Britain is a very changed country; it has changed morally. It might be said that its people’s sense of what life is all about has altered more in the last fifty years than it did in the previous 250, beginning in 1709, when Samuel Johnson was born at Lichfield. Yet one of the things that hasn’t changed is the popularity of the nation’s most popular word: “nice.” When I was growing up, everything worth commenting on could probably be described either as “nice” or, controversially, “not nice.” My mother would invite me downstairs for a “nice cup of tea” before I went off to school to be taught lessons by “that nice teacher of yours.” At the same time, Prime Minister Edward Heath, who had “a nice smile,” was “not being nice to the unions.” Tony Blair seemed “very nice” at first, but he wasn’t very nice to his friend Gordon Brown. “Nice try,” my old headmaster would say if he read this very paragraph, “but your diction could be nicer.”

In his Dictionary of the English Language, Johnson does not yet recognize the power of “nice” as the catch-all term for British near-approval, but he produces one of his little gems in defining the word: “It is often used to express a culpable delicacy.” It may be time to observe that Dr. Johnson, neither by his own definition nor by ours, could ever properly have been described as nice. He lacked culpable delicacy to the exact same degree that he lacked good manners, an easy disposition, a sunny outlook, a helpful quality, an open spirit, a selfless gene, a handsome gait, or a general willingness to put his best foot forward in greeting others. If niceness was the only category known to posterity, we would long since have lost Johnson to the scrofulous regions of inky squalor, for he could be alarmingly rude.

At his height he was pleased to savage everybody who came within goring distance: he put down lords, ladies, friends, and biographers, and would not have hesitated to “talk for victory” in the face of a five-year-old child. His needs were gigantic and gigantically exposed. Like so many authors, but none so much as him, he had no idea how he could sometimes sound to other people, enlarging himself at every turn, propagating his own reputation in such a way as merely to extend, as Johnson admitted himself in one of his own essays, “the fraud by which [such authors] have been themselves deceived.” Johnson’s writing tended toward the promotion of ideals of human conduct that he himself could never attain. But he fails most signally on the lower ground, the ground of niceness, toleration, selflessness, never setting the world at a distance from himself the better to contemplate it, but rather roughing the world up every time it got too close. He wanted to show his greatness and wanted nobody much to delay him.

Johnson started the habit early, being a font of arrogance and ill-attendance with his tutor when still an undergraduate at Oxford. When the Reverend Jordan, a senior fellow at Pembroke College, confronted Johnson with his absences, the young boor was something less than apologetic: “I answered I had been sliding [skating] in Christ-Church meadow. And this I said with as much nonchalance as I am now talking to you.” His friend Mrs. Thrale noted that “he laughed very heartily at the recollection of his own insolence.”

This early report is given by Peter Martin in a lively new biography, a book well seasoned with good stories, most of which do not seek always to show the Doctor in a better light. (This was a habit of James Boswell’s that has not been adhered to by the biographers coming after him, nor, it might be said, by those immediately preceding him. Sir John Hawkins appears to have rather enjoyed offering the reader a comprehensive tour of the Doctor’s warts.*) Martin is sympathetic to Johnson and equally sympathetic to the truth about him. He has hitherto written excellent biographies of both Bos-well and Edmond Malone—two of the Doctor’s brightest satellites—and he turns to Johnson with a strong and nuanced sense of how he was, as much as anything, the figment of a great many busy pens, not least his own.

Our hero often saw the world, or the world of literature anyhow, as scarcely being worthy of him, but what we see from the new books by Martin, Jeffrey Meyers, and David Nokes is a Johnson constantly in a state of application to the business of authorship. Anyone who cares about that subject, or who perhaps has a continuing experience of its joys and displeasures, will find the three-hundredth-anniversary turn toward Johnson’s brilliance as an author quite welcome, for he has been too long covered in anecdotage and too long unread by the public.

Advertisement

But I am not yet done with his bad character. He left Oxford like a wounded bear, the injury being pride—he lacked the money to continue his studies or gain his degree—and spent time in Birmingham with Edmund Hector, a friend from his school days. Hector spoke of Johnson there being “withdrawn, heedless, or neglectful,” talking to himself in “peevish fits,” a habit of emotional insolvency he carried into his marriage with the famous Tetty. He was very often away from her for many months at a time, subjecting her to woes and neglect, contempt and poverty, while he made a fuss over other women and better minds. At the same time, as a reviewer, he could be nearly psychotic in the scale and brutality of his dispraise, not only calling books and individuals to account but molesting them unawares and pounding them into dust.

The great moralist wanted for nothing as a great reviewer in the Age of Reviews, except for shame of course, arguing in one place against the “elation of malignity” while himself wielding what Martin calls “the club of Hercules” in a one-man Colosseum of hostility, violence, intemperance, and abuse. Besides Alexander Pope, it is hard to think of an author of his period who so enjoyed the terrible spectacle of other people’s dullness, or who invested more anger in his moment to shine. It was an aspect of his daily life commented on by Mrs. Thrale, who, despite all her kindness to him in old age, suffered a barrage of blame and derision:

She protested that helpful as he was with Queeney and later the other children, he was insufferably opinionated in advising her how to bring them up…. At first, she felt it was all worth it because she and her husband saw themselves as saving him; later, she chafed under a “perpetual confinement” that was “terrifying in the first years of our friendship, and irksome in the last.” She insisted that after her husband’s death in 1782, she could scarcely bear his capriciousness and roughness in the house.

Mrs. Thrale had powers both of forgiveness and self-interest, and she was often able to overlook his abuses, but not everybody could. (Even Johnson found it hard to forgive himself.) Boswell’s wife Margaret never loved Johnson—not surprising, given the size of her husband’s admiration—and neither did Lord Auchinleck, the whole of Scotland, Horace Walpole, and half of English society. As Peter Martin reminds us, Walpole went out of his way to avoid Johnson, only finding time to describe him as “an odious and mean character” whose “gross brutality” made Walpole want “to fling a glass of wine in his face.” The failures of niceness were multiple and seemingly endless, but out of that gloom comes a man so brilliant and various, so imaginative and original, that he proves a friend to everyone who cares about the English language and a mentor to everyone who is amused, repelled, or averagely engaged with the problems of human nature.

On the eve of his three-hundredth birthday, Johnson’s glory lives in his multiplicity. He was never one thing. He was Janus-faced but also Janus-souled: investing as much of himself in the opposite of rancor and enmity as he did in rancor and enmity, and sometimes within the same half-hour. It is the main reason why James Bos-well was able to make him the subject of the best biography ever written: the two-minded biographer met his four-minded subject and a form of literary intimacy was born that time has neither breached nor weathered. Let us see it at work. During a coach ride to Twickenham, Boswell noticed how badly Johnson knew his own character, but he could observe that “Johnson’s roughness was only external, and had no participation with his heart.” They proceeded then to have what is essentially a conversation about the vicissitudes of niceness:

JOHNSON: “It is wonderful, Sir, how rare a quality good humour is in life. We meet with very few good-humoured men.” I mentioned four of our friends, none of whom he would allow to be good humoured. [We know from Boswell’s notes that these were Oliver Reynolds, Edmund Burke, Mr. Beauclerk, and Mr. Langton.] One was acrimonious, another was muddy, and to the others he had objections which have escaped me. Then, shaking his head and stretching himself at his ease in the coach, and smiling with much complacency, he turned to me and said, “I look upon myself as a good-humoured fellow.” The epithet “fellow” applied to the great lexicographer, the stately moralist, the masterly critic, as if he had been Sam Johnson, a mere pleasant companion, was highly diverting; and this light notion of himself struck me with wonder. I answered, also smiling, “No, no, Sir; that will not do. You are good-natured, but not good-humoured. You are irascible. You have not patience with folly and absurdity. I believe you would pardon them if there were time to deprecate your vengeance; but punishment follows so quick after sentence that they cannot escape.”

In our age of indifference, it is hard not to be excited by the notion of Johnson’s morally questing spirit. From the uses of memory to dealing with sorrow, he viewed man as an endlessly vexed and vexatious animal, making life up as he went along and subject to the lowest lows as much as the highest highs. We see it in his behavior, we see it in his Dictionary, where vituperation has its place in the very definitions ( Lexicographer : “a harmless drudge”; Pension : “in England it is generally understood to mean pay given to a state hireling for treason to his country”), but we see it most finely in his essays, especially those published in The Rambler.

Advertisement

It is here that the question of Dr. Johnson’s niceness cedes to larger questions about his humanity and his spiritual capaciousness. We see in those essays the tiny brushwork of brilliant self-portraiture; we hear the rhythm of moral seriousness, the sound of contemplation as it engages with the questions of how to live and how to manage in the face of death. But most of all we feel the reach of an author—a writer attempting to reach past self-doubt, poverty, cant, and orthodoxy, in order to assert the power of individual authorship and free thinking in the face of more nebulous authorities. Samuel Johnson may have failed often enough to be personable, but he nevertheless freed subjectivity, as did his biographer, and brought both dignity and self-sufficiency to the writing game, allowing authors to be who they chose to be, unshackled from patronage and the requirement to please great men. We see it in his essays and we see it again in his Lives of the Poets : a writer’s writer, beckoning individual creative power out of the mire of dependency, making the work answerable only to high standards of excellence stringently applied.

Johnson professionalized authorship not only for England but for the world, making the individual conscience responsive only to its own capacities and its own engagements. Art may often have had a deadline in Johnson’s cosmos—the cosmos of booksellers and periodicals—but that was, and is, something much less small than the vanity of a Lord Chesterfield. The literary world before Johnson was a dense and forelock-tugging place. Here he is in The Rambler, No. 163, on “The perils of having a patron”:

None of the cruelties exercised by wealth and power upon indigence and dependence is more mischievous in its consequences, or more frequently practised with wanton negligence, than the encouragement of expectations which are never to be gratified, and the elation and depression of the heart by needless vicissitudes of hope and disappointment.

Every man is rich or poor, according to the proportion between his desires and enjoyments; any enlargement of wishes is therefore equally destructive to happiness with the diminution of possession; and he that teaches another to long for what he shall never obtain, is no less an enemy to his quiet, than if he had robbed him of part of his patrimony.

Johnson himself had often been so robbed, and I wish that Peter Martin, the editor of Selected Writings, had chosen to include his fantastically snubbing letter to Lord Chesterfield beside these moral essays, along with the poems “London” and “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” None appear, a pity because these works show us Johnson at his most invigoratingly ethical, committing himself to hardship as he asks writers to depend on the favors of their own talent and nothing else. Lord Chesterfield, the dedicatee of the Dictionary, never lifted a finger to help Johnson during the years of excruciating difficulty it took to complete the volumes. (His government pension came much later.)

As has been well said before now, Johnson took nine years to complete on his own what it took forty French academics fifty-five years to produce in the Dictionnaire de l’Académie francaise. It was an inconceivable labor and whatever toll it took on the Doctor’s niceness, however much it enlarged his capacity for bitterness, he created a literary culture of a new sort by insisting—indeed proving—that it is a nation’s great writers who determine the language. He used Shakespeare, Milton, and Dryden at the head of an army of brilliancy; he sourced and copied over 100,000 examples for the Dictionary to best illustrate the meanings and uses of English words. In doing so he revealed a republic of letters as a rich, voluble, human culture, a summit of what men might do to civilize their days and exalt their common circumstances. The Dictionary indeed is a work of art, encapsulating an almost infinitesimal belief in the magic of poetry and prose. The book reveals nothing less than a living culture represented by marks on paper.

That is why Johnson is important: he is the patron saint of literary faith. And our love of him can only increase when we see, as we do once again in these fresh biographies, what agonies and doubts accompanied his efforts to write well and live better. Johnson’s curmudgeonly nature thankfully makes him no easy subject for saint-makers, but the litany of sufferings he endured is not small, making his achievements appear all the greater for having come from a body so wracked with tics and distempers.

Jeffrey Meyers has written more than a few biographies of writers—Hemingway, Orwell, Robert Frost, Katherine Mansfield, and nearly a dozen others—so I imagine him to be an expert on authorly sufferings both real and imagined. He has a great deal to say about his subject’s unhappiness, but perhaps Meyers pegs it a little too far down from the mental heat of a life’s metaphysical inquiry. What we get is a more salacious Johnson, a randy genius who supplies plenty of evidence to those who would see his obsessions with confinement and severity as expressing a basic, rather prosaic desire to be tied up and whipped. Meyers’s book goes in for this sort of thing with a certain degree of brio; indeed, not since the publication of Kenneth Tynan’s journals have we been treated to such a suggested litany of unjolly spankings. We like to imagine that our famous critics have a strong requirement for some of their own medicine. I think it hardly likely, but there it is.

The modern Johnson will enjoy the modern ruminations. It is all part of the developing art of biography, which Johnson sought to support with great enthusiasm. James Boswell, for all his own avidity at the sport, was too keen to sanitize Johnson’s sexual involvements with a view to preserving his dignity as an unimpeachable moralist. Of course, Boswell’s biography is the greater for being the original one and the one uniquely suited to its subject’s almost baroque multifariousness, but prejudice against Mrs. Thrale certainly steered Boswell away from any accurate examination of her relationship with Johnson.

The saucy Mrs. Desmoulins had a tale to tell about Johnson’s tenderness toward her, and Boswell went after the story in 1783 in company with the painter Mauritius Lowe. To induce the tale, Mr. Lowe pretended to believe that Johnson had no passion. “Nay, Sir,” replied Mrs. Desmoulins, “I tell you no man had stronger, and nobody had an opportunity to know more about that than I had.” Peter Martin has the biographer and the painter rather comically bolt “upright in their chairs” at this news, “craving more revelations.” There was more to come, about various benign fondlings and heads being laid on pillows, but Boswell, who wrote it up over five pages of his journal, decided to leave it out of the biography. It is perhaps in this context that the biographers of today want to bring the matter out, and they do so with various degrees of relish and panache.

David Nokes has a firm understanding of what goes toward the making of a literary life, and his biography of Johnson—to be published in October—is not merely a crisp rendition of the known facts, but a book that shows the man in some new interpretative light. Nokes goes against conventional wisdom in pointing out that Johnson wasn’t necessarily as obnoxious as many have suggested. His evidence is uncommon but no less interesting for that. He quotes from essays our hero wrote at Oxford, early writing that, far from displaying Johnson’s usual disdain, actually possesses what Nokes calls an “open, unguarded quality.” These undergraduate essays, he argues, are “eager, youthful, a little naive, but optimistic. It is a tone, from Johnson, we should not forget.” It is a good and untypical observation, untypical even of Nokes in his own book. Overall there is a melancholy tone to this most recent of the Johnson biographies, a tone that is not unearned, as they say in the movie industry, given the depressive experience of the subject and the darkness visible in everything he wrote.

Perhaps no other writer has been as much augmented as Johnson has by the biographer’s art, yet, along with Shakespeare, there can be few whose real biography is more fruitfully to be plucked from the pages of their own work. Johnson loved biography and he believed that writers should be willing to examine everything about themselves in the attempt to get hold of human nature. The biographers catch the antics of him, the kindness, the melancholy, the indolence, the enjoyments, the opinions, of course, and his monstrousness, too. But what his own writing captures best is the intellectual grace of the man: the moral point coined with the exact weight and density at the right moment, and freshly imprinted with a human face.

Johnson may have become a superstar of his own life—a fiction in his own afterlife—but he was one of those writers whose substance was never far distant from the work that he did. We see in his essays the grandeur of an oppressed spirit in search of a home, never finding it, never knowing great peace, but always suspecting that the journey is common to humanity. Johnson founded a community of belief about the importance of literature—“he kept a school,” said Boswell’s father, “and called it an academy “—which meant deploying the zeal of Christian devotion to praise a lower sort of creator, the author, and to inspire a different sort of congregation, the readers. Like all Christians he made a fetish of the hereafter, but in his best manners Johnson was an angel of the busy earth, a monarch of the secular, thumping up the public highway with a hunger for life and its literary representations.

That is why he always had an answer to the problems of biography, and also why, perhaps, he was so perfectly suited to becoming one of biography’s great problematicals. He had a particular talent for living, which is the element in great people that Boswell taught all future biographers to capture. Here Johnson is—fresh as this morning—writing in The Rambler, No. 60, on the value of biography:

If the biographer writes from personal knowledge, and makes haste to gratify the public curiosity, there is danger lest his interest, his fear, his gratitude, or his tenderness, overpower his fidelity, and tempt him to conceal, if not to invent. There are many who think it an act of piety to hide the faults or failings of their friends, even when they can no longer suffer by their detection; we therefore see whole ranks of characters adorned with uniform panegyric, and not to be known from one another, but by extrinsic and casual circumstances…. If we owe regard to the memory of the dead, there is yet more respect to be paid to knowledge, to virtue, and to truth.

Thus, long before he was the great subject, Johnson puts a name to those problems facing the good biographer. In a long view both tender and admonishing, he sees the pieties of Boswell as well the excitability of Meyers, the protectiveness of Martin, the searchingness of Nokes, asking them—and all of them in between, Hawkins, Wain, Jackson Bate—to pay attention only to the highest standards and the loftiest goals of interest and revelation. “Nothing is too small for such a small thing as man,” he once said, a legend that should be engraved on the heart of every journalist worth his salt and every novelist worth her ribbon.

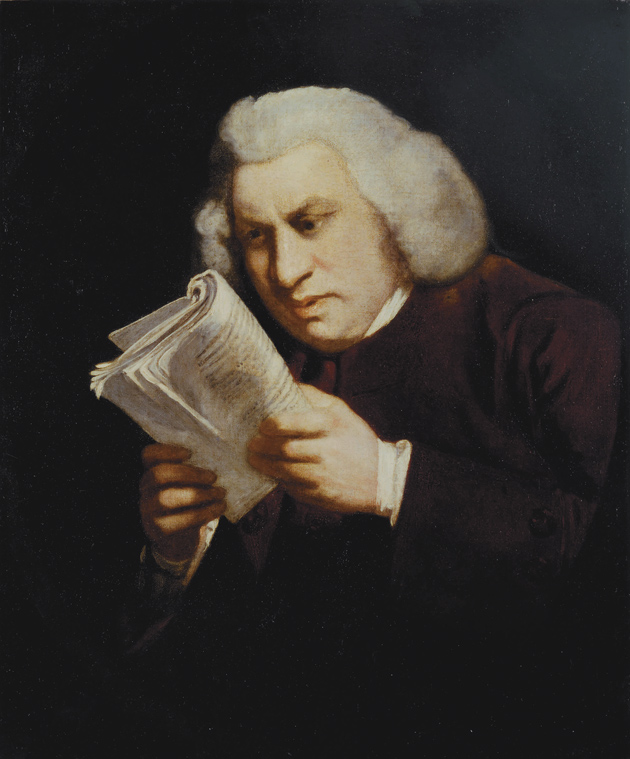

When we look at the life of Samuel Johnson—and his four-times-longer afterlife—we see a ferocity of living coupled with a moral punctiliousness that left him devastated before the prospect of death. In Joshua Reynolds’s famous portrait of our myopic hero—a portrait usually referred to as “Blinking Sam”—we see a man who seems almost consternated by the moral news that literature can provide. Johnson may appear like a crazed workaholic to us, but in his own eyes he was indolent and depressed, slow and uneven in his commitment. Nowadays, when novelists have an article to write or a class to teach, you can hear their wailing from the Equator to the Arctic Circle, as if the demons of drudgery had tied a chain to their lovely bones. Yet Johnson, while half-blind and aching with the gout, in a cold garret and dressed like a mendicant, formed his nation’s dictionary and an entire multivolume edition of Shakespeare with commentary and notes, while also devoting himself to poetry, plays, hundreds of essays, parliamentary sketches, prayers, prefaces, and multiple biographies. In his own judgment, there was much to be done and too slender means with which to do it, but he believed that only work, only application, could justify the claims of a writer. Johnson would smile at the way modern authors can fret for years over their novellas, those who cup their works like they are small birds being carried through a blizzard, the outside world aiming only to maim their precious cargo.

No one should be measured by Johnson’s yardstick, but his general willingness to ink up and face the world might also serve as a good example to those, writers and readers alike, who see no real distinction between the art of writing and the art of embalming, where a little fluid and a lot of solemnity are used to eke out the appearance of the dead. Johnson had the courage to make his life equal to the task of improving the world that sustained him.

In every line he wrote he is alive, which is perhaps why death presented such a terrific challenge to the balance of his mind. “Bright young spirits,” as Peter Martin brightly calls them, “were good medicine for Johnson.” His liking for a late-night debauch was tied to his liking for younger people with whom he could frolic and laugh, chasing away the melancholy business of having to live alone with his thoughts. Johnson hungered for life in a way that could never have allowed him to face death with anything but refusal. He was only forty-one when he reported, in TheRambler, No. 78, on what he saw as the first and last of subjects. “Milton,” he writes,

has judiciously represented the father of mankind, as seized with horror and astonishment at the sight of death…. For surely, nothing can so much disturb the passions, or perplex the intellects of man, as the disruption of his union with visible nature; a separation from all that has hitherto delighted or engaged him; a change not only of the place, but the manner of his being; an entrance into a state not simply which he knows not, but which perhaps he has not faculties to know…the final sentence, and unalterable allotment.

These new biographies will not provide the last word, and there is still a great deal to fall out over. Indeed, last words are something our biographers have yet to agree on. For David Nokes, Johnson’s last words are not doubted. When a young lady was shown into his chamber, Johnson turned in the bed and said, “GOD bless you my dear.” (This was Boswell’s belief.) Peter Martin relies on the biography by Hawkins, which has Johnson waking in his last seconds to say, ” iam moriturus “—“Now I am about to die.” Jeffrey Meyers gives us both options, but appears to invest more belief in the evidence of Hawkins. It is Nokes who sums up, rather delicately, the deepest ambition of all who have taken the Doctor as their biographical task: “He once declared that it was ‘the biographical part’ of literature that he loved; I trust that, in writing this account, I may not wholly have disappointed that hope.”

What we know for certain is that Dictionary Johnson, the Great Cham, the most singular critic of the Augustan age, was not ready to face death. Boswell, so keen a friend, so choice a writer, could not face describing the hell of drugs and potions and blood-lettings that accompanied Samuel Johnson’s last hours. We hear of them now, but beneath them we might hear something more lasting and more resonant: the sound of Samuel Johnson’s great yearning for life.

This Issue

October 8, 2009

-

*

A new, corrected, and annotated edition of Hawkins’s The Life of Samuel Johnson LL.D, first published in 1787, and edited by O.M. Brack Jr., was reissued this summer by the University of Georgia Press. This edition is—as Johnson once said of a previous work by Hawkins on Izzak Walton—”very diligently collected, and very elegantly composed. You will…not wish for a better.” Professor Brack deals with the question of Hawkins’s “asperity” toward Johnson in his introduction. “Hawkins had to decide if he was going to write a panegyric on Johnson or produce a life….Hawkins esteemed Johnson, but he esteemed truth more.” ↩