When George W. Bush testified before the 9/11 Commission, Dick Cheney was with him in the Oval Office. What was said there remains a secret, but throughout the double session, it appears, Cheney deferred to Bush. Aides to the President afterward explained that the two men had to sit together for people to see how fully Bush was in control. A likelier motive was the obvious one: they had long exercised joint command but neither knew exactly how much the other knew, or what the other would say in response to particular questions. Bush also brought Cheney for the reason that a witness under oath before a congressional committee may bring along his lawyer. He could not risk an answer that his adviser might prefer to correct. Yet Bush would scarcely have changed the public understanding of their relationship had he sent in Cheney alone. “When you’re talking to Dick Cheney,” the President said in 2003, “you’re talking to me.”

The shallowest charge against Cheney is that he somehow inserted himself into the vice-presidency by heading the team that examined other candidates for the job. He used the position deviously, so the story goes, to sell himself to the susceptible younger Bush. The truth is both simpler and more strange. Since 1999, Cheney had been one of a group of political tutors of Bush, including Condoleezza Rice and Paul Wolfowitz; in this company, Bush found Cheney especially congenial—not least his way of asserting his influence without ever stealing a scene. Bush, too, resembled Cheney in preferring to let others speak, but he lacked the mind and patience for discussions: virtues that Cheney possessed in abundance.

As early as March 2000, Bush asked him whether he would consider taking the second slot. Cheney at first said no. Later, he agreed to serve as Bush’s inspector of the qualifications of others; his lieutenants were David Addington and his daughter Liz. Some way into that work, Bush asked Cheney again, and this time he said yes. The understanding was concluded before any of the lesser candidates were interviewed. It was perhaps the first public deception that they worked at together: a lie of omission—and a trespass against probity—to give an air of legitimacy to the search for a nominee. But their concurrence in the stratagem, and the way each saw the other hold to its terms, signaled an equality in manipulation as no formal contract could have done. It is hardly likely that an exchange of words was necessary.

The vice-presidential search in the spring of 2000 was characteristic of the co-presidency to come in one other way. It involved the collection of information for future use against political rivals. In this case, the rivals were the other potential VPs, among them Lamar Alexander, Chuck Hagel, and Frank Keating. They had been asked to submit exhaustive data concerning friends, enemies, sexual partners, psychological vicissitudes (noting all visits to therapists of any kind), personal embarrassments, and sources of possible slander, plus a complete medical history. Each also signed a notarized letter that gave Cheney the power to request records from doctors without further clearance.

All this information would prove useful in later years. Barton Gellman reveals in Angler that soon after Frank Keating was mentioned as a likely candidate for attorney general, a story appeared in Newsweek about an awkward secret in his past: an eccentric patron had paid for his children’s college education. No law had been broken, and nothing wrongly concealed; but the story killed a chance for Keating to be named attorney general; and the leak could only have come from one person. Doubtless most of the secrets in Cheney’s possession were the more effective for not being used.

Cheney by nature is a high functionary and inside operative, ready to learn and eager to ferret out the background of people and events, both the things he is supposed to know and the things he is not. It is symptomatic that in the Ford administration, when Cheney served as White House chief of staff, he declined a generous offer of cabinet status: higher visibility, he believed, would only diminish his actual potency. By the end of his time in that office, he had narrowed down access to the President to the people he himself preferred; and at his retirement, Cheney’s staff gave him, as Stuart Spencer recalls, “a bicycle wheel with all the spokes busted out except for one—his.”

A now forgotten aberration of the Republican convention in 1980 may have helped to crystalize his thinking about the advantages of a recessive stance. For a few frantic days that summer, it looked as if Ronald Reagan would need someone with demonstrable experience on the ticket if he was to have a chance in November; and there were serious discussions of a co-presidency to be shared between Reagan and Ford. Cheney, a close adviser to Ford, was an interested witness, and he saw how the excess and literalness of Ford’s “wish list” for vice-presidential powers caused the negotiations to break down. Still, this ended up a tantalizingly close call; and it could only have left Cheney thoughtful about future possibilities. Suppose one day the Republican Party nominated another charmer, cut out, like Reagan, for the getting of votes but as fundamentally uninterested as Reagan was in the actual running of government.

Advertisement

No two persons and indeed no twenty in Reagan’s administration enjoyed the power that Cheney settled into in 2001; but the role of the president in these two administrations has been much the same. He is the campaigner, the crowd-pleaser (if he can), the known presence at the visible desk who signs the laws and executive orders. The amiability of George W. Bush has turned out to be less versatile and translatable than Reagan’s: the boyish vulgar humor and back-slapping require easy success as a precondition; and apart from the three and a half years after the September 11 attacks—the period of the “fast wars” and the “war presidency”—his two terms in office have been marked by conspicuous failures.

Bush’s exceedingly low spirits have been palpable now for many months, and without the one to two hours of strenuous exercise that are the heart of his day, his mental state would surely be a good deal grimmer. And yet, for this very reason the growing evidence about Cheney’s bad judgments has not greatly diminished Bush’s reliance on him. If the vice-president dominates policy less than he did before 2006, the reason is only that others around Bush have become more confident. It remains nonetheless a relationship without any parallel in American history. “The vice president,” as Jacob Weisberg observes in The Bush Tragedy, “built his power over Bush by finding ways to give power to Bush.” There has never been a moment in this administration when the dependency let up.

Something subtly changed in Dick Cheney between 1995 and 2000, some equilibrium or inward balance of ambition and ordinary prudence. These were his years as CEO of Halliburton, where he did not post enormous profits: his decision, in 1998, to merge Halliburton with Dresser Industries and the subsequent asbestos claims against Dresser led the value of Halliburton stock to fall from $54 to $9 a share between August and December 2000.

Yet Cheney as CEO had a value as great as that of any official who has passed through the revolving door that separates government office from corporate chairmanships. His importance was as a connection maker, a facilitator, a speculative explorer of large innovations. While at Halliburton, Cheney would commission a study of the utility of employing private security contractors to fight in wars—only a piece of “research” at the time, but it would pay later for both the company and the vice-president, with the off-the-books contracts that by privatizing state protection kept much of the Iraq occupation out of public view.

These were the years, too, of Dick Cheney’s close association with the American Enterprise Institute and its offspring, the Project for the New American Century. The parent think tank, once an ordinary home for postwar business conservatism, had mutated, under the guidance of Irving Kristol, into the most lavish and energetic of the quasi-academic lobbies of neoconservative doctrine. The AEI, in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, had been transformed into an institute for the promotion of laissez-faire economics, militarized foreign policy, and the dismantling of the welfare state. It differed from, say, the Rand Corporation in eschewing any claim to impartiality of analysis. It was polemical and took confrontational positions that were disseminated early in the lectures and seminars open to resident fellows. The AEI differed, also, from an older centrist policy outfit like the Brookings Institution in having superior access to the mass media, thanks to careful self-advertisement and the coaching that its representatives often received from editors and agents such as Adam Bellow and Lynn Chu. A more-in-sorrow style was favored in discussing the grim necessity, for example, of increasing America’s nuclear stockpile or stopping the “culture of poverty” in the black community by cutting off federal programs.

Cheney’s familiarity with the policy institute way of talking was a steady and not a negligible factor in his ability to gain acceptance for his most outlandish maneuvers in the years between 2001 and 2003: the tax cuts and no-bid contracts with the Pentagon; withdrawal of the US from the ABM Treaty; the sudden commitment of the Pentagon to vast expenditures on missile defense, notwithstanding the record of test failures among missiles engendered by the Star Wars program under Reagan; the systematic exaggeration of the menace of Saddam Hussein in order to build support for a war against Iraq; and, in the triumphal mood of April 2003, the refusal to consider diplomatic contacts with Iran to obtain a “Grand Bargain” for peace in the Middle East.

Advertisement

Yet to those who knew the language, Cheney was only the forward edge of a policy long in the works, which had been announced almost in public in the turn-of-the-century strategy document Rebuilding America’s Defenses: the most substantial work commissioned by the Project for the New American Century. Like the authors of that treatise—among them Paul Wolfowitz, Lewis Libby, William Kristol, Frederick Kagan, and Stephen Cambone—and like the adepts of American hegemony at the AEI, Cheney, before he took office as vice-president, had concluded that there were no necessary limits on US domination of the world. This conviction hardened during the Clinton years—a window of time, as neoconservatives sometimes say, in which America could have asserted far more control than it did, and with a freer military hand. Cheney’s institutional prowess and his readiness to execute policies long in the making point to a larger pattern that James Mann wrote well about in Rise of the Vulcans.1

Republicans, since 1975, have had a foreign policy establishment that stays in place even when they are out of power. (The Democrats can claim nothing of the sort.) Through the continuity of neoconservative advisers, the military-statist wing of the Republican Party has thus, for three decades now, had the consistency and coherence of a shadow government. Though remarked by no one at the time, most of its essential policies—including “force projection” in the Middle East and continued pressure on Russia in spite of the fall of communism—were already in place by 1996, when the leading foreign policy adviser to Robert Dole was Paul Wolfowitz.

The Cheney doctrine of preventive war was first announced in a document called Defense Planning Guidance, drafted in 1992 by Zalmay Khalilzad—now US ambassador to the UN after serving as ambassador to Iraq—and revised by Lewis Libby. This guide was cleared for public release in early 1993 by Cheney in his final days as George H.W. Bush’s secretary of defense. Cheney took considerable pride in the prescription here that the US should “act against” emerging threats “before they are fully formed.” George W. Bush would still be echoing those phrases in his June 2002 commencement address at West Point: “We must take the battle to the enemy, disrupt his plans, and confront the worst threats before they emerge.” Richard Perle saying “We have no time to lose” (July 11, 2002) and Cheney himself telling the Veterans of Foreign Wars that “time is not on our side” (August 26, 2002) kept up the same drumbeat with the same theory to support them. Defense Planning Guidance conferred on America the right to launch at will an international war of aggression. As for the larger strategy, extractable from Rebuilding America’s Defenses, it was marked by an overriding ambition for global mastery, for the possession of irresistible military forces, for an expanded arsenal of nuclear weapons, and for large new investments in missile defense. These publications of 1993 and 2000 now seem a pair of symbolic brackets around the neoconservative exile that was the Clinton administration. All along, this was the normal thinking around the AEI and the Cheney circle. Yet when placed alongside the norms of the containment policy during the years 1946–1989, the new dogma betrayed a shift so tremendous that it could not have been ratified without a layer of well-instructed opinion makers to prepare and soften its acceptance.

Never before, in the history of the United States, has there been an ideological camp so fully formed and equipped to extend itself as neoconservatism in the year 1999. It was, and remains, a sect that has some of the properties of a party. There are mentors now in the generation of the fathers as well as the grandfathers, summer internships for young enthusiasts, semiofficial platforms of programmed reactions to breaking news. But to grasp their collective character, one must think of a party that does not run for office at election time. They can therefore evade responsibility for botched policies and the leaders who promote those policies. Donald Rumsfeld had his first and warmest partisans among the neoconservatives, but they were also the first, with the solitary apparent exception of Cheney, to identify him as a scapegoat for the Iraq war and to call for his firing when the insurgency tore the country apart in 2006.

With the peculiar tightness of its loyalties and the convenience of its immunities, neoconservatism in the United States now has something of the consistency of an alternative culture. Its success in penetrating the mainstream culture is evident in the pundit shows on most of the networks and cable TV, and in the columns of The Washington Post and The New York Times. In the years between 1983 and 1986, and again, more potently, in 2001–2006, the neoconservatives went far to dislocate the boundaries of respectable opinion in America. The idea that wars are to be avoided except in cases of self-defense suffered an eclipse from which it has not yet returned, largely owing to the persistence of respected opinion makers in urging the spread of freedom and markets by force of arms. More particularly, and to confine ourselves to recent events, the nomination of Samuel Alito and the drafting and legitimation of the “surge” strategy by Retired General Jack Keane and Frederick Kagan of the AEI could not have succeeded as they did without the early and organized advocacy of the neoconservative camp.

How did they get so close to Dick Cheney? The answer lies in the fact that Cheney has an inquisitive mind, but from the accidents of his career and placement, he was for a long time a thinker deprived of intellectual society. Neoconservatism, as it developed in the 1980s, came to have its own heroes (Robert Bork), its canon of revered texts (Allan Bloom’s Closing of the American Mind), and a set of prejudices delivered in a reasonable tone: hostile to individual liberty, appreciative of modern technology, friendly to religion as a guide to morals and an engine of state power. It was, to repeat, a substitute culture of satisfying density. The AEI along with journals like Commentary and, more recently, The Weekly Standard offer, for those who take the full course, a total environment, an idiom of managerial-intellectual judgment that blends the rapidity of journalism with the weightier pretensions of an academy.

In the Washington of the 1980s, the elder Kristols and the Cheneys were rising together, and they became close friends. This alliance easily passed to the younger generation: William Kristol in 2003 boasted to David Carr of the The New York Times (“White House Listens When Weekly Speaks”) that “Dick Cheney does send over someone to pick up 30 copies of [The Weekly Standard] every Monday”—a statement that remains the best clue we have to the number of persons who work for the vice-president. The self-confidence of this substitute culture fortified Cheney’s sense that he had always already heard the relevant views, and that he had come into contact with the best minds—minds free of the conformist cant and the cost-free sentimentality of modern liberalism.

Cheney’s ruling passion appears to be a love of presidential power. Go under the surface a little and this reveals itself as something more mysterious: a ceaseless desire of power after power. It is a quality of the will that seems accidentally tied to an office, a country, or a given system of political arrangements.

Jack Goldsmith, the head of the Office of Legal Council who fought hard against encroachments on the laws by Cheney and his assistant David Addington, remarked later with consternation and a shade of awe: “Cheney is not subtle, and he has never hidden the ball. The amazing thing is that he does what he says. Relentlessness is a quality I saw in him and Addington that I never saw before in my life.” Yet there is nothing particularly American about Cheney’s idea of government, just as there is nothing particularly constitutional about his view of the law; and no more broadly characterizing adjective, such as “Christian,” will cover his ideas of right and wrong.

Those who have studied him most closely—James Mann, Charlie Savage, Barton Gellman—agree that his drive to consolidate executive power goes back to one formative experience of seeing men of power checked and denied their prerogatives. As Gerald Ford’s chief of staff, he was a witness, close up, to the Church Committee investigations of the mid-1970s. The reforms that followed those investigations would open up rights for citizens against domestic surveillance, and would create the machinery for lawmakers to curb the exuberance and inspect the conduct of the national security apparatus. Among the reforms of the time was FISA—the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act—which Cheney deplored as soon as it passed and has sought ever since to circumvent. Here, as elsewhere, Addington may be supposed to give an uncensored glimpse of the vice-president’s view: “We’re one bomb away from getting rid of that obnoxious court.”

Something deep and unspoken in Cheney plainly rebels against the idea that conventional lawmakers, whose only power lies in their numbers, could ever check or by law prevent the actions of a leader vested with great power. He thought Nixon should not have resigned, and advised George H.W. Bush not to seek approval from Congress for the first Gulf War. Even at the time of the Church investigations, Cheney made an exception for the chief executive to the Freedom of Information Act, and secreted in a vault the government’s “family jewels”: findings of an internal investigation that he believed should be a state secret. These papers, declassified by the CIA in June 2007, included evidence of CIA kidnappings, assassination plots, and illegal domestic spying.

He sought and obtained the resignation of William Colby as director of the CIA for too readily cooperating with the Church Committee; but he could also count on some reliable friends in his rebellion. Brent Scowcroft, who wrongly took Cheney to be a moderate, concurred for pragmatic reasons of his own. A more wholehearted ally was a young lawyer from the Nixon justice department, Antonin Scalia. By 1977, one thing was clear alike to Cheney’s allies and his opponents. He wanted a great deal of power to be held as closely as possible by the president. When he ran for Congress in 1978, and won election for the first of five terms, he got himself quickly appointed to an odd combination of committees: Ethics and Intelligence. They had in common the access they offered to secrets of entirely different kinds.

One of Cheney’s first public statements as secretary of defense under George H.W. Bush was a talk at an AEI conference in May 1989, entitled “Congressional Overreaching in Foreign Policy.” There, already, he spoke of the “inviolable powers inherent in the presidential office.” On the other hand, he saw Congress as a body of “535 individual, separately elected politicians, each of whom seeks to claim credit and avoid blame.” A contempt for the readiness to compromise and the want of resoluteness in Congress as a whole marked Cheney’s utterances on the subject from the moment he left Congress.

But some such disdainful view of lawmakers had been implicit a year earlier, in the Iran-Contra Minority Report, which he released in the closing months of the Reagan administration. Secret operations in Nicaragua in the mid-1980s, undertaken by elements of the National Security Council and the State Department, seemed to Cheney justified by the legitimate powers of the unitary executive. Even though Congress had made a law expressly forbidding those actions, the fault lay with Congress for having meddled in affairs that belonged by right to the president. The US invasion of Panama in December 1989—overseen by Cheney as secretary of defense—was in this sense not only a rehearsal for the first Gulf War but a vindication of Reagan’s use of executive power south of the border.

Soon after becoming vice-president, Cheney plucked out of obscurity and brought back to government two men, John Poindexter and Elliott Abrams, still under a shadow from having been charged with various crimes in the Iran-contra prosecutions. Poindexter became the projector of Total Information Awareness—a War on Terror idea rejected by Congress, which would have encouraged Americans to spy on their neighbors—while Abrams was made an adviser on Middle East policy and then adviser for global democracy strategy. Poindexter would resign in 2003 over the scuttling of his fantastic proposal that the military run an on-line betting service to reward persons who correctly forecast future terrorist acts, coups, and assassinations. Abrams stayed with Middle East policy and in 2006 secured a declaration of American support for the Israeli bombing and invasion of Lebanon. A zeal that touched the brink of recklessness had always belonged to the public characters of both men.

Yet Cheney had been given carte blanche by George W. Bush to run the transition in 2000–2001: a solitary commander dispensing orders to an obedient crew. Bush was simply not part of this scene. Every member of the first Bush cabinet was approved by Bush, of course, but every one happened to have been Cheney’s first choice. (When Paul O’Neill, at Treasury, offered dissident comments on the economic program—including opposition to Bush’s tax cuts and Iraq war plans—Cheney thought he should go and Bush without any question agreed.) Yet his control went far deeper. In assessing this administration, one must never forget the advantage bestowed by interlocking circles of previously enjoyed patronage. Not only to Wolfowitz and Libby and Addington had Cheney been a patron—the maker of promotions, for them, long before Bush came on the scene—the same could be said for Robert Zoellik2 and, closest of all to the President, his chief of staff Andrew Card.

Meanwhile, to monitor the policymaking at State he had John Bolton and Robert Joseph, while, at Defense, there were Stephen Cambone, Douglas Feith, and later Eric Edelman. Higher up was Rumsfeld: a former superior who became an equal and then—because he was less artful and made himself obnoxious to others as Cheney did not—a subordinate with privileges. Last and easiest to forget, there was Colin Powell: the lately promoted four-star general whom Cheney, in an unprecedented move in 1989, had brought in over the heads of the Pentagon and created as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Such favors are never forgotten; and Powell’s old debt to Cheney, as much as Cheney’s undermining of departmental dissent in the runup to the war in Iraq, would have inhibited Powell from the honest scrutiny of the plan for war that many expected from a conscientious man in his position.

How far did Cheney’s interests and involvement go into the making of policy? He has conceded that he was allowed by his understanding with Bush to participate on some issues and keep an enforced silence on others. From what Jane Mayer and Barton Gellman report, this appears to have been an understatement of his range. According to Gellman, all things military were Cheney’s province; also domestic and foreign policy; natural resources and energy policy; and nominations and appointments. The burden of Jane Mayer’s book is that the President allowed Cheney—armed with an emergency exception worked up by Addington, Yoo, and others—to transgress the limits on state action toward American citizens as well as enemy prisoners and unknown persons taken in combat. Bush wanted this job done; but Cheney was the master architect, managing at once the details and the rationale—and Bush signed off. Bush approved, that is, extreme interrogations that included the drowning torture; renditions to “black sites” where prisoners are tortured by the police of states known for their brutality; and the creation of a class of stateless persons-without-rights, “enemy combatants,” to reside at Guantánamo without protection from American laws or any other laws. The meaning of the Office of the Vice President was that actions were to be meditated and ordered there; in the President’s office, they were ratified as accomplished facts, and given the force of law.

Cheney’s team did not take no for an answer. The vice-president early on impressed Bush with the maxim that negotiation is a form of surrender, and Bush was happy to echo the sentiment: “We’re not going to negotiate with ourselves on taxes.” But Addington said it straighter: “We’re going to push and push and push until some larger force makes us stop.” They were seldom met by that force—in the President or the people around him, or among the Democrats in Congress. If anything, the President, by his incidental exhibitions of will, troubled the designs of the Office of the Vice President more than the opposition party. Ahmad Chalabi, for example, was a favorite client of the Cheney circle, and their choice to lead an Iraqi puppet state after the war. He was a fluent and gifted confidence man; but he got on Bush’s nerves. “What was Chalabi doing sitting behind Laura last night?” he asked after the 2004 State of the Union. The mass protests led by the Ayatollah Sistani and Bush’s irritation at Chalabi combined to turn the administration from the idea of a patriot-dictator to the plan for a constitutional assembly in Iraq.

And they have never been stopped for long. The story of the National Security Agency data mining in violation of FISA has a typical shape in this regard. The White House successfully frightened The New York Times out of publishing the discovery of this practice for a year after James Risen’s story was ready to go. When it did appear, the attorney general, Alberto Gonzales, threatened to prosecute the newspaper. Meanwhile, the head of the NSA, Michael Hayden, took shelter in a jesuitical economy of truth, saying that one end of an intercepted “conversation” had to be in a foreign country before a wiretap would cover an American. This was true of phone conversations, but not of the transactional data of phone calls and the numbers, the addresses and subject lines of e-mails, and so on.

“Government,” writes Gellman, “collected information on a scale that potentially touched every American”; and presumably it still does, since in June 2008 Congress handed the President a nerveless compromise allowing minimal oversight of the renewable sweeps of electronic communications. The structure of the intelligence agencies and departments since that scandal has brought them even closer to Cheney. The cooperative attitude of Hayden at the NSA got him a job as head of the CIA; and the new position of director of national intelligence was shifted from John Negroponte to someone more nearly a protégé: Michael McConnell, a subordinate of Cheney’s at Defense in the administration of George H.W. Bush.

About none of these actions has Cheney ever been called, by a subpoena from Congress or an urgent demand from the press, to answer questions regarding the extent and legality of his innovations. It is as if people do not think of asking him. Why not? The reluctance shows a tremendous failure of nerve, from the point of view of democracy and public life. But there is a logic to the sense of futility that inhibits so many citizens who have been turned into spectators. It comes from the dynamic of the co-presidency itself, to which the press has grown acclimatized. Bush is the front man, and is known as such. He takes questions. If he answers them badly, still he is there for us to see. To address Cheney separately would be to challenge the supremacy of the President—a breach of etiquette that itself supposes a lack of the evidence that would justify the challenge.

The fact that Bush’s answers are so inadequate, from a defect of mental sharpness and retentiveness as well as dissimulation, kills the appetite for further questions. But the fact that the questions have, in a formal sense, been asked and answered lets the vice- president off the hook. Thus the completeness of his silence and seclusion, for long intervals ever since September 11, 2001, is an aberration that has never been rebuked and has often gone unnoticed. “There is a cloud over the vice-president,” said the prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald in his summation at the trial of Lewis Libby. “That cloud is something you just can’t pretend isn’t there.”

But for much of the second term of the Bush-Cheney administration, we have been pretending. The man who held decisive authority in the White House during the Bush years has so far remained unaccountable for the aggrandizement and abuse of executive power; for the imposition of repressive laws whose contents were barely known by the legislature that passed them; for the instigation of domestic spying without disclosure or oversight; for the dissemination of false evidence to take the country into war; for the design and conduct of what the constitutional framers would have called an imperium in imperio, a government within the government.

—October 22, 2008

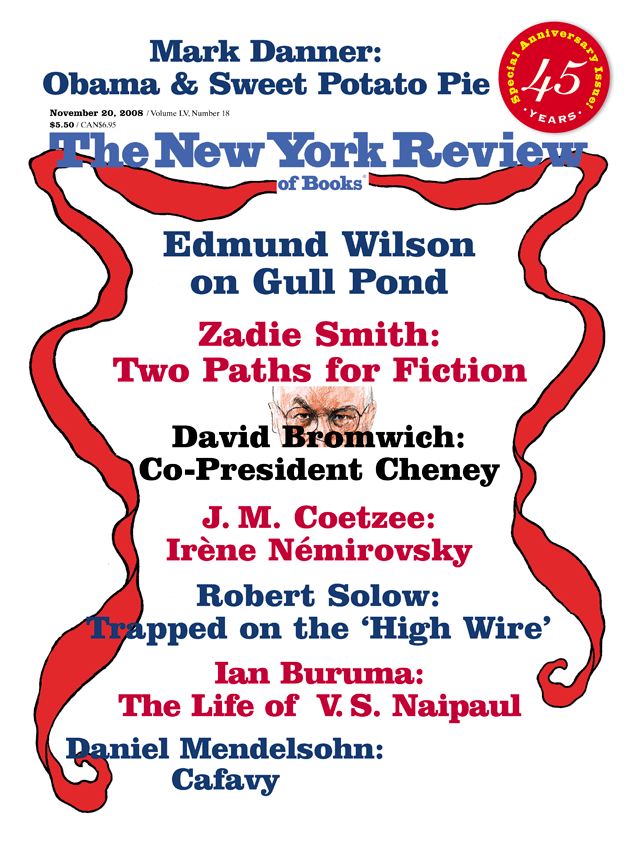

This Issue

November 20, 2008

At Gull Pond

Two Paths for the Novel

-

1

Viking, 2004; reviewed in these pages by Arthur Schlesinger Jr., September 23, 2004. ↩

-

2

Now president of the World Bank, he was deputy secretary of state in 2005 and 2006, and US trade representative from 2001 to 2005. ↩