In response to:

Infiltrating the Enemy of the Mind from the April 17, 2008 issue

To the Editors:

I read with great interest Jay Neugeboren’s review of Elyn Saks’s The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness [“Infiltrating the Enemy of the Mind,” NYR, April 17]. When I was a resident in psychiatry at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, during our rotation through the Bronx State Hospital our mentor Dr. Ed Hornick used to invite a patient in from the joint staff/patient daily group meeting to offer a critique of our performance. He also required each of us to take one patient from the so-called “backwards,” people with chronic schizophrenia who sat for years doing very little, and treat them with “talk therapy.” We were amazed that not one of us failed to return these patients to the community, much like Robert, the reviewer’s brother. Alas when we checked in on our patients after discharge from our care and we had moved on to another part of the program, all of them had quickly relapsed.

On another point, the wonderful therapist Frieda Fromm-Reichman, whose humanity and caring come through in her willingness to go where her patients were (an example in the popular literature can be found in Joanne Greenberg’s novel I Never Promised You a Rose Garden), also gave us the mistaken etiologic idea of the “schizophrenogenic” mother. Her successes probably suggest that the relationship in some nonspecific way focused as Elyn Saks’s analyst did on the “deepest sources of…anxiety.” Other psychotherapists (systems theory family therapists) then developed the notion of the “double-bind” in family communication as causative in schizophrenia. We now know that this is probably a misdirection of the causal arrows, but that family therapy that teaches the creation of a positive and nurturing home environment works at preventing hospitalization. If only Robert’s family knew how important their presence was for his well-being. I went on to become a child psychiatrist and while many of us need to spend a lot of our time prescribing medications, the rule in our clinic is that no child is seen for medications without also being in talk therapy.

Herbert Schreier, M.D.

Department of Psychiatry

Children’s Hospital Research Center

Oakland, California

To the Editors:

The article “Infiltrating the Enemy of the Mind” touched me profoundly because I’ve this enemy in my mind. At the same age as Elyn Saks I was diagnosed with schizophrenia thirty-three years ago. Thanks to shock antipsychotic treatment and supportive psychotherapy I have had a quite “normal” life. I agree with Elyn that neuroleptics alone are not enough, and talk therapy is necessary for most patients—I’ll say crucial. In my case, the possibility of devoting my professional life to artistic occupations, basically painting and literature, has also been very helpful to maintaining an active and deep mental life, hope, strength, and to making sense of reality. Another important point has been religious faith. Without all that, the pharmacological treatment alone would have failed, as Jay Neugeboren exemplifies in the case of his brother, illustrating what happens when treatment lacks psychotherapy. Thank you for your insightful contribution. Schizophrenia is a horrible illness, but nowadays I can say it is possible to have a “friendly” relationship with this enemy of the mind.

Joaquim Pijoan

Barcelona, Spain

Jay Neugeboren replies:

Dr. Schreier notes that with the help of talk therapy, he and his fellow residents were successful in enabling patients with chronic schizophrenia to return to the community, but that their sojourns there were short-lived. He does not tell us, however, about the kinds of treatment, if any, these patients received after they were discharged from the state hospital: Did they see a psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker regularly? Did they have any kind of sustained talk therapy? Were they enrolled in community mental health programs, or were they left on their own?

My own experience suggests that for most patients with chronic schizophrenia who are returned to the community, treatment is largely disorganized and custodial, consisting of behavior modification programs that emphasize compliance with medications; back-to-work programs that are little more than the old sheltered workshops done up in community-center garb; and “recovery” programs that are underfunded, understaffed, and which lack the ability to provide anything resembling continuity of care. Generally, even in the kinds of well-run programs Robert has been part of, there are, as his psychiatrist noted, “no resources” for any kind of talk therapy. But for people who, because of their conditions and history, already have a fragile purchase on the world, how much more important is it that they have somebody—a professional—who can, over time, create that state of trust that will be essential (as it is for all of us, with or without mental illness) when the dark clouds of life roll in and overwhelm.

As Elyn Saks so beautifully demonstrates, we all need, and cherish, the feeling of safety that comes from knowing someone who knows us and cares about us. For most mental patients, however, such a relationship is the rarest of commodities. Even when community centers, mental hospitals, and residences try their best, they are usually compromised by inadequate budgets in which pills—the ultimate downsizing of care—become the primary, and often sole, form of treatment. Consider: in one six-month period, my brother had seven different social workers assigned to him.

Advertisement

Dr. Schreier notes the importance of family. Because families and friends tend to abandon those who suffer from long-term mental illness, however, more important would be the presence of a professional—psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker. This person could act as a skilled, compassionate, and informed guide, short- and/or long-term, to those who struggle with the debilitating effects of mental illness, and with the equally debilitating effects of its treatments—the horrendous side effects of medications, and of the stigma, shame, and isolation that invariably come with having a mental illness.

“It may seem strange to say this of a profession regularly accused of vanity and self-importance,” Dr. Leston Havens, director of adult psychiatric residency training at Harvard Medical School, writes,

that many professional people allow themselves to come and go among patients as if their knowledge and skills were all that counted, their persons not at all. One sees this most vividly with medical students, who cannot believe in their importance to the people they take care of. Yet we are the great placebos of our pharmacopeia, and the power of the placebo can be measured by the results of its withdrawal.

Joaquim Pijoan’s touching letter echoes many other responses I have received from readers: that while medications can be helpful in the treatment and amelioration of mental illnesses, medications alone, without some kind of talk therapy, often prove inadequate. The benefits that derive from a sustained therapeutic relationship are often crucial, not only to recovery from crisis, but to quality of life, in good times and bad, for people like Elyn, my brother, and Mr. Pijoan.

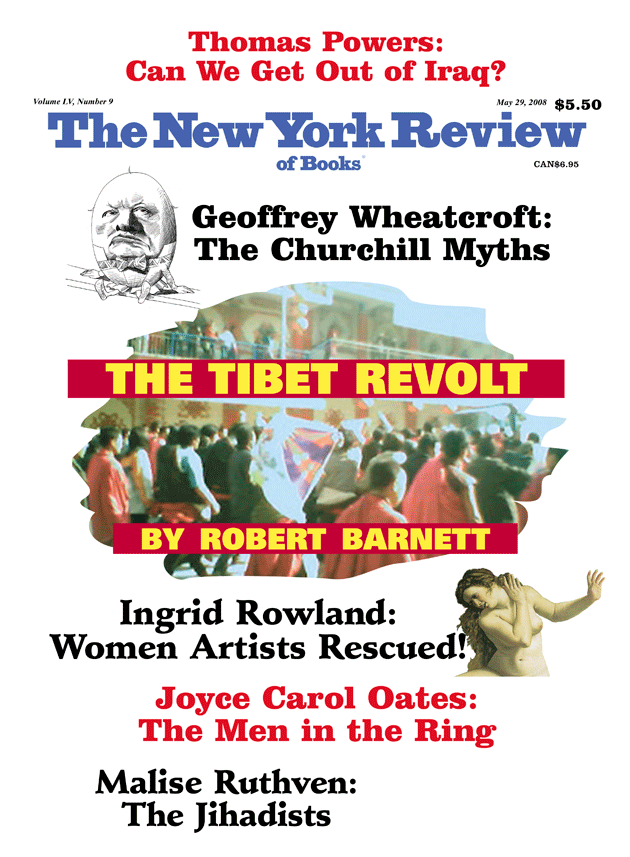

This Issue

May 29, 2008