In the history of criticism, novelists and poets who write about exhibitions of painting and sculpture have a distinctive place. Their comments on the visual arts may (or may not) be less well informed than the writings of professional art critics and scholars, but some have been capable of subtle, independent observation that makes us see things freshly. The long tradition of literary art criticism began around the middle of the eighteenth century with Diderot’s reviews of the “Salons” and it splendidly continued with critical essays by Baudelaire and Théophile Gautier, Zola and Huysmans, to cite only a few of the most famous names.

The Parisian texts reflect the passionate debates of the Parisian art world, the battles among the Académie des Beaux-Arts, the juries of the Salons, and the “Independents.” After more than two hundred years, Diderot’s pages on Chardin or Hubert Robert remain unsurpassed and the same is true of Baudelaire on Delacroix or Constantin Guys, while in the comments of Proust on Chardin, Valéry on Monet, Gide on Poussin, or Aragon on Matisse we can find original insights into the works of great masters. Horace’s phrase, “Ut pictura poesis“—“as with the painting, so with poetry”—has often been dismissed as an impossibility, yet it remains true that the poetical description of a painting, of its shapes and colors, can aspire to be an echo of the seductive power of the visual arts. The task is a delicate one and it demands from the writer a special openness. Henry James occasionally wrote pieces of art criticism and referred often to art works in his fiction; but he was probably too controlled and fastidious a writer to make his encounters with works of art memorable, and it is hard to disagree with Louis Auchincloss’s judgment in these pages that he was not “in any way a distinguished art critic.”*

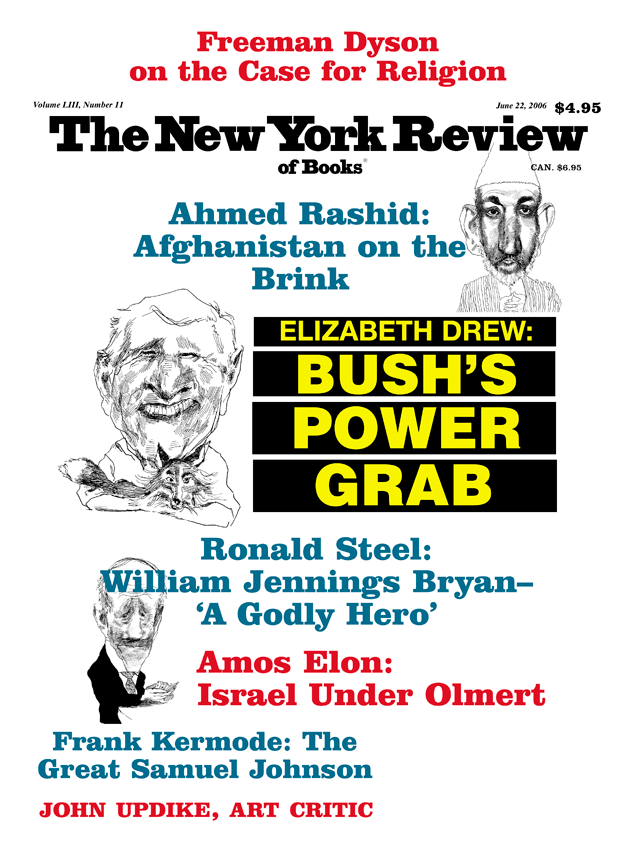

With John Updike the case is different. The relation between his fiction and his essays on art has a refreshing and masterful casualness. He is surprisingly well informed but avoids the inflated jargon of professional art criticism and its theoretical capriciousness. As with his novels and literary criticism his essays on art give pleasure by the quality of his prose, whether one agrees with a specific judgment or not. In his reviews the novelist gives the impression of a writer who strolls through exhibitions, taking his time, admirably relaxed, absorbing and sometimes challenging the catalog. He then writes down his impressions and observations with a fluency and verbal resourcefulness that few art historians could match. Once an aspiring artist himself, he evidently likes these moments of looking and musing in the galleries. Of all his critical prose—and he has written a great deal on modern fiction as well as other subjects—he seems particularly to enjoy his writings on painting and sculpture. He has collected some of his best essays on art in two volumes with the titles Just Looking (1989) and Still Looking: Essays on American Art (2005), the book under review. Still more of his essays on movies, photos, and art are to be found in his copious volume More Matter (1999).

The first essay in Just Looking, a reminiscence of his early visits to the Museum of Modern Art in the Fifties, has some of the qualities of a fairy tale. In “What MoMA Done Tole Me,” he writes, “For me the Museum of Modern Art was a temple where I might refresh my own sense of artistic purpose, though my medium had become words.” The young novelist and critic brings up the traditional question of “ut pictura poesis,” and the hope that there can be stimulating interplay between images and words, between the visual arts and their echo in a poetic language. Looking at the paintings on the walls of museums becomes for him a source of literary inspiration. How, he asks, did artists compose their images of landscapes and figures and charge them with dramatic or symbolic meanings?

For Updike the answers to this question are to be found neither in theory nor in detailed art-historical erudition. Every reader of Updike’s fiction knows that he is a very visual writer, describing with remarkable precision places, rooms, persons, cityscapes, which then have their own part in the stories he tells. With Updike the talents of novelist and essayist become reciprocal in astonishing ways. He is a sensitive perceiver of beauty, the unfashionable word whose use he eloquently justifies in his conclusion to his essay on early visits to MoMA:

These writings are the fruit of just looking, of the pleasures of the eye, which of all our sensory pleasures are the most varied and constant and, for modern man, the most spiritually pliable, the most susceptible to that sublimation called, in pre-modern times, beauty.

Another striking connection between Updike’s novels and his essays on art comes from his being deeply and sometimes mystically rooted in America; his novels—the “Rabbit” series, for instance—have the distinct flavor of regional, even provincial America, and so do many of his essays on art. Updike likes American painting from the days before New York replaced Paris as the center of modern art. He seems deeply fond of that painting’s character, its colors, and its “smell,” even its unsophisticated and occasionally awkward craftsmanship. In his essay on the sublime in American painting we read: “The daily data of American life belong to a raw, evolving present, and not to the circumambient remnants of the past that a European can draw upon when he undertakes a historical landscape in the manner of Poussin or David.” Updike continues: “No, the American Sublime must be taken straight, without even a Hiawatha…to act as guide. America was where Western Man discovered, not for the first time, that what is, is.”

Advertisement

Updike’s visual pleasures are not narrowly restricted to American regionalism. In his first volume of collected essays on art one finds admirable pages on paintings by Vermeer and Antonello da Messina. He is always particularly attracted by quiet paintings in which one senses an intense, reflective attention on the part of the artist to the subject of his work. When he writes on Renoir or Degas—essays one finds in the same volume—he doesn’t seem to be quite at home with them and is even slightly irritated. Among American artists, those who have been deeply affected by the tricks and the elegance of European painting—Whistler or Sargent—are clearly not his favorites. About Sargent he writes:

What, even, did the straw-hatted boatmen and rosy-cheeked midinettes dear to Impressionism mean to him? He came back, with his British accent and the massive embonpoint earned at a thousand dinner parties, to the United States, and to New England, because mural commissions abounded in Boston.

The fashionable glamour and the luxury of Sargent’s canvases arouse a Puritan reserve in Updike and even a moral condemnation. Toward the end of his essay he is full of enthusiasm about Sargent’s uncharacteristic painting of LakeO’Hara from 1916, praising it in words that border on hyperbole: “The unrelieved North American wilderness makes a somber, simple, grandly raw landscape,” and he concludes: “The one thing American about Sargent was the wilderness in his eye.”

Just Looking, Updike’s first collection of essays on art, included very different articles and had a casually eclectic character. The essays in the new volume with the title Still Looking are exclusively on American art. Updike has selected the reprinted articles with more deliberate care so that they form a coherent and well-balanced whole. It is a very personal collection: the homage of a great American writer to the distinctive character—to the specific “local” genius—of American painting. In his introduction he writes: “Editors and their minions are at the mercy of what exhibits happen along, and the coverage is to that extent random. Still, the American vistas surveyed here add up, I would like to think, to a panorama….”

With great charm, but also in a very discreet way, he tells us of his art lessons as a child and how a year spent at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art in Oxford “enlarged my acquaintance with the practice and appraisal of the fine arts.” There was nothing theoretical about his early interest in the visual arts. They were for him practical and seem to have been naively focused on the “mimesis” of nature. The first painting he saw in his childhood on the walls of his mother’s house was an American landscape, a view of Cape CodDune “vast and intimate in its loneliness.” This painting was signed in 1933 by Alice W. Davis, a painter teaching at the University of Iowa, who left no great name—hardly any name at all—in the annals of art history. But it is a sensitive, quiet representation of a corner of American landscape. It is for him a precious trophy of his earliest artistic reminiscence, and he gently calls it an “old friend from my childhood” and tells us how he is still looking at it and learning from it.

These were the modest and intimate beginnings of his visual interests before he started going to museums and galleries. Acquiring his own perspective on the visual arts seems to have been a long, slow, and continuous process. Walking through exhibitions, he is seldom drawn to novelty, experiment, sensation, or a sense of a performed “event.” “The effort of an art critic,” he writes, “must be, in an era beset by a barrage of visual stimulants, mainly one of appreciation, of letting the works sink in as a painting hung on the wall of one’s home sinks in, never quite done with unfolding all that is in it to see.” His patient viewing of paintings, above all paintings from the time of our parents and grandparents and the generations before them, is for him like an escape, a conscious stepping back from the visual flickering that surrounds our daily life.

Advertisement

The dominating subject of the nineteen essays assembled in Still Looking is America; they show a passionate interest in the American landscape, in the faces and bodies of American men and women as they are reflected in art. This enthusiasm recalls at certain moments the rhapsodies of Walt Whitman, though Updike maintains his own tone of sophisticated elegance and of thoughtful distance. For a European reader, such as the writer of this review, Updike’s convinced yet ever so subtle Americanism is the particular attraction of his essays. “Nature His Only Instructor” is the proud title of the essay on John Singleton Copley, America’s first distinguished portrait painter, which contains some of the most thoughtful and reflective pages in the collection. On Copley’s portraits from his early American time we read:

Like an old-time studio photographer, Copley posed his clients in their best clothes and among props suggesting social aspiration; but, like the camera, he could not lie. The tricks of English glamorization were not in his American nature.

The proper American character and the unadorned truthfulness in the blunt presence of Copley’s New England sitters arouse and amuse the aesthetic but also the social interest of the novelist. He pauses before these portraits and waits: “If one attends sufficiently to the surfaces, the interior takes care of itself: this could be the moral of Copley’s American portraits.” In Copley’s later, more elaborate English work these virtues are less evident. Updike feels disappointed by this change and sees it as a loss. Art historians, with their concerns for formal analysis, which usually excludes judgments of taste, might speak here of stylistic development. But Updike is disturbed by the new, fashionable brilliance of Copley’s brushstrokes, and what he calls “the Englishing of John Singleton Copley” is “in some ways a disappointing process.” Still, in front of Copley’s most popular painting, Watson and the Shark, from 1778, he gives one of his subtly observant accounts:

Watson, fourteen years old at the time of the actual incident—bathing in Havana Harbor, he was attacked by a shark, but was rescued—is naked, with the build of a mature man. He and the shark, who share the watery foreground in exactly equal proportions, both have similarly gaping mouths, and appear equally at a loss as to the next step in their relationship. Above them, a small boat has somehow not yet sunk under its load of nine alarmed passengers, who variously reach, stab, and stare. Above them, the harbor of Havana, which Copley took from prints, presents a towered silhouette under a sweeping Gainsboroughesque sky. Watson’s right leg, which was historically bitten off below the knee, discreetly trails off the painting’s lower edge; whether we are witnessing the shark’s assault or Watson’s rescue is unclear.

He then returns to the ambivalent interrelation between Copley’s original Americanism and his adopted “Englishing.” In Watson and the Shark, he writes, “American literalism meets European history-painting in a Gothic, virtually Boschian dream,” and he dwells on the revolutionary effects of this great and moving piece of American art, which became a landmark in the general evolution of history painting: “Romanticism was on the way. Copley’s placement of a black man…set a precedent not only for the black soldier in The Death of Major Peirson“—another of Copley’s history paintings—“but for the Negro figure in Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1817).”

“Epic Homer,” the essay on Winslow Homer, strikes a different note, but here again the American character is the dominating theme. I am not sure if Updike with his refined taste and his preference for the more subtle and idiosyncratic products of art is wholly at ease with the robust qualities of Homer’s work. But he finds telling words and metaphors to praise him. He describes him as a man “who determinedly focused on the plain life and unadorned scenery of the democracy,” and even says: “Homer was painting’s Melville,” a comparison not everyone may be ready to share. He cites Henry James, who had written of Homer:

We frankly confess that we detest his subjects—his barren plank fences, his glaring, bald, blue skies, his big, dreary, vacant lots of meadows, his freckled, straight-haired Yankee urchins….

Updike responds in a way characteristic of his appreciation of “Americanism in art.” “James,” he insists,

was too European…. He could never quell his sensation that there was something intrinsically unworthy in American subject matter. Only the pure, dry American soul, caught in the toils of Old World corruption, pleased him; that soul’s plain and provincial furniture he gratefully eased from his mind.

Updike closes his essay with more cautions and appraising words on the artist’s American character, unspoiled by the refinements of the Old World:

He beautifully exploited his talent and his days; a sense of strain and extravagance attends only the massive exclusion, from his art and, increasingly, from his life, of what might be called European civilization. To a degree no longer possible, he lived as the New World’s new man—self-ruled, resourceful, and beginning always afresh.

The novelist who describes in his fiction the fate and the destiny of American characters has, as an essayist, a special curiosity about the work of queer and unconventional, not always successful, artists. One of Updike’s most sensitive essays deals with Albert Pinkham Ryder, whom Jackson Pollock, before becoming famous himself, had called “the only American painter who interests me.” Ryder’s visionary paintings are nowadays largely ruined, “cracking, shrinking, wrinkling, bubbling, sagging, darkening, alligatoring agglutinations of pigment.” There is something self-destructive about them, which seems to fascinate Updike, who finds in Ryder’s work a specific American kind of heroism and mysticism. “Americans,” he reminds us, “with their basically millennial expectations, admire holy fools, especially in the arts, and the full-blown Ryder, combining Whitman’s beard with Emily Dickinson’s reclusiveness, is our holy fool of painting.” Updike likes such comparisons between painters and writers; whether in words or images, both express for him the same American beliefs and sufferings. The essay on Ryder is significantly called “Better than Nature.”

The title of another essay, “Heade Storms,” is still more laconic. The slumbering yet tense landscapes by Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904) arouse Updike’s admiration, because in their silence, their stillness, they never become showy or melodramatic as is often the case with Albert Bierstadt, the German immigrant, or the muscular Winslow Homer. Updike describes Heade’s painting Approaching Thunder Storm from 1859 in an unforgettable sentence: “Against the utter black, a sunlit man and dog have a cartoonish sharpness of shape and color, as if transposed from a Breughel onto an American beach, whose grasses are highlighted with stabs of the brush handle.” In such phrases, ekphrasis, the description of a painting, becomes a kind of poetry, yet this poetry remains always precise, always connected with Updike’s intense, watchful looking.

Updike has never taken part in the factional battles of the art world, never followed fashions and trends, and he certainly has never paid attention to the art market; he avoids a partisan tone in his judgments, but gives the impression of being perpetually curious. He finds a place for marginal or even disturbing artists. Such a case is that of Marsden Hartley (1877– 1943), the early American modernist, who got in touch with Kandinsky in Germany and lived there in the first year of World War I. Updike describes him as “homosexual, homely, egocentric, shy, slow to develop as an artist, pious in an Emersonian-Episcopalian way.” He looks closely at his painting The Warriors from 1913, in which Hartley intermingles the spiritual dreams of the Blue Rider group with motifs from Prussian militarism. Updike is admirably patient with such an odd combination: “Just as one should not hasten to patronize Hartley’s positive view of a more innocent Germany, one should not rush to read anal symbols into his celebration of military manhood.” He is too serene, too intelligent to spoil his looking by political or moral censorship.

Sometimes Updike the art critic is amused. His brilliant, witty essay on the Polish-American sculptor Elie Nadelman (1882–1946) has the rhythm of a scherzo: “The bronze of a hefty, hunched nude alleged to be Gertrude Stein makes us smile, but her Junoesque mass is something Nadelman will circuitously recover through the coming decades of distinct outlines and smooth surfaces.” Concerning Nadelman’s later career, when the sculptor became more and more successful but also fashionable, we read:

The Nadelmans in their financial heyday collected folk art with an omnivorous zeal, on the theory that the formal basis of all art would emerge from a sufficient accumulation. In the meantime, Nadelman’s shapely sculptures bore an uncomfortable resemblance to the battered dolls that can be found on flea-market tables.

Updike observes and then describes the deterioration of Nadelman’s statuettes, their cheap adaptation to the taste of a fashionable clientele, as he would recount in one of his novels the slow moral dissolution of one of its heroes. But even in this case Updike is far from condemning. The essay on Nadelman ends on a tragic note:

As the stick of his rocket descended, Nadelman’s figures seem to sink back into the all-dissolving waters of being. Perhaps, having early turned against the amorphous ethos of Symbolism—Munch’s swooning women, Moreau’s luminous nebulae—the sculptor yearned to revert to it, an inner world devoid of formal logic.

Updike’s essay on Marsden Hartley begins with an acute historical observation: “These early American modernists have been overshadowed, much as the size of their canvases was dwarfed, by the Abstract Expressionists and the Pop artists, whose spectacular scale and international impact made their American predecessors look indecisive—parochial spirits wistfully caught between imported Cubism and native mysticism.” Updike closes his essay on Arthur Dove (1880–1946) in a similar tone: “Dove is a pioneer of abstract painting but not one of its heroes; his canvases remained sub-heroic in size, and his mainspring remained received sensation rather than vatic promulgation.” But then Updike makes a plea to look afresh at the paintings of this overshadowed pioneer: “Now Dove seems all the more worth cherishing in his edgy, earthbound failure to enter the happy but faraway land where, in the words of Clyfford Still, the most vatic of the Abstract Expressionists, ‘Imagination, no longer fettered by the laws of fear, became as one with Vision.'”

Updike’s essays on American art are a homage to the native character of this art, to its intrinsic, underivative values, to its modest flowering in the days before the New York School became the glamorous center of the international art scene and of an overheated art market. Admitting that many of these old American paintings are not masterpieces, he feels deeply attached to their home-grown truthfulness. His subtle prose tries to protect them against oblivion in the whirlwind of fashionable exhibitions and against the versatile chatter of art criticism. His essays are great examples of sensitive discretion. In one of them, entitled “Early Sunday Morning,” he remarks of the art of Edward Hopper, “He is, to use a phrase generally reserved for writers, a master of suspense.” This telling sentence could as well refer to the most subtle of his own essays on American Art.

In “Walls That Talk Too Much,” his review of the 1994 exhibition “American Impressionism and Realism: The Painting of Modern Life, 1885–1915” at the Metropolitan Museum, he begins by saying, “The Megashow gives way to the talk show—an art exhibit where more time is spent in absorbing the pedagogic text on the walls than in looking at the pictures.” A few lines further he continues mournfully:

…Museums are turning scholarly, delving into their and their fellow institutions’ copious reserves of less than supremely fashionable works of art to assemble purposeful lectures through which we walk as if galleries were paragraphs and paintings were slides of themselves.

It is ironic that a great master of language is reminding curators, art historians, and art critics that the visit to a museum or to an art exhibition should be an occasion for looking, a pleasure for the eye and not an hour of instruction and indoctrination, modeled on the seminar. Updike is deeply convinced that in any writing about art the word should submit to the image, the pen to the eye. In the same review he insists on the distinction between “painting” and “depiction,” a distinction that some art historians, who specialize in what used to be called the social history of art, too easily forget:

Impressionism arose partly in response to the crisis imposed upon the pictorial arts by the arrival of photography; painting was driven to seek out those things that only it could do. The overt art of painting slowly replaced the covert skills of depiction. As one moves through the rooms of this show, giving one’s eyes a rest from the incessant wall-notes with an occasional peek at the paintings, the essential distinction emerges as not that between Impressionism and Realism but that between painting and depiction.

Updike has a Proustian sense of time. On his way through the art of the hectic twentieth century he stops somewhere around 1970. Confronted with a restless visual scenery which unfolds more and more like a gigantic television screen, he has decided to remain old-fashioned and to stay with his early dreams of beauty, quietness, and silence. The last extended essay in Still Looking, about Jackson Pollock, contains a forceful, intense description of the Pollock saga, the dramatic, unhappy, and self-destructive life of a great artist and his tragic early death. Updike turns once again to his favorite, fateful topic: the American character in art. But his tone is now becoming doubtful and broken. Pollock is for him “a heroic American, no doubt, in creating himself from scratch.” For a moment one is reminded of Updike’s essay on Winslow Homer. But then he goes on: “…What this inclusive show”—the Pollock show at MoMA in 1998 and 1999—“makes clear is how close he came to leaving just scratch behind.” Later Updike cites a passage from the late Kirk Varnedoe’s catalog:

Along with Walt Whitman and a few others…Pollock stands in an entirely different class, as someone powerfully understood, at home and abroad and for better and worse in his grandeur and in his misery, to represent the core of what America is.

With gentle irony the novelist plays down the somewhat inflated words of the distinguished curator and reminds us of Pollock’s wavering career between glamorous triumph and alcoholic annihilation: “Is-ness,” he begins, “is all. There is an American tendency to see art as a spiritual feat, a moment of amazing grace. Pollock’s emblematic career tells us, with perverse reassurance, how brief and hazardous the visitations of grace can be.” Two more pages are still to come in Updike’s collection, on Warhol, here called Iconic Andy. It is a somewhat sad and resigned homage to the American genius in art of another time. His last sentence reads: “His”—Warhol’s—“heritage is all around us, whenever reality feels like a television show and art like a silk-screened Weegee.”

This Issue

June 22, 2006

-

*

Louis Auchincloss, “The Eye of the Master,” The New York Review, April 9, 1987. ↩