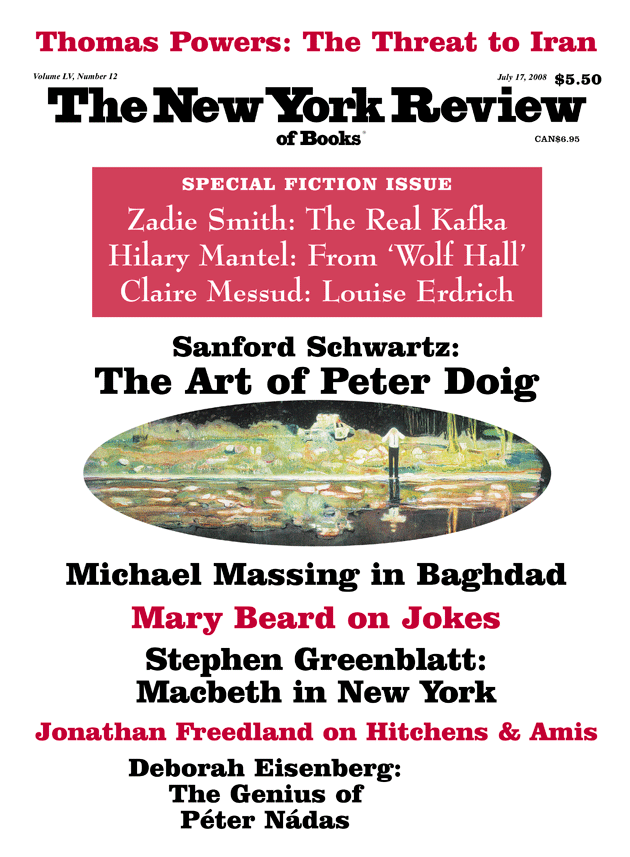

Peter Doig has been seen in a few solo and group shows in New York, Chicago, and Santa Monica over the past fifteen years, but for most Americans who follow contemporary art he remains a hazy figure whose work has been more talked about than viewed. Yet while the artist, who grew up in Canada and has lived in London and Trinidad, hasn’t been seen here in full force (or perhaps because of this), he has attracted a certain following, especially among people chiefly involved with painting. A little bit like Eric Fischl in the early 1980s—in his canvases showing adolescents and adults in sometimes uncomfortably intimate domestic scenes—Doig, it is clear even from reproductions, has been finding ways to make strikingly new kinds of images using age-old themes and materials. It is unfortunate that Tate Britain’s recent survey of the forty-nine-year-old artist’s work couldn’t include an American stop on its tour.

Doig first became known in the early 1990s for paintings of lakes and houses, sometimes seen in snowy, wintry conditions. Later in the decade, he opened up his northern, winter realm to include views of farms, ski runs, and fairs. Even when his substantially sized paintings (about eight feet wide on average) were of summer or autumn scenes, they conveyed roughly the same effect of snow busily falling in every direction. You didn’t just see a canoe on a lake or a house by the side of a road—you saw that subject through a tingling mass of small but distinct details and touches. If Doig’s scenes called for trees or vines, it seemed as if every twig and tendril was presented and felt for itself, becoming almost an abstract web through which we looked to the scene behind it. And while his colors, textures, and forms generally were naturalistic, he could go to wildly fanciful extremes with them, turning the rectangular shapes of a brick wall, for example, into so many little fevered, blotchy abstract paintings.

Adding to the charge of Doig’s paintings was the way they seemed to refer to earlier art without in the process becoming musty or derivative. Swamped (1990), an image of a canoe on a lake which may be an ultimate presentation of a lake’s bubbly, branch-clogged texture, had the crackling intensity of a Jackson Pollock. Doig’s forest pictures, with their sense of distant light cradled by dark trees, recalled Munch, and his way of getting carried away with carpety and lichen-like zones of pure texture brought Vuillard to mind. Yet the world Doig presented was surprisingly of the moment. His pictures suggested something of the loneliness of adolescence and the grubbiness and vague threat of rural places that outwardly have a postcard-like prettiness.

In his images of boys in parkas whiling away gray winter afternoons by iced-over ponds, of skiers and skateboarders, of country houses that we suspect are as dank and disheveled inside as they are romantically enveloped by trees on the outside—and, from later in the 1990s, of a policeman and a black-and-white cop car by the side of a lake—Doig caught aspects of contemporary life that, although they appear in photographers’ work and in movies and on TV, seldom appear in paintings. They are seldom the subject, that is, of paintings that, like Doig’s, are so large in their literal size and ambition.

At the Tate’s show, which included work from 1989 to 2007 (and is now on view in Paris), Doig’s paintings of the early 1990s were as scintillating as this viewer, at least, had expected they would be. In their ecstatic abundance of intricate brushwork, misty sprayed-on areas, and creamy dots of paint flung on for finishing touches, pictures such as Swamped, Baked (1990), of a body of water seen at a hallucinatory moment when every form is either red or black, and Pond Life (1993; see illustration on page 8), of a house and people viewed through a maze of iced-over branches, are like reinventions of the idea of landscape. Often set on water, and showing us worlds where forms appear twice, right side up and upside down, many of these early paintings draw us, like photographs of twins, into trance-like states where we can’t help but go back and forth between shapes and their doubles. Few pictures that Doig went on to make are at once so everyday in their subject matter and so brilliantly artificial in their appearance.

This doesn’t mean that everything he did after the early 1990s is exactly anticlimactic. Since that time, Doig has gone from scenes of country life at different times of year to equally enigmatic, although more somber and moody, pictures of, to take some examples, a basketball court when no one is around and an empty, almost derelict room in a modernist apartment building. Gasthof zur Muldentalsperre (2000–2002), a panoramic view of a dam and a lake at night, attended by two gatekeepers in exotic costumes, is a majestic and magical work that somehow unites landscape art, stage design, and children’s book illustration. Doig’s thinking about the appearance of a painting has changed, too, from wanting the surface of his picture to be as complicatedly built up as possible to the opposite—where oil is put on so thinly we feel at times we look at huge watercolors.

Advertisement

In recent years, the artist has been living in the Caribbean, and his pictures, including one of an old horse and some birds by a glassy pool of water on a seemingly torpid day and another of a dreamy view through a curtain to a tropical vista at night, seemingly reflect his new home. Although there has been a gradual dimming of intensity over the years, and there is a hollowness to some of his more recent efforts, Doig has made first-rate paintings on and off for nearly two decades. The full range of his work, furthermore, presents a more shaded and complex experience than one might have expected.

Doig is not clearly identified with any art movement, but he shares a certain resemblance with a number of painters who were born a few years apart in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Among them are the German Neo Rauch, the Belgian Luc Tuymans, the Welshman Merlin James, and the American John Currin. They are outwardly on firmly separate tracks, but they are all representational painters of a sort who came to maturity in the wake of artists such as Anselm Kiefer and David Salle—artists who, in the early 1980s, made the art world take painting seriously again after many years during which the form had seemingly lost its purpose and punch.

Doig and Co. (if they can be called that for a moment) found their voices, in other words, when, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was less pressure for a painter to prove his or her right to the art form in the first place and perhaps more freedom to experiment, to make of painting a more private, personal realm. These artists were able, if they wanted it, to connect their work with painting from earlier eras, whether from many different historical periods, as Merlin James has done, from Cranach’s time, as John Currin has done, or from the Post-Impressionist 1890s, which seems to be one of Doig’s chosen moments. Yet even as Doig and the others have let earlier painting approaches echo through their work, they grew up when abstract and later minimalist and conceptual art reigned, and the representational pictures they have made are informed almost as much by ideas that question representational painting as glorify it.

Among these artists of the 1990s, Doig may be the most difficult to sum up. While he is a master at presenting different kinds of atmosphere, place, and light, he can also be involved with the tricks and uncertainties of seeing. The marvelous Jetty (1994), for example, which shows a tiny man on a lakeside dock with an immense mountain rising up from the opposite shore, is like a photograph taken with a telephoto lens (and like Klimt’s lakeside landscapes) in the way vastness and distance have been made to seem unnaturally close and evenly, airlessly flat. Disturbingly, the sharply focused outline of the man, in contrast with the shimmeringly unfocused rest of the picture, makes us feel we are not so much looking at him as taking aim at him with a rifle.

Yet much of the time Doig’s principal concern seems to be the rapport he sets up with the materials of his craft, whether he is making paintings in his piled-on and filigreed early manner or wants painted surfaces to be vaporous and impalpable. What makes so many of his pictures mesmerizing has to do with his seemingly spontaneous outbreaks of decorative detailing—when, in Gasthof, he treats each tree as if it were a single, big, blotted-out leaf, or dresses up a humdrum country house as if it were a birthday cake, or presents a row of trees by a ski run with the flatness of a silhouette, all painted red (Neo Rauch, as it happens, has treated whole forests the same way). And while one might have thought, from Doig’s early pictures, that he was a sort of naturalist and lyric visionary, his art, seen in full, leaves an impression, too, of bruised and hidden feelings.

Doig’s biography mirrors the lack of boundaries that characterizes his paintings. It is hard to say even what his nationality is. He was born in Edinburgh and his parents are Scottish. When he was two, however, his father’s work in a shipping company took him and his family to Trinidad (Doig senior had himself been born in Sri Lanka), where they lived for five years before being relocated to Canada. There, first in suburban Montreal and later in rural Ontario, Peter Doig spent his boyhood and adolescence, although his family was never in the same place for more than two or three years.

Advertisement

In 1979, he left for London—because, he has said, this was where the new music he liked was being made— and a stay in art school. By 1986 he was back in the Montreal area, where he remained for some two years—taking on board, as it were, the sensations that, when he returned to London in 1989, gave him the material for his breakthrough pictures, which he began making that year. In 2000, an extended stay in Trinidad apparently made Doig believe that he might not always live in London, and in 2002 he moved with his family to the environs of Port of Spain, the country’s capital.

The many addresses Doig has had would seem to explain the dramatic shifts in his imagery and his desire to capture the precise crunchy wetness of snow or the precise wiltedness of a West Indian riverbank. When Doig’s early images of lakes and ski runs were becoming known, one felt, in addition, that a particularly Canadian note had been captured on canvas. Doig seemed to be giving an expansiveness and a psychological ramification to the landscape art of David Milne, one of the most assured and distinctive Canadian artists of the first half of the twentieth century. Milne’s lakeside scenes, with forms and spaces repeated because of the water’s reflectivity, and painted with innumerable small touches, are true forebears of many Doig canvases.

It is worth noting, however, that Doig, who works from his own photographs and from photos he finds (and likes to arrive at his chosen image through studies in many mediums), isn’t always concerned that the memory or experience he shows is his own. Some of his more “Canadian” images —including Swamped and the related pictures of a canoe drifting on a lake— come from Sean Cunningham’s 1980 horror movie Friday the 13th, which was shot in Blairstown, New Jersey. Young Bean Farmer (1991), an image that this viewer believed might be of some archetypal Canadian or perhaps midwestern American farm, derives from a photograph in a 1984 National Geographic article on Pennsylvania Dutch country. The vast Ski Jacket (1994), which comes across as a kind of summary of a Canadian or possibly American pastime, is based on a photograph of a Japanese mountain hotel, and a close look shows most of the skiers floundering. But perhaps the greatest instance of Doig’s need to work at a remove from his subject is the fact that a number of his images that we associate with Trinidad come from postcards of southern India that he found in London.

Although it doesn’t bring the many aspects of his art neatly together, and perhaps is an odd and pejorative-sounding way to describe paintings, I think that Doig is a maker of fairy tales of a sort. His best pictures, anyway, have the equally enchanted, forlorn, and ominous spirit we associate with fairy tales. And in this regard it is fascinating (although not, admittedly, pure pleasure) to see the film Friday the 13th, perhaps Doig’s single greatest quarry for images. It is hardly breaking news that painters have long worked from one photographic source or another, including movie stills; but Doig’s connection with this horror movie has an unusual, even daring, intimacy.

The film is about a cursed summer camp and the deaths of all but one of the counselors on a day shortly before the campers are due to arrive. It is a cheesy but taut, all-business slasher, full of shots where the killer, whose face we haven’t as yet seen, spies, through tree boughs, rustling leaves, and railings, on the various prospective victims—shots that recall any number of Doig’s paintings in which we look through branches or falling snow to a scene beyond. Toward the movie’s end, however, there is a sequence, only minutes long, which those familiar with Doig’s work will watch with open-mouthed wonder.

The lone living counselor has, she thinks, done in the killer, and, unable to bear any more of the camp, she has spent the night in a canoe, adrift on the lake. Now, at the beginning of the (wordless) sequence, it is a lovely new day, and, accompanied by flowing, lyrical music, in itself unlike any music in the movie so far, we are given different shots of the boat, reflections of light on the water (which the camera registers as blobby, swirling, abstract shapes), and the arrival of the police. One of them comes down to the lake, raises his hands to his mouth, and calls out to see if anyone is in the canoe.

And with shot after shot we look at one Doig painting after another: his images of a canoe where a little figure is barely visible in it; a painting where we see a woman in a canoe with her hand in the water; pictures where he employed the same blobby white shapes that the camera picked up when it recorded the water’s reflectivity; and then Echo Lake (1998; see illustration on page 6), where a policeman by the water’s edge cups his hands to his mouth and calls out.

Watching this part of Friday the 13th in light of Doig’s work, we can be startled or angered by his audacity. Considering that he made paintings from these movie images on and off between 1989 and 1998, we can also wonder at the spell the sequence put him under. Part of its power no doubt was its conclusion. The music stops, and in true horror-movie style the counselor learns she is not alone on the lake. We have been watching, of course, a kind of false ending. It is that prolonged moment of relief and resolution that exists in order to make the following onslaught all the more terrifying.

Many of Doig’s paintings are versions of such ambiguous moments. It is not that he wants to make paintings that are the equivalent of ploys or false endings. It is that he creates scenes where a defining act has happened or will happen, and what we take in is an indirectly tense coda or prelude. Besides, the sequence in Friday the 13th that so caught his attention isn’t entirely false. It leads to a nightmarish end but before it does so it provides a genuine sense of release.

Right now, however, Doig is in a shaky place. He is increasingly bringing the human figure into his pictures, and the evidence of all his work suggests that this is something he has long been cautious and uncertain about and still hasn’t mastered. His early pictures are actually quite populated but in appealingly devious, almost secretive ways. In Swamped, we can easily miss the little person slumped in the canoe. In Young Bean Farmer, the protagonist is merely a blur. In other pictures people are so tiny as to be barely recognizable, or someone is spookily present as little more than a reflection in the water. An artist out sketching is blended, like camouflage, into the landscape, as is the faceless cop in Echo Lake. In Orange Sunshine (1995–1996), which unfortunately is not in the show, a skier flying through the air is painted so that his or her flat, silhouette-like shape virtually disappears into the sun and clouds.

Doig has wanted to make his newer figures more prominent, and these characters include a child standing high up in a tree, a man who seems to be turning into a bat, and a bearded, hippieish fellow going by in a canoe. More like personifications of occult, even ghostly, forces than specific people, these figures are less felt than the skiers and canoeists and winter walkers in his earlier works whom we were at first barely aware of. It is clear that Doig, who is as much of an explorer of new regions in his art as in his life, is looking for a bolder, more immediate way to present the disquieting spirit that underlies his work. So far, though, that spirit has come across most fully when, as with the camp counselor drifting on the lake that morning, it takes a little time to be announced.

This Issue

July 17, 2008

His Royal Shyness: King Hussein and Israel