Ever since the great historian Fernand Braudel consigned isolated human events to l’histoire événementielle, calling them mere “surface disturbances, crests of foam that the tides of history carry on their strong backs,” it has been harder to write of decisive moments in world history. The ineluctable undercurrents of geography and trade, the impact of technologies and climate, conspire to dwarf significant human events. In the face of these groundswells, at the most extreme, battles and treaties and the deeds of “great men” wither into transience.

For the Mediterranean, of course, the flagship of the new history was Braudel’s monumental The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Its legacy is still pervasive. Yet Braudel himself indicated its limitations, and for others the notion of historical turning points has proved irresistible: especially, of late, the watershed between expansionist Islam and European Christianity. This crucial event has been assigned inter alia to the Battle of Tours in 732, where the Frankish leader Charles Martel turned back the Moorish army flooding across France, and variously to the siege and the Battle of Vienna (in 1529 and 1683), which checked the Ottoman advance into Eastern Europe.

In Empires of the Sea: The Siege of Malta, the Battle of Lepanto, and the Contest for the Center of the World, Roger Crowley describes another such civilizational crisis: this one between 1565 and 1571, when the Ottoman Turks pushed westward across the Mediterranean. Their empire was then at its height. They had absorbed Egypt and almost the whole North African littoral; to the east they were battering on Persia, to the north threatening Vienna. Over the Mediterranean itself—ancient Rome’s “center of the world”—the imperial Turkish navies and their corsair auxiliaries were spreading terror down the coasts of Italy and even Spain. But lying strategically across their path, in a pendant below Sicily, was the tiny island of Malta. From here the Knights of St. John, soldier-monks dedicated to recovering the Holy Land, harassed Muslim shipping and even pilgrimage.

Malta’s survival of the great Ottoman siege in 1565 was to become one of the redemptive epics of Christendom. And a greater one was to follow. In 1571 the western Mediterranean powers—Spain, Venice, the Papacy—united at last in fear, put an end to Turkish maritime expansion at the horrifying Battle of Lepanto.

These titanic events, and those preceding them—the Ottoman capture of Rhodes in 1522, the battles for North African ports, the corsair raids on Europe—are the rich meat of Crowley’s book. Empires of the Sea, confessedly, is less a scholarly or innovative study than a work of passionate and informed enthusiasm, much reliant on the formidable histories and compendia of Braudel, Kenneth Setton, Stephen Spiteri, and others. Crowley’s work belongs with a (very British) tradition of suspenseful military history, eschewing primary research for a wide canvas. Indeed the state archives of Madrid alone (Philip II reigned for forty-two years and could reputedly generate 1,200 missives a month), let alone those of the Vatican, Istanbul, and Venice, form a humbling labyrinth.

Instead, the merits of Crowley’s book are those of narrative skill and balanced empathies. The changing pageant of tactics and weaponry, the pendulum of power and morale, make for compulsive reading. Within the strictures of published material, the author (who has lived in Istanbul) charts the Muslims’ anger and misgivings alongside the Christians’—together with their mutual demonizing—and his portrayal of the principal protagonists emphasizes how sheer force (or feebleness) of personality could crucially alter events. Only occasionally the repetition of bloodshed grows wearisome, and it is a relief when the narrative withdraws to the quieter checkerboard of politics, where the King of Spain prevaricates in the Escorial or the Sultan urges action from his kiosks above the Golden Horn.

Many of these leaders were remarkably old, far older than their counterparts would be today. At the siege of Malta the Turkish commander Mustafa Pasha was seventy, as was the hoary Sultan Suleiman manipulating him from Istanbul. Mustafa’s Christian counterpart, the Grand Master Jean de La Valette, a veteran of the siege of Rhodes forty-three years before, was fighting on the ramparts at the age of seventy-one, while the corsair leader Dragut died there in action at the age of eighty.

Crowley nicely sketches in the brooding figures who engineered these bloody dramas: the fanatic Pope Pius V; the grimly reclusive Philip II (who seems to have been born old); above all the great Suleiman the Magnificent (as the West dubbed him), darkening into a pious asceticism just as his enemy Philip was immuring himself almost two thousand miles to the west:

Advertisement

Where the early years had seen extravagant shows of worldly splendor in competition with the potentates of Europe, Suleiman’s reign became marked by increasing piety and sobriety, as he sought to emphasize his position as guardian of the caliphate and leader of Orthodox Islam. An austere gloom fell on the court. Hurrem [his wife] died and Suleiman retreated from the world. He was rarely seen in public and watched meetings of the divan—the council of state—silently from behind a grille. He drank only water and ate off clay plates. He smashed his musical instruments, forbade the sale of alcohol, and gave his energy to the building of mosques and char-itable foundations. He was crip- pled by gout, and rumors of his failing health circulated across Europe.

This somber recluse was far removed from the brilliant young man who had driven the Knights of St. John from Rhodes in 1522. But it was against the same enemy, now reduced to the island of Malta, that the aging sultan launched the penultimate campaign of his reign. In March 1565, in what Crowley judges “the most ambitious maritime venture in the Mediterranean since the early Crusades,” there departed from Istanbul an armada that would soon burgeon into 130 galleys with hundreds of auxiliary craft carrying 30,000 men—including six thousand elite janissaries—and sixty-two land cannons with two boulder-hurling basilisks and two thousand tons of gunpowder. Within a few months the centralized Ottoman administration had assembled a mobile and self-sustaining armament to survive in enemy territory a thousand miles away, down even to its prefabricated wooden palisades. The fleet’s destination still remained secret after it had set sail; but already Turkish engineers, disguised as fishermen, had slipped into Malta’s harbor and measured its fortifications with their fishing rods, bringing back accurate estimates.

Despite all this, the Turks were uneasy. The fleet’s supply line was dangerously attenuated. Malta itself was barren of timber for siegeworks, and its limestone resistant to undermining operations. Its populace, aside from the intransigent knights, was deeply hostile to the Ottomans. Moreover the magnificent Turkish fleet had in fact been assembled in haste, its numbers made up even by pardoned criminals. Its overall commander, Mustafa Pasha, a cruel and temperamental veteran of land campaigns, was united with its naval commander only in jealousy of its third leader, the corsair Dragut. Above all, the sailing season for galleys—six months, perhaps—left a limited window for success.

But in Malta, as the giant fleet advanced with a swiftness that astonished contemporaries, the knights’ situation looked hopeless. Their ramparts were both outdated and incomplete. They could muster barely five hundred heavily armed knights, with three thousand Maltese militia in padded jerkins and roughcast helmets. To these Philip II, the knights’ nominal suzerain, added some companies of Spanish and Italian professional soldiers, before the seaways closed against them.

Malta today has the finest fortified harbor in the world, and even in 1565 this four-mile inlet, spiked with sudden headlands, formed a complex maritime citadel. High above the harbor mouth stood the castle of Saint Elmo, and sheltering beyond it the fortified promontaries of Birgu and Senglea enclosed the knights’ modest town and the inlet where their fleet stood at anchor.

The small, star-shaped fort of Saint Elmo was the strategic key. It was garrisoned by some 750 men, mostly seasoned Spanish soldiers. But from the west and south it was fatally vulnerable, and the Ottoman siegecraft—ballistics, mining, earthworks—was unequaled in its time. Surrounded on three sides by the Turkish artillery, the fort was pounded to dust over four weeks. At first it could be reinforced by boats from the headlands of Birgu and Senglea a few hundred yards across the harbor. Then this passage too became a death trap, and the knights at Birgu could only watch in dismay as day and night the fort across the water was shaken by cannon and lit by incendiary flashes.

The defense of Saint Elmo became the penultimate romance of Crusader Christendom. It continued even after the moats had been leveled with brushwood and the captured outworks raised above the inner fort, so that cannons and snipers riddled the whole defense. The fort’s commander, badly wounded, was hauled into a chair on the ramparts, where he remained, sword in hand. Attack after attack foundered before the dwindling defenders:

All night Ottoman guns pummeled the shattered walls; regular false alarms kept the weary men blinking out into the darkness. Now they could go only on all fours beneath the parapet; it was impossible to leave their posts. The priests crawled up to them with the sacraments.

By the time the fort was taken and its last defenders annihilated, the knights on Birgu, under their Grand Master La Valette, had gained precious time to bolster their landward defenses.

Advertisement

Now all Europe was ringing with alarm. Prayers were said even in Protestant England, and a feverish Pope Pius IV, aware that Rome was the ultimate Turkish goal, declared that he would die before fleeing the Vatican. Meanwhile on Malta, as at Constantinople over a century before, the Ottomans dragged ships overland on greased rollers to attack from an unexpected quarter. But at night Maltese divers drove into the seabed a palisade of underwater stakes to thwart the ships before they reached the seawalls, and the Turks were repulsed with the loss of four thousand men.

The Ottomans now took to wearing down the defenders by abruptly shifting the focus of assault, inflicting sudden night bombardments and relentlessly tunneling to lay explosives. The landward bulwarks were reduced to rubble. The Ottoman commander Mustafa Pasha, himself a veteran of Rhodes, urged on his men in person and was twice wounded. By late August, as heavy rains doused the defenders’ arquebuses and grenades, the Turks advanced from their waterlogged trenches and breached the city. The two septuagenarian commanders, Mustafa and La Valette, almost met in the rubble. Then the rain stopped, the knights rallied, and the town survived. A few days later a long-delayed Christian relief force landed unopposed from Sicily, and the Ottomans, after a last disastrous battle, sailed away in disorder, leaving half their army dead behind them.

One of the most striking aspects of this conflict—and of the whole period—was the instability of the Christian–Muslim divide. If this was a clash of civilizations, it was a complex and (in a sense) artificial one. The Ottoman Empire, in particular, was both ethnically and religiously heterogeneous. The sultans themselves, who were born within harems of foreign women (the Christian Georgians and Circassians were favorites), had scarcely a drop of Turkish blood. More potently, the upper echelons of the Ottoman civil service were typically composed of men captured as Christian children, converted to Islam, and brought up in exclusive loyalty to the sultan. Likewise the elite janissaries (although Crowley never mentions this) were not Turkish-born but captured in infancy.

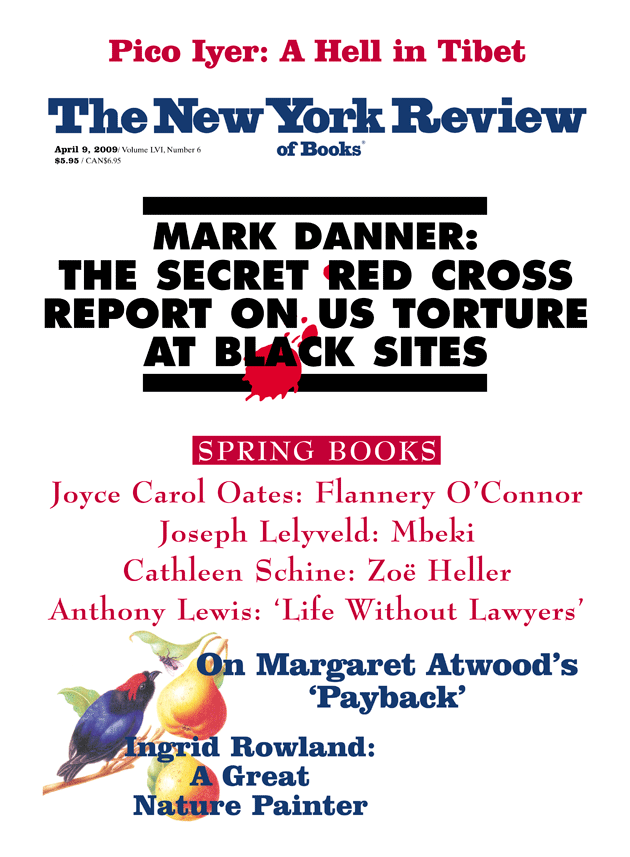

National Maritime Museum, London

Matteo Perez d’Aleccio: The Siege of Malta: Siege and Bombardment of Saint Elmo, late sixteenth century. Roger Crowley describes this painting in Empires of the Sea: ‘On May 27, 1565, the Ottoman army converges on Saint Elmo. White turbans swarm up the Sciberras Peninsula; to the right, miners and siege engineers lug up materials and tools; to the left, shrouded corpses are carried off to their tents; center foreground, the pashas discuss tactics, flanked by janissaries with arquebuses.’

The Habsburg ambassador to the Sublime Porte, Augier Ghislain de Busbecq, wrote with admiration of this Oriental hierarchy, so different from the dynastic courts in the West. The Turks gave to breeding the care which in Europe was reserved for horses and hawks, he remarked, and at an audience with the sultan

there was not in all that great assembly a single man who owed his position to aught save his valor and his merit…. Those who receive the highest offices from the sultan are for the most part the sons of shepherds or herdsmen, and so far from being ashamed of their parentage, they actually glory in it….

The less systematic absorption or enslavement of Christians had curious and unsettling effects. On the fringes of the Ottomans’ power their corsair allies were often renegade Christians, exiled or captured, and converted at least formally to Islam. (“They lived and died by the sea and gave their ships beautiful names….”) The Ottoman commander Kara Hodja, who blockaded Venice in July 1571, was a defrocked Italian friar. The foremost Barbary corsairs, the Barbarossa (“Red Beard”) brothers, were by birth half Christian. Yet their galleys were rowed by hundreds of Christian slaves, and they terrorized, in particular, the southern coasts of Italy. Crowley writes:

Europe was on the receiving end of the slavery it was starting to inflict on West Africa—though the numbers slaved to Islam far exceeded the black slaves taken in the sixteenth century…. The corsairs entered Italian folklore as agents of hell, and what made it more difficult to bear was that as often as not Satan’s emissaries were renegade Christians who had defected to Islam through circumstance or choice, and who were extremely well placed to maximize damage on their native lands.

The Ottoman army that disembarked on Malta was sprinkled with such apostates—converted Spaniards, Greeks, and Italians—and even Christian mercenaries. Defectors plagued both sides, for the knights’ forces, too, contained risky elements: Muslim converts and slaves. Both Turkish and Christian war councils were routinely betrayed. The Ottoman plan to transport ships overland was given away by a fifty-five-year-old Greek who had been captured and converted to Islam in childhood. “His heart touched by the Holy Spirit” (wrote pious chroniclers), he swam across the harbor to the Christian shore. Soon afterward, from the other side, a Spanish soldier, a converted Muslim, was “prompted by the Islamic banners still fluttering on the shoreline to return to the faith of his fathers,” and carried back (fatally inaccurate) intelligence to the Ottomans.

The psychology of these defectors defies easy patterning. Their motives seem to range from cowardice, greed for reward, or escape from slavery to the more shadowy regions of ethno- religious guilt and nostalgia. Sometimes during the siege the opposing trenches drew so close that Christian renegades shouted coded support to their old co-religionists. Once, wrote an Italian soldier, a janissary emerged from the trenches to present his enemies with “some pomegranates and a cucumber in a handkerchief, and our men gave back in exchange three loaves and a cheese.”

But more generally the battle—and the era—was notable for its cruelty. After the fall of Saint Elmo the mutilated corpses of its defenders were nailed to crosses in parody of the Crucifixion and launched across the harbor to horrify their brethren in Birgu. The Christians’ response was to execute all their Turkish prisoners and catapult their heads back across the straits.

Compared to the unified Ottoman war effort in 1565, the Christian mobilization had been slow and disordered. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453, when only the Genoese came to the city’s rescue, remained an unlearned lesson. Through much of the sixteenth century Christian Europe was split by hostility between the Spanish Habs-burgs and the French Valois. In 1536 Sultan Suleiman and the French King Francis I even signed a treaty with the unspoken aim of weakening Spain; and in 1543–1544, to the scandal of Christendom, the predatory fleet of Hayrettin Barbarossa was being revictualed in the harbor of Toulon. Only in 1566, under the belligerent new pope, Pius V, did a fresh Holy League assemble, and in 1571 it was still falteringly in place as its fleet sailed to meet “the Turk” at Lepanto.

The Battle of Lepanto is the second set piece of Crowley’s book. Played out on the sea in open galleys—the last such major battle in history—it conveys a feeling of profound anachronism; yet it set the Christian–Muslim division in the Mediterranean far into the early modern age. The Holy League fleet was born of a shaky alliance between Spain, Venice, the Papacy, and the Knights of St. John. The Muslim armada, marginally the bigger, was composed of the imperial Ottoman navy and its Algerian corsair allies.

Yet the Ottomans were uneasy on the sea. Seaborne trade was largely the province of their Christian and Arab subjects, and their navy was employed above all in amphibious siege and the transport of armies. But now, in the autumn of 1571, with the great Suleiman long dead on a campaign in Hungary, his feeble and vainglorious successor Selim II ordered the fleet into headlong battle. Both forces, on faulty intelligence, had underestimated the enemy. Now, as they converged near the Gulf of Corinth off western Greece, each fleet watched with alarm as the opposing one expanded over the horizon, until 140,000 soldiers, mariners, and oarsmen were insensibly closing on one another in six hundred ships.

The day was decided by the superior firepower of the Christian fleet. Three or five cannons were mounted at the prow of each galley—a heavier armament than the Turks’—and six hybrid Venetian galleasses, built up like artillery platforms, were towed to the forefront of the Christian line and broke up the Ottoman advance with broadsides before the main fleets had engaged. Once enmeshed, the ships’ decks became the arena for a floating land battle. Here the advantage lay with the heavy Spanish musket, which, unlike the quick-firing Turkish bow, could discharge a shot that penetrated thick armor and even ships’ wood.

Lepanto occupies a curious military fault line between ancient and modern. It was fought with galleys almost identical to those that had clashed in this same gulf sixteen centuries before, when the ships of Antony and Cleopatra succumbed to those of Octavian at the Battle of Actium. There had, of course, been refinements to the galley (different rowing systems, outriggers, stern rudders) but basically these were still the sleek ships that depended on an endless supply of oarsmen, many enslaved. Now they were sailing into the age of gunpowder.

Besides the cumbersome but lethal arquebus, an array of incendiary weapons was wielded by both sides in this period—arms still in their infancy and dangerous to handle, but increasingly deadly. At the siege of Malta the contestants deployed chain-shot and hand grenades, primitive flamethrowers and brass firebombs exploding naphtha. Yet these coincided with the composite Turkish bow, the traditional weapon of a mounted nomad, and even with medieval crossbows, pulled out of armories when rain made the bow and musket ineffectual.

In time the manufacture of iron cannon—far cheaper than brass—would arm the steep-sided galleon, even the merchantman, to such advantage that the galley would disappear. But meanwhile the carnage of Lepanto left 40,000 men dead within four hours—a rate of slaughter, writes Crowley, unsurpassed until the battlefields of Flanders in World War I. The sea was so awash with corpses and debris that the surviving galleys could barely extract themselves. Almost a hundred ships had been destroyed, 137 Turkish galleys captured, and 12,000 Christian oarsmen freed; and such was Christian mercilessness that few of the enemy were taken alive.

Lepanto has been thought a turning point in Mediterranean history. Certainly no such battle was ever fought again. But modern scholarship inclines to reject such a conclusion. After the burst of Christian euphoria had subsided, it was not apparent that any profound strategic change had taken place. Within a year the Ottoman fleet had been rebuilt, and the Holy League was falling apart. Venice concluded an unfavorable peace with the Turks, and in 1580 Spain followed suit. The old Muslim–Christian division of the Mediterranean congealed, and would change little for another two centuries.

It is easy now to regard these borders as natural, and Lepanto a non sequitur. But Braudel himself suggests that this underestimates the profound psychological and material impact of the victory on a Christendom so long overawed by the Turks. To the Ottomans the loss of skilled manpower was perhaps more important than the loss of ships, which were replaced (albeit poorly) within a year. Lepanto may not have signaled a Christian resurgence, but it put a virtual end to Ottoman expansion westward.

It had been a terrible risk. Had the Holy League lost, Venice would have been fearfully exposed, and with it the heart of Italy, perhaps Rome itself. But after Lepanto, Crowley writes:

The competitors turned their backs on each other, the Ottomans to fight the Persians and confront the challenge of Hungary and the Danube once more, Philip to take up the contest in the Atlantic…. In the years after 1580, Islam and Christendom disengaged in the Mediterranean, one gradually to introvert, the other to explore.

On a still wider scale, of course, the weight of the world’s power, as in some seismic shift, was moving toward the countries of the Atlantic seaboard, and at last to the Protestant nations of the oceangoing north. To the east, the great artery of the Silk Road across Asia had been fragmenting for over a century, leaving the Ottoman Empire to stagnate at the dead end of the Mediterranean. Now and again Turkish galleys tried to attack Portuguese merchantmen in the Indian Ocean, but the day of the galley was over. “It is indeed a strange fact and a sad affair,” wrote an Ottoman mapmaker in the 1580s, that the way to the Indies had been paved by “a group of unclean unbelievers” instead of by his own people.

Such matters, however, are not the heart of Crowley’s book. He concentrates, rather, on the peculiar drama of sixteenth-century warfare itself, and leaves the reader less with the wider tides of diplomacy than with vivid images of human (and inhuman) events: with the Spanish soldier who wraps the stump of his severed arm in a dead chicken before returning to fight; with the pet marmoset of Don Juan of Austria, the Christian commander at Lepanto, breaking off arrows from the ship’s mast with its teeth; with the Christian and Turkish crews awash on a corpse-filled sea, their ammunition spent, pelting one another with oranges and lemons, insanely laughing. The impoverished young Miguel de Cervantes, whose left hand was maimed in the battle, later had his Don Quixote declare that after Lepanto “all the world learned how mistaken it had been in believing that the Turks were invincible at sea.”

This Issue

April 9, 2009