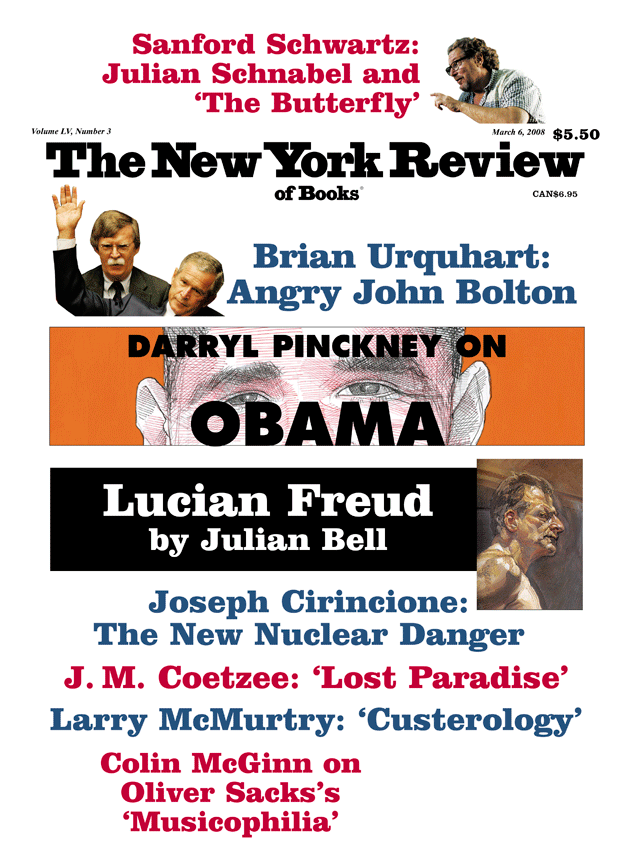

For those of us who have followed Julian Schnabel’s larger-than-life career as an artist for nearly thirty years, watching his new movie The Diving Bell and the Butterfly is a doubly extraordinary experience. It is a film that presents a nightmarish and almost unbearable medical case history that has been handled with humor, a lyrical deftness, and a remarkable absence of sentimentality; and if you have more than a passing sense of Schnabel the person and his work as a painter, your mind is running at the same time on a parallel track, one full of amazement and almost disbelief that, with no apparent training in theater arts or the directing of actors, or even a feeling for photography, he has turned himself into a sometime moviemaker—this is his third film—of such drive and sensitivity. The movie is about a patient’s transformation of himself as he lies in a hospital bed; and it has been made by someone who, with a perhaps related kind of strength, is similarly extending himself.

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly is based on the book of the same name by Jean-Dominique Bauby. The editor of the French fashion magazine Elle, Bauby suffered a stroke at the end of 1995, at forty-three, that left him paralyzed from head to toe and able only to use his mind, to hear from one ear (in a muffled way), to move his head a little (with a huge effort), to grunt out the letters of the alphabet (after considerable therapy), and most crucially to see from his left eye and to blink its lid. A victim of what is known as locked-in syndrome, Bauby learned how to communicate through a collaborative process. As someone read to him letters of the alphabet, he would, through blinking at the letter he needed, spell out words.

When the point of this process became the writing of a book about the experience Bauby was living through and what it touched off in him about other aspects of his life, his condition must have seemed a fraction less unbearable. (He died a few days after his book was published, in 1997.) Although he doesn’t identify himself as a writer, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly is an astonishing report from so damaged and deprived a state of being that most of us resist imagining what it would be like in such a situation. It is also, unbelievably, a wry, tender, and beautifully measured piece of writing.

Knowing how he wrote, a reader can’t help but linger with Bauby’s every phrase. He calls his left eye “the only window to my cell,” and, in one of many lines that are both felicitous and reverberant, sees the sick as “castaways on the shores of loneliness.” He turns over the recent and distant past—“I cultivate the art of simmering memories”—and especially likes to think about food and eating experiences, briskly noting, “If it’s a restaurant, no need to call ahead.”

Schnabel and screenwriter Ronald Harwood have stayed close to Bauby’s way of weaving together his descriptions of hospital routine, his daydreams, and his thoughts about his life before the stroke. One of the best vignettes is about the last time Bauby (the impishly youthful Mathieu Amalric) visited his apartment-bound father (Max von Sydow) and shaved the old fellow. Even better is the tale of a hectic trip he once made to Lourdes with a girlfriend during a frayed time when their relationship was breaking up. Some story elements and characters have been added, presumably for dramatic emphasis, but the filmmakers, following Bauby in his book, effectively wait until nearly the end to place the scene where he has his stroke. He calls the memory of it “this bungee jump into my past.”

More importantly, Schnabel and Harwood, like Bauby, have been able to make the experience of locked-in syndrome be as much about awareness and appetite as it is about imprisonment and helplessness. The movie’s most visually striking and indelible scenes are at the beginning, when the camera shows the gauzy way Bauby, coming out of his coma, takes in his hospital room. The faces of doctors and nurses keep peering into the camera, and when one doctor decides that Bauby’s right eyelid needs to be sewn shut (because it is no longer working as a cover), we feel the needle going right through our lids. In a crafty touch, it takes a leisurely time before we see the patient himself.

The essence of these early scenes is the way Bauby’s eye roams over the greenish hospital room, the hazy pictures on the walls, the curtains moving with the breeze. The breeze is a foretaste of the sea, which has a two-sided presence in the movie. When Bauby feels most helpless and doomed, he sees himself trapped in a diving bell, sinking to a watery end. (When he feels calm and serene, on the other hand, he listens to “the butterflies that flutter inside my head.”) But the hospital he is in is directly on the Channel coast, and going to the shore in his wheelchair, or spending hours on a terrace facing the water, or even, it seems, looking at the curtains stirring in his room are heaven-sent reprieves. When Bauby’s spirits rise we see icebergs melting in fast action, and in a moment the moviemakers invented, and that smoothly blends with the film’s percolating flow of naturalism and fantasy, Bauby is seen, in his wheelchair, on a little platform in the sea, a one-man oil rig.

Advertisement

Like Basquiat, Schnabel’s 1996 film about the painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Before Night Falls, of 2000, about the exiled Cuban poet and novelist Reinaldo Arenas, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly is first and foremost a crisp, craftsmanly piece of work, stylish to the degree that the material calls for it and always driven by the needs of the story. Each of the movies, furthermore, is about an actual person of real accomplishment who came to an untimely death.

And like The Diving Bell, Schnabel’s earlier movies are graced by images of being on, by, or immersed in water. When Basquiat fantasizes about his future he looks up and sees, above the tops of city buildings, a sky that has become one big ocean wave with surfers carving down it. In Before Night Falls, Arenas’s moments of wider understanding, whether concerning his artistic identity, his sexuality, or his political freedom, are inseparable from his being, respectively, in the rain, by a river, or diving into the sea.

The films aren’t all, however, of the same quality. Basquiat, which is set in New York’s early 1980s SoHo art scene, when art stars seemed to bubble up overnight, had to have been something of a trainer film for Schnabel. And whether because of Jeffrey Wright’s subdued performance as Basquiat—he often seems to be retreating into himself or responding only by angling or twitching his hands and body—or to Schnabel’s having taken on too much material (the screenplay is solely his), the movie is more like a careful and sweet-tempered illustration than a penetratingly original view.

Before Night Falls, though, was a huge step forward. It, too, presents a person making his way through a distinct social milieu, in this case Castro’s Cuba during the 1960s and 1970s, when individual liberties were first celebrated and soon eradicated. Based on Arenas’s autobiography of the same title, the movie at its core is an urgent and affectionate portrait of a man who rose from a background of dirt-poor farmers in the hinterland to become an internationally recognized writer—and who was brutally punished for his views by Castro’s regime and eventually died in New York, a decade after he was able to leave Cuba, of AIDS.

Schnabel is as intimate and down-to-earth about Arenas’s life as a homosexual, and about the texture of Hispanic Caribbean culture, as he is about the hospital world Jean-Dominique Bauby inhabits. But Before Night Falls is a richer and deeper movie than The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. It encompasses grittier and more tumultuous experiences and revolves around a person (played by Javier Bardem without, it seems, a false moment) who grows as we watch from a cautious kid to a lovely young man and then finally to a self-assured and hardly cautious lover and writer whose refusal to conform leads to imprisonment and torture. He is a man whom we see repeatedly as a victim and a survivor and who by the end has become, in his ravaged state, living in his West Side walk-up, amid threadbare furnishings, a tragic and commanding figure.

By the end of The Diving Bell, on the contrary, I felt as if Bauby the person, for all that we are constantly in his head, was somehow less tangible than the details surrounding him: his plight; the process by which he communicates; the stimulatingly unpredictable flow of his visitors, dreams, and memories—all presided over by the nineteenth-century hospital he is in, with its sea air and nearby lighthouse. Yet if The Diving Bell is less powerful emotionally than Before Night Falls, it is a more unified and elegant piece of moviemaking. It is closer to a short story than a novel in that its power resides in the way it makes so many feelings grow from and keep circling back to one pinpointed episode.

Different in their weight as Schnabel’s movies are, they would stand as a considerable achievement even if their maker came out of the world of film school, TV, or theater. His having had apparently no experience in those spheres, and the fact that he remains essentially a painter (and occasional sculptor), makes them all the more phenomenal. For many members of the art world, where Schnabel’s work has been met with mixed feelings for three decades now, the movies have been received with a combination of admiration, wonderment over how he has moved adroitly into so different an endeavor, and a feeling, not untouched by condescension, that he has finally found his footing (or, as an artist friend said to me after seeing The Diving Bell, “Apparently it’s easier to make a great movie than a great painting”). My own opinion is that in these films Schnabel is less finding or fulfilling himself than creating additional ways to handle themes he has presented with real power, though more ambiguously, and sometimes all too sketchily, in his paintings.

Advertisement

For young artists, though, and for the wider audience that likes to keep tabs on developments in contemporary art, distinctions between Schnabel the artist and the moviemaker will probably be lost. It has been some time since he was a necessary topic in every art-world discussion. His work has had increasingly less impact in the last fifteen or so years, and pictures from any phase of his career are rarely on view in museums, whether because they can take up too much wall space (they are often ten feet wide or more) or, perhaps, because museum curators don’t feel they are either germane to the present or classics of the recent past. As it happens, his best pictures aren’t even in public collections.

Beginning in the late 1970s and going on for a good bit of the following decade, however, Schnabel was omnipresent. He arrived at a moment when contemporary art had been, for a decade or more, in a state of deep self-questioning. It was a time when modernism, with its progressive and idealistic spirit, appeared spent, heroic geniuses were thought—thankfully for many—to be a thing of the past, and painting, viewed increasingly as purely a product, was judged to be an art form no longer capable of expressing any larger cultural aspirations or doubts. Terrific paintings were being made then, of course, but for many the future belonged to conceptual art, process art, video, and performance art, all of which more readily expressed a skepticism about art in the first place.

Schnabel wasn’t the only young person in the late 1970s and early 1980s who seemed to be pushing out against the judgmental spirit of the time. Almost overnight, oils on canvas, often representational in character (and soon labeled Neo-Expressionist), were in galleries again; and the American art world, which had been largely self-involved for decades, was now facing an influx of forceful young European artists, including Anselm Kiefer, and slightly older ones, such as Georg Baselitz and Sigmar Polke, whose involvement with painting in itself and with the European past were eye-opening. Before he was thirty-five, Schnabel, in New York, anyway, came to epitomize this time of upheaval.

Jumping back and forth from paintings that included representational elements (faces, figures) to works that appeared to be purely abstractions (and yet could suggest silhouetted figures set in open spaces), Schnabel seemed to be blithely turning the clock back to the heyday of Abstract Expressionism, when the artist attacked his blank canvas with no preliminary studies, armed only with a belief that, given his psyche, his materials, and his hand, he could fashion a work that expressed his inner life. Few other painters of the moment were as unpredictable or as far-reaching as Schnabel in the look of their pictures or in the elements that went into their making.

He painted on velvet and old carpets, among other things, and his best-known pictures had broken plates embedded in the oil surfaces. From a distance, the white shards, some sticking out at angles, were like huge flakes of snow. Other works, when not primarily abstract, might include rough-hewn portraits of friends or images from the history of art or from, it seemed, illustrations of legendary tales. A bearded king in his forest domain, a falling Humpty Dumpty (see illustration on page 8), and a rather virile Saint Francis all made appearances.

Schnabel’s paintings were at once touching, bombastic, gorgeously colored, and enigmatic. They had in them elements of boys’ adventure stories, a born memorialist’s love for timeworn textures, and a poet’s feeling for the half-said. His pictures were (and remain) strikingly different from those of many of his contemporaries in that they are hardly one more ironic takeoff on popular culture. They are unusual in having so little to do with sex or politics, or, for an American artist, this or that specifically American theme. They seem particularly unlike American artworks if we consider Schnabel’s complete indifference to shininess and newness in themselves and in his absorption with the old in itself. Encountering a Schnabel can be like visiting the remnant of a tomb from some hazily known culture and era—a site which the corrosions and stray markings of the years have made into something doubly mysterious and even more beckoning.

By 1986, Schnabel seemed ready to be more than an art-world star. From that year and on into 1988, a retrospective of his work went from London to Paris to Düsseldorf, and then traveled to museums in the States, including the Whitney Museum in New York. In 1987, meanwhile, Random House brought out the thirty-six-year-old’s autobiography, a volume with the same portentous sort of title he regularly gave to his pictures: C.V.J.: Nicknames of Maitre D’s & Other Excerpts from Life. At the same time, though, Schnabel’s allure, and the excitement surrounding Neo-Expressionism, were starting to wane. He had always carried himself with a large and sometimes alienating amount of self-confidence, and many viewers were wearied of the way he could seem to be playing at being a modern old master.

Yet even as Schnabel was becoming less central to the art world, his work was getting more tensely ambiguous. In the late 1980s, he was successfully incorporating words in his pictures, whether sayings or names, and he was giving more of a role to the materials he had found to paint on—some of which, including discarded Kabuki theater backdrops, showed landscapes or building façades and were pictures in their own right to begin with. Schnabel was operating a bit like a master of ceremonies. He was producing duets, as it were, combinations of found materials and his own embellishments on them, which left viewers happily uncertain who did what. He was one of the bigger personalities to hit the American art world, but some of his works seemed to be about authorlessness.

With hindsight, Schnabel’s collaborative procedure as a painter seems not all that far from the process of directing movies. And in C.V.J. we see most fully what he means by collaboration in an aside about water and surfing—subjects whose importance to him will be no surprise to viewers of his films. “Being in the water alone, surfing,” he writes, “sharpens a particular kind of concentration, an ability to agree with the ocean, to react with a force that is larger than you are.” Perhaps only Schnabel, with his predilection for grandiosity, would come up with “the ocean” when asked to name “a force that is larger than you are.” Yet the idea of wanting to “agree with the ocean” also encapsulates his range as an artist in any medium.

On and off in his work as a painter, especially in the last fifteen years or so, Schnabel has certainly seemed like a surfer in the sense of someone who glides along on the surface of things. His appreciation for, and ability to conjure up, mouthwatering combinations of colors and textures, allied with his maestro’s certitude that his slightest touch will have a larger meaning, has resulted in more than a few glibly handsome pictures, an impression that has been compounded by his foray into interior decoration. The Gramercy Park Hotel in Manhattan, for whose refurbishment in recent years he was the artistic director, gives a dizzying sense of just how huge Schnabel’s appetite is for life’s goodies and for wanting the rest of us to know about them.

From the door handles on up through the artworks on the walls (which are by him and by artists he presumably admires), and including tables, rugs, and lanterns, Schnabel has been the designer. He has even done the hotel’s logo, composed of the letters G, P, and H, which he has fashioned so that each has its own individualized character. The lettering is of the sort that might be found on a pirate’s map in a novel by Robert Louis Stevenson, and, as in Stevenson, you are transported, walking into the hotel, though whether you have been taken to seventeenth-century Spain (it’s rather dark and drapery-laden), the South Seas (the lamp fixtures inspired by a sawtooth fish bill), Venice (the fantastic glass chandelier), or Morocco (Claude Rains will be waiting for you in the Jade Bar), it is hard to say.

Essentially, you feel you are in the Julian Schnabel Museum of Life, where his imprimatur in the form of his GHP logo might very well be part of the bathrobe you put on after your shower and the linen you sleep on, and the music coming forth from the room stereo will be his programming. Why not? In his movies, Schnabel chooses the always wide-ranging background music, and his sense for when to use, say, Mahler or Tom Waits—or, as in an eating scene in The Diving Bell, a theme from the movie Lolita—is inventive and astute in itself.

The Schnabel who is such a consummate connoisseur and organizer of the sensuous was, it is true, in abeyance in his first two movies. In Before Night Falls, there is a firm balance between the hard-and-fast details of Arenas’s life story and the movie’s visual textures, its sense of place, and its varied soundtrack. In The Diving Bell, though, perhaps inspired by Bauby’s almost involuntary need to hold before his mind’s eye the pleasures he has known, Schnabel the orchestrator of pleasures nearly overruns his material. Unlike Bauby in his book, Schnabel has filled his movie with so many great-looking women—playing Bauby’s therapists, the mother of his children, his lovers—that the film sometimes seems more overripe than rhapsodic.

Yet if Schnabel is a surfer in the sense of knowing how to skim existence for its wonders, he is also a surfer in the more challenging sense of wanting to see where something bigger than himself, or the unknown, will take him, even with the knowledge that he might not come back from the trip. It is this Schnabel who helped instigate the painting revival of the early 1980s, a shift whose residue is the anything-is-possible thinking that has held sway in contemporary art since. It is this Schnabel who had the nerve and the will to plunge into moviemaking when he was in his mid-forties, and to do so furthermore not in the form of videos to be shown in galleries but in full-fledged films for the general audience.

It is this Schnabel, finally, who feels the need to see experience and the sensuous beauty of the world in light of our mortality. His paintings, in which used-up materials are brought back from oblivion, are at their best emotionally replete and formally charged embodiments of this thinking, and his movies, elegies that aren’t maudlin, spell it out.

As statements he has been making about his aims since before he was thirty indicate, Schnabel has long lived with the pressure to acknowledge, as he wrote in C.V.J., those “who watched themselves die, who knew what was happening and knew they had a slim chance.” So it isn’t altogether surprising that he has gotten into Jean-Dominique Bauby’s skin with such seeming ease, and made so fluent a movie out of a book that, on the face of it, hardly seems as if it could be filmed. Schnabel is in his way just the person to make us see what it is like to take in the world for one last time.

This Issue

March 6, 2008