The Snow Leopard is an account of an expedition high into the seldom-seen Himalayan land of Inner Dolpo, to record the habits of the bharal, or rare Himalayan blue sheep, and, if possible, in passing to glimpse the famously shy and evasive snow leopard. The book, which is just being reissued by Penguin Classics, begins, as most scientific logs do, with a precise map, and ends with scholarly notes and an index. The leader of the climb is the eminent field biologist George Schaller (here known as “GS”) and with him travel various local porters and Sherpas and the writer who records the trip, Peter Matthiessen. The author, a “naturalist, explorer,” as his bio has it, takes pains to note every “cocoa-coloured wood frog” the travelers pass, and the “pale lavender-blue winged blossoms of the orchid tree (Bauhinia).” He records altitudes and temperatures and the history and geography of every region he visits. The human habitations he describes are, typically, full of “vacant children, listless adults, bent dogs and thin chickens in a litter of sagging shacks and rubble, mud, weeds, stagnant ditches….”

Yet even as it makes us feel every pebble and rag on the tough journey, The Snow Leopard is the record of a different kind of ascent as well, which the reader catches as a silent current pulsing just beneath the lines. “I climb on through grey daybreak worlds towards the light,” its author tells us at one moment, and a little later he is in a world of “snow and silence, wind and blue.” The journey is clearly to places inward as well as up, and as the author climbs and climbs toward his final way-station, at 18,000 feet, near the Crystal Mountain, he seems so to disappear inside the vastness of the scene around him—the sharpened skies, the deep blue silences, the elegant clarity of a world of snow and rock—that it begins to feel as if those forces are speaking as much as he does. “The earth is ringing. All is moving, full of power, full of light.” The book is written, you begin to sense, by a serious self-taught scientist (who spent most of a year driving around his country and producing a near-definitive book, Wildlife in America ). But it is also written, in the same breath, by a Zen student who will later become a priest, whose business it is to see past all the projections and delusions of the mind to the hard rock of unvarnished reality. It is written by a seasoned journalist of the old school whose range is so great that he can light up the paths he is taking by referring to Blake and Heisenberg and Sufi and Native American lore, drawing his epigraphs from a Hindu priest, a modern lama, Hesse and Rilke and Ovid; but it is, in those same sentences, being written by a novelist who seeks to track the nature within us as well as without, and, indeed, to link the two. The ascent is an attempt to chart what cannot be seen and recorded, and the sense of elevation we feel on reading the book is the one we know, perhaps, when we close our eyes and just sit still. What comes to seem remarkable, and haunting, about the book has little to do with the fact that few travelers had been to Inner Dolpo in 1973, or even that no one, Peter Matthiessen suggests, had ever recorded the voice of the blue sheep before he did, as he’s observed by the animals from a distance of ten yards. It comes, rather, from the sense that we feel, with him, the pulse-quickening sense of discovery that arises when you come upon passes and places that have almost never been seen before; and yet, in that very moment, you also feel a sense of loss—that excitements fade, that everything moves on, that animals and forests will soon be no more, and that even the epiphanies and discoveries that seemed so exhilarating yesterday will very soon be forgotten. If you visit the high plateaus of the Himalaya—moved, perhaps, by the book to do so—you come upon great many-storied buildings on the hilltops that look out across the emptiness like fortresses and watchposts both at once. If you step into their chapels, you smell centuries of melted yak butter, make out frescoes barely visible in the faint light, feel coldness on the bare floors. The sun comes in shafts through the dust, lighting up the Buddhas. And as you walk around these cities on a hill, you begin to notice that each level is linked to the next by a short, steep ladder. You climb up, through terraces, past kitchens and altar rooms and schoolrooms, till finally you come to a flat rooftop from which nothing can be seen or heard but the snapping of prayer flags in the wind, the blue skies extending all around, the snowcaps in the distance. You have entered, as The Snow Leopard shows us, a realm of allegory.

Advertisement

When I return to Peter Matthiessen’s silver account today—noticing how it grows as I do, giving back a different light every time I pick it up again—what I feel most is the sheer physicality of the climb, the return to something bare and essential behind or beneath the realm of thoughts. The author crops his skull as he sets out, and begins to walk barefoot as he leaves the world of roads. He makes me feel and flinch from the blisters on the climbers’ feet, the leeches on their skin. I shiver, such is the transparent immediacy of the prose, when the temperature sinks to –20 degrees Centigrade, and feel with the author how “I quake with cold all night.”

Part of the beauty of such a trip is that it permits few vanities: the writer is reduced to scrambling on all fours and watches himself laboring under sixty pounds of lentils. He starts to go to sleep at nightfall and to awaken with first light, like the living things around him. His porters, at one precipitous moment, give themselves over to a silent trance. The trip is not taking him away from the real world, so much as deeper into it, the better to feel its sting; epiphanies, after all, are the easy part—it’s the acceptance of the everyday that comes hard. Yet always there is something pricking at the corner of the sentences that suggests a deeper trip. The first day the expedition leaves town, Matthiessen spots a corpse; he has come to Nepal by way of Varanasi, the ancient city in India where dead bodies are committed to the holy waters of the Ganges. Very soon after that, “I nod to Death in passing, aware of the sound of my own feet upon my path.” One reason he has come on this journey, we see tucked into a tight-lipped sentence, is that his young wife, Deborah Love, has died of cancer the previous winter. So as the climb proceeds, it becomes a trip into an understanding of the reality and suffering that lie at the heart of the area’s philosophy. Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, was born just thirty miles from where the travelers pass, and he, too, was a “wanderer,” the author tells us, whose path took him into “the unsentimental embrace of all existence.” The Buddha had his first prompting toward awakening, we may remember, when he stepped out of the gilded palace in which his father tried to keep him, and encountered the abiding human truths of sickness, old age, and death. Very soon, therefore, as the landscape begins to empty out—no roads, no watches, no reminders of the modern world—it becomes clear that the “path” Matthiessen describes is not completely unrelated to the paths of which the Buddha spoke. The journey will be not just a training in attention—and a hard slog—but an instruction in surrender. Matthiessen is not a “seeker,” he reassures us, and he seems much too observant and unsparing to entertain romantic notions of a never-never land. Yet he is honest enough to acknowledge that he hears, every now and then, intimations of another world. “From the forest comes the sound of bells.” At another point he notes that the things he’s carrying along with him are “a dim, restless foreboding” and occasional glimpses of “the lost paradise of our ‘true nature.'”

“It is not worth the whole to go round the world to count the cats in Zanzibar,” Henry David Thoreau famously said, after completing his long journey to (and in) a place only one and a half miles from his home; you do not have to know that Thoreau helped bring Buddhism into America—through the Lotus Sutra whose translation from the French he oversaw in 1844—to see that Matthiessen is walking, to some degree, in his footsteps. Why go round the world to count the cats in Inner Dolpo—especially if, like this author, you are not a field biologist who has a professional need to do so, or a porter who can make a living only by carrying heavy loads?

Yet as he climbs, he begins to think back to the wife he’s just lost, to the Zen discipline she introduced him to. He starts to look at the very tendencies in himself that he might be inclined to sidestep or cover up at home. It quickly becomes apparent that this author is in no hurry to gloss over anything in the inner, or outer, landscape. He wishes to push his friend GS, a famous naturalist, off a cliff at one point; he presents himself more and more as just a “haunted animal,” who confesses, “my legs refuse to move and my heart beats so that I feel sick”; he even admits to a spiritual ambition, the hope that at some point he will come upon some magical teacher or revelation that will lay bare for him the secrets of the universe.

Advertisement

At one moment Matthiessen recalls his eight-year-old son back home, and quotes a letter—a touchingly charming letter—from the boy, Alex, who signs himself “Your sun.” When Matthiessen had decided to take off into the Himalaya, his little boy’s response had been “Too long!” and he had begun to tear up in spite of himself. The eight-year-old has already lost his mother, suddenly; now, he might reasonably feel he’s losing his only other parent. Matthiessen tells his boy that he’ll be back by Thanksgiving. Yet as the journey progresses, we notice that the days are flying by and there is little hope of Matthiessen returning in time to spend Thanksgiving with his son. The quest for understanding has caused him to do one of the most difficult things a parent can do, which is not just to leave behind a child in need but to keep that child waiting. Matthiessen’s trip, we begin to feel, will have to involve some very great revelations indeed in order to justify that let-down. I have met a few readers over the years, especially mothers, who remain upset by that revelation, and choose not to recall that one of the hardest things about the Buddha’s devotion to the truth is that he had to leave his beloved wife and son behind. Yet what moves me, every time I read the book, is that Matthiessen elects to include in his story a letter and a moment that will show him in an uncomfortable light. Most travelers are guilty of a kind of infidelity when they leave their homes and the people closest to them in order to undertake a long and perilous journey—and almost all of them (I know as someone who writes about travel myself) choose to keep out from their records the less exalted, human trade-off. We like to present ourselves as conquering heroes or lone wolves; we will use any literary device we can to keep out of the text the ones waiting for us at home, or the truth of what is always an uneasy compromise. Matthiessen, by contrast—and this is part of the honesty and unflinchingness that I take the book and the climb to be about—tells us whom he’s letting down. He notes, unsentimentally, that he and his late wife had come close to divorce only five months before her death. And as the climb goes on, he keeps thinking back to Alex and Deborah, more and more, sees his boy dressing up (as a skeleton) for Halloween, is suddenly taken back to him even when he hears a woodpecker. Part of the tension of the book comes not in wondering if the team’s provisions will run out, if the passes will be shut off by snow, if the porters will return—though all are real and vivid dangers—but in seeing what it is Matthiessen will find to bring back to compensate for his delayed return.

The Snow Leopard is a liberating book, in fact, in part because it is not about ordinary goodness. It features some of the most transcendent, crystalline moments in modern prose, and yet it is, at every turn, about anger and pain and fear, and its protagonist is as impatient and far from Buddhist tolerance on his way down from his transcendent moments as on his way up. In that sense, it’s a journey into humanity, which Matthiessen is wise enough to see as lying on the other side of the mountains from sainthood (courage, as they say, refers not to the man who’s never scared, but to the one who’s scared and yet braves the challenge nevertheless). In all these regards, and as part of the doctrine of hard realism, it is only right that the door to the Crystal Monastery is locked when Matthiessen arrives, that the lama whom he has been longing to meet for so long turns out to be “the crippled monk who was curing the goat skin in yak butter and brains” that he walked past, and that it is only after the mists clear and his spirit, so he writes, is focused by the Crystal Mountain that “I feel mutilated, murderous; I am in a fury of dark energies, with no control at all on my short temper.”

It is in that context that the most powerful character in the book is the stealthy, unassimilable presence among the party known as Tukten. A Sherpa among the porters, a spirit that no one is entirely comfortable with, a man who has the feel of a sorcerer and is accused of being a thief, Tukten is the most slippery and unsettling presence in the mountains, whose air of threat sometimes seems more charged and intense than that of the elements themselves. And yet he is the author’s shadow, and, you could say, familiar. He is “somehow known to me, like a dim figure from another life,” and the two of them seem linked, always aware of where the other is. Milarepa, the great poet-saint of Tibet, was said once to have converted himself into a snow leopard to confound his enemies; reading Peter Matthiessen, we begin to suspect that a snow leopard like the one he hopes to see has chosen to turn himself into Tukten, who always remains solitary and unknowable, “the most mysterious of the great cats.” Matthiessen even calls Tukten—twice—“our evil monk,” the “our” perhaps the most unnerving word of all (“This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine,” as Prospero says of Caliban). Tukten appeals to Matthiessen, even perhaps teaches him (more than does the obviously wise but matter-of-fact lama of Shey) by taking everything in his stride, as the way things are; he will look unmoved, Matthiessen says, on “rape or resurrection.” Not the least of the charms of the book is how the author, who never gives himself the last word and who shows himself in all his foolishness and unfairness, is constantly learning from the people around him—noting how GS happily devours his last ration of chocolate, even as the author is protectively holding on to his, registering how a Sherpa, when his pack falls into a river, greets the catastrophe by laughing aloud. The lessons of the journey into the Himalaya come not just from the famously uplifting mountains, but from the fallen but steadfast, practical, down-to-earth people who walk among them. The central feature of the practice of meditation and hard work known as Zen is that, as Matthiessen says, it “has no patience with ‘mysticism,’ far less the occult.” Nor does it have any time for moralism, the prescriptions or distortions we would impose upon the world, obscuring it from our view. It insists that we take this moment for what it is, undistracted, and not cloud it with needless worries of what might have been, or fantasies of what might come to be. It is, essentially, a training in the real, what lies beyond our ideas (and they are only ideas) of good and bad. “The Universe itself is the scripture of Zen,” as Matthiessen puts it, and the discipline initiates its practitioners in the clear, unambiguous realization that what is, is; the world (enlightenment, happiness) is just that lammergeier, or bearded vulture, in the sky, this piece of dung, that churning river, all of which have life and blood as our perceptions of them do not. In that regard, The Snow Leopard records the story of a journey into precision, and all that lies on the far side of our thoughts, our ceaseless chatter. Up near the Crystal Mountain, creating a homemade meditation shelter for himself (and as he has said earlier, sometimes pushed to do Zen practice just because it is so cold), Matthiessen enters at last a moment that seems to open up unendingly. “These hard rocks instruct my bones in what my brain could never grasp.” This involves, as he writes of the Buddha, a deeply unsentimental embrace of all existence: prayer flags are “worn to wisps by wind,” the lama is dressed in “ancient laceless shoes” and a jacket “patched with burlap,” feasts in this barrenness consist of “sun-dried green yak cheese,” but for those few days in a “world above the clouds”—not having seen a mirror for weeks—the author enters a world that can’t be argued away.

It can be so startling to enter this world that is at once as real as this blister and a subtle allegory that it is easy to overlook the extraordinary care and craft that underlie the book. And that is fine. William Shawn’s New Yorker, which sponsored most of Matthiessen’s natural expeditions, including this one, encouraged its writers to pay attention to the world they were reporting on, and not themselves; Zen does much the same, making the ego seem small and laughable in the context of the natural facts around it. The point of The Snow Leopard is, much more than in most books, to lose sight of the author and his language so as to feel the silver light of the mountains, the blue sky opening above, the silence and the clarity.

Yet look more closely at the text and you enjoy a different kind of wonder, akin to the one the author feels in reading every fig tree and macaque. Early on in the narrative Matthiessen writes of how rain “comes and goes.” Roughly fifty pages, and many lifetimes, later, the sun “comes and goes.” This stands for the changeable condition of the elements in the high mountains; everything is ephemeral. Yet you also notice, if you’re paying attention, that the phrase itself keeps coming and going through the book and, a little later, “tears and laughter come and go.” It hardly matters that “coming and going” is almost the first principle of Zen, the phrase you find in every Zen master’s haiku; the point is that the words themselves tell you not to take the mood too seriously. “I don’t trust my inner feelings,” as Leonard Cohen writes in a late song, having lived as a Zen monk on a lonely mountain, “inner feelings come and go.” “There is no wisp of cloud—clear, clear, clear, clear,” Matthiessen writes at another point on the high mountain. A less confident writer would have tried to decorate or vary the sentence, would never have had the courage to repeat the same simple word four times, as if to take you to a place where all words give out. “It is the precise bite and feel and sound of every step that fills me with life,” Matthiessen writes elsewhere, and the reader might notice how it is the precise monosyllables—the strict bark of “bite and feel and sound”—that fill the prose with life.

You can enjoy The Snow Leopard without responding to any of this, and yet, if you are so inclined, The Snow Leopard offers a kind of handbook on how precision and modesty work, and how contemporary, immediate language can echo the sound of ancient verses. Perhaps my favorite moment in the entire work comes when Matthiessen writes, “I grow into these mountain like a moss. I am bewitched”; and then, after the two short, simple sentences beginning with “I,” there comes a rolling sentence that takes in the

blinding snow peaks and the clarion air, the sound of earth and heaven in the silence, the requiem birds, the mythic beasts, the flags, great horns, and old carved stones, the rough-hewn Tartars in their braids and homespun boots, the silver ice in the black river, the Kang, the Crystal Mountain.

In the very language, in other words, the “I” is subsumed in all the great forces around it, and everything becomes a single breath, in which the I disappears. Better yet, none of the immemorial presences that swallow up the I are without their shadow sides (the “requiem birds,” the “black river,” the Crystal Mountain, which has just been described as a “castle of dread”) so that we never forget that one of Matthiessen’s main companions on the journey is Death. The sentence enacts the very fading of the I into the mountain.

As the book concludes, we have learned something about the nature (you could say the folly) of expectation and the beauty of the truth that all expectations often cover up. And what of the snow leopard he had hoped to see? We see the snow leopard’s prints, we feel its presence everywhere, but we realize that the sighting of the rare animal isn’t important at all (the author has, in some ways, sighted the rare animal, more germane to his purposes, that is himself). We note that teachers may come where you don’t look for them—in yellow-eyed men who seem to be demons—and that the temples that are full of wisdom in ancient lands are locked. We realize—and this, I think, is the most important point of The Snow Leopard, and begins to bring us back to Alex—how much every trip that really sustains us is in fact a journey home. The author, setting out, feels constantly the presence of some “inner garden” to which he’s lost the key; by the time he comes down, something has been put to rest—or clarified, if only for a moment—and the author has, perhaps, something to bring back to his boy that probably he could never have shared with him if he’d stayed home.

Most of all he—and surely we, too—have learned that there are no happy endings, or endings at all; everything is in constant movement, we can’t cling to any truth, and even the understandings that seemed so immortal near the Crystal Mountain are soon forgotten as “I trudge and pant and climb and slip and climb and gasp, dull as any brute” (every word a monosyllable again). Matthiessen appears to have learned nothing at all, as he descends, relieving himself on a dog who had attacked him a month before, failing to recognize a family he’s already met, still cursing at others, not only himself. The people around him “hawk and piss and spit” and as he wanders back through the seasons, from winter to autumn and then into summer, back into the world of clocks, he is greeted by “fresh frog mud” and “sweet chicken dung.”

And yet something has been registered, and the trip in search of the elusive animal that the author keeps just missing has taught us something that, for some readers at least, becomes a place, or a truth, they can never leave. And just before the end, at last, the story of Deborah Love’s death is fully told, and in the telling is accepted. In the hard-won days Matthiessen spent close to the Crystal Mountain, sitting still, the “sound of rivers comes and goes and falls and rises, like the wind itself.” And in the years since, readers and leaders and books have come and gone and fallen and risen, ceaselessly, and yet beneath all that, the mountain, the image of the leopard, the beauty of this tough-minded classic continue, quietly, to endure.

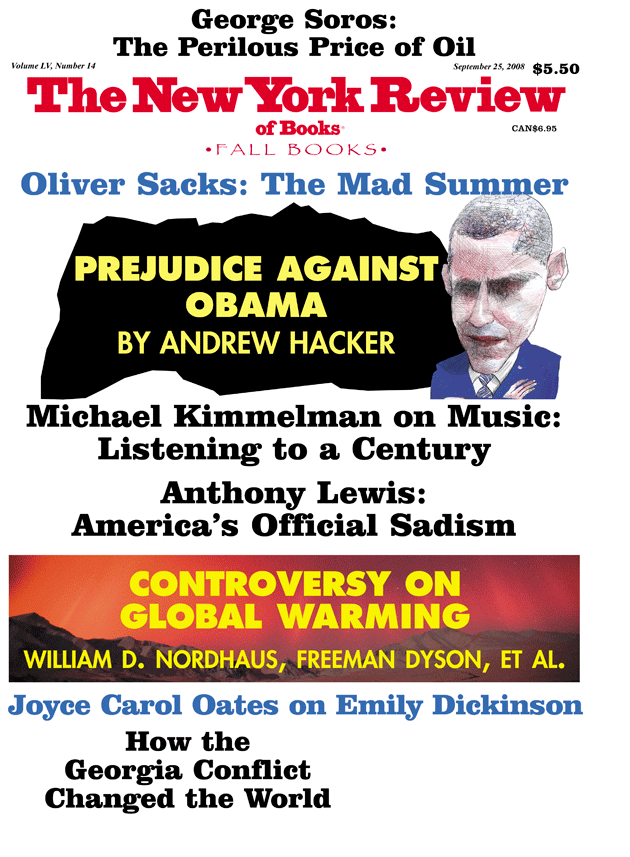

This Issue

September 25, 2008