanse of grass and mountain—make it hard to look at even today. In the opening decade of the century it was too shocking to show to a public that correctly construed Matisse’s painting as a violation of aesthetic as much as moral taboos.

The subject is attempted rape. There is no mistaking the intention of the thickset satyr with abnormally large hands lunging toward the limp naked nymph huddled at his feet with her back turned and her arms flung out in an arabesque of flight or supplication. Art historians have identified her as Matisse’s Russian pupil Olga Meerson, largely on the evidence of her red hair (which struck me initially as odd, since no one has suggested that Meerson had red eyes, like the nymph in the picture, or that Matisse, who was also a redhead, had black hair, like his satyr). Given the personalities involved, and the circumstances under which this picture turned out to have been painted, I find it inconceivable that Meerson actually posed for Nymph and Satyr (which is not to say, of course, that she wasn’t its virtual model). But something complicated is certainly going on here, something that shows what Matisse meant when he said that a painting or drawing, unlike a photograph, enables the artist to draw on emotions and insights over which he has no conscious control. “They synthesize and contain many things the painter himself could not initially have suspected,” he wrote of his portraits.

The same might be said of biography, which aims at a synthesis inaccessible to strictly art-historical analysis. By restoring layers of feeling and imagination to paintings artificially detached from their human and social setting, it seeks to redress the balance of a life trivialized to the point at which spurious assumptions about the artist infiltrate the ways in which we interpret his work. One of the most persistent of these assumptions about Matisse has to do with his treatment of women. Over the past two decades he has mutated in the popular imagination into a more or less standard art-world example of male chauvinist pig. This was one of the first things I was told about Matisse, something apparently so obvious that no evidence has in fact ever been produced to back it up. It was a long time before I could admit that, no matter how long or hard I looked, I couldn’t find any. One of the great surprises of writing Matisse’s biography has been uncovering the lives of the exceptionally powerful women who were his models, chief among them his wife and daughter, together with their successor as his companion and studio manager in the last two decades of his life: the formidable Lydia Delectorskaya.

2.

Art history has felt free to treat the women Matisse painted as objects, and by implication as victims. It was probably inevitable that scholars should take Matisse at his word when he said he felt the same toward his human models as he did to ward a spoon or leaf. Perhaps he did. And perhaps if I had remembered how tenderly—with what delicacy and respect—he talked about the leaves he drew, I might have understood sooner that he was unlikely to treat his other models differently. All the women closest to him were tough and demanding. None of them fits the male chauvinist line that casts them as victims. Each possessed a will as strong as—or, on the painter’s own admission, even stronger than—his own. He could not do without their backing. They gave him the courage and confidence he lacked both as a man and as a painter. He insisted that they criticize his work, which they did, sometimes savagely, and often to devastating effect.

He painted them constantly, but so far as I know the only one who left any comparable record of how he looked to her was Olga Meerson, the supposed prey of the lustful satyr in Matisse’s 1909 canvas. Meerson’s portrait of Henri Matisse (1911) shows a side of him known only to his family and friends. When I first stumbled on this casual, humorous, affectionate little portrait, I felt I was coming close at last to one aspect of the man I was looking for, the invisible man rarely if ever glimpsed by journalists or photographers, the joker I was already beginning to recognize from Matisse’s personal letters. In Meerson’s painting he is sprawled on his own studio couch, wearing the equivalent of denim jeans, the cheap corduroy work clothes favored by French laborers and poor art students a century ago. He looks as comfortable and relaxed as a cat, much as he himself would pose his odalisques many years later in Nice. Matisse, always better at observing other people than being looked at himself, had never posed like this for anyone before, and he never would again (unless you count the drawings made of him on his deathbed nearly half a century later by Alberto Giacometti).

In 1991, when I started working on my biography, there was virtually nothing in the public domain about Olga Meerson beyond her name and nationality, a little clay statuette Matisse produced in 1909, and his portrait of her—made at the same time as hers of him—in the last weeks the pair ever spent alone together in his studio in the Mediterranean fishing village of Collioure in the late summer of 1911.

I spent four or five years searching for her, starting in Moscow where she came from, and where her family (which was Jewish) had been wiped out by the Revolution of 1917. As a young art student, Meerson herself turned out to have been an energetic member of Moscow’s literary and theatrical avant-garde before she moved on, at the age of twenty-one in 1899, to study experimental painting in Munich under Wassily Kandinsky. She became the monitor of Kandinsky’s famous Phalanx Klasse, and a striking figure in the circle of poets and painters surrounding Thomas Mann (Meerson would eventually return to Germany and marry Mann’s brother-in-law).

By the turn of the twentieth century Matisse was already far ahead of his contemporaries, producing work largely unintelligible even in Paris. Meerson left Germany for France in 1905, just in time to catch the Fauve explosion at the Autumn Salon in Paris. (Kandinsky followed her the year after and it seems to have been Meerson, through her fellow painter, Kandinsky’s girlfriend, Gabriele Münter, who introduced Matisse’s work to Kandinsky, himself still a decidedly old-fashioned artist at that point.)

It took another three years before Meerson worked up the nerve to ask Matisse to take her on as his pupil. He refused at first on grounds that she was a greatly gifted painter, and by now so highly trained that she would have to start by unlearning all the skills she had spent the past ten years acquiring. Her portrait of him shows how right he was. It is in a sense an implicit version of the rape explicitly depicted in Matisse’s Nymph and Satyr: the kind of painting—warm, friendly, instantly accessible today—that looked threatening, aggressive, and barbarically uncouth to contemporaries a hundred years ago. “They recoil in horror from the monstrous images of Olga Meerson,” wrote a Parisian critic in 1911. Her portrait of Matisse was a preparatory sketch for a lost canvas which we know only from Guillaume Apollinaire’s description of it as the avant-garde equivalent of an official portrait, dominating the Fauve gallery at the 1911 Autumn Salon so that the whole room became a kind of homage to the leader of the movement.

3.

It was around 1911, too, that Matisse completed the extraordinary double portrait of himself and his wife, The Conversation, which took him four years to paint and which is, if only incidentally, a picture of their marriage. This huge canvas shows Amélie Matisse confronting her husband, who is wearing pajamas, the pair of them positioned stiffly in hieratic poses at either side of an expanse of rich flat blue that glimmers—as the Russian who bought the picture said—like a Byzantine enamel. Even on a human level, the meaning of this stern encounter between husband and wife is more complicated than the straightforward sexual interpretation sugested by Matisse’s striped pajamas.

For one thing, pajama suits before World War I had only recently reached Europe. Initially imported as tea planters’ outfits from India, they were worn in France as exotic leisurewear: a loose, comfortable, pre-1914 version of the modern tracksuit (sleepwear was either nothing or a nightshirt, at any rate in the Matisse household). Matisse adopted pajamas as his basic studio work-clothes, cotton for summer, woolly ones for winter. He painted himself wearing them in the cramped hotel bedrooms or rented rooms with frilly curtains and landlady’s wallpaper that became his improvised studios in Nice for a decade and more after World War I. He went on painting in pajamas until, from the late 1930s onward, he ended up quite literally sleeping with his work, which had by then consumed his life.

In this sense The Conversation of 1908–1912 portrays the profound underlying shape or mechanism of a relationship laid down for both parties on the day, soon after they first met in 1897, when Matisse warned his future wife that, dearly as he loved her, he would always love painting more. A passionate mutual commitment to painting became the foundation stone of their marriage, which only very slowly started to shift after it stopped being a full working partnership. By 1911, that process had barely begun. Matisse told the surgeon René Leriche (who saved his life in an emergency operation long afterward) that he dashed down his first impressions of any given subject in rapid sketches, “like flashes of revelation—the result of an analysis made initially without fully grasping the nature of the subject to be treated: a sort of meditation.” He never forgot the surgeon’s response, which was that he made his own diagnoses in just the same way (“If anyone asks why I say that, I have to admit I’ve no idea—but I’m certain of it, and I stick by it”).

It would be another thirty years after his initial diagnosis in The Conversation before Matisse’s marriage finally collapsed, destroyed by the conflict between life and work depicted in that canvas. The breakup was precipitated by the advent of Lydia Delectorskaya, who had been initially employed by Mme Matisse as her attendant, until Matisse recruited her to model and eventually to manage the studio that absorbed him exclusively by this time (“Madame wanted me to leave,” said Delectorskaya, “not from female jealousy—there was no question of adultery—but because I was running the whole house”).

Matisse and his wife met for what proved to be the last time, ostensibly to discuss details of their legal separation, in July 1939. The meeting took place in Paris at the Gare St. Lazare and lasted thirty minutes, during which Amélie Matisse kept up a flow of small talk while her husband stared at her in silence, frozen in the pose painted three decades earlier in The Conversation. “My wife never looked at me, but I didn’t take my eyes off her…,” Matisse wrote on the night of that final encounter: “I couldn’t get a word out…. I remained as if carved out of wood, swearing never to be caught that way again.”

The drawback to an academic approach that treats the sitters in Matisse’s paintings as impersonally as if they were spoons or leaves is that it imposes an emotional blank at the precise point where the painter’s feelings were most passionately involved. Matisse’s dealings with his models, animate or inanimate, were anything but impersonal. He talked constantly of the need to violate the model, to penetrate and wrest from her (or it) the most intimate secrets. The trouble is that a simplistic, literal-minded interpretation of The Conversation, or any other canvas, too often skews or narrows its meaning. Matisse said as much to his son Pierre, describing relations between his friend Georges Rouault and Rouault’s unhappy family. Rouault’s daughter had just spent two hours pouring out her grievances to Matisse, who did his best to calm her down, and make her see that the internal fires that devoured her father were in fact the source of his greatness as a painter.

Here is Matisse’s description of another beautiful and disturbing picture, The Circus Girl and the Manager, which Rouault had just lent him. Matisse said the entire canvas was a powerful and poignantly expressive portrait of the painter himself, and that there was essentially no difference between his own case and Rouault’s:

A man who makes pictures like the one we were looking at is an unhappy creature, tormented day and night. He relieves himself of his passion in his pictures, but also in spite of himself on the people round him. That is what normal people never understand. They want to enjoy the artists’ products—as one might enjoy cows’ milk—but they can’t put up with the inconvenience, the mud and the flies.

4.

This brings us back to the bruised and vulnerable invisible man, whose existence Aragon said should never be betrayed. Matisse himself here puts the clinching argument for biography. Those who look at his paintings without knowing about—or even noticing—the darkness secreted in their depths do so with a bland enjoyment that tends to expunge or deny the existence of anything more troubling. This is the kind of ultimately disabling vis-ual preconception the painter himself warned against, the frame of mind that has traditionally dismissed Matisse as a lightweight or decorative artist.

That view goes back at least to the 1920s and 1930s, when it became politically correct to write off Matisse as a sleek and prosperous character in a stuffy suit turning out essentially frivolous pictures of sexy girls in transparent tops and harem pants. Half a century after his death it is time to look again at the work Matisse produced in the years between the two world wars in Nice, a period generally supposed to have been one of unbridled sexual indulgence. As the current exhibition Matisse: The Fabric of Dreams—His Art and His Textiles hopes to demonstrate, the painter himself saw it as a time of prolonged and rigorous experiment with colored light and mass, a transitional phase leading eventually to the late great cut-and-painted-paper compositions now generally agreed to be among the most extraordinary inventions of the twentieth century.

By this time Matisse was used to hostility and rejection. The abuse that had pursued him from his first public emergence as a wild beast or Fauve in 1905 would continue right up to his last years, when the paper collages he made in his seventies and eighties were almost universally dismissed, at the time and afterward, as the product of a second childhood. It was my own gradual realization of what this constant pressure must have meant for Matisse that brought me closer in the end to Louis Aragon, whose evasive and unremitting whimsy had once maddened me so much.

The exchanges between Matisse and Aragon took place in wartime Nice in 1942. The two met in Matisse’s studio, where each seized the opportunity to make a portrait of the other. As a member of the banned Communist Party, Aragon had fled south from France’s Nazi-occupied northern zone, and now found himself on the run from the Vichy police. Matisse himself was still convalescent after an emergency colostomy, which his doctors had not expected him to survive. When he did, they told him that he had at most months to live. Aragon wrote a brilliant essay about a “Character called Pain,” centering on the invisible third party always present at their interviews, nipping and snarling silently in the shadows at the back of the studio.

Nothing was ever said about this unseen presence, or about any of the other phantoms that haunted both men. Aragon’s mother lay dying in 1942 (he said that Matisse drew him wearing the expression worn on her deathbed by his mother, whom the painter had never seen). Several close colleagues had already been captured, incarcerated, or shot. Matisse, appalled by what he knew, or suspected, of the fate of Jewish friends, was regularly harrassed in these months by the local police threatening to arrest his companion, Lydia Delectorskaya, who was Russian (like Aragon’s partner, Elsa Triolet).

Matisse, who had been born on a front line, had now seen his humiliated country invaded by German armies three times in his lifetime. Aragon said that neither of them spoke openly about these things, but he recognized Matisse’s response in a linocut illustration for Henri de Montherlant’s Pasiphaë, depicting the heroine with her head and throat flung back as a single white line against a black ground like a shriek of pain. He saw the same directness and urgency in Matisse’s image of Icarus falling through space, an inert clumsy white body with dangling limbs surrounded by bright yellow blobs or sunbursts, destined for the war issue of the magazine Verve. It was made under bombardment and the threat of imminent Allied invasion, when Matisse (who was bedridden, and too frail to be evacuated) said that the flares of yellow in his Fall of Icarus represented the shells exploding in the garden outside his windows.

The Fall of Icarus was a paper cutout, the first essay in a despised childish medium that became so expressive in Matisse’s hands it would eventually supersede oil paint altogether. He said it enabled him to carve straight into pure color, using scissors that were swifter and even more sensitive than brush or pencil. It was in this final phase of his career that he began for the first time to look back to his beginnings, to the oppressive regimes of his youth, and especially to the harsh discipline drummed into him at art school. He said that the academic style of drawing reminded him of one of his small grandchildren sitting in the back of a car and counting the traffic going in the opposite direction: “one car—one car—one car”: a jerky repetitive formula for copying a tree mechanically, leaf by leaf, with none of the rhythmic fluency or coherence of what he called the organic, or Chinese, system, where the drawing itself grows as it spreads across the paper, and the artist learns to pay particular attention to the spaces in between the leaves that shape and define the structure of the tree. Once again, a parallel might usefully be drawn with biography.

The invisible man who emerged from my researches was passionate, generous, and driven. Far from being humorless or heartless, he could be extremely funny, a first-rate mimic and raconteur (Matisse potrayed himself in private all his life in a stream of absurd, scratchy, self-mocking cartoons), as well as a loyal friend, endlessly and unobtrusively kind to those in trouble, especially to fellow painters. Admittedly, he was also almost impossible to live with. The sheer relentless force and intensity of his energy at close quarters made him intolerable at times.

But in the end I came to understand, if I have understood anything, that Matisse sought and found in his work the stability, harmony, and peace he rarely knew in either his professional or his private life. It was the urgency of this need that lay behind everything he did, from the colors flaring on his Fauve canvases to the luminous cut-paper compositions produced half a century later, and their prelude, the last oil paintings he ever made—L’Asie, Red Interior with Blue Table, Black Fern—canvases that looked to Aragon in 1947 “more beautiful than ever, young, fresh, luminous, full of gaiety, more so than ever before, and more confident in light and life.” I hope that my biography may show how that radiance grew from the gulfs of pain and violence inherent in Matisse’s somber reply to Aragon: “I do it in self-defense.”

This Issue

August 11, 2005

-

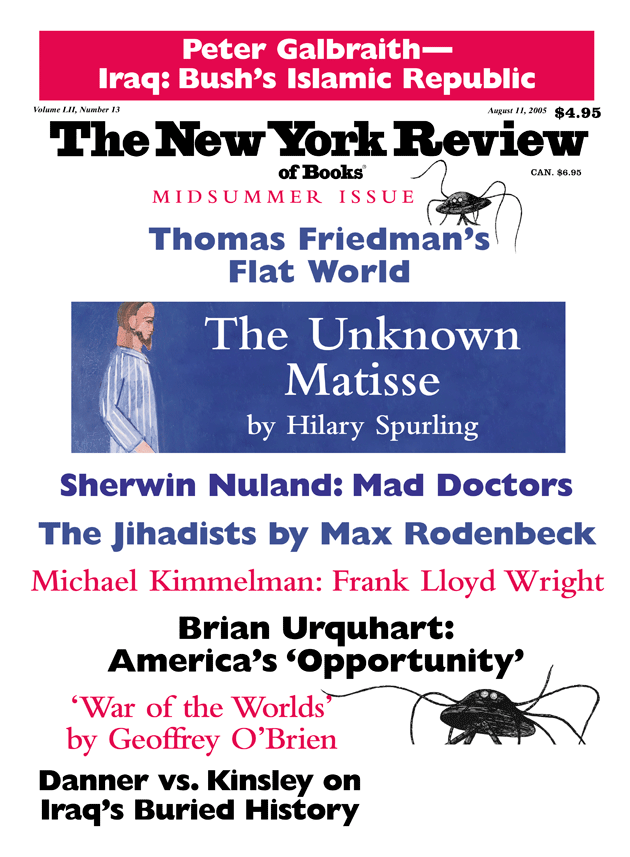

1

In two volumes: The Unknown Matisse: A Life of Henri Matisse, Volume 1: The Early Years, 1869–1908 (Knopf, 1998) and Matisse the Master: A Life of Henri Matisse, Volume 2: The Conquest of Colour, 1909–1954 (to be published by Knopf, September 2005). ↩

-

2

See the exhibition catalog, Matisse, His Art and His Textiles: The Fabric of Dreams (Royal Academy of Arts, London, in association with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2004). The main essay is by the author. ↩