1.

“The most terrifying verse I know: merrily merrily merrily life is but a dream.”

—Joan Didion, The Last Thing He Wanted

Three times the mother had to repeat herself, telling the daughter her father was dead. The daughter, Quintana Roo, kept forgetting because she was in and out of comas, septic shock, extubation, or neurosurgery, in one or another intensive care unit on the West Coast or the East. Halfway through this black album, The Year of Magical Thinking, the daughter is flown by medical plane from the UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles to the Rusk Institute in New York, but the transfer is complicated. Through a guerrilla action by wildcat truckers who have jackknifed a semitrailer on the interstate, the ambulance must feel its way to an airport that could be in Burbank, Santa Monica, or Van Nuys, nobody seems to know for sure, where a Cessna waits with just enough room for two pilots, two paramedics, the stretcher to which Quintana is strapped, and the bench on which her mother sits, on top of oxygen canisters. And they will have to make a heartland stop:

Later we landed in a cornfield in Kansas to refuel. The pilots struck a deal with the two teenagers who managed the airstrip: during the refueling they would take their pickup to a McDonald’s and bring back hamburgers. While we waited the paramedics suggested that we take turns getting some exercise. When my turn came I stood frozen on the tarmac for a moment, ashamed to be free and outside when Quintana could not be, then walked to where the runway ended and the corn started. There was a little rain and unstable air and I imagined a tornado coming. Quintana and I were Dorothy. We were both free. In fact we were out of here.

If Didion is reminded of Oz, I am reminded of Didion. We’ve met this runway woman more than once before. In Democracy her name was Inez Victor, and after the death of her lover, Jack Lovett, in the shallow end of a hotel swimming pool in Jakarta, she moved to Kuala Lumpur:

A woman who had once thought of living in the White House was flicking termites from her teacup and telling me about landing on a series of atolls in a seven-passenger plane with a man in a body bag.

In The Last Thing He Wanted, her name was Elena McMahon, a journalist who quit reporting on a presidential campaign to wash up on the wet grass of a runway on one of those Carib-bean islands we only pay attention to when they pop up on the Bad Weather Channel, after which she disappeared into the lost clusters and corrupted data of Iran-contra. The narrator/novelist wonders

what made her think a black silk shift bought off a sale rack at Bergdorf Goodman during the New York primary was the appropriate thing to wear on an unscheduled cargo flight at one-thirty in the morning out of Fort Lauderdale– Hollywood International Airport, destination San José Costa Rica but not quite.

There is actually another Cessna in Last Thing, single-engined, “flying low, dropping a roll of toilet paper over a mangrove clearing, the paper streaming and looping as it catches on the treetops, the Cessna gaining altitude as it banks to retrace its flight path.” Inside the cardboard roll, whose ends are closed with masking tape, is a message about November 22, 1963. Inside the novel is a message from the novelist, who has become impatient with “the romance of solitude” and lost interest in such conventions of her craft as the revelation of character:

I realized that I was increasingly interested only in the technical, in how to lay down the AM-2 aluminum matting for the runway, in whether or not parallel taxiways and high-speed turnoffs must be provided, in whether an eight-thousand-foot runway requires sixty thousand square yards of operational apron or only forty thousand. If the AM-2 is laid directly over laterite instead of over plastic membrane seal, how long would we have before base failure results?

The Year of Magical Thinking requires her to be more personal. In one dream, she will be “left alone on the tarmac at Santa Monica Airport watching the planes take off one by one” after her dead husband has boarded without her. In another, a nightmare rescue fantasy, she imagines a rough flight with Quintana between Honolulu and Los Angeles:

The plane would go down. Miraculously, she and I would survive the crash, adrift in the Pacific, clinging to the debris. The dilemma was this: I would need, because I was menstruating and the blood would attract sharks, to abandon her, swim away, leave her alone.

Didion has always juxtaposed the hardware and the soft: hummingbirds and the FBI; nightmares of infant death and the light at dawn for a Pacific bomb test; disposable needles in a Snoopy wastebasket and the cost of a visa to leave Phnom Penh; four-year-olds in burning cars, rattlesnakes in playpens; earthquakes, tidal waves, Patty Hearst. Against the “hydraulic imagery” of the clandestine world, its conduits and pipelines and diversions, she opposes a gravitational imagery of black holes and weightlessness. Against dummy corporations, phantom payrolls, rocket launchers, and fragmentation mines, she opposes wild orchids washed by rain into a milky ditch of waste. Half of her last novel, The Last Thing He Wanted, was depositions, cable traffic, brokered accounts, and classified secrets. The other half was jasmine, jacaranda petals, twilight, vertigo.

Advertisement

In The Year of Magical Thinking, these conjunctions and abutments—scraps of poetry, cramps of memory, medical terms, body parts, bad dreams, readouts, breakdowns—amount to a kind of liturgical singsong, a whistling in the dark against a “vortex” that would otherwise swallow her whole with a hum. This is how she passes the evil hours of an evil year, with spells and amulets. Her seventy-year-old husband, John Gregory Dunne, has dropped dead of a massive heart attack in their living room in New York City, one month short of their fortieth wedding anniversary. She can’t erase his voice from the answering machine, and refuses to get rid of his shoes. Her thirty-eight-year-old daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne Michael, has only been married five months before she is out of one hospital into another, with a flu that somehow “morphed” into pneumonia and was followed by a stroke. One morning in the ICU Didion is startled to see that the monitor above her daughter’s head is dark, “that her brain waves were gone.” Without telling Quintana’s mother, the doctors have turned off her EEG. But “I had grown used to watching her brain waves. It was a way of hearing her talk.”

So we watch her listen—to the obscene susurrus of electrodes, syringes, catheter lines, breathing tubes, ultrasound, white cell counts, anticoagulants, ventricular fibbing, tracheostomies, Thallium scans, fixed pupils, and brain death, not to neglect such euphemisms as “leave the table,” which means to survive surgery, and “subacute rehab facility,” which means a nursing home. But she also consults texts by Shakespeare, Philippe Ariès, William Styron, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Sigmund Freud, W.H. Auden, E.E. Cummings, Melanie Klein, Walter Savage Landor, C.S. Lewis, Matthew Arnold, D.H. Lawrence, Delmore Schwartz, Dylan Thomas, Emily Post, and Euripides. And, simultaneously, she is watching and listening to herself. How does she measure up to the stalwart grieving behaviors of dolphins and geese?

We have no way of knowing that the funeral itself will be anodyne, a kind of narcotic regression in which we are wrapped in the care of others and the gravity and meaning of the occasion. Nor can we know ahead of the fact (and here lies the heart of the difference between grief as we imagine it and grief as it is) the unending absence that follows, the void, the very opposite of meaning, the relentless succession of moments during which we will confront the experience of meaninglessness itself.

Nor did this book have any way of knowing that Quintana would die this August, twenty months after her father. At New York–Presbyterian Hospital, where John Dunne is pronounced dead, a social worker says to a doctor about the brand-new widow: “It’s okay. She’s a pretty cool customer.” Little did they know. What she was really thinking was “I needed to be alone so that he could come back.”

2.

“I realized that my impression of myself had been of someone who could look for, and find, the upside in any situation. I had believed in the logic of popular songs. I had looked for the silver lining. I had walked on through the storm. It occurs to me now that these were not even the songs of my generation.”

—The Year of Magical Thinking

In a 1997 appreciation, practically a CAT scan, of Joan Didion’s novels and essays in these pages, Elizabeth Hardwick spoke of “a carefully designed frieze of the fracture and splinter in her characters’ comprehension of the world,” “a structure for the fadings and erasures of experience,” and, to accommodate “the extreme fluidity of the fictional landscape,” a narrative method of “peculiar restlessness and unease.” She cited bereaved mothers, damaged daughters, “percussive…dialogue,” and “sleepwalking players”; a martyred “facticity” and revelations “of incapacity, doubt, irresolution, and inattention”; “a sort of cocoon of melancholy,” “a sort of computer lyricism,” and “a sort of muscular assurance and confidence”; a “witchery” of “uncompromising imagination” and “an obsessive attraction to the disjunctive and paradoxical in American national policy and to the somnolent, careless decisions made in private life.”

Advertisement

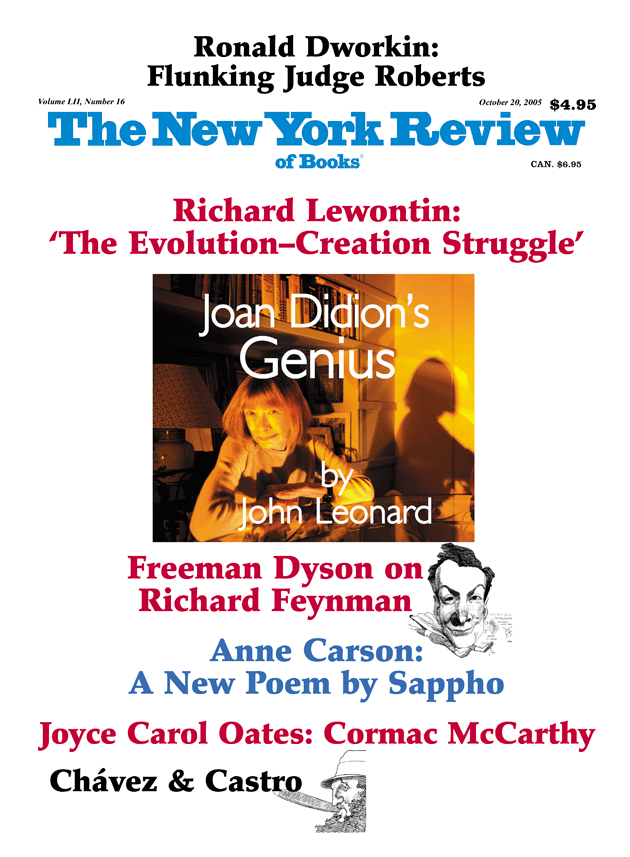

All quite true, but Hardwick missed “the upside in any situation.” Me, too. Didion and I were neophytes in Manhattan during the late-Fifties Ike Snooze, both published by William F. Buckley Jr. in National Review alongside such equally unlikely beginning writers as Garry Wills, Renata Adler, and Arlene Croce, back when Buckley hired the unknown young just because he liked our zippy lip and figured he’d take care of our politics with the charismatic science of his own personality. Later, ruefully, he called us “the apostates.” So I’ve been reading Didion ever since she started doing it for money, have known her well enough to nod at for almost as long, have reviewed most of her books since Play It As It Lays, and cannot pretend to objectivity. Even when I take furious exception to something she says—about Joan Baez, for instance: “So now the girl whose life is a crystal teardrop has her own place, a place where the sun shines and the ambiguities can be set aside a little while longer”; or such condescension as “the kind of jazz people used to have on their record players when everyone who believed in the Family of Man bought Scandinavian stainless-steel flatware and voted for Adlai Stevenson”—I remain a partisan, in part because I’ve been trying for four decades to figure out why her sentences are better than mine or yours…something about cadence. They come at you, if not from ambush, then in gnomic haikus, icepick laser beams, or waves. Even the space on the page around these sentences is more interesting than could be expected, as if to square a sandbox for the Sphinx.

Still, I wouldn’t have thought looking for the upside was a big part of her repertoire. She’s an Episcopalian, not a von Trapp—a declared agnostic about history, narrative, and reasons why, a devout disbeliever in social action, moral imperatives, abstract thought, American exemptions, and the primacy of personal conscience. Inside this agnosticism, in both novels and essays, there is a neurasthenic beating herself up about bad sexual conduct, nameless derelictions, and well-deserved punishments—a human being who drinks bourbon to cure herself of “bad attitudes, unpleasant tempers, wrongthink”; who endures “the usual intimations of erratic cell multiplication, dust and dry wind, sexual dysaesthesia, sloth, flatulence, root canal”; who has discovered “that not all of the promises would be kept, that some things are in fact irrevocable and that it had counted after all, every evasion and every procrastination, every mistake, every word, all of it”; who has misplaced “whatever slight faith she ever had in the social contract, in the meliorative principle, in the whole grand pattern of human endeavor”; who still believes that “the heart of darkness lay not in some error of social organization but in man’s own blood”; who got married instead of seeing a psychiatrist; who puts her head in a paper bag to keep from crying; who has not been the witness she wanted to be; whose nights are troubled by peacocks screaming in the olive trees—an Alcestis back from the tunnel and half in love with death. You know me, or think you do.

Although this Alcestis may have sometimes fudged the difference between fatalism and lassitude, what she does believe in, besides “tropism[s] towards disorder” and the dark troika of dislocation, dread, and dreams, is Original Sin. She tells stories in self-defense: “The princess is caged in the consulate. The man with the candy will lead the children into the sea.” Over and over again in these stories, wounded women make strange choices in hot places with calamitous consequences. This, admit it, is Didion the closet romantic, who actually rooted for the journalist Elena McMahon and the American diplomat Treat Morrison to make it in The Last Thing He Wanted: “I want those two to have been together all their lives.”

But it’s personal—her own intuition and anxiety, frazzled nerves and love gone wrong: nothing to do with the rest of us or the world’s mean work. As she explained in The White Album, “I am not the society in microcosm. I am a thirty-four-year-old woman with long straight hair and an old bikini bathing suit and bad nerves sitting on an island in the middle of the Pacific waiting for a tidal wave that will not come.” To which she added in A Book of Common Prayer: “Fear of the dark can be synthesized in the laboratory. Fear of the dark is an arrangement of fifteen amino acids. Fear of the dark is a protein.”

Thus she’d seem the unlikeliest of writers to turn into a disenchanted legionnaire “on the far frontiers of the Monroe Doctrine,” at the porous borders of the American imperium. Somehow, though, she went left and went south, to discover in the Latin latitudes more than her own unbearable whiteness of being. In El Salvador between “grimgrams,” body dumps, and midnight screenings on videocassettes of Apocalypse Now and Bananas, Didion decided that Gabriel García Márquez was in fact “a social realist.”

In El Salvador one learns that vultures go first for the soft tissue, for the eyes, the exposed genitalia, the open mouth. One learns that an open mouth can be used to make a specific point, can be stuffed with something emblematic; stuffed, say, with a penis, or, if the point has to do with land title, stuffed with some of the dirt in question. One learns that hair deteriorates less rapidly than flesh, and that a skull surrounded by a perfect corona of hair is not an uncommon sight in the body dumps.

So the essayist who in Slouching Towards Bethlehem liked Howard Hughes and John Wayne more than Joan Baez and the flower children, who in The White Album found more fault with Doris Lessing, Hollywood liberals, and feminism than with mall culture and Manson groupies, ends up in Salvador, Miami, and After Henry savagely disdainful of Ronald Reagan and the “dreamwork” of American foreign policy—“a dreamwork devised to obscure any intelligence that might trouble the dreamer.” The daughter of conservative Republicans who has told us that she voted “ardently” for Barry Goldwater in 1964 will describe in Political Fictions the abduction of American democracy by a permanent political class, an oligarchy consisting not only of the best candidates big money can buy, their focus groups, advance teams, donor bases, and consultants, but also the journalists who cover the prefab story, the pundit caste of smogball sermonizers, the spayed creatures of the talkshow ether, and the apparatchiks in it for career advancement, agenda enhancement, a book contract, or a coup d’état. And the writer of fiction who started out with Play It As It Lays, a scary manual on narcissism, leaves town for Panama instead of Hawaii, for Costa Rica and “Boca Grande” and other tropics of “morbidity and paranoia,” where, as if she had graduated overnight from the middle school of Raymond Chandler and Nathanael West to a doctoral program with Graham Greene, Octavio Paz, Nadine Gordimer, and André Malraux, she writes postcolonial NAFTA novels.

It’s not just that the momentum she worries so much about has taken Didion in surprising directions. It’s that we should not perhaps have been surprised. How lazy to have labeled her the poster girl for anomie, wearing a migraine and a bikini to every volcanic eruption of the postwar zeitgeist; a desert lioness of the style pages, part sibylline icon and part Stanford seismograph, alert on the fault lines of the culture to every tremble of tectonic fashion plate. Yes, the Sixties seemed so much to hurt her feelings that her prose at times suggested Valéry’s frémissements d’une feuille effacée—shiverings of an effaced leaf—as if her next trick might be evaporation.

But as early as Slouching Towards Bethlehem, for every syllable on rattlesnakes and mesquite there was also an inquiry into Alcatraz and body bags from Vietnam. The White Album, an almanac of nameless blue-eyed willies, had nonetheless a lot to say about Huey Newton and the Panthers, Bogotá and Hoover Dam, and the storage of nerve gas in an Oregon army arsenal. In After Henry, on a December morning in 1979, she visited the Caritas transit camp for Vietnamese refugees near Kai Tak airport, Kowloon, Hong Kong, where “a woman of indeterminate age was crouched on the pavement near the washing pumps bleeding out a live chicken.” She also just happened to stop in on the Berkeley nuclear reactor, flashing back to her Fifties grammar school days of atom bomb drills and Fifties nightmares of deathly light while she was chatting up the engineer and inspecting the core, the radiation around the fuel rods, and the blue shimmer of the shock wave under twenty feet of water, water “the exact blue of the glass at Chartres.”

Sensitive, to be sure, like a photo plate, a piece of litmus paper, or an inner ear. But writers ought to bruise easily, and obviously the brute world—from California, with its Stealth bombers, lemon groves, biker boys, Taco Bells, poker parlors, cyclotrons, and snipers, where horses catch fire and are shot on the beach, to the rest of the revolting world, with its bird racket, salt mines, banana palms, anaconda skins, casinos, tanks, and Elliott Abrams—has left fingerprints and stigmata. Cynthia Ozick described Isaac Babel as “an irritable membrane, subject to every creaturely vibration.” Although Didion never rode with the Red Cavalry, she has certainly slummed enough with filmmakers, intelligence agents, and social scientists to be very irritable indeed, and, like the anthropologist in A Book of Common Prayer, she has come close to losing faith in her own method and powers of description:

I studied under Kroeber at California and worked with Lévi-Strauss at São Paulo, classified several societies, catalogued their rites and attitudes on occasions of birth, copulation, initiation and death; did extensive and well-regarded studies on the rearing of female children in the Mato Grosso and along certain tributaries of the Rio Xingu, and still I did not know why any one of these female children did or did not do anything at all.

Let me go further.

I did not know why I did or did not do anything at all.

3.

“It’s undeniable, isn’t it, said Kate on the phone to Stephen, the fascination of the dying. It makes me ashamed. We’re learning how to die, said Hilda, I’m not ready to learn, said Aileen; and Lewis, who was coming straight from the other hospital, the hospital where Max was still being kept in ICU, met Tanya getting out of the elevator on the tenth floor, and as they walked together down the shiny corridor past the open doors, averting their eyes from the other patients sunk in their beds, with tubes in their noses, irradiated by the bluish light from the television sets, the thing I can’t bear to think about, Tanya said to Lewis, is someone dying with the TV on.”

—Susan Sontag, “The Way We Live Now”

“Somewhere in the nod we were dropping cargo. Somewhere in the nod we were losing infrastructure, losing redundant systems, losing specific gravity. Weightlessness seemed at the time the safer mode. Weightlessness seemed at the time the mode in which we could beat both the clock and affect itself, but I see now that it was not.”

—Joan Didion, The Last Thing He Wanted

In Harp (1989), his single stab at autobiography, almost a slasher attack on who he was and how he came to be that way, John Gregory Dunne thought out loud about his mother and his brothers and being well-to-do Irish-Americans in Hartford, Connecticut; about Princeton and the Army and murder and suicide; about Henry James, Truman Capote, George Eliot, and Lillian Hellman; about television talk shows, Frankfurt whorehouses, Palestinian refugee camps, cardiac surgery, and why he wrote. He would rather not have thought about why he wrote, but heart trouble had turned him introspective. He seemed to decide that he wrote novels like True Confessions, Dutch Shea, Jr., and The Red White and Blue, and nonfiction like The Studio, Vegas, and Harp, in order to even the psychic score. In general he was full of class hatred. Specifically he was possessed by an Irish-American animus toward WASPs, plus some contempt for his own posturing in this resentment as he recreated the four stages of his “steerage to suburbia” saga: “immigrant, outcast, assimilated, deracinated.”

The army may have helped, too: “If I had not gone into the army as an enlisted man, if I had not experienced what it was like to be a have-not, I doubt I ever would have been so professionally drawn to outsiders.” On the other hand, he wasn’t much for wallowing in the Old Sod, had never been deeply stirred by the Troubles, had no allegiance at all to the IRA, “nor even any particular enthusiasm for Yeats or O’Casey.” Being outside was all right by him, a source of energy, a gift of material, a blackjack, and some body heat. Truman Capote’s mistake, he said, was “to believe himself a citizen of the world of fashion when in fact he only had a green card.”

Stylistically, Dunne was inclined to ridicule. The Irish voice, he informed us,

gets a kick out of frailty and misfortune; its comedy is the comedy of the small mind and the mean spirit. Nothing lifts the heart of the Irish caroler more than the small vice, the tiny lapse, the exposed vanity….

And so he ridiculed himself. This is one of the things a writer does when, suddenly, he is afraid of dying. Dunne said he traveled “easier without the baggage of history, and all of history’s social and genetic freight,” but if that freight is one of the things that kills us, it is also one of the reasons we travel at all.

When, while writing Harp, he found out from the doctors that he was getting a pacemaker instead of a coffin, he told his wife, “I think I know how to end this book now.” He didn’t really. His wife said “Terrific” but he just stopped. After he stopped, I remember thinking that spouses bring another sort of history and a different kind of religion to the breakfast table, and wondering whether it was easier to be Irish if you were married to someone who wasn’t. Still I liked the hostility of Harp. It wasn’t just that after reaching out with Gatsby for the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock, he then swatted it like a mosquito. It was more that, hard as he was on everybody else, he was harder on lyric afflatus, performance blarney, and himself. He seemed to have been born to write his savage novels and nurse his bloody grudges.

When they asked his wife at the hospital whether to fetch a priest, she said yes. Never mind that Dunne, although a Catholic, hadn’t believed in the resurrection of the body. Nor does his Episcopalian wife. What she finds impossible isn’t deciding on priests and autopsies and cremation, on marble plates and Gregorian chants and “a single soaring trumpet” at the funeral, on whether, because she is spending so much time in intensive care with Quintana, to buy several sets of blue cotton scrubs, or when she ought to start working again, but if she should stick a preposition into a sentence of the galleys of the novel John didn’t live to see published: “Any choice I made could carry the potential for abandonment, even betrayal.”

They had been married for forty years. Except for the first five months, when John still worked at Time, they both stayed home and wrote in an amazing intimacy: “We were together twenty-four hours a day.” Even during the occasional week apart, if she were teaching in Berkeley or he had gone to Las Vegas, they talked on the telephone several times a day. When, in the second paragraph of her first column for Life magazine, she dropped a rhetorical grenade—“We are here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for divorce”—upset readers simply weren’t aware that John had edited the column, as he edited everything she wrote, and then drove her to Western Union so she could file it.

You’d think they needed each other to breathe. But you’d also think that Didion, the tarmac woman, has been rehearsing death for many years on many runways. It’s her preferred tropic, as skepticism is her preferred meridian. Maria in Play It As It Lays not only expects to die soon, but also believes that planes crash if she boards them in “bad spirit,” that loveless marriages cause cancer, and that fatal accidents happen to the children of adulterers. Charlotte in A Book of Common Prayer dreams only of “sexual surrender and infant death,” and came to Boca Grande in the first place because it’s “at the very cervix of the world, the place through which a child lost to history must eventually pass.” The body count in Democracy is remarkable, not even including the Reuters correspondent and the AID analyst who are poisoned in Saigon in 1970 by oleander leaves, “a chiffonade of hemotoxins.” In The Last Thing He Wanted, everybody we care about will die, leaving only Arthur Schlesinger Jr. to eat by candlelight and Ted Sorensen to swim with the dolphins.

We might expect if the death is sudden to feel shock. We do not expect this shock to be obliterative, dislocating to both body and mind. We might expect that we will be prostrate, inconsolable, crazy with loss. We do not expect to be literally crazy, cool customers who believe that their husband is about to return and need his shoes.

She picks up the EKG electrodes and the syringes the paramedics left on her living room floor, but the blood is more than she can handle. To the social worker at the hospital, as if he were the emissary of the army at your door in dress greens with bad news from the battlefield, she wants to say, “I’m sorry, but you can’t come in.” She puts John’s cell phone in its charger. She puts his silver money clip in the box where they keep passports and proof of jury service. She calls a friend at the Los Angeles Times so they won’t feel scooped by The New York Times. She will not authorize an organ harvest: “How could he come back if they took away his organs, how could he come back if he had no shoes?” Besides, “His blue eyes. His blue imperfect eyes.”

She is meticulous about ritual, up through and including the service at St. John the Divine, “and it still didn’t bring him back.” She can’t bring herself to throw away a wafer-thin alarm clock he gave her that stopped working the year before he died; she can’t even remove it from the table by her bed. She can’t eat, can’t sleep, can’t think without remembering, can’t remember without hurting, and for six long months can’t even dream. She rereads John’s books, finding them darker. She understands, for the first time, “the power in the image of the rivers, the Styx, the Lethe, the cloaked ferryman with his pole,” the burning raft of grief. No matter where she hides, the vortex finds her.

“Marriage is not only time,” she says; “it is also, paradoxically, the denial of time. For forty years I saw myself through John’s eyes. I did not age.” She tells us that in the rituals of domestic life—setting the table, lighting the candles, building the fire, clean towels, hurricane lamps, “all those soufflés, all that crème caramel, all those daubes and albóndigas and gumbos”—she found an equal, countervailing meaning to her childhood apprehensions of the mushroom cloud. She quotes Eliot from The Waste Land: “These fragments I have shored against my ruins.” And we are encouraged to think that, just maybe, The Year of Magical Thinking is another such stock of rubbled remnants against the worst of nights. But it seems to me as well a habitation of brave hearts and brilliant intellect: a library, an aquarium, a greenhouse, an ice palace, a hall of mirrors, a museum of sacred monsters, a coliseum, and a memory dump. We are surrounded by her fragments. We can shuffle our own magic:

John was talking, then he wasn’t.

You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.

On takeoff he held my hand until the plane began leveling. He always did. Where did that go?

I was thinking as small children think, as if my thoughts or wishes had the power to reverse the narrative, change the outcome.

I had to believe he was dead all along. If I did not believe he was dead all along I would have thought I should have been able to save him.

No eye was on the sparrow.

When someone dies, I was taught growing up in California, you bake a ham.

In the sense that it happens one night and not another, the mechanism of a typical cardiac arrest could be construed as essentially accidental: a sudden spasm ruptures a deposit of plaque in a coronary artery, ischemia follows, and the heart, deprived of oxygen, enters ventricular fibrillation.

After that instant at the dinner table he was never not dead.

Shine, Little Glow Worm.

The votive candles on the sills of the big windows in the living room. The té de limón grass and aloe that grew by the kitchen door. The rats that ate the avocados.

I had allowed other people to think he was dead. I had allowed him to be buried alive.

The craziness is receding but no clarity is taking its place.

We are imperfect mortal beings, aware of that mortality even as we push it away, failed by our very complication, so wired that when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or worse, ourselves. As we were. As we are no longer. As we will one day not be at all.

Let them become the photograph on the table. Let them become the name on the trust accounts. Let go of them in the water.

If Joan Didion went crazy, what are the chances for the rest of us? Not so good, except that we have her example to instruct us and sentences we can almost sing. Look, no one wants to hear about it, your death, mine, or his. What, as they listen, are they supposed to do with their feet, eyes, hands, and tongue, not to mention their panic? If they do want to hear about it—the grief performers, the exhibitionists of bathetic wallow, the prurient ghouls—you don’t want to know them. And maybe craziness is the only appropriate behavior in front of a fact to which we can’t ascribe a meaning. But since William Blake’s Nobodaddy will come after all of us, I can’t think of a book we need more than hers—those of us for whom this life is it, these moments all the more precious because they are numbered, after which a blinking out as the black accident rolls on in particles or waves; those of us who have spent our own time in the metropolitan hospital Death Care precincts, wondering why they make it so hard to follow the blue stripe to the PET scan, especially since we would really prefer never to arrive, to remain undisclosed; those of us who sit there with Didion in our laps at the oncologist’s cheery office, waiting for our fix of docetaxel, irinotecan, and dexamethasone, wanting more Bach and sunsets.

I can’t imagine dying without this book.

This Issue

October 20, 2005