In response to:

Left Out in Turkey from the July 14, 2005 issue

To the Editors:

Christopher de Bellaigue [“Left Out in Turkey,” NYR, July 14] is right: it is not clear whether referring to Armenian genocide still constitutes “anti-national” activity under Turkey’s new penal code. But some prosecutors clearly think it does.

Publisher Ragip Zarakolu is currently on trial for issuing a Turkish edition of George Jerjian’s critically acclaimed The Truth Will Set Us Free: Armenians and Turks Reconciled. The charges include insulting and undermining the Republic and insulting the memory of Atatürk. His trial has been adjourned twice, but is scheduled to resume on September 20, 2005.

During the lulls, Zarakolu—whose publishing house Belge has challenged government censorship for years and who has been jailed and fined repeatedly for his efforts—has been kept busy appearing in court on charges connected to an essay he wrote criticizing Turkey’s policy on Kurdish issues and preparing for another possible indictment for a work he published by a Kurdish author.

It is a familiar story for publishers in Turkey who challenge official taboos: multiple charges, multiple trials, hearings that take place over many months and sometimes years. If they lose, they face prison. If they win, it is only after considerable cost and the kind of harassment that surely serves to make others think twice before publishing similar work.

Hal Fessenden

Chairman, International Freedom to Publish CommitteeAssociation of American Publishers

Larry Siems

Director, Freedom to Write and International ProgramsPEN American Center

To the Editors:

Christopher de Bellaigue’s “Left Out in Turkey” explores important aspects of Turkey’s long history of problems with its minority peoples and Turkey’s current efforts to improve its record, but in his observations on Turkey’s dealings with the Armenian genocide and its aftermath, important facts are left out.

Although Mr. de Bellaigue notes that more than a dozen countries have recognized the Armenian genocide (there are in fact twenty countries that have done so), he fails to note how truculent the Turkish government’s response to this growing movement has been.

In asking the Turkish government to acknowledge its crimes against the Armenians in 1915, the German Bundestag made perhaps the most thoughtful and resonant statement to Turkey yet made by a governmental body. In its resolution of June 15, the Bundestag “deplore[d] the deeds of the Young Turk government in the Ottoman Empire which have resulted in the almost total annihilation of the Armenians in Anatolia.” Refusing to be self-righteous (Germany was Turkey’s World War I ally), the Bundestag acknowledged its own crimes against the Armenian people and concluded with a deeply democratic statement acknowledging “from its own national experience how hard it is for every people to face the dark sides of its past” and asserted “that facing one’s own history fairly and squarely is necessary” and is an essential part of “the European culture of remembrance to which belongs the open discussion of the dark sides of each national history.”

Instead of heeding this advice, the Turkish government is going in the other direction. Turkey has made diplomatic threats and canceled business contracts, pulled its embassy out of France (briefly) after the French recognized the genocide in 2000, and scrapped state meetings with Poland for the same reason this past April. Ankara is now threatening to pass resolutions about genocides they claim these countries have committed. No countries’ records are clean, but they will have to search far back to get the Swedes and the Swiss on this.

Recently, Turkey’s Ministry of Education ordered that the national curriculum must teach students that there was no genocide committed against the Armenians and that all such ideas are groundless. The Turkish Historical Society, a state-controlled organization, published a book, The Armenians: Expulsion and Migration, that was vigorously promoted in Turkey and billed as the final word on the subject. Turkish historian Taner Akçam has called the book “a crime against scholarship” in the recent issue of Journal of Genocide Research, because the authors falsify the history of 1915 by altering the foreign office records of the United States, France, Germany, and other countries whose records testify to a systematic plan of race extermination.

The Ankara Chamber of Commerce spent an estimated $1 million concocting a promotional DVD on Turkey, and paid the European edition of Time to package it with the June 6 issue. The DVD contains an hour-long segment that presents a counterfeit version of the events of 1915, blaming the victims for their fate and absolving Turkey of any responsibility for the eradication of the Armenians of Anatolia. In late June, in Bremen, Germany, Turkish organizations opened an exhibit of photographs and texts that purport Armenians massacred more than a half-million Turks. This absurdity has become a claim of the Turkish government in recent months. The International Association of Genocide Scholars conservatively puts the Armenian death toll at over a million, while many historians put it at 1.5 million. Several years ago, one could find that Ankara would assent to 600,000 Armenian deaths, then it was 400,000, then 300,000, and now it’s down to 200,000. Pretty soon no Armenians will have died.

In the face of rational world opinion, might not this be a moment for the Turkish government to pause and to be a bit self-evaluative? For it is not only Armenians who are asking Turkey to face its past, but the mainstream scholarly and human rights culture, as well as numerous governments. The International Association of Genocide Scholars (the largest body of experts on the subject) recently sent an open letter to Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan that summarizes the unambiguous scholarly record on the Armenian genocide.

Serious democracy is rooted in free intellectual discourse, in educational curricula that are not directed by the government, and in a society’s capacity for rigorous, critical self-evaluation in its public life. The good news is that a small but brave culture of Turkish scholars and writers has emerged in the past decade, like those who were in Istanbul to participate in the May 25 conference on the Armenian genocide that was sadly stopped when Turkish authorities called it treason. These writers are devoted to the serious study of the eradication of the Armenians in 1915, and if they are allowed to express themselves freely they might be able to lead their culture into a new age.

Peter Balakian

Donald M. and Constance H. Rebar Professor of the Humanities

Colgate University

Hamilton, New York

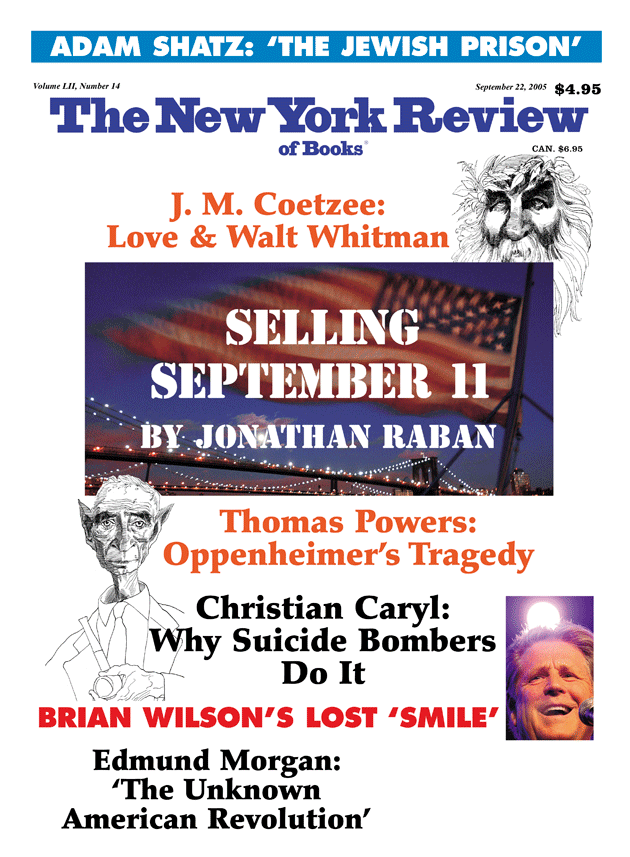

This Issue

September 22, 2005