Strange exodus, with no Promised Land and no Moses. But in May 1940 in France, Belgium, and Holland, the word “exodus” came into use at once. It must have seemed appropriate to the biblical proportions of this human tide, which Hanna Diamond calls the largest population movement in history up to that point. On May 10, the very day Hitler launched his attack on France and the Low Countries, people began leaving their homes in potential combat zones. At its peak, between late May and mid-June 1940, some eight million French, Dutch, Belgian, and other refugees—no firm count could ever be made—were on the road. Counting witnesses, helpers, and relatives, a majority of the French population was affected by the exodus.

The monumental jam of weary pedestrians, laden peasant carts, jalopies with a mattress on the roof, luxury limousines, and retreating military that clogged the highways of western France from mid-May into mid-June 1940 was the single most powerful image of the fall of France. Observing from the air, French air force pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry thought of a grape squeezer: a whole people was flowing along the roads “like a black juice.”1 Soon a large part of this people would accept the father figure of Marshal Philippe Pétain with relief.

In her readable and well-informed book, the first general account in English and one of the most satisfactory in any language,2 Hanna Diamond states that the exodus of 1940 had no precedent. That is true if one refers to its extent and its political impact. But noncombatants had always fled from battlefields. Pitiful refugees with their meager possessions trying to escape from armies were a familiar form of misery from earliest times up through the particularly devastating Thirty Years’ War that began in 1618 and on to the evacuation of Moscow as Napoleon approached in 1812.

By the outbreak of World War I, warfare had come to encompass far wider areas and to entail far greater destruction. The exodus of August and September 1914—contemporary journalists already used the term—in which civilians fled the invading Germans in Belgium and northern France reached proportions approaching those of 1940. About a million Belgians escaped into neutral Holland, where about 100,000 remained interned for the duration of the war. Another quarter of a million Belgian refugees reached England. Still others entered northern France, where the local inhabitants joined them on the road.

Rumors of atrocities by German soldiers fed the urge to flee. After World War I, such rumors were often debunked and the stories of German soldiers’ misdeeds attributed to Allied war propaganda. Recently this subject was brilliantly demystified by John Horne and Alan Kramer of Trinity College, Dublin, who showed that while the babies with severed hands and the mass rapes were mostly if not entirely imaginary, and while the Allies did indeed use these rumors for propaganda, German soldiers’ violence against civilians in Belgium and northern France was very real.3 Drawing upon its belief that armed civilians (francs-tireurs) had harassed German troops from the rear in France in 1870, the German high command had prepared its soldiers to expect civilian resistance and to deal with it severely. They could do so in good conscience, they were told, for such resistance was contrary to the laws of war. In the shock and disorientation of battle, some German soldiers, believing that civilians were firing upon them from attics and steeples, burned villages and killed their inhabitants, at times in a fury akin to panic.

During August and September 1914, some six thousand Belgian and French civilians were murdered in this way in 129 major incidents (defined as involving more than ten dead) and many minor ones. German Protestant soldiers often singled out Catholic priests as alleged ringleaders. Women and children were not spared, for soldiers believed that they mutilated wounded or dead Germans. Right up to 1945 the German high command and government persisted in accusing the Belgian government of ordering civilian resistance in 1914, and defended the soldiers’ actions as legitimate self-defense against francs-tireurs. Horne and Kramer find no evidence to support this interpretation.4 In some cases the stray gunfire that precipitated such incidents seems to have come from other German soldiers, sometimes inebriated. We know today, of course, that any nation’s soldiers, Americans included, are capable of committing such panic reprisals against a demonized enemy.

All this is worth recalling in some detail because the flight of 1940 was directly related to folk memories of what had happened twenty-six years earlier, as Diamond points out. Horne and Kramer report that the villagers of Orchies, in the French department of the Nord, where houses had been burned and inhabitants killed in 1914, left their reconstructed homes, still far from the battle zone, the day the invasion began on May 10. As Simone de Beauvoir recounts in her memoirs, the macabre stories about babies with severed hands resurfaced among the refugees. Better-substantiated memories from World War I that encouraged flight in 1940 were the near starvation in the occupied zones in Belgium and northern France in 1914–1918 and the deportation of young men to work for the German war effort.5 According to Diamond, many of the 1940 refugees attributed their decision to flee to a fear of being forced to work in German labor battalions. Jews, of course, had their own good reasons for not wanting to fall under Nazi occupation.

Advertisement

What was unprecedented about the exodus in May and June 1940 was its duration and its political aftereffects. Whereas in September 1914 the front stabilized and the refugee flood stopped, in June 1940 the German armies continued to advance right up to the moment the Franco-German armistice was signed on June 22. Refugees had to go much farther and stay on the road longer. Some of the worst tie-ups and fatalities occurred at the Loire River crossings in mid-June, far south of any area affected by the exodus of 1914.

The second major difference was the political effect. The exodus of August and September 1914 was blamed on the Germans. The French blamed the exodus of May and June 1940 on their own Third Republic. The refugees complained almost unanimously of having been abandoned by the public authorities. Indeed it was often the local mayor who set off the departure. Most prefects left, some of them arguing afterward that it was wrong for a representative of the French state to let himself be taken hostage by an enemy army. In some localities firemen drove off on their engines, and policemen joined their fellow citizens on the road. Even with an intact administration the exodus would have produced disorder. The absence of many local officials certainly made things worse. The nearly universal sense that the Republic had failed to manage the crisis was a major reason why so many French people wanted another kind of government in June 1940, and why they voted twenty-five to one in a referendum after the liberation, on October 21, 1945, to replace the reviled Third Republic with a new one.

A third major difference in 1940 was that cities were now targeted more frighteningly than in any previous war. On August 6, 1914, a German dirigible had dropped a few bombs on Liège, Belgium, the first aerial bombardment of a city. By the time World War II began Europeans had learned what to expect from Guernica, the Spanish-Basque town bombed by the German Condor Legion on market day, April 26, 1937, followed by the strafing of the fleeing citizens. Even Germans had to be reassured (falsely, as it turned out) that Hitler would never let the Reich’s cities be bombed.6 Urban Europeans’ fears were not misplaced. Warsaw and then Rotterdam became the first major cities to suffer carpet bombing. After the center of Rotterdam was razed on May 14, 1940, killing more than eight hundred people, residents of other cities prepared to leave. Whereas war refugees had traditionally fled the rural zones where armies fought, in May and June 1940 great cities emptied out. The evacuation of Paris, ordered on June 10 for government officials and essential workers and spontaneous for millions of others, rightly forms a centerpiece of Diamond’s book.

No single story encapsulates the experience of the exodus. Some of the fleeing citizens returned home in a few days, while others remained displaced for the rest of the war. Some could stay with friends or family or had even foresightedly rented something just in case; others moved blindly south with no destination, sleeping in their cars or on the roadside. Some families lost their possessions and even the lives of relatives or children, as enemy aircraft strafed the columns (why they did this does not seem to have been explored by any scholar). Many adolescents, by contrast, remembered the exodus as a holiday lark, a kind of impromptu camping trip in which one could discard conventions as during Carnival. There were scenes of cowardice and crime, as refugees stole each other’s food and possessions. These were matched by scenes of generosity, as proprietors of large houses and barns offered shelter, and churches and villages organized relief. The stresses of the exodus revealed every human characteristic in magnified form.

Such heightened experience calls for a novelist. The recently published Suite française by Irène Némirovsky, written in 1942 shortly before the author’s arrest by French police and deportation to her death in Auschwitz, is perhaps the most evocative fictional account of the exodus.7 Hanna Diamond did the best she could to tell refugees’ stories in the first person by using such traditional historians’ sources as diaries and letters and interviews, along with some of the sparse official record. But diarists and letter-writers always hide something. It took the sardonic eye of Irène Némirovsky to imagine well-off Parisians wrestling with the problem of what valuables to try to save—a matter diarists seem not to have wanted to mention.

Advertisement

Each social stratum faced this problem in its own way. The farmers took along their tools and animals, and their overloaded carts were abundantly photographed. The wealthy could be more discreet about the contents of their automobiles. One of Némirovsky’s characters successfully saves his precious collection of porcelain on the round trip, only to die senselessly back in Paris, hit by a car on a street corner. Némirovsky also imagined disturbing scenes of moral disarray, as in the horrifying moment when a group of boys from an orphans’ home drown the priest who has accompanied them south. Hanna Diamond came up with nothing quite so unnerving, but she shows how powerful was the impression that civilized order had collapsed.

Some of Diamond’s best pages explore the various images of the exodus and their uses. Marshal Pétain’s new regime at Vichy skillfully exploited the impression of abandonment and moral decline to build legitimacy for its replacement of the “decadent” Third Republic by a new authoritarian state and moral order based on “family, work, and homeland.” In some cases, however, this great uprooting led not to an acceptance of the father figure Pétain but to a readiness to resist both him and the Nazis. A fair number of resistance narratives begin with the exodus as the first step out of routine conformity. Nazi propaganda images of German soldiers helping the refugees enjoyed some success, aided by Hitler’s order to treat civilians well this time. The campaign of 1940 involved few atrocities like those of 1914, though they reappeared, as in the massacres of Ascq and Oradour-sur-Glane in June 1944, when the francs-tireurs of the French Resistance made German soldiers feel insecure once again.

The exodus of 1940 still poses unanswered questions. How it started is one. Was it spontaneous, or ordered by French authorities? Or did the Germans set it off in order to exacerbate the chaos and to clear the country ahead of their units? Clearly all of the above are right answers at various places and times: the government evacuated frontier zones according to prearranged plans, while further departures were spontaneous. German policy on this matter does not appear to have been studied in the German army’s own records. Once begun, the exodus grew of its own momentum. Columns of refugees tended to dislodge the residents of each new village as they arrived.

Another unresolved question is whether the exodus contributed to French defeat, by making it harder for the commander in chief, General Maxime Weygand, to organize his last-ditch defense on the Somme River in early June. That it made military movements harder seems beyond doubt. Diamond has not made the military campaign clear in her account, but she accepts the judgment of prominent French historians that the battle of France was already lost before the exodus reached its peak,8 and that it was lost by the generals rather than by the behavior of citizens. Churchill, however, Diamond notes, took steps to prevent something similar from happening in case a German force invaded Britain.

Whether or not the exodus of May and June 1940 had precedents, it has had many sequels. Even before World War II had ended, the Germans of Central Europe fled before the advancing Soviet armies. The eastern Germans’ flight from battle was soon prolonged in the forced emigration of entire German populations from their former homes in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Romania. In all, some twelve million Germans either left or were expelled, swelling the mass of Jewish and other “displaced persons.”9 The flight from battle had merged into ethnic cleansing. During the post-1945 period there have been a great many population flights from wars and civil wars, some of which had the explicit intention of removing unwanted populations. The sight of formerly comfortable people taking to the roads, so abundantly photographed in 1940, has become a cliché. Nevertheless it is still a powerful image. The sight of New Yorkers streaming blank-faced up lower Broadway on September 11, with no particular destination except away from destruction, may have touched deep memories in France, where the sympathetic response was strikingly spontaneous and broad. It is unlikely that we have seen the last of exoduses.

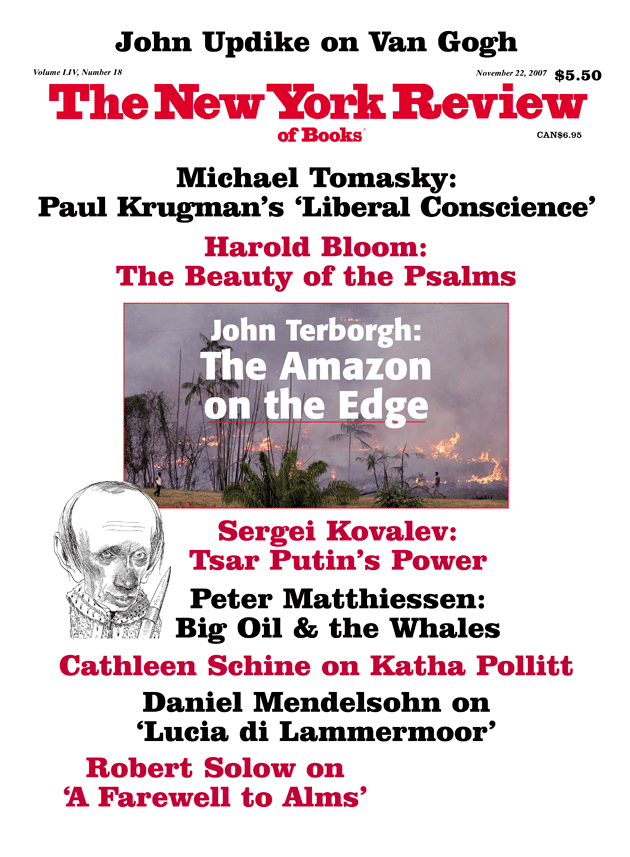

This Issue

November 22, 2007

-

1

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Pilote de guerre (Paris: Gallimard, 1942), p. 95. ↩

-

2

Later works in French, mostly anecdotal, have not supplanted Jean Vidalenc’s classic L’Exode de mai–juin 1940 (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1957). Hanna Diamond is also the author of Women and the Second World War in France, 1939–1948: Choices and Constraints (Longman, 1999). ↩

-

3

John Horne and Alan Kramer, German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial (Yale University Press, 2001). ↩

-

4

Belgian and German historians cooperated after World War II on a better-founded joint account of the most sensational atrocity in Belgium, the destruction of Louvain and the burning of its university library on August 25–28, 1914: see Peter Schöller, Der Fall Löwen und das Weissbuch: Eine kritische Untersuchung der deutschen Dokumentation über die Vorgänge in Löwen vom 25. bis 28. August 1914 (Cologne: Böhlau, 1958). ↩

-

5

Larry Zuckerman, The Rape of Belgium: The Untold Story of World War I (New York University Press, 2004). ↩

-

6

Illustrierter Beobachter, August 24, 1939, pp. 1316–1318. ↩

-

7

Irène Némirovsky, Suite française, translated by Sandra Smith (Knopf, 2006). Her rapid shifts from one family’s story to another, disorienting to some readers, fits the experience. ↩

-

8

Jean-Pierre Azéma, 1940: L’Année terrible (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1990), p. 128; Jean-Pierre Rioux, “L’Exode: mai–juin 1940,” in L’Histoire, No. 129 (January 1990). ↩

-

9

Alfed M. De Zayas, A Terrible Revenge: The Ethnic Cleansing of the East European Germans, 1944–1950 (St. Martin’s, 1994). ↩