During the second half of the sixteenth century, one man dominated the making of sculpture in Europe. Known chiefly by his nickname, Giambologna, he was a Flemish artist who worked for the Medici court in Florence. A figure of remarkable creativity and unflagging industry, for nearly fifty years he ceaselessly produced sculpture in every medium, from wax and clay to marble and bronze, and on every scale, from the miniature to the gigantic. Although originally conceived to meet the needs of the Medici and the refined literati of their circle, Giambologna’s sculptures soon had a degree of popularity without precedence in the history of post-classical art. Every king and connoisseur sought work by his hand and his bronzes were exported throughout Italy and the continent. Such was the appetite for his sculpture that his workshop remained open for business long after his death, and some of his models stayed in production for one hundred years or more. Nothing like this had ever happened before.

Giambologna was the first artist since antiquity whose success lay primarily in making sculptures that depicted secular rather than sacred figures and stories. Most celebrated works of earlier Florentine sculpture show heroes from Judeo-Christian history, for example Donatello’s Saint George or Michelangelo’s David. By contrast, Giambologna’s most popular subjects were drawn from classical mythology—Hercules, Venus, Apollo, and the like. This change in subject matter was related to profound changes in basic assumptions about the nature of art. Giambologna and his patrons had new ideas of what works of sculpture could represent, where they should be placed, how they should be viewed, and what they should be used for—in short, they created a new sense of how sculpture and the other visual arts could be part of one’s life.

Despite Giambologna’s importance, modern scholars have often treated him as an artist too rarefied to be of interest for a wide audience. When a major exhibition of his work was held in Europe in 1978, no American museum was willing to show it; and although there are many specialist studies, the standard account of the artist was written in Flemish fifty years ago, and there is only one biography available in English. To remedy the oversight, a pair of related exhibitions have been mounted this year: one show that recently closed at the Bargello in Florence, and another exhibition now on view at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna; an excellent short book in Italian has also just been published.1 The two shows display many of the same works, and the catalogs share some of the same essays. Yet they were organized independently by different curators and they bring to the foreground very different aspects of the artist’s work and career.

Giambologna was born in Douai in Flanders around 1529, and his initial training was in the workshop of Jacques Dubroeucq, the sculptor to Mary of Hungary, Charles V’s sister. Around 1550, when he was about twenty-one years old, Giambologna, like many a northern artist, went on pilgrimage to Rome, where he stayed for two years studying and copying masterpieces of classical sculpture. These works formed one of the standards he aspired to match for the rest of his life. The violent power of the Laocoön, the sophisticated elegance of the Apollo Belvedere, and the formal complexity of the Farnese Bull are elements that can be found again and again in Giambologna’s own sculptures.

After his years in Rome, Giambologna traveled to Florence to study works by Renaissance masters. According to contemporary accounts, he felt “a burning ambition to equal Michelangelo.” One portrait shows Giambologna holding a model by Michelangelo in his hands, and such models could never have been far from his thoughts, for they were a source of continual stimulation and challenge for the younger artist. Giambologna even was to conceive several of his greatest sculptures as ambitious reworkings of Michelangelo’s designs.

Legend has it that the two met only once when the young artist arranged to have an interview with the great man, then nearly eighty years old. Giambologna dared to show him one of his own models, which, hoping to impress the master, he had finished with the highest degree of precision in every detail. In a fit of critical fury, Michelangelo smashed the clay statue and immediately reworked it in a completely different manner, saying, “Now go and first learn how to design a composition before you bother with its finish.” For the remainder of his life Giambologna put his greatest artistic effort into designing and making the models for his sculptures, often leaving much of the execution and finishing to assistants.

Giambologna was an unknown foreigner when he arrived in Florence, but he was soon discovered by Bernardo Vecchietti, a rich merchant and banker. Vecchietti was a financial adviser to the Medici family, and one of the most influential voices on art and culture in the city. Perhaps more than any other Florentine citizen, he was in a position to help a young artist, and help he did. Vecchietti provided the sculptor with room and board for many years, used his influence to help him win some important early commissions, and arranged for him to be placed on the Medici payroll. Vecchietti did still more for the sculptor. Well known as a connoisseur of art and jewels, and an artisan in his own right, Vecchietti was a man of considerable refinement; and the taste, knowledge, and imagination of Vecchietti and his friends were to be fundamental for the direction and development of Giambologna’s art. This may have been especially important since the sculptor seems to have had a limited education beyond his artistic training.

Advertisement

Giambologna’s big break came around 1562 when he won the commission to make a colossal bronze statue of Neptune for a fountain in the central piazza of Bologna. Nearly twelve feet tall, this statue was among the largest sculptures made up to that point in the Renaissance. It shows the Olympian god standing in an energetic pose as he majestically raises and extends his left arm to calm the seas before him; his face beautifully expresses both authority and reserve. By comparison, the contemporaneous marble statue of Neptune by Bartolomeo Ammanati in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence seems inert, flaccid, and dim-witted.

Giambologna soon had a further chance to prove his preeminence. In 1565 he was asked to sculpt for the Medici a large marble group showing an allegory of the Victory of Florence over Pisa. The particular challenge of the commission was that, from the first, the statue was intended to be placed near a large marble sculpture of the Genius of Victory by Michelangelo. In direct competition with the artist universally agreed to have been the greatest sculptor of all time, Giambologna had to tackle a similar theme, and on the same scale. Michelangelo’s statue shows a heroic male youth kneeling on top of a bound and crouching bearded man; the youth appears to rise and turn with a violent corkscrew motion that drives the elder figure further into the ground. For his sculpture, Giambologna replaced the youth of Michelangelo’s statue with a robust Hellenistic goddess, representing Florence, but he otherwise closely imitated the major components of Michelangelo’s design, only reversing the direction in which the figures twist and turn so that the two statues would appear to mirror one another. No other artist in Italy at that time was up to matching the master. From this point until his death in 1608, Giambologna was the most highly regarded sculptor in Florence; indeed, Francesco I de’ Medici called him his favorite artist and said that he might be even better than Michelangelo.

With the blessing of both the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, the Medici had become the dukes of Florence in 1537 and then the grand dukes of all Tuscany in 1569. To affirm and celebrate their rule, they sponsored an ambitious campaign of art and architecture that completely transformed the physical character of the city. They made the Palazzo della Signoria, the former seat of republican government at the center of Florence, into the official ducal residence, and decorated it with statues and pictures championing their reign. In the small neighborhood next to the palace, they demolished every building, including one of the oldest churches in Florence, and erected new administrative headquarters of their government, still known today as the Uffizi (offices). Across the river in the southern half of the city, they acquired the Pitti Palace, made it into another family residence, and constructed the beautiful Boboli gardens behind it. In the surrounding countryside, they built new villas, most notably those at Castello and Pratolino, famous for the wonder of their grounds. And on the streets of Florence and in the centers of other Tuscan cities, including Arezzo, Pisa, and Livorno, they put up statues of themselves.

To make and decorate all the new buildings and gardens, the Medici hired a small army of painters, sculptors, jewelers, tapestry weavers, engineers, masons, and architects, sometimes even importing specialists from abroad. Giambologna was a recognized leader in this army and in 1566 was given both an apartment and a workshop in the ducal palace. As sculptor to the Medici court, he was asked to supply the widest array of statuary. The paintings made for the Medici by Giorgio Vasari and others were often formulaic and uninspired; but Giambologna approached his assignments with extraordinary energy and creativity. Making bronzes and marbles for the gardens of their villas, he virtually invented the fountain statue as a subject for high art. These works range in character from a figure of Ocean as a beautiful Greek god to a humorous statue of an old man of the mountain, Appennino, as a kind of awkward and shaggy giant. Giambologna also made the bronze image of Mercury as a graceful flying youth—one of the most famous of all European sculptures—for a fountain in Ferdinando I’s garden at the Villa Medici in Rome.

Advertisement

Among his other projects, for the grotto at the villa in Castello, he cast life-size bronzes of birds, including turkeys, eagles, and owls, and each he charmingly imagined as an individual character. He put up temporary decorations for state weddings and funerals, including a wax effigy of Cosimo I. He designed glittering silver statues of the Labors of Hercules for the Tribuna, an art treasure room in the Uffizi, and a sleek bronze Apollo for Francesco I’s private chamber. He was even entrusted with the task of erecting two of the most important symbols of Medici rule in all of Florence, the commanding bronze equestrian sculpture of Cosimo I in the Piazza della Signoria and an equally impressive monument of Ferdinando I in the Piazza della Santissima Annunziata. Writing in 1564, Vincenzio Borghini, a humanist art adviser to the Medici, stated that sculpture was “more lordly, richer, and more magnificent” than painting, in part because the costs were beyond the means of a private citizen. The Medici’s desire for princely splendor and awesome magnificence lay behind much of what they sought from Giambologna.

At the same time that he was engaged in creating grand public statuary for the Medici, the artist was also active designing small bronze statuettes for private viewing and interior display. Before Giambologna, statuettes were all but unknown in Florence; maybe as few as two dozen had been made during the previous one hundred years, and these tended to be fairly rudimentary in character, with simple poses and rough and irregular surfaces. Only in northern Italy, especially Venice and Padua, were bronzes a common form of domestic decoration, but often these were utilitarian items such as inkwells and incense burners, not major works of art conceived for a small scale. It is true that the sculptor Antico working for Isabella d’Este and the ruling family of Mantua at the beginning of the sixteenth century had extensively explored a more refined ideal for bronze statuettes, but such experiments in elegance were all but unknown beyond the confines of the Mantuan court.

Giambologna’s statuettes were an immediate popular success. According to one critic writing in the 1580s, there were thousands of bronzes by him in Florentine collections. Surely the writer was exaggerating, but the market for them must have been large and enthusiastic. Starting in the early 1560s, the artist created some ninety or so models for small bronzes; he made numerous casts of the most popular models and had to employ three or four full-time assistants just to help in executing and finishing them all. Giambologna’s statuettes even came to be seen as a distinctive product of Florence; the Medici would commission especially finely wrought versions as diplomatic gifts for other rulers of Europe, including the Holy Roman Emperor and the Elector of Saxony.

One look at Giambologna’s early bronze figure of Venus After Her Bathis enough to see the reasons for his acclaim (see illustration on page 47). A small statuette that fits comfortably in the palm of the hand, it shows a young voluptuous woman kneeling on her right leg, as she raises her left arm and dries her left breast with a cloth held in her right hand. The sculpture is immediate and sensuous and yet remote and ideal, as if something remembered from a dream. Unmistakably, the appeal of the bronze is partly erotic. The viewer is meant to examine, and to imagine caressing, the firm buttocks, the ripe hips, the supple back, and the soft, full breasts of the figure. At the same time, however, some proportions and shapes of her body have geometric qualities that make her appear almost alien: her neck is unnaturally long and columnar and her nose is almost a pure rectangle. Similarly, the look on her face—inward, still, and passionless—seems from another world. She is a goddess, and for all her loveliness, she remains immaculate and inaccessible.

The bronzes of male figures have a very different character—they depict gods or heroes in vigorous action rather than in dreamy repose—and yet they too were made to be examined with a kind of rapt concentration normally reserved only for things we love. Almost invariably they show the entire body tense with movement and near the climax of action. In Hercules with a Club, for instance, one sees the hero at the very midpoint in the swing of his weapon; preparing to strike, he has raised his right arm high over his head and he is about to bring it down with supreme violence. One can feel the surge of power that will be released: a sense of urgency and excitement courses around the entire figure. This impression is intensified by both the outline of the body—all the limbs are extended, creating a pinwheel of motion—and the surface of the bronze, rippling and scintillating with life.

Giambologna’s bronzes are masterpieces of virtuosity. Every muscle, ligament, vein, and curl is rendered with astonishing immediacy and convincing veracity. The vividness of the details is so dazzling that the viewer cannot help but marvel at their artistry: they compel admiration for the remarkable skill and exhaustive care with which Giambologna and his assistants have wrought them. Artfulness is on display as well in the composition of the poses. The female bronzes are made up of curves that interconnect with heavenly grace; likewise the bronzes of the male figures seem planned more to show off bold movements, naturalistic anatomy, and finely crafted details than to illustrate a story or depict a figure’s psychological state or moral character.

We can be sure that Giambologna thought of his work primarily in aesthetic terms. In 1579 he made for Duke Ottavio Farnese a large bronze statuette of a young man holding aloft a beautiful nude woman. Discussing the piece in a famous letter to the duke, Giambologna stated, “Regarding the two figures, they can be interpreted as the Abduction of Helen, or perhaps that of Proserpina, or that of the Sabines: I chose them [only] to give expression to my knowledge and study of art.” More remarkable still, immediately afterward he began a colossal marble group in which he added a third figure to the composition of the statuette. The sculpture was judged to be so beautiful that Francesco I had it erected in the Loggia dei Lanzi next to the ducal palace on the Piazza della Signoria, and a competition was held to come up with a myth or legend that the statue might represent. The Rape of Andromeda was initially suggested but the Rape of the Sabines finally was deemed to fit the sculpture best and Giambologna made a bronze narrative relief for the pedestal to help identify it as such. As has been rightly noted before, this was the first occasion that a monumental work of art was erected in a public setting solely for its beauty and visual appeal. What makes this especially notable is that up to that point, all the sculptures on the square, including Donatello’s Judith and Michelangelo’s David, were works of great symbolic significance, representing the strength and the good government of Florence and God’s protection of the city.

Throughout the Middle Ages and early Renaissance, the justification for art was said to be its usefulness for moral instruction. Religious images were conceived as an aid in the remembrance of the saints or as the Bible of the poor; and secular images were defended as illustrations of exemplary heroes and deeds that instilled the desire for virtue in the viewer. Borrowing language from Cicero, Horace, and Quintilian, humanists in the early Renaissance agreed that the visual arts, just like rhetoric and poetry, should delight, move, and instruct. In the time of Giambologna critics still believed in the moral value of the visual arts, especially of religious images; but they put new emphasis on the primacy of delight. For example, in 1564 Vincenzio Borghini wrote an essay on painting and sculpture in which he stated that “pleasure is the essence of art, utility is an accident.”

When Giambologna and his friends spoke of the pleasure of art, surely they had in mind the sensual gratification that came from looking at beautiful things. But they also thought of such pleasure as the satisfaction and the fulfillment that arises from the use of one’s faculties as a human being. We can be relatively certain of this because of the book Il Riposo, written by Raffaello Borghini in 1584. Raffaello was Vincenzio’s grandnephew and an important humanist; and it was Raffaello who gave Giambologna’s colossal marble of the Rape of the Sabines its name. Il Riposo is a dialogue in which Giambologna’s patron, Bernardo Vecchietti, and three other men discuss their opinions of the visual arts. Vecchietti is the leading figure in the text: indeed, the title of the book is taken from the name of his villa, which lay in the hills outside of Florence.

Near the beginning of the book Borghini gives a long description of the place. He recounts the physical beauty of the grounds, the abundance of its orchards, the purity of its waters. He praises the delicacy of the cuisine and the excellence of the wines. He marvels at the wealth of the collections: porcelain, silver, crystal, prints, paintings, drawings—including sheets by Michelangelo and Leonardo—and most of all “the many figures in wax, clay and bronze” by Giambologna. “In short,” he concludes, “at the villa you can find everything you need to give pleasure to the body and nourishment to the mind.”

In the early Renaissance, art collecting had been a restricted activity, chiefly confined to princes of church and state, and done in no small part as an expression of political power. It was virtually an obligation of office, and for the Medici and other rulers in the later Renaissance, it remained so. Yet in the sixteenth century collecting became a far more common passion, pursued by all manner of rich private citizens, for whom it may have been an emblem of nobility, but not of state power. Freed from political function, collecting could serve other ends of a more personal scope. For Bernardo Vecchietti and the other men in the circle of Giambologna, art was one of the worldly goods whose possession and enjoyment help a cultivated person to achieve a measure of happiness on earth. Perhaps for the first time in European history, art was seen as a component of the ideal life.

During the sixteenth century the fundamental text on the relation of pleasure and happiness was Book X of Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics. Aristotle states,

One is led to believe that all men have a desire for pleasure, because all strive to live. Life is an activity, and each man actively exercises his favorite faculties upon the objects he loves most. A man who is musical, for example, exercises his hearing upon tunes, an intellectual his thinking upon the subjects of his study, and so forth. But pleasure completes the activities, and consequently life, which they desire…. Those pleasures, therefore, which complete the activities of a perfect or complete and supremely happy man…can be called in the true sense the pleasures proper to man.2

That Giambologna’s sculpture was a landmark in the secularization of art has been said often before, and so it was. But the new attitude that he and his patrons espoused should not be seen merely as an early instance of the ideal of art for art’s sake. Rather, they saw his sculpture as an exalted experience that would engage the mind and stimulate the senses and thereby help viewers to understand better their own humanity.

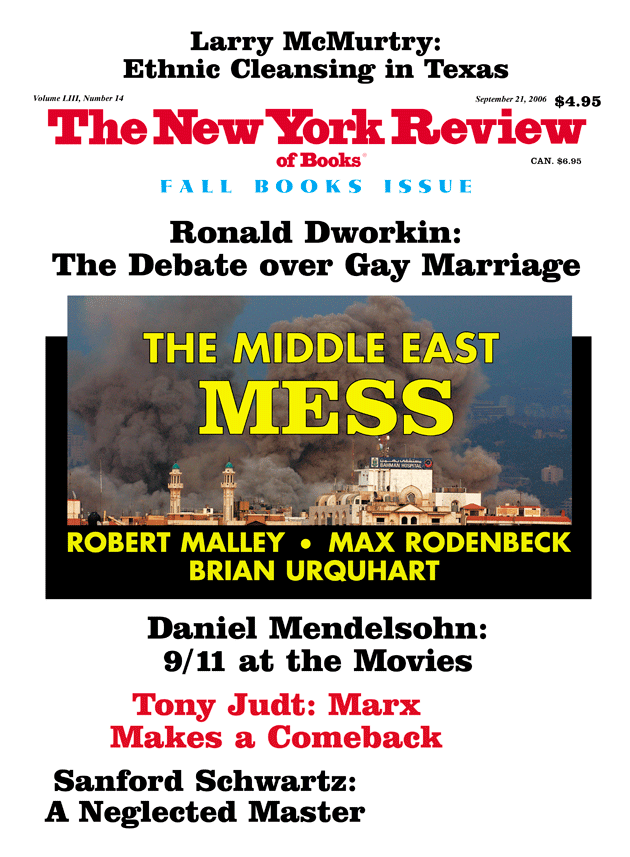

This Issue

September 21, 2006

-

1

Davide Gasparotto, Giambologna (Rome: L’Espresso, 2005). ↩

-

2

Aristotle, Nichomachean Ethics, translated by Martin Ostwald (Bobbs-Merrill, 1962), pp. 281–286. According to Charles B. Schmitt, Aristotle and the Renaissance (Harvard University Press, 1983), p. 38, at least twenty-five editions of the Ethics were published between 1538 and 1600. ↩