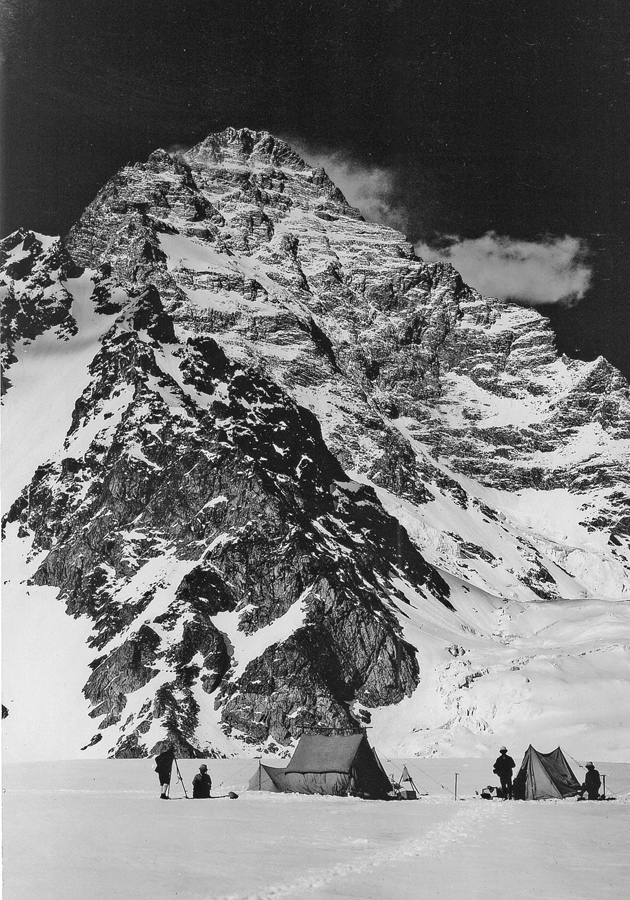

Fondazione Sella, Biella, Italy

‘The grandest of the early Himalayan expeditions, and also the least eccentric’: the camp of Luigi Amadeo, Duke of the Abruzzi, and his team below the west face of K2, 1909; photograph by Vittorio Sella, ‘one of the greatest of all mountain photographers,’ from Maurice Isserman and Stewart Weaver’s Fallen Giants

Maurice Isserman and Stewart Weaver’s authoritative history of Himalayan mountaineering, Fallen Giants, starts right at the beginning, 45 million years ago, with the collision of tectonic plates that threw up what the authors call “the greatest geophysical feature of the earth.” The Andes are the longest of the planet’s mountain chains, but the Himalaya and its adjacent ranges, the Karakoram and the Hindu Kush, are far higher. They contain all fourteen of the world’s peaks over eight thousand meters, or 26,247 feet; their northern rampart averages 19,685 feet—some five thousand feet higher than the Andes—and they are still growing: “To this day India plows into Tibet at the breakneck speed of five centimeters a year and lifts the Himalaya by as much as a centimeter.”

That little detail is characteristic of the book. Both authors are enthusiastic mountaineers who climb regularly in the United States and have gone trekking in the Himalaya, but they climb for pleasure, not for a living. Away from the hills, they are historians—Isserman has written extensively about American communism and the New Left; Weaver’s field is British imperial history and English liberalism—and they bring their professional skills and discipline to the subject in the form of meticulous research and a painstaking attention to detail. Fallen Giants is a big book in every sense—nearly 460 pages of text, eighty-five pages of notes, and a twenty-five-page bibliography—and the authors’ political take on the subject makes it unlike most other mountain histories.

Political historians do not usually bother with a subject as apolitical and seemingly frivolous as climbing, although mountaineering books are now accumulating as relentlessly as the Himalaya itself. A mere half-century ago, mountain climbing was still a minority pastime for an eccentric few who took pleasure in doing things the hard way, in steep places and bad weather, and were willing to risk injuring themselves in the process. Since risk and the adrenalin high that went with it were an essential part of its appeal, climbing was regarded as a questionable, slightly antisocial activity. As a result, climbers wrote about where they had been and what they had done, but they wrote mostly for other climbers and a relatively limited audience of armchair adventurers who preferred to be thrilled, or to suffer, by proxy.

Not anymore. In the years since 1953, when Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay first reached the summit of Everest, mountaineering, rock climbing, and mountain tourism—aka trekking—have been transformed into a mainstream leisure activity, indulged in by millions. Books about it figure in the best-seller lists and its needs are serviced by a thriving industry with an annual global turnover reckoned in billions: travel agents, commercial guiding outfits, and specialist manufacturers of everything from outdoor clothing, rucksacks, and tents to ice axes and arcane gear such as camming devices and offset nuts.

The Victorians were responsible for turning the Alps into what Leslie Stephens called “the playground of Europe,” but it was an exclusive playground for a limited few. One hundred and fifty years later, the Himalaya is in danger of becoming the playground of the developed world. As of August 1, 2008, 2,090 people have stood on the top of Everest. Both the South Col route that took John Hunt’s 1953 expedition six weeks to pioneer and the North Col route on which George Leigh Mallory and Andrew Irvine died in 1924 have been climbed from base camp to summit, solo and without oxygen, in less than seventeen hours. The mountain has also been climbed by a blind man, a teenager, and a sixty-four- year-old; it has been descended by skiers and snowboarders, floated down by paragliders, and flown over by balloonists. The problem with Everest is no longer how to get up it but how to dispose of the junk—the hundreds of used oxygen cylinders and tons of human excrement and waste food—that litters its flanks. In his official history of Everest, George Band, who was the youngest member of the 1953 expedition, calls it “the world’s highest garbage dump.”

Before the Victorians reinvented them as a form of recreation, mountains were of interest only to those unfortunate enough to live in them. In the Himalaya, they were holy places, a perpetual reminder of the gods—the Tibetan name for Everest is Chomolungma, “Goddess Mother of the World”—and their summits were forbidden to mere mortals. In Europe, superstitious Alpine peasants believed mountaintops were the abodes of witches, devils, and dragons. Lowlanders and people of sense chose to ignore the peaks, dismissing them as mere inconveniences—“considerable protuberances,” Dr. Johnson called them—put there to make life difficult for the civilized traveler.

Advertisement

According to Isserman and Weaver, the general change in European attitudes toward mountains began around the middle of the eighteenth century with the Gothic revival, the cult of the picturesque, and Edmund Burke’s

aesthetic distinction between the Beautiful—the regular, the proportioned, the visually predictable—and the Sublime—the dramatic, the unexpected, the awe inspiring—[which] thus provided…a ready vocabulary for the novel experience of mountain wonder.

For aesthetes, appreciating the beauty of the Alps was altogether different from climbing them. When John Ruskin was invited to lecture to the Alpine Club in 1865, seven years after its foundation, he used the occasion to denounce its members as Philistines:

You have despised nature [and] all the deep and sacred sensations of natural scenery…. The French revolutionists made stables of the cathedrals of France; you have made racecourses of the cathedrals of the earth…. The Alps themselves, which your own poets used to love so reverently, you look upon as soaped poles in bear gardens, which you set yourselves to climb and slide down again, with “shrieks of delight.”

Isserman and Weaver, being finely tuned to social distinctions and crushing British snobbery, interpret Ruskin’s diatribe as a matter of class warfare. “His remark dripped with class condescension,” they say. I wonder. Ruskin had a talent for vituperation, but his venom on this occasion had nothing to do with “class condescension” for the simple reason that, socially, there was no difference between him and his audience. The members of the Alpine Club were professional men—scientists, doctors, clergymen, lawyers, soldiers, even a few writers—gentlemen who could afford to travel to the Alps and stay there for as long they pleased, just like Ruskin himself.

There were differences between them, of course, but temperament aside, they were differences of nurture, not nature. Ruskin had been privately educated at home by tutors, whereas most of the founding members of the Alpine Club had suffered the rigors of a boarding school education designed to train the right kind of men to administer the British Empire. A taste for strenuous exercise, adventure, and deprivation had been beaten into them along with Greek and Latin, and mountaineering was a perfect way of satisfying it. “The authentic Englishman,” Leslie Stephen wrote cheerfully, “is one whose delight is to wander all day among rocks and snow; and to come as near breaking his neck as his conscience will allow.” For Ruskin, art critic and lover of mountain landscapes, such frivolity was barbaric.

Snobbery, of course, figured large in “the intensely status-conscious eyes of the Raj,” far larger, in fact, than the mountains themselves, especially in the first half of the nineteenth century, when no sensible person dreamed of climbing them for pleasure. For Victorian empire builders, the Himalaya was important as a natural frontier, and mapping and measuring it was a handy way of laying claim to the territory. Hence the Great Trigonometrical Survey, George Everest’s 750-mile “grid-iron” of triangulated calculations of the heights and positions of all the peaks. Like every other Himalayan enterprise, taking the measurements was a bone-wearying business, involving hardship, brute labor, cold, hunger, and exhaustion, as well as technical skill in using heavy equipment such as sight poles, which they lugged to the 15,000-to-20,000-foot summits.

The survey was a triumph of doggedness over adversity and also a major step in establishing the boundaries of the Raj. While the work was in progress, the cartographers either numbered the peaks or used the local names. When all the measurements had been calculated and the maps had been drawn, Peak XV was established as the highest of them all. In honor of the Great Trigonometrical Survey and its recently retired supervisor, they named it Everest.

For Westerners, the Himalaya and the once closed kingdoms that contain it—Tibet, Nepal—have always seemed enticingly strange: not only a romantically distant land with mountains twice as high as the highest Alps, but also a great blank sheet on which to project whatever fantasy one possesses. In the early days, merely getting there was a major undertaking: a five-week sea voyage to Calcutta, an eighteen-hour train journey to Darjeeling; then there were guides and interpreters to be hired, people to cook and clean and set up camp, columns of porters to carry the gear, and a six-week trek into the hills. For those not employed by the Raj, the Himalaya was the preserve of the very rich—or rather, of an exclusive subdivision of adventurers so rich that hardship itself was an adventure.

They came in many forms and with varying degrees of eccentricity. At the turn of the century, for example, Fanny Bullock Workman, a formidable New England heiress, climbed a number of challenging peaks with her elderly husband—she clad in “woolen skirts and hobnailed boots”—and set an altitude record for women climbers that lasted thirty years. Around the same time, the dottiest of all mountaineers, the infamous Aleister Crowley, aka “the Great Beast 666,” joined an attempt on K2 and lived up to his reputation as “the wickedest man in the world” by pulling a gun on a fellow climber.*

Advertisement

The grandest of the early Himalayan expeditions, and also the least eccentric, was that of Luigi Amadeo, Duke of the Abruzzi, in 1909. Amadeo was an explorer, sportsman, accomplished climber, and grandson of the king of Italy. He brought with him a team of four guides, three porters, a cartographer, and a doctor, all of them Italian. He also brought with him

13,000 pounds of stores and equipment: everything from clothing and climbing gear to food and medicine, cameras, photogrammetric survey supplies, meteorological instruments, and more, all in seemingly limitless profusion.

It was a vast load that required three hundred Ladakhi and Balti porters and sixty transport ponies to carry.

More importantly, his team included Vittorio Sella, one of the greatest of all mountain photographers, who immortalized the expedition in a series of brilliant, atmospheric pictures. The duke’s purpose was to climb K2; “the indisputable sovereign of the region,” according to the expedition’s chronicler, “gigantic and solitary,…jealously defended by a vast throng of vassal peaks, protected from invasion by miles and miles of glacier.” K2 is now reckoned to be the most difficult of all the eight-thousand-meter peaks, and by far the most dangerous; to date, only 305 climbers have reached its summit and at least seventy-six have died trying. The duke’s attempt failed, but in other ways it was a triumph: his scientists gathered their data as planned, and Amadeo himself proved that survival at great altitude was possible by climbing higher and staying up there longer than anyone before him. He also left the Abruzzi name on a major ridge, thereby establishing Italy’s claim to K2, which was duly honored, though not until 1954.

The Italian expedition was a model of style and efficiency but the duke had gone to the Himalaya in the same spirit as he had gone climbing in Alaska and the Ruwenzori—for the fun of it, for adventure, and without ulterior political motives. Not so the British, for whom Everest was a matter of national pride, a continuation of the Raj by other means. They had created an empire on which the sun never set, but their explorers had failed to reach the North Pole and had been beaten by the Norwegians in the race to the South Pole. That left Everest, “the Third Pole”: “Amundsen’s undisputed conquest of the South Pole,” say the authors, “and, even more, the poignant defeat and death in retreat of Robert Scott…seized the public imagination.” Everest had a great deal in common with the two poles: it was lethally cold and in its thin air every upward step required a physical effort no less relentless and exhausting than manhauling a heavy sledge across the polar ice. That made it an ideal testing ground for virtues the British valued most: fortitude, perseverance, and the kind of docile courage with which early explorers uncomplainingly suffered unspeakable hardships.

All those qualities were tested to the breaking point during World War I, then tested again at high altitude in the Himalaya. Everest offered “a few lucky survivors one more chance to die gracefully for their country,” and they did so in the same dogged way in which they had fought the war:

[Their plan in 1922] called for advance by stages, laying and stocking through repeated marches a series of six ascending camps or depots roughly five miles apart on the glacier and 2,000 vertical feet apart on the mountain…. The true inspiration for this cumbersome business seems to have been the British Army’s incremental experience of the western front. “In this Polar method of advance,” wrote John Noel [the expedition photographer], “there is an essential psychological principle to be maintained. Each advance, each depot built, must be considered as ground won from the mountain. It must be consolidated and held, and no man must ever abandon an inch of ground won, or turn his back to the mountain once he has started the attack. A retreat has a disastrous moral effect….” One could hardly ask for a clearer articulation of the Great War mentality; in laying siege to Everest in this way, the 1922 expedition established a military model for Himalayan mountaineering that lasted half a century. And this despite its patent failure in 1922.

Isserman and Weaver have no time for mindless obedience or stiff upper lips, nor for the cult of heroic failure and “the high rhetoric of empire and war [that] took over” in 1924, when the deaths of George Leigh Mallory and Andrew Irvine were made public and the two young climbers became “the glorious dead” and Everest “the finest cenotaph in the world.”

By the time he died, Mallory was on his third attempt at the mountain and knew how much hardship was involved. He was also in love with the place. For a climber accustomed to the Alps, the sheer scale of the great Himalayan peaks was irresistible: Everest is not just higher than Mont Blanc, it is almost double the height—higher by two and a half miles—12,000 vertical feet from Base Camp to summit, with approach marches reckoned in weeks, not hours, and routes measured in miles instead of feet. For a climber like Mallory, who had the stamina of a marathon runner, it was heaven. It was also beautiful and for Mallory, as for his Bloomsbury friends, beauty mattered:

We caught the gleam of snow behind the grey mists. A whole group of mountains began to appear in gigantic fragments. Mountain shapes are often fantastic seen through a mist; these were like the wildest creation of a dream. A preposterous triangular lump rose out of the depths; its edge came leaping up at an angle of about 70° and ended nowhere. To the left a black serrated crest was hanging in the sky incredibly. Gradually, very gradually, we saw the great mountain sides and glaciers and arêtes, now one fragment and now another through the floating rifts, until far higher in the sky than imagination had dared to suggest, the white summit of Everest appeared. And in this series of partial glimpses we had seen a whole; we were able to piece together the fragments, to interpret the dream.

Were Everest “1,000 feet lower it would have been climbed in 1924. Were it 1,000 feet higher it would have been an engineering problem,” said Peter Lloyd, a member of another unsuccessful Everest expedition, in 1938. At 29,000 feet, Everest is already nudging the jet stream; if winter comes early the jet stream drops from 30,000 feet to 26,000, the temperature drops with it, and the wind blows so fiercely that it is hard to move at all, let alone to climb. That compounds the debilitating effect of high altitude that reduces the strongest to slow motion and makes even easy rock problems seem extreme. The ability to climb technically difficult rock at great altitude is a very rare gift, even among experienced Himalayans for whom the simple business of moving upward, one exhausted step after another, is already a great test of courage, obstinacy, and true grit.

All the early expeditions had those qualities in abundance but the British wanted to climb Everest in the same style that they climbed in the Alps: casually and sportingly, in the spirit of adventure, and strictly as amateurs, with inadequate clothing—tweed and wool and Burberry—and primitive equipment; Mallory used oxygen but would have preferred not to because he thought it was cheating. Like other members of the Alpine Club, he also disdained newfangled Continental gear like pitons and carabiners, “those conjoined miracles of simple technology,” Isserman and Weaver call them, “that made possible the placing of points of belay on an otherwise sheer face.” With equipment like that, steeper, more daring routes were possible, but it wasn’t trench warfare and it wasn’t sporting, so they left the newfangled to Continental climbers.

The Germans had already climbed outrageously hard north faces in the Alps and now, in the wake of military defeat and the vengeful Versailles Treaty, they wanted to restore their national pride by climbing a major Himalayan. Their 1929 team was led by Paul Bauer, one of Hitler’s early converts, the mountain he chose was Kangchenjunga, and the route was brutal—harder and steeper than anything that had been attempted before. His team performed wonders, tunneling under ice towers they couldn’t climb, digging ice caves when they couldn’t pitch tents, and they seemed poised for the summit until the always unpredictable Himalayan weather suddenly changed:

A violent blizzard struck the ridge, pinned them down for three days, and finally forced them into a memorable death-defying retreat…but not before [Bauer] had infinitely raised the technical standard of Himalayan mountaineering and restored to his own satisfaction the tarnished honor of his countrymen.

Bauer’s example encouraged other climbers who had no taste for overequipped, military-style expeditions. Foremost among them were Bill Tilman and Eric Shipton, two free spirits who traveled light, climbed for pleasure rather than national glory, and were the first British climbers to treat their Sherpas, in Shipton’s words, as “fellow mountaineers rather than servants.” Tilman was a shy, taciturn man, famous for his spartan habits and austere principles, such as “anything beyond what is needed for efficiency and safety is worse than useless”; and “any expedition that cannot be planned on the back of a used envelope is over-organized.” Both of them had the British gift for understatement: they went on “trips,” not “expeditions,” though on one trip they took, in 1935, after another unsuccessful Everest reconnaissance, they climbed twenty-six peaks over 20,000 feet.

It was an extraordinary achievement by two brilliant mountaineers and it made Shipton the natural choice to lead the 1953 British Everest expedition. But the circumstances were not to his liking. The French had climbed Annapurna in 1950; the Swiss had failed just short of the summit of Everest in 1952 and were due to try again in 1955; the French were lined up for 1954; so 1953 looked like England’s last chance. But Shipton was a private man who abhorred publicity and the competitive element in mountaineering; he also had no taste for what he called “the grim and joyless business” of Everest. So the leadership went to John Hunt, who turned out to be the perfect man for the job: a natural leader, sympathetic, good-humored, charming, and with a knack for putting people at their ease; he was also a professional soldier who knew to how to organize men and supplies and understood the intricate planning and strategy needed to make the complicated machine of a large expedition run smoothly, culminating in the account of Hillary and Tenzing.

The conquest of Annapurna by the French, followed three years later by British success (at last) on Everest by Hillary and Tenzing, were like Chuck Yeager’s breaking of the sound barrier in 1947 and Roger Bannister’s four-minute mile in 1954: they broke a psychological barrier about how much the human body could withstand and at what altitude it would cease to function. Before 1950, none of the eight-thousand-meter peaks had been climbed; five years later, twelve of the fourteen giants had fallen, though only to costly military-style expeditions in the old tradition, with teams of climbers and long trains of heavily laden porters. It took another quarter-century, plus a vast improvement in gear, training, and technique, before Shipton and Tilman’s casual, low-key approach to high-altitude climbing became the model for ambitious climbers. Twenty-five years after Hillary and Tenzing reached the summit of Everest, the great Tyrolean mountaineers Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler repeated the climb without oxygen or fixed ropes, and in record time. Messner went on to climb all fourteen eight-thousand-meter peaks, many of them solo, including a solo ascent of the north face of Everest in strict Alpine style, carrying everything he needed—lightweight tent, sleeping bag, stove, and basic rations—on his back.

Messner was just one of many mountaineering supermen who arrived during what Isserman and Weaver call “The Age of Extremes” when technically difficult new routes were climbed in increasingly fierce conditions. Polish climbers set new standards for toughness and bravery by making ascents of Everest and other eight-thousanders in winter, when temperatures sometimes went to fifty degrees below zero. But that was during the cold war when, as one of them said, “Our life [in Poland] is so hard that for us Himalayan climbing is by comparison luxurious.”

That style of irony and self-deprecation were never qualities Messner aspired to. On the contrary, he was his own most enthusiastic fan:

It is true what my critics say: my market value increases with every new supreme achievement, with every new record and with every razor edged situation that I survive…. I allow my person to be used for advertising, I give lectures and I make films—all for an appropriate fee. My death is the only thing that cannot be made to sell—at least not by me.

Such vanity set the tone for a new period of Himalayan mountaineering when the achievements of the climbers and difficulty of the routes began to matter less than the publicity they generated. By 1996, Everest had become a media circus, with eleven expeditions set up in Base Camp below the Khumbu Icefall:

Five of the expeditions had their own Web sites. The Fischer expedition Web site was cosponsored by NBC broadcasting and was maintained on Everest by expedition member and New York City socialite Sandy Pittman. She helped provide Internet users with virtually up-to-the-minute reports on the progress the expedition was making toward the summit, plus interviews with the climbers and photographs.

Mountaineering has traditionally been a pastime for misfits. Yet paradoxically, one of the pleasures of climbing is companionship, which old-timers used to call “the spirit of the hills” and the French called une affaire de cordée: that is, two climbers roped together, each relying on the other, sometimes in dicey situations. It’s also expected to be fun, though no one ever went to climb in the Himalaya with that in mind. The mountains are too big, too high, too remote. Unlike the Alps, they have no strategically placed refuge huts, no cable cars to shorten the uphill slog, and no comforts at all to alleviate the squalor, drudgery, and sheer exhaustion of life at high altitude and in intense cold in a place where there is only rock and snow and ice, and nothing ever grows. In such harsh environments minor tics become intolerable intrusions, and even the best of friends may end up enemies.

Once upon a time, the psychopathology of expedition life was a problem climbers kept to themselves. But manners change and these days, when travel is cheap and climbers go to the Himalaya with as little fanfare as they go to the Alps or the Rockies, bad blood and outrageous behavior are the new fashion. They make good copy and help sell what Isserman and Weaver call “climb and tell” books in which “bruised feelings and simmering resentments were beginning to replace frostbite and hypoxia as the signature ailments of high-altitude mountaineering.” Here is an example of the new style spirit of the hills during the disastrous 1996 season on Everest in which eight people died:

Three Indian climbers were trapped high on the Northeast Ridge on May 10, and early the next morning a Japanese party intent on the summit walked past them, though they were still alive. By the time the Japanese descended, one of the climbers was dead, another missing, and a third barely alive and tangled in his rope. They removed the rope from the survivor but made no effort to help him down the mountain. He too would die. “Above eight thousand meters,” one of the Japanese climbers offered by way of self-justification, “is not a place where people can afford morality.”

Aleister Crowley would doubtless have been proud of them and Jerry Springer might have used them on his show, but their antics make a depressing end to a fine book by two mountain lovers with a strong sense of right and wrong.

This Issue

July 2, 2009

-

*

Three years later, in 1905, Crowley led a disastrous expedition of his own to Kangchenjunga that resulted in four deaths. Crowley, who had heard their “frantic cries” when they fell, chose to stay in his tent: “A mountain ‘accident’ of this sort is one of the things for which I have no sympathy whatever,” he wrote. The next day he further reinforced his reputation for wickedness by climbing straight down past the scene of the accident without pausing to see if anyone had survived. ↩