On May 29, 1453, the armies assembled by the young Ottoman sultan Mehmet II breached the land walls of Constantinople, which had resisted assault for a millennium. By the next morning the invaders had arrived at the doors of the imperial church of Hagia Sophia. The sources speak of plunder and rapine, but also of an act of preservation. As the conquering sultan gazed in awe at the vast resplendent interior, he came across a soldier breaking up the marbles of the floor with an axe. “Wherefore does thou that,” he asked, and the soldier replied, “For the faith.” Mehmet struck him in anger, saying, “Ye have got enough by pillaging and enslaving the city, the buildings are mine.”

Hagia Sophia had been built by the Byzantine emperor Justinian in 532–537 and had served as the cathedral of Constantinople and the central church of the Byzantine Empire for over nine hundred years, but after its forced conversion it entered a new life as an imperial mosque, Aya Sofya Camii. And a mosque it would remain for the next five hundred years. Aya Sofya provided the model for the imperial mosques of Constantinople. It was intensely studied and imitated by the great Ottoman architect Sinan. But as far as Western architecture was concerned, Hagia Sophia effectively dropped out of the canon.

It was extremely difficult for non-Muslims to visit the mosque of Aya Sofya. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century European travelers tell tales of bribery and disguise to gain entrance at risk of life and limb. To make a drawing inside was next to impossible. In 1611–1612, when the French ambassador wanted a portrait of Sultan Ahmet, he took with him to Constantinople a budding artist with a photographic memory, Simon Vouet. He hoped to have Vouet memorize, and then draw in private, not only Sultan Ahmet but also Aya Sofya and the other notable places of the city. Sixty years later the French writer Guillaume Joseph Grelot bribed the guards and hid his artists at gallery level in order to produce a new plan and section, which he published in 1680, the first glimpse Europe had of the church since the conquest. Until late in the nineteenth century men were prepared to pay dearly, and women to cross-dress, for permission to enter the church-turned-mosque.

Not only did the great church disappear from Western consciousness, but Byzantium was reviled in the Enlightenment as a civilization ridden with superstition. The French historian Hippolyte Taine wrote in 1865 of the mosaics of Ravenna—the seat of Byzantine government in Italy—that the saints and angels figured in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo looked like “vacant flattened sickly idiots…great simpletons with staring eyes and hollow cheeks.” Gibbon, writing The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire in 1776–1788, condemned the Oriental despotism and corruption of the Byzantine state and had little good to say of its architecture. Even one of the early defenders of Eastern Christian art, Alexander Lindsay, twenty-fifth Earl of Belcares, writing in 1847, says that his readers are

apt to think of the Byzantines as a race of dastards, effete and worn out in body and mind, bondsmen to tradition, form and circumstance, little if at all superior to the slaves of an Oriental despotism….*

This is the heavy mud out of which a remarkable array of travelers, artists, architects, writers, scholars, and political figures lifted Byzantium and Hagia Sophia in the century between 1850 and 1950. At the beginning of this period Byzantine architecture and mosaic decoration were generally considered Oriental, feminine, decadent, sensuous, and corrupt. By the end they had inspired innovative painting in a wide variety of modern styles, two of the greatest poems of Yeats, and a late masterpiece by Frank Lloyd Wright, the Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin.

Churches everywhere, but also throne rooms in Germany and statehouses in America, were built with the flat domes, gold ground mosaics, bright marble columns, and apses within apses that recalled Hagia Sophia. When the Greek widow of Louis Pasteur came to choose a style for her husband’s mausoleum, now the centerpiece of the Institut Pasteur in Paris, she turned to the symbol-drenched world of Byzantium and had the saga of her husband’s battle with rabies depicted in colorful mosaics. And when Seth Low wanted to convince the trustees of Columbia University to build the great rotunda known as Low Library in the center of the campus, his architect, Charles Follen McKim, held up a large photograph of the dome of Hagia Sophia.

The two books under review chart the phenomenon of the Byzantine revival, the understudied successor to the Gothic revival. Though they traverse common ground they are quite different in tone and organization and make a good complementary pair. J.B. Bullen, a literary scholar who has previously explored the historiography of the Renaissance in the nineteenth century and written on many pre-Raphaelite themes, here turns art historian, organizing his book, Byzantium Rediscovered, around the great stylistic shift toward Byzantium in the later nineteenth century.

Advertisement

In four magisterial chapters Bullen gives us the story of the Byzantine revival in Germany, France, Britain, and the United States. Each chapter tends to begin with forerunners in the 1820s and 1830s, critics who revive Byzantium from the opprobrium of Gibbon. Then he turns to the historiography of the Middle Ages and in particular of Byzantium in each country. One finds beautiful photographs and insightful descriptions of hundreds of interiors that achieve sensuous coloristic effects with gold ground mosaics and precious marbles. The author is especially alert to the strange confluence of Byzantinism and modernism in the first decades of the twentieth century, and provides a new setting for the work of Klimt, Matisse, and French symbolist painters like Maurice Denis. Bullen is eloquent about art but also widely read, and one finds mention of virtually every nineteenth-century book in English, French, or German that ever treated the art of the eastern Mediterranean. He explores fascinating junctures of nationalism, Orientalism, historiography, nation-building, and theocratic kingship.

Robert S. Nelson, on the other hand, is a Byzantinist, an art historian who writes on Greek manuscripts and icons and who brings to the task a knowledge of the vast literature surrounding the Byzantine world in general and, in particular, Hagia Sophia. Formed in the school of the historian Arnaldo Momigliano, he is also a student of historiography, and open as well to the theoretical implications of Orientalism. He is interested in the ways in which a monument is created, and he is alert throughout to the history of photography and book design. His story in Hagia Sophia, 1850–1950 is a majestic one, the recovery of Byzantine civilization in the consciousness of the West. But he is also curious about the pre-history of his own field. He combines both these concerns in dealing with a central theme, the reception of Hagia Sophia in modern times.

The 1840s and 1850s were crucial years in the formation of a new view of Byzantine art. Some of the key figures traveled to Byzantium, but many did not. In 1829 Lord Lindsay began the travels that would lead to his book on Christian art with a visit to San Marco in Venice, and he later visited Mount Sinai, where the monastery of St. Catherine held a treasure trove of icons that had escaped the wave of Byzantine iconoclasm of the eighth century. He developed an elaborate racial theory in which Byzantium represented the contemplative element of the original European character, as Rome did the practical. The cupola of Hagia Sophia was in his vision the crown of glory of Byzantium, which vindicated the dome as a Christian architectural form for the rest of time.

John Ruskin reviewed Lindsay’s book while an undergraduate at Oxford. Though skeptical of its larger theories, he drew on it as the first unbiased estimate of Byzantine art. The seed it planted blossomed in 1853 in his Stones of Venice. Ruskin never traveled to Constantinople but extrapolated from his intimate knowledge of San Marco in Venice. This became for him the paradigmatic Byzantine building, superior to anything else produced in the West.

Both authors rightly stress the centrality of Ruskin in the Byzantine revival. For Bullen, Ruskin’s language is effusive and even erotic, with a range of linguistic “voices” far greater than Lindsay or any writer up till then. He employs those voices to entice, to fascinate, and to convert his readers. Nelson stresses instead Ruskin’s geological and minerological acuity and the biblical resonances of a book in which the very stones cry out, in which the geology of the Venetian region is studied and the colors of the imported stones are described and mosaic analyzed as painting in marble. Ruskin took San Marco, a building despised by the Gothic revival, and convinced the British public that it was “as lovely a dream as ever filled human imagination” and a model worth copying.

The 1850s saw a renewed interest in Hagia Sophia by scholars and architects willing, unlike Ruskin, to travel east. A progressive Ottoman sultan, Abdülmecid, decided to raise the standard of architecture in the capital by commissioning a new university from two Swiss architects, the brothers Gaspare and Giuseppe Fossati. They had already built the Russian embassy in Istanbul, and after the success of the university, Abdülmecid invited them to restore Aya Sofya Camii. The project lasted from 1847 to 1849 and involved as many as eight hundred workmen. The Fossati consolidated the structure, painted the exterior with the horizontal stripes that can be seen in old photographs, and gave the interior the colorful decorative frescoes and huge roundels with verses from the Koran that we see today.

Advertisement

The Fossati uncovered splendid mosaics that had been whitewashed in the early eighteenth century. From their scaffolding one could contemplate once again, as in the heyday of Byzantium, the Virgin and Child in the apse, a giant warrior angel on a nearby arch, the fathers of the Church on the side walls, and donor portraits of a number of Byzantine emperors and empresses. Abdülmecid was deeply moved, but also afraid that his reforms might be going too fast for his countrymen and the time not yet ripe for such a revelation. So he told his architects to cover the mosaics up again. They would stay hidden for another eighty years, between 1849 and 1932, until revealed once again in the restoration campaign of the Byzantine Institute of America.

In spite of Abdülmecid’s fears, two colorful books showed the newly restored Hagia Sophia to the Western world. Though the Fossati brothers never produced the definitive publication of their findings, in London in 1852 they published a portfolio of twenty-five picturesque lithographs showing Aya Sofya as a functioning mosque, carpeted from wall to wall and filled with turbaned faithful. The restoration by the Swiss architects and the book published in Britain paradoxically gave the church much of its Oriental allure. The other book was unofficial but more “scientific” in its illustrations. The Prussian architect Wilhelm Salzenberg was in Constantinople at the time of the Fossati restoration and returned to Berlin with drawings of the uncovered mosaics in 1848. His great volume on the church shows some of the mosaics that had been covered up just after his departure. The book was published in Berlin in 1855 and is intimately bound up with the Prussian interest in early Christian and medieval art.

The Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm IV, the “Romantic on the throne,” amateur architect, and lover of the Middle Ages, along with his brother Prince Karl, brought the medieval and Byzantine revival to Berlin in the 1840s. They bought up mosaics and sculpture from a crumbling church in the Venetian lagoon and shipped them to their villas around the lakes of Potsdam. Both Bullen and Nelson dwell on the fascinating convergence between absolutist political philosophy in Prussia and the Byzantine revival in architecture. Nelson in particular points out the irony of the situation. Abdülmecid had ordered the restoration of Hagia Sophia as part of a program of progressive reform, while Salzenberg’s publication supported the conservative reaction of the Prussian monarchy: “For once, the East looks forward; and the West, backward.”

Bavaria, Prussia’s rival within the emergent German nation, had its own Byzantine revival, patronized by two autocratic rulers, Ludwig I and his grandson Ludwig II. Byzantine theocracy as a model for modern kingship exerted a spell over both, but it was Ludwig II, the repressed homosexual obsessed with secrecy about his inner life, for whom Byzantium offered the perfect style of rulership. In Bullen’s lively account we see how Ludwig II became a close, passionate friend of Richard Wagner and a devotee of Germanic myth. As Wagner was writing Parsifal, the King became fascinated with the Holy Grail. He had a number of brilliant scenographers and architects design a Grail Hall for Graswang, one of his Bavarian palaces. Not immediately built, this neo-Byzantine design eventually metamorphosed into the throne hall of Ludwig II’s famous fairy-tale castle at Neuschwanstein. Here, on top of a mountain, under soaring Gothic towers, one enters Romanesque portals to penetrate deep in space and back in time to a soaring domed hall, full of light and brilliant color, a miniature of Hagia Sophia. Here the Parsifal king would have sat enthroned in the apse, had he not ended his life in the waters of the Starnberger See before the room was finished.

Both books explore the fascinating interplay between Byzantinism and twentieth-century modernism. They show how attractive one or another aspect of the style was to Gustave Moreau, Cézanne, and the entire Symbolist movement. Nelson reminds us that Matisse was a friend of Thomas Whittenmore, the man who uncovered the mosaics of Hagia Sophia. The great French Byzantinist Charles Diehl knew how to write on Byzantium in a style that would move any spirited artist:

Under the golden domes of Justinian’s church, every Byzantine experienced emotions…as deep and as powerful and his mystic and pious soul became marvellously exalted.

The spell that Byzantium cast over the modern imagination finds no better expression than in two poems of William Butler Yeats, “Sailing to Byzantium,” of 1926, and “Byzantium,” of 1930. They have a rich literature of their own and both of the books under review scrutinize them closely. Nelson has a fascinating chapter showing how the Celtic visionary wove his magical vision out of memories of his visit to the Cappella Palatina in Palermo in 1924 in addition to an earlier visit to Ravenna in 1907, as well as photographs he found in Dalton’s 1911 handbook on Byzantine art.

Yeats was sixty-one when he wrote “Sailing to Byzantium,” three years after his Nobel Prize and two years after a visit to Italy and Sicily. He already thought of himself as an old man, “a tattered coat upon a stick,” impotent in a land of rampant sexuality. Yeats found his image of the freeing of the purified soul in a journey, which he himself never took, to Hagia Sophia, where he would be gathered “into the artifice of eternity.”

In both books one finds persuasive readings of the poem against the larger cultural background of the Byzantine revival. Bullen not only reminds us of Yeats’s travels to Byzantine monuments in Ravenna and Sicily but also shows us the Byzantinizing mosaic decoration of the Golden Hall in the Stockholm Stadhus, carried out in 1923 by Einar Forseth and much admired by Yeats when he visited it on the occasion of his Nobel Prize.

Nelson, on the other hand, examines the manuscripts to chart the long genesis of the poem. He shows how Yeats, in his early drafts, put the poet in a boat with mariners, deposited him in the imperial harbor, and had him look up at the “ageless beauty” of St. Sophia’s sacred dome. In later drafts the mariners, boats, dolphins, and harbor all disappear and the journey becomes an interior one, in which the soul tears itself away from the “dying animal” of a body to be purified by images of Byzantine saints, “sages standing in God’s holy fire,” “singing-masters of my soul.” Never again for the purified soul another human body, but only “such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make/Of hammered gold and gold enamelling,” an image inspired by the photograph of a precious Byzantine gold and enamel book cover in Dalton’s handbook. The scholar saw in the book cover a symbol of the “life elect and spiritual,” and the poet who never visited Byzantium made it into art.

Hagia Sophia and then Aya Sofya were never far from the center of politics. In the delicate situation after World War I, when a defeated Ottoman Empire was being dismantled, factions in Greece hoped to regain some of its historically Greek territories with their Greek-speaking populations, and perhaps even take back Istanbul and make Hagia Sophia into a church again. Britain’s philhellene foreign secretary, Lord Curzon, former viceroy of India, was a supporter of “the Great Idea,” the catchword for Greek irredentist claims to Constantinople. Backed by the weight of British gunships, the Great Church might be, in the words of the Greek folk song, “ours once more.” As the leaders of the Young Turks from Istanbul escaped to the center of Anatolia, out of range of the British, to found the capital of modern Turkey at Ankara, they considered threatening to blow up the building if the Greeks should attempt to take it back. Mosque or church? It seemed an issue that only war would settle.

The story of how Aya Sofya Camii became a museum, belonging to neither Christianity nor Islam, is the subject of one of Nelson’s most interesting chapters. It starts with the purchase of a Byzantine silver chalice in Paris in 1913 by the American writer and diplomat Royall Tyler, who communicated his enthusiasm for all things Byzantine to two rich friends in the diplomatic corps, Robert Woods Bliss and Mildred Barnes Bliss, who were swept up by his passion for Byzantine art. Into their world came Thomas Whittemore, an American amateur with a talent for friendship with people in high places. Litterateur, archaeologist, Egyptologist, fund-raiser for an ambulance corps in Russia in World War I, Whittemore collected patrons for humanitarian causes who would later be enlisted in his scholarly ambitions. All the while Whittemore’s love for Byzantine art was growing. It was combined with an aesthetics propounded by the Japanese writer Okakura in his Book of Tea, and there are links in Whittemore’s youth with Isabella Stewart Gardner in Boston, the Berensons at I Tatti, Roger Fry in London, and Matisse in Paris.

Eventually in 1931, with the help of American diplomats he had met during the war, Whittemore convinced the young republic of Turkey to give his Byzantine Institute of America the concession for the restoration of Hagia Sophia. In 1932 he won the friendship of the Turkish leader Mustafa Kemal. On November 24, 1934, the day that Kemal was declared Atatürk, father of his country, Aya Sofya was secularized. As a museum, not a church or a mosque, it left the realms of religion and warfare. In a decades-long campaign, the mosaics that the Fossati brothers had seen in 1847–1849 but then covered up were definitively revealed. Copies were made and sent around the world. One can be seen today high up over the gallery of arms and armor in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, testament to Whittemore’s vision and persuasiveness. The Byzantine chalice that set these events in motion was eventually given to the Blisses, who became the greatest collectors of Byzantine art in modern times. It is on display in Dumbarton Oaks, formerly the Blisses’ house in Georgetown and now the leading center for research on the Byzantine world.

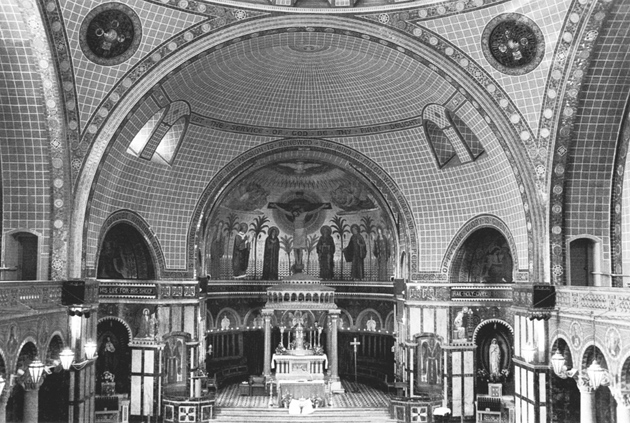

Such was the hold now of Byzantium over Western aesthetics that one Hagia Sophia was not enough, and many capital cities had to have one. London, New York, Paris, Washington, and Chicago all have copies of Hagia Sophia. They tend to be about half the size of the model, and reproduce features such as the great dome with a ring of windows at its base, and the large altar apse with smaller apses inside it. They are eclectically furnished and decorated, often in a Western medieval style. But that they are unmistakably copies can amaze visitors who have seen the original.

The dome mosaic of St. Sophia on Moscow Road in London, which Bullen puts on the cover of his book, is so authentically Byzantine in appearance that most people would assume it is a thousand years earlier than 1874. St. Sophia is a functioning Orthodox church, and a Sunday morning visit to Bayswater still affords the curious visitor the privilege of an interminable, incense-filled service under a Byzantine dome.

St. Anselm’s, at 685 Tinton Avenue in the South Bronx, on the other hand, was built to serve a Roman Catholic congregation. It is an offshoot of the Benedictine abbey of Beuron in south Germany, which was a center of medieval revival in the late nineteenth century. German missionaries planted the foundations of St. Anselm’s in 1892 in a Bronx that was far greener than it is now, and finished it in 1916–1917, when German immigration was already giving way to Irish, and then to Spanish. Protected today by an iron fence and multiple locks but open to visitors, this neo-Byzantine gem can be admired as one of the finest examples of the medieval revival in America.

Paris has a copy of Hagia Sophia in a far nicer neighborhood, Saint-Esprit, in the twelfth arrondissement, built by Paul Tournon in 1928–1935 with wall paintings by Maurice Denis and younger artists in what might be called a Catholic Symbolist style. Neither the style nor the surface of the raw concrete of which the church is built has worn well with time, but there is still a certain grandeur in this exact if smaller copy of the Great Church.

The largest of the copies, in fact the seventh-largest church in America, is Sts. Constantine and Helen in Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood. It was built in 1947–1966 by a Greek-American congregation. Then postwar white flight and black immigration to the South Shore (this is the neighborhood to which Michelle Obama’s family came from South Carolina) reduced the Greek community’s numbers drastically. The church was put up for sale in 1971 and bought by the Nation of Islam, which converted it to Muhammad’s Holy Temple. In 1988 it was sold to Louis Farrakhan and renamed Mosque Maryam. The cross over the dome was replaced by a crescent and star and Arabic verses were inscribed on the arches. For nonbelievers the mosque is now impossible to visit, like Hagia Sophia after the conquest.

Byzantium, so despised as a civilization by Gibbon and the Enlightenment, and Hagia Sophia, lost to the West seemingly forever after the Ottoman conquest, both proved their ultimate resilience. With the Byzantine revival brought into focus by these fine books, one can more readily see how a lost and reviled world served as a vital school for art and literature in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

This Issue

November 5, 2009

-

*

Sketches of the History of Christian Art (London: J. Murray, 1847), Vol. 1, p. 59. ↩