On January 10, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed into law “Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation,” which radically curtail the independence of the country’s nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Russia’s parliament, the Duma, had passed the bill in its third reading in late December by a huge majority: 357 in favor and only 20 against. Recalling an earlier era, Putin’s signing was not made public until word of it appeared a week later in Rossiskaya Gazeta, the government’s official newspaper. The German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who was in Moscow for her first visit, and had publicly expressed her concerns about the bill’s impact on nongovernmental organizations, was unaware that the bill was already a law by the time she met Putin.

With the Duma providing no check on Putin’s power, and after measures to curb businesses, regional governments, and radio and television, the new law is an attack against civil society, one of the last significant parts of Russian public life in which independent critical voices have not yet been suppressed. The arrest and imprisonment in Siberia of the prominent industrialist Mikhail Khodorkovsky has, with few exceptions, silenced business leaders. The Duma elections of fall 2003 produced a pliant legislature in which the liberal opposition was eliminated and the majorities controlled by Putin are able to change the constitution. Instead of being popularly elected, all governors are now appointed by the president (with regional legislative approval). After the state’s shutdown of the last remaining private national television channel in 2003, radio and television now offer few views that challenge the government’s policies. Though they are vulnerable and fragmented, nongovernmental organizations in Russia still express independent opinion as do some newspapers and the Internet. Among the NGOs, the country’s human rights groups have been particularly important in calling attention to the continuing abandonment of the commitment to democracy that the Russians of the Nineties seemed to make after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The new law, which goes into effect in mid-April, has several clear objectives. The first, consistent with Putin’s determination to recentralize power in Moscow, is to broadly expand the authority of an agency within the Ministry of Justice to register, monitor, and audit nongovernmental groups. This powerful bureau, in effect a Russian “homeland security agency,” will have a staff of several thousand, many of them (some predict around one third) drawn from Putin’s natural constituency, the intelligence and security services. Rosregistratsia, as the agency is called, is charged with reregistering all of Russia’s reported 450,000 NGOs. It will seek information on the annual activities of all these groups, including where they get their funding. It will also have the right to attend any NGO-organized event it chooses. It can decide at any moment to request documents and other information that, if deemed unsatisfactory, could lead to an organization’s immediately being shut down. A prominent foundation representative based in Moscow described the new law as “allowing for a line-item veto of [any of] our grants that the agency deems unfavorable.”

The other apparent purpose of the law is to serve as an additional weapon in the Russian government’s battle to forestall on its territory a “color revolution” of the kind that has taken place in other former Soviet countries. The Rose Revolution in Georgia, the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, and, to a far lesser extent, the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan sent shockwaves through the Russian political establishment. Kremlin policymakers responded by mounting a public relations counteroffensive that asserts the primacy of the state and questions the legitimacy of civil society, especially groups that receive funds from abroad. Not only did Putin’s heavy-handed intervention in Ukraine’s presidential election fail to produce the desired outcome, but Putin’s double standard in denouncing Western intervention while championing his own candidate and proclaiming his victory was lost on few. After that failure, Kremlin rhetoric about change not happening in “our backyard” became more vehement.1 Referring shamelessly and inaccurately to Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution as a force in Russia today, Putin asked, “Why do some countries and some people…live by the law and stability [i.e., Russia], while others are doomed to permanent revolution? Why should we introduce this in the post-Soviet space?”

Putin has high approval ratings in the polls, in part a consequence of the benefits from the country’s hydrocarbon revenues. (A $56 billion “Stabilization Fund” has been established with some of the receipts from oil and gas.) No group even faintly resembles a political opposition that could affect his power. The Kremlin, it might seem, could turn its attention to more pressing concerns such as the killing in Chechnya and other parts of the northern Caucasus or the responsibilities that go with Russia’s presidency of the G-8 nations. The conditions that brought about political changes in Ukraine simply do not apply in Russia today, including genuine party competition, the popularity of Victor Yushchenko, a departing president, Leonid Kuchma, without strong support, and eagerness for closer ties with the West, as well as a robust civil society. Nevertheless, Putin and his associates seem obsessively nervous about the Russian parliamentary elections in 2007 and presidential elections in 2008 in which Putin is constitutionally barred from running again. For the Kremlin, the elections have taken on paramount significance. “The Kremlin’s political behavior,” said political analyst Igor Torbakov speaking by telephone, “is guided largely by the preponderance of officials from the world of security. There is a fear of instability created by the 2008 succession crisis and they simply do not want to take chances where they are not in 100 percent control.”

Advertisement

Recently the government has made much of alleged British espionage involving an ersatz piece of rock. On two successive Sundays in late January, state television ran documentaries purporting to show that a rock discovered in a park outside Moscow was packed with intelligence devices that permitted four mid-ranking British embassy officials to communicate with their Russian agents. The FSB, or Federal Security Service (successor to the Soviet-era KGB), announced that it had videotaped the British diplomats downloading information from the apparatus. Two Russians were said to have been detained in the case but, to date, their names, whereabouts, and the charges against them have not been announced.

As the rock story began to unfold, the government attacked another group of alleged conspirators, the members of local NGOs. One of the British embassy officials, a twenty-seven-year-old second political secretary named Marc Doe, was accused of issuing checks to twelve Russian non-governmental organizations including the Eurasia Foundation and the Moscow Helsinki Group, which is concerned with protecting citizens’ rights. Putin said,

The situation is regrettable… when attempts are made to use secret services to work with non-governmental organizations and when financing is carried out through secret services’ channels. No one can then say the money does not smell. Beneficial aims cannot be attained with unsuitable means.

After this announcement, Andrei Kortunov, president of the New Eurasia Foundation, which aims to increase “citizen participation” in public life, commented: “Unfortunately, there is a desire to create a public attitude that every institution that receives foreign money is dubious.” This, he said, “is a signal to all of us. Few distinguish between the FCO [the UK’s Foreign Commonwealth Office] and secret intelligence. To most, they represent one large, monolithic, shady enterprise. Since there’s no free lunch, all those NGOs that received money were collaborating with British spies. By any measure though, the allegations are absurd.” Kortunov explained that the grant his group received from the British embassy for work with the local press was openly awarded after a competition conducted by the FCO’s Global Opportunities Fund.

At a three-and-a-half-hour press conference on January 31, Putin denounced foreign foundations, which he called “puppeteers” (kuklovody) pulling the strings of Russian NGOs. The British spy scandal was invoked to discredit NGOs and to give legitimacy to the government’s case for its new, punitive legislation. The Russian president made it clear that he believes that the central goal of foreign foundations is to fund organizations that will be controlled by their masters abroad. He did not mention that many of the Russian NGOs try to ensure that their own government lives up to its promises, is accountable to its citizens, and guarantees basic rights for all. His view is akin to the claim that the Ukrainian activists on the bitterly cold streets of Kyiv in December 2004 were stooges of US interests (including presumably the babushki, the women in their seventies and eighties who provided soup). As in Soviet times, the Kremlin smugly denies that civic groups might be genuinely concerned with improving the lives of their fellow citizens.

Lyudmila Alexeyeva, the seventy-eight-year-old chair of the Moscow Helsinki Group, one of the organizations accused in the British spy scandal, has been outspoken about the recent turn of events. As the doyenne of the human rights movement in Russia,2 Alexeyeva threatened to sue for defamation the television stations whose documentaries linked the NGOs to espionage. “After this spy scandal, I have a feeling of déjà vu,” she said. “Public opinion is being gradually prepared for the banning of our organization now that the law permits it…. It is part of a large-scale libel campaign against human rights organizations.”

The Moscow Helsinki Group is celebrating its thirtieth anniversary later this year, and Alexeyeva is quick to point out that the organization’s activities will continue in the face of Putin’s threats. “We are not going to refuse the aid of Western funds,” she insisted. At a press conference held by human rights activists on January 31, Alexeyeva observed that the Moscow Helsinki Group had received three grants from a British embassy fund administered in Moscow: for monitoring women’s rights; for support for organizations that plan to visit Russian penitentiaries and prison camps; and for cooperation with Nottingham University on monitoring human rights violations. She added, “From 2004, nobody gave us money at the British embassy, which I sincerely regret.”

Advertisement

Lyudmila Alexeyeva’s uncompromising moral clarity and willingness to speak out against Putin’s repressive policies have helped to rally many to the defense of Russia’s beleaguered NGOs, both within the country and abroad. The European Union, its member states, the Council of Europe, and the US all have had a part in softening some of the provisions of the NGO legislation between the first and final readings in the Duma.

Washington’s readiness to take a position on this matter was unusual for the Bush administration, which has had little to say publicly about the deterioration of democracy in Russia.3 The US has given precedence to getting Russia to cooperate in the “global war on terrorism”; and, in response, Russia has allowed the US to set up military bases in its Central Asian sphere of influence. Bush nevertheless was reported to have raised the issue of the crackdown on NGOs at a meeting with Putin in Pusan, South Korea, on November 18. Though National Security Adviser Stephen Hadley refused to say exactly what was discussed, some of the NGOs said it was helpful to them that Bush put their restrictions on the agenda. In the weeks preceding the meeting, several members of Congress and some administration officials had been publicly critical of the Russian legislation. These criticisms, along with public complaints by Russian NGOs themselves and strongly worded statements from the European Commission, led Putin to call on the Duma to modify the bill. The Duma then stripped the new legislation of three of its requirements: that all foreign organizations reregister as Russian nonprofit entities, that expatriates should be removed from their staffs, and that all informal groups should register with the authorities.

Because they embarrass the state, NGOs concerned with human rights, particularly those that publicize the abuses in the northern Caucasus, face the greatest risk of persecution. In a court at Nizhni Novgorod on February 3, Stanislav Dmitrievsky, the head of the Russian-Chechen Friendship Society, was given a two-year suspended sentence for “inciting racial hatred” against Russians. (His crime was to publish an appeal for peace from Aslan Maskhadov, the Chechen leader killed by the Russians in 2005.) The prosecution had sought a four-year prison term. The case became a cause célèbre for human rights groups, with Amnesty International ready to designate Dmitrievsky a “prisoner of conscience” if he were jailed. When the judge attempted to announce the verdict behind closed doors, the activists present protested, and Sergei Kovalev, the chairman of the Memorial Society and a former human rights commissioner under Yeltsin, denounced the court’s practice as illegal. Kovalev later said, “I would have been happy if the judge [had] decided not to let us into the courtroom. This would have given us an iron-clad reason to demand the annulment of the verdict.” While obtaining a suspended sentence was a small victory for the human rights organizations that worked tirelessly on the case, the outlook for the Russian-Chechen Friendship Society remains bleak. It is simultaneously being audited by both the tax authorities and the Ministry of Justice. Since the new NGO law bars those convicted of “extremist crimes” from heading organizations or sitting on their boards, Dmitrievsky’s position is threatened. He may appeal the case to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg but many judges on that court now come from former Soviet bloc states, and the Strasbourg court is now a far less reliable protector of human rights than it once was.

Under the same article of the criminal code, Yuri Samodurov, director of Moscow’s Sakharov Museum and Public Center, was convicted last year, along with the museum’s curator, Lyudmila Vasilovskaya, of inciting religious and ethnic hatred by exhibiting a show titled “Caution, Religion,” which included artwork that parodied the Russian Orthodox Church. The St. Petersburg lawyer Yuri Schmidt, who represented the defense, said, “Our right to freely express our opinions and convictions is something they want to suppress in order to make Orthodoxy the state religion and turn Russia into a theocracy.” Samodurov was not intimidated. On February 1, he joined Sergei Kovalev (who carried a placard reading “Comrade Chekists—Do You Want a Return to the Old?”) and others in Lubyanka Square to protest the attacks on NGOs.

The Russian authorities have harassed organizations promoting freedom of expression in other ways as well. On January 27, the Russian PEN Center was ordered to pay 1.5 million rubles in back taxes (about $53,000) for the use of land underneath its headquarters. A Russian court promptly froze the organization’s bank accounts, and threatened to seize its equipment and furniture. Though the PEN Center presented the court with evidence that it was a legal tenant, the charges were not dropped. According to Salman Rushdie, then president of PEN American Center, “Russian PEN has been outspoken about new laws targeting nongovernmental organizations in Russia, and now the center is fighting for its life. That is a message that is surely not lost on other organizations and the Russian people as a whole.”

Despite being persecuted, NGOs engaged in watchdog activities continue to be indispensable in denouncing the violent and brutal hazing in Russia’s armed forces. After a cover-up by a general that effectively kept the case hidden for several weeks, the Russian press and television reported the near-fatal hazing on New Year’s Eve of a first-year soldier in Chelyabinsk. Doctors who were forced to amputate the young man’s legs and genitals had reported the case to the local Soldiers’ Mothers chapter, a network that documents abuses in the Russian army. The public fury that resulted when the Mothers group publicized the matter has severely damaged the credibility of Sergei Ivanov, the defense minister and a deputy prime minister, who aspires to become president. Many have called for his dismissal. When the tragedy was first disclosed on January 25, he said, “I think nothing serious happened, otherwise I would have certainly known about it.” Soon after, additional cases of violent hazing in other regions came to light, probably as a result of the exposé of what happened at Chelyabinsk.

The new NGO legislation seems intended to dry up such sources of information. Yet it would be a mistake to underestimate the resilience of organizations such as Soldiers’ Mothers or the human rights groups in Russia. During the Putin years, such groups broadened their membership and were joined by a new generation of younger leaders who are carrying on the work of veteran rights activists from the Soviet era such as Alexeyeva and Kovalev. Among them Yuri Dzhibladze, Igor Kolyapin, Tatiana Lokshina, Grigory Shvedov, and Natalia Taubina have all become important in popularizing concern with rights. Shvedov, who works with Kovalev in Memorial, has spent the last several years in remote Russia stimulating interest in rights among youth by, among other things, circulating public opinion surveys on human rights abuses and publicizing cases that are ignored. Tatiana Lokshina’s Moscow-based NGO, Demos, models its approach on Human Rights Watch not only in monitoring and documenting abuses but also in organizing public campaigns and legal challenges in Russian courts. Yuri Dzhibladze’s Center for the Development of Democracy and Human Rights has tried to get civil leaders to have an effect on human rights policy, and the organization openly demands that Russia fulfill its obligations under UN treaties and Council of Europe conventions on human rights.

Such activists are being challenged by Russia’s use of so-called GONGOs—government-organized nongovernmental organizations. “Russia as a state will support NGOs,” Putin said during his January 31 press conference, a statement that underscored the state’s ambition to bring civil society under its control. In November, the Duma allocated 500 million rubles ($17.4 million) to promote civil society both in Russia and the “near abroad”—specifically, the Baltic States, with their large Russian-speaking populations. These funds are bound to increase the government’s influence, since private domestic financing of NGOs has been meager.

An important source of such private funds has been Khodorkovsky’s Open Russia Foundation, whose accounts were frozen by court order on March 17. The foundation immediately announced, according to a report in The New York Times, that it “was forced to suspend its activities promoting civil society.”4 This action by Putin’s government has delivered a significant blow to the independent human rights movement in Russia. By contrast, the state’s own huge resources and its capacity to force businesses to finance “appropriate” groups give it great power in financing its own organizations. The new 126-member, state-funded Public Chamber—which is supposed to encourage citizens to give their views on legislation and policy—is an attempt to co-opt and undermine the independent NGOs. Its head, Yevgeny Velikhov, has said that his institution intends “to help civil society become organized.” So far it does not appear to have had any effect.

As is often the case, what is happening in Russia is matched by what is going on elsewhere in the former Soviet Union. Kazakhstan’s parliament recently accepted a new draft law for discussion that will enable the government to restrict NGO financing. Uzbekistan, along with Turkmenistan, the most repressive of the Central Asian states, adopted legislation in 2004 that made it extremely difficult for groups to obtain foreign funding legally. It is now considering a draft NGO law that would impose further restrictions. The Uzbek government is also shutting down or taking over most independent nongovernmental organizations.

In Tajikistan, a draft law on public organizations submitted to parliament last November would require NGOs to reregister with the government and it makes people who fail to register criminally liable. In January, the minister of justice of Kyrgyzstan announced that foreign-funded NGOs should be given special scrutiny (though he later backtracked under criticism from Kyrgyz NGOs). Two of the partners in the ruling coalition in Latvia, an EU member state, have introduced a proposal to ban foreign-funded groups from monitoring this fall’s parliamentary elections. Putin’s example—if one was needed—even seems to have extended to China where the government of President Hu Jintao has been engaged in a crackdown for the past several months on the small, mostly unregistered NGOs who receive foreign funding and on journalists displaying too much independence.

How much influence does the Kremlin have in encouraging such attacks on civil society throughout the region? Certainly Russia is setting a standard for moving forward undemocratically, and it has recently done so all the more viciously in its freezing of the Open Russia Foundation’s funds. With Russia as the current G-8 president, US Senator John McCain has gone so far as to recommend canceling July’s annual meeting. “Russia today,” he says, “is neither a democracy nor one of the world’s leading economies, and I seriously question whether the G-8 leaders should attend the St. Petersburg summit.” A former economic adviser to Putin, Andrei Illarionov, has also argued recently that Russia does not qualify for G-8 membership on either political or economic grounds.

Calling off the meeting or kicking Russia out of the G-8 would probably have a harmful effect, since it would widen the differences between Russia and the West. It is in no one’s interest to push Russia further into a neo-isolationism. Russia’s current presidency of the G-8 presents an opportunity for the other members to try to halt the repressive tendencies in Russia. Strong efforts should be made to ensure that NGOs and other civil society groups meet with G-8 leaders in July. At that meeting, much would be gained if member states could discuss the importance of nongovernmental organizations, particularly human rights groups. We can hope that the nations at the meeting will establish human rights criteria for membership in the G-8 and will call for continuing adherence to basic liberal and democratic standards.

More than any other national leader, Angela Merkel has been publicly expressing concern for Russian democracy. In Moscow this January she had one-on-one meetings with human rights activists and other civil society leaders. Her actions should be a model for other leaders. They are in marked contrast with those of her predecessor, Gerhard Schröder, who generally ignored human rights groups during his tenure as chancellor and who has been rewarded since leaving office by being appointed to a lucrative post with Russia’s largest corporation, Gazprom. It is now up to other G-8 members, particularly the United States, which would have the most effect, to hold Russia accountable. If the President and the secretary of state refuse to do so, they will be betraying their own rhetoric about the need to defend democracy.

—March 29, 2006

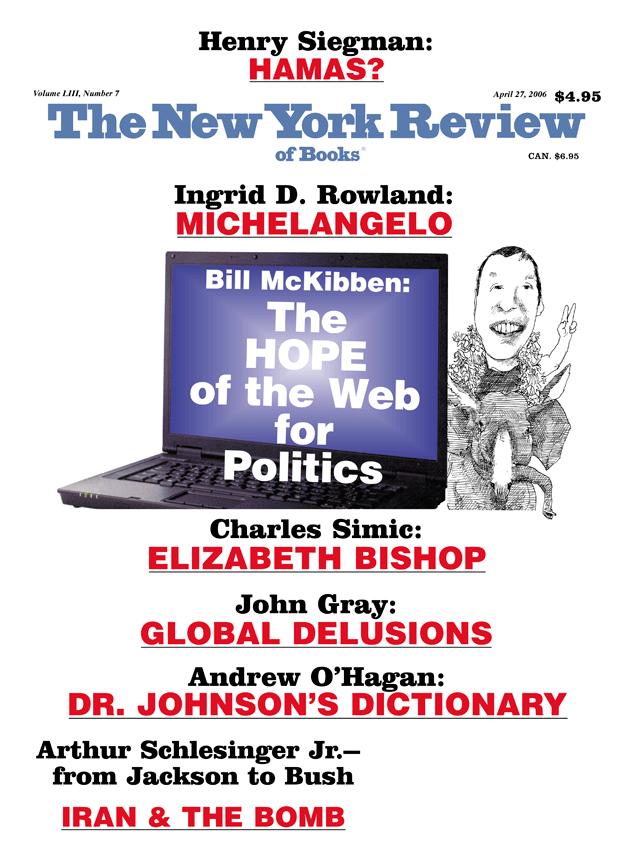

This Issue

April 27, 2006

-

1

Sarah E. Mendelson and Theodore P. Gerber’s June 2005 survey of Russian youth (ages sixteen to twenty-nine) showed that 72 percent definitely did not want an Orange-type Revolution in Russia and only 3 percent were in favor. See “Soviet Nostalgia: An Impediment to Russian Democratization,” The Washington Quarterly, Winter 2005–2006. ↩

-

2

In July 2005, the annual, hour-long meeting of the human rights groups with President Putin coincided with Alexeyeva’s birthday. The Russian leader marked the occasion by presenting her with a bouquet of flowers, making sure that the moment was recorded for broadcast on television nationwide. It was a gesture that acknowledged the symbolic significance of the Helsinki Group and of Alexeyeva’s role as one of its founders in 1976 at a time when the Brezhnev regime was imprisoning many of those who dared to speak out for human rights. ↩

-

3

According to a press report, a debate is underway within the Bush administration about whether to take a harder line. See “Russia Relations Under Scrutiny,” The Washington Post, February 26, 2006. ↩

-

4

C.J. Chivers, “Russia Effectively Closes a Political Opponent’s Rights Group,” The New York Times, March 18, 2006. ↩