Published in 1935 in the middle of the Depression, William Empson’s Some Versions of Pastoral casts a hard modern light on sixteenth- and seventeenth-century poems about shepherds and shepherdesses with classical names like Corydon and Phyllida. Pastoral, Empson wrote, was a “puzzling form” and a “queer business” in which highly educated and well-heeled poets from the city idealized the lives of the poorest people in the land. It implied “a beautiful relation between the rich and poor” by making “simple people express strong feelings…in learned and fashionable language.” From 1935 onward, no one would read Spenser’s The Shepheardes Calendar or follow Shakespeare’s complicated double plots without being aware of the class tensions and ambiguities between the cultivated author and his low-born subjects.

Although shepherds and shepherdesses have been in short supply in the United States, versions of pastoral have flourished here. The cult of the Noble Red Man, or, as Mark Twain derisively labeled it, “The Fenimore Cooper Indian” (a type given to long speeches in mellifluous and extravagantly figurative English), is an obvious example. So is the heroizing of simple cowboys, farmers, and miners in the western stories of writers like Bret Harte, the movies of John Ford, and the art of Frederic Remington, Charles M. Russell, Maynard Dixon, and Thomas Hart Benton. Both Uncle Tom’s Cabin and The Grapes of Wrath might be read as pastorals in Empson’s sense. The chief loci of American pastoral have been the rural South and the Far West, while most of its practitioners have been sophisticated easterners for whom the South and West were destinations for bouts of adventurous travel. They went equipped with sketchpads and notebooks in which to record the picturesque manners and customs of their rustic, unlettered fellow countrymen.

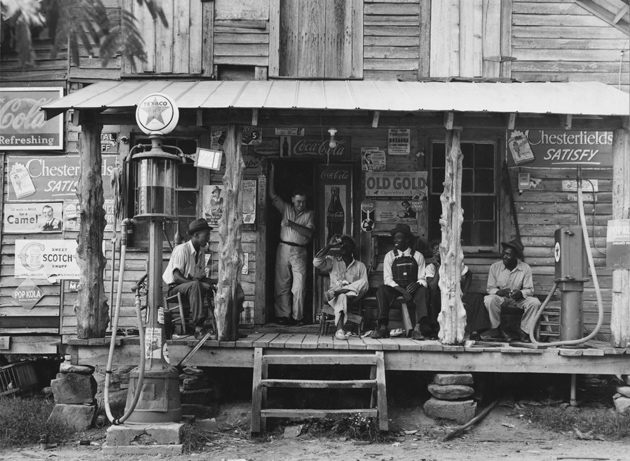

Empson noted the connection between traditional pastoral and Soviet propaganda, with its elevation of the worker to a “mythical cult-figure,” and something similar was going on during the New Deal when the Resettlement Administration (which later morphed into the Farm Security Administration) dispatched such figures from Manhattan’s Upper Bohemia as Walker Evans and Marion Post to photograph rural poverty in the southern states. Like a Tudor court poet contemplating a shepherd, the owner of the camera was rich beyond the dreams of the people in the viewfinder, whose images were used by the government both to justify its Keynesian economic policy and to raise private funds for the relief of dispossessed flood victims, sharecroppers, and migrant farm workers. Some, though not all, of the photographers were, like Evans, conscious artists; their federal patrons, like Roy Stryker, head of the information division of the FSA, were unabashed propagandists who judged each picture by its immediate affective power and took a severely practical approach to human tragedy.

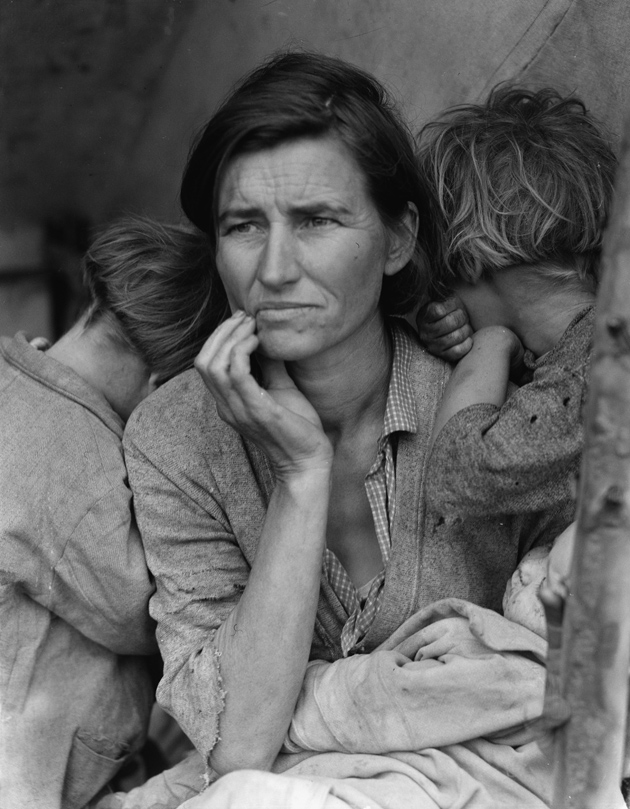

Of all the many thousands of photographs that came out of this government-sponsored enterprise, none was more instantly affecting or has remained more famous than Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother. Taken in February 1936 at a pea pickers’ camp near Nipomo, seventy miles northwest of Santa Barbara, it was published in the San Francisco News the following month, when it resulted in $200,000 in donations from appalled readers. In 1998, it became a 32¢ stamp in the Celebrate the Century series, with the caption “America Survives the Depression.” For a long while now, I’ve tried to observe a self-imposed veto on the overworked words “icon” and “iconic,” but in the exceptional case of Migrant Mother it’s sorely tempting to lift it.

The picture defines the form of pastoral as Empson meant it, and the closer one studies it, the more one’s made aware of just what a queer and puzzling business it is. A woman from the abyssal depths of the lower classes is plucked from obscurity by a female artist from the upper classes and endowed by her with extraordinary nobility and eloquence. It’s not the woman’s plight one sees at first so much as her arresting handsomeness: her prominent, rather patrician nose; her full lips, firmly set; the long and slender fingers of her right hand; the enigmatic depth of feeling in her eyes.

Even after many viewings, it takes several moments for the rest of the picture to sink in: the pervasive dirt, the clothing gone to shreds and holes, the seams and furrows of worry on the woman’s face and forehead, the skin eruptions around her lips and chin, the swaddled, filthy baby on her lap. As one can see from the other five pictures in the six-shot series, Lange posed two elder children, making them avert their faces from the camera and bury them in the shadows behind their mother, at once focusing our undistracted attention on her face and imprisoning her in her own maternity. It’s a portrait in which squalor and dignity are in fierce contention, but both one’s first and last impressions are of the woman’s resilience, pride, and damaged beauty.

Advertisement

Against all odds, she’s less a figure of pathos than of survival, as the inscription on the postage stamp accurately described her. In 1960, Lange said of the woman that she “seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it”—a nice instance of Empson’s “beautiful relation between the rich and poor”—which was not at all how her subject remembered the occasion.

In 1958 the hitherto nameless woman surfaced as Florence Thompson, author of an angry letter, written in amateur legalese, to the magazine U.S. Camera, which had recently republished Migrant Mother:

…It was called to My attention…request you Recall all the un-Sold Magazines…should the picture appear in Any magazine again I and my Three Daughters shall be Forced to Protect our rights…Remove the magazine from Circulation Without Due Permission…

Years later, Thompson’s grandson, Roger Sprague, who maintains a Web site called migrantgrandson.com, described what he believed to be her version of the encounter with Lange:

Then a shiny new car (it was only two years old) pulled into the entrance, stopped some twenty yards in front of Florence and a well-dressed woman got out with a large camera. She started taking Florence’s picture. With each picture the woman would step closer. Florence thought to herself, “Pay no mind. The woman thinks I’m quaint, and wants to take my picture.” The woman took the last picture not four feet away then spoke to Florence: “Hello, I’m Dorothea Lange, I work for the Farm Security Administration documenting the plight of the migrant worker. The photos will never be published, I promise.”

Some of these details ring false, and Sprague has his own interest in promoting a counternarrative, but the essence of the passage, with its insistence on the gulf of class and wealth between photographer and subject, sounds broadly right. “The woman thinks I’m quaint” might be the resentful observation of every goatherd, shepherd, and leech-gatherer faced with a well-heeled poet or documentarian on his or her turf.

It also emerged that Florence Thompson was not just a representative “Okie,” as Lange had thought, but a Cherokee Indian, born on an Oklahoma reservation. So, in retrospect, Migrant Mother can be read as intertwining two “mythical cult-figures”: that of the refugee sharecropper from the Dust Bowl (though Thompson had originally come to California with her first husband, a millworker, in 1924) and that of the Noble Red Man. There is a strikingly visible connection, however unnoticed by Lange, between her picture of Florence Thompson and Edward S. Curtis’s elaborately staged sepia portraits of dignified Native American women in tribal regalia in his extensive collection The North American Indian (1900–1930), perhaps the single most ambitious—and contentious—work of American pastoral ever created by a visual artist.

Both Linda Gordon’s Dorothea Lange and Anne Whiston Spirn’s Daring to Look hew to the line that Lange suddenly became a documentary photographer in 1932, when she stepped out of her portrait studio at 540 Sutter Street in San Francisco’s fashionable Union Square and took her Rolleiflex out onto the streets of the Mission District, three miles away, where she began to photograph men on the ever-lengthening breadlines in the last year of Hoover’s presidency. But this is to underplay the importance of the pictures she took from 1920 onward when she accompanied her first husband, Maynard Dixon, on his months-long painting trips to Arizona and New Mexico.

Lange was twenty-four when they married in March 1920, Dixon twenty years older. She was still a relative newcomer to San Francisco, having arrived there from New York in 1918; marrying Dixon, she also embraced his nostalgic and curmudgeonly vision of the Old West. A born westerner, from Fresno, California, he stubbornly portrayed the region as it had been before it was “ruined” by railroads, highways, cities, Hollywood, and tourism. In his paintings, the horse was still the primary means of power and transportation in a land of sunbleached rock and sand, enormous skies, cholla, and saguaro cacti, with adobe as its only architecture and Indians and cowboys its only rightful inhabitants. Although Lange had already established herself as an up-and-coming portrait photographer in San Francisco, her pictures on these trips to the desert were so faithful to her husband’s vision of the West that one might easily mistake many of them for Maynard Dixon paintings in black-and-white.

Advertisement

So she caught a group of Indian horsemen, seen from behind, riding close together across a sweep of empty tableland; a line of Hopi women and a boy, clad in traditional blankets, climbing a rough-hewn staircase trail through the pale rock of the mesa; a man teaching his son how to shoot a bow and arrow; families outside their adobe huts; and somber, unsmiling portraits of Indians whose faces show the same weary resignation to their fate as the faces that Lange would later photograph on the breadlines and in migrant labor camps. It was among the Hopi and the Navajo that she picked up the basic grammar of documentary, with its romantic alliance between the artist and the wretched of the earth.

One photograph stands out from her travels in the Southwest: a radically cropped print of the face of a Hopi man, in which much darkroom cookery clearly went into achieving Lange’s desired effect. At first sight, it looks like a grotesque ebony mask, its features splashed with silver as if by moonlight. Its skin is deeply creased, its eyes inscrutable black sockets. In its sculptural immobility, it appears as likely to be the face of a corpse as of a living being.

Seeing the finished picture, no one would guess the raw material from which Lange made the image as she focused her enlarger in the dark. There’s an uncropped photo of the same man, obviously shot within a minute or two of this one, to be seen in the Oakland Museum of California’s vast online archive of Lange’s work, in which he’s wearing a striped shirt and a bead necklace strung with Christian crosses, and has his hair tied with a knotted scarf around his forehead. His face looks humorous and easygoing; he seems amused to be having his picture taken.

This is not the negative that Lange used for her print, but it’s so close as to be very nearly identical. For the mask-like portrait, she moved her camera a few inches to her right, so that the razor-edged triangular shadow of the man’s nose exactly meets the cleft of his upper lip, and lowered it to make him loom above the viewer. What is remarkable is how she transformed the merry fellow in high sunshine into the unsettling and deathly face of the print. It might be titled The Last of His Race, or, as Edward S. Curtis called one of his best-known photographs, The Vanishing Race. There is, alas, no record of what the subject thought of his metamorphosis into a gaunt symbol of extinction.

Linda Gordon’s substantial, cradle-to-grave biography of Lange is usefully complemented by Anne Whiston Spirn’s careful documentation of one year—1939—in Lange’s working life. Both books have their flaws, but between them they add up to a satisfyingly binocular portrait of the photographer as she traveled the ambiguous and shifting frontier between art, journalism, social science, and propaganda. Lange’s work is much harder to place than that of, say, Walker Evans, and so is her personality. If neither Gordon nor Spirn quite succeeds in bringing her to life on the page, they do convey her complex and mercurial elusiveness. Roy Stryker of the FSA, who worked closely with Lange from 1935 through 1939, repeatedly sacking then rehiring her, vastly admired her photographs but found her maddening to deal with, and readers of Gordon and Spirn are likely to find themselves similarly conflicted.

Gordon, a social historian at NYU, whose faculty bio says that she specializes in “gender and family issues,” is best at placing her subject within the context of the various milieus in which she moved. She is good on the artistic and photographic scene in New York in the Teens of the last century, where the young Lange discovered Isadora Duncan, Alfred Stieglitz, and the luminaries of the Pleiades Club, and excellent on the rowdier bohemian coterie that she joined in San Francisco in the Twenties, where she met Dixon (in his customary urban uniform of Stetson and spurred cowboy boots), Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Frida Kahlo, and Diego Rivera. Gordon is reliably lucid on the aesthetic and political movements of the time, though Lange herself too often remains more cipher than character in an otherwise vivid picture of her place and period.

It’s in the gender and family issues department, her academic specialty, that Gordon is simultaneously confident and not entirely persuasive. Much is made of Lange’s childhood polio, which left her with a crippled right foot and permanent limp. Gordon calls her “a polio”—a grating phrase, which, according to Google, is rare but not without precedent. Further hurt was inflicted on Lange when her father moved out of the Hoboken house when she was twelve; and in writing of her as a wife and mother, prone to “hubris,” “irascibility,” “rages,” and “obsessive control,” Gordon portrays her as a damaged woman.

Lange acquired a stepdaughter, Consie, when she married Dixon, with whom she had two children of her own, Dan and John. In her second marriage, to the Berkeley economist Paul Taylor, she added three more stepchildren to her brood, in an age when women were expected to do all the work of parenting. Like so many people of their class and generation, the Dixons and the Taylors were in the habit of boarding out their kids whenever they threatened to interfere with their demanding work schedules. Not surprisingly, the children came to remember Lange as a domestic tyrant who neglected their needs and scarred them for life.

Autres temps, autres moeurs. Artists and writers were especially culpable in this regard, taking the line that their unique talents entitled them to days of concentrated silence and bibulous, grown-up, social evenings, undistracted by the barbaric yawps of the nursery. (Chief among Cyril Connolly’s Enemies of Promise was “the pram in the hall.”) Lange’s treatment of the children in her life was not egregiously different from that of others in her set in San Francisco and Taos, and Gordon’s nagging concern over her deficiencies as a parent tends to unbalance her book.

Although Gordon speculates freely about Lange’s thoughts and feelings, and surrounds her with an impressive mass of contingent details, one waits in vain to catch the pitch of her voice in conversation, her wit (did she have wit?), her personal demeanor and manners when at ease among friends. She emerges from the book more as a stack of interesting attributes than as a fully realized character in her own right.

Where Gordon’s Dorothea Lange and Spirn’s Daring to Look coincide to happiest effect is on Lange’s marriage to Paul Schuster Taylor and her on-again-off-again work for Stryker at the FSA. Taylor, described by Gordon as “a stiff and slightly ponderous suit-and-tie professor” (she’s often sharper on her secondary characters than she is on her primary one), met Lange in 1934, shortly after her separation from Maynard Dixon, at an exhibition of her pictures of the San Francisco poor at a gallery in Oakland. Later that year, he hired her, at a typist’s salary, as the official photographer for the California Division of Rural Rehabilitation, of which he’d just been appointed field director. From January 1935, they were traveling together across California, visiting enormous, featureless agribusiness farms, worked by mostly Mexican migrant laborers. Taylor, who’d learned Spanish for the purpose, conducted interviews while she took photos. She took to calling him Pablo, he called her mi chaparrito (“my little shorty”). They were married in December.

Much as she’d learned to see the uncultivated West through Maynard Dixon’s eyes, and to frame her pictures like Dixon paintings, in Taylor’s company she acquired the mental habits of a painstaking social anthropologist. Taylor taught economics at Berkeley, but his avidity for human data took him far outside the usual confines of his discipline and into the “field,” where he transcribed the life stories of migrants. Lange copied him. A shy man, Taylor would introduce himself to groups of Mexicans by saying that he was lost and needed directions, a technique quickly adopted as her own by Lange. Soon after they’d met, she began to accompany her photographs with what she called “captions”—crisply detailed accounts, some running to essay length, of the circumstances that had led each subject to his or her present situation.

For Stryker at the FSA, the picture was the thing, and he spiked all, or nearly all, of her writing; in Daring to Look, Spirn reunites Lange’s 1939 photos with their original texts in a long-overdue act of restoration. The captions are rich in themselves, full of the dollars and cents of anguished household accounting, stories of escape from starved-out Dustbowl farms in rattletrap Fords, and snatches of talk, for which Lange had a fine ear; as a North Carolina woman told her, “All the white folks think a heap of me. Mr. Blank wouldn’t think about killing hogs unless I was there to help. You ought to see me killing hogs at Mr. Blank’s!” She was a patient listener, and relentlessly inquisitive. Photographing tobacco farmers, for instance, she became expert on how the plant was cultivated, harvested, cured, and sold, and her captions describe with great precision what was meant by such terms as “topping,” “worming,” “sliding,” “priming,” “saving,” “putting in,” “yellowing,” “killing out.”

Gathering this sort of information from her subjects changed the way she photographed them. Before 1935 and her collaboration with Taylor, she was a fly-on-the-wall observer in her pictures of Native Americans and the unemployed. After 1935, her photographs reflect an increasingly intimate relationship between the woman behind the camera and the person in front of it. One sees a new candor and engagement in her subjects’ faces, as if each shutter-click has momentarily interrupted an absorbing conversation. In this respect, Migrant Mother is quite atypical of Lange’s FSA work: she spent only a few minutes with Florence Thompson, and her caption is unusually brief (according to Thompson’s grandson, it was also riddled with errors of fact).

The deepening involvement in her subjects’ lives seems all the more impressive when one follows the hectic itinerary of her own life in Daring to Look. Between January and October 1939 she traveled far and wide through the states of California, North Carolina, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, spending weeks at a time in her car, documenting the trudging “bindlestiffs” and homeless families on Highway 99, the labor camps and mile-wide fields of factory farms in the California valleys, tobacco in North Carolina, “stump farms” on logged-over forest in the Pacific Northwest, the newly irrigated orchards and farms of the Columbia basin. Wherever she went, she attached individual faces and stories to the desolate social geography of American agriculture from coast to coast. Spirn’s book is redolent of the hot and dusty unpaved roads on which Lange drove by day, and of inadequately lit rooms in cheap motels, where she wrote up her captions in the evenings.

Bad as her relations with Stryker were, she made her best pictures for the FSA. The current of indignant political feeling that flows through her work was in tune with the agency’s propagandist mission, and—more than Evans, Ben Shahn, Marion Post, and other FSA photographers—Lange had an increasingly deep knowledge and understanding of what she was seeing, as a result both of her own searching interviews with her subjects and of her husband’s work on the inequities of the agricultural economy.* Time and again, she struck a perfect balance between photographing a mass plight and honoring the dignity of each singular life—a balance she never quite recaptured again. Her 1942–1943 series on Japanese internment, for instance, has ample indignation, but lacks the active and visible rapport that she made with the farmworkers.

In 1954, Lange snagged a commission from Life magazine to do a photo-essay on Ireland, and around 2,500 negatives survive from this trip, which she made with her son Dan, then twenty-nine and an aspiring writer. Daniel Dixon was assigned the job of interviewing subjects and composing captions, leaving her free to concentrate entirely on photography. The results of this unwise division of labor are revealing.

In County Clare, Lange was an enchanted tourist. After the barbed wire and vast flat landscapes of Californian agribusiness, she reveled in the small, irregular, hillocky Irish fields, their rainwashed drystone walls and ancient hedges. Instead of improvised shack-towns and government-built camps, she focused on stone bothies overhung with thatch and streets of single-storey terraced cottages with rickety horse-drawn traps parked at their doors. She stopped to take shots of ruined churches; placid, grazing cows; horses and haywains; old men with scythes; shepherds tending their flocks in the fields and driving them down narrow lanes. In Lange’s Ireland, almost everybody’s smiling, and her photographs form an archive of 1950s toothless, gap-toothed, and prosthetic Irish grins. Yet there’s little hint of two-way rapport in the faces of these people, who appear to be saying “Cheese” to deferentially oblige the lady-visitor from America, as she roamed the countryside picturing its happy peasantry.

She hardly seemed to notice that the clothes of her Irish subjects were as tattered and patched as those of the poorest Okies. If she questioned why the farms and fields were so small, or why there were so many horses and so few machines, it doesn’t show in her photographs. She was here to discover Arcadia—a land of simple folk, content with their lot, going about their time-hallowed rustic occupations, equipped with the same rudimentary technology that had served them for centuries. In Ireland, Lange reverted to pastoral in its most naive and sentimental form. It’s tantalizing to wonder how she would have handled this assignment had the commission come from a social activist like Stryker instead of Henry Luce’s Life. Her photos were in perfect harmony with the conservative politics of the magazine: they extol the tranquillity of a society under the law of Nature, and of God.

The magazine savagely cut Lange’s essay, rejected Daniel Dixon’s captions, and supplied its own, including “serenely they live in age old patterns” and “THE QUIET LIFE RICH IN FAITH AND A BIT OF FUN.”

In the last chapter of Daring to Look, Anne Whiston Spirn drives along the routes taken by Lange in 1939. By 2005 the roads were generally improved but the housing and social conditions of agricultural workers on industrial farms were little changed, and Spirn found new rural slums on the sites of the old New Deal labor camps. A caption written by Lange in 1939 still holds broadly true:

The richer the district in agricultural production, the more it has drawn the distressed who build its shacktowns. From the Salt River valley of Arizona to the Yakima valley of Washington, the richest valleys are dotted with the biggest slums.

This is painfully evident in Washington state, where I live. Were Lange to return here with her camera seventy years on, it would not be a Rip Van Winkle experience so much as a numbing sense of déjà vu. The cities and suburbs would be unrecognizable to her, but the poverty in the countryside created by the corporate agricultural system would yield material for photographs identical to those she took in 1939. There are small, Spanish-speaking farm towns on the Columbia plateau where the average per capita income is still in the middling four figures.

In summer, migrant fruit pickers pile into the Columbia and Yakima valleys, living in camps little different, and hardly more affluent, than the one where Lange found Florence Thompson. And inventive new ways of being poor continue to emerge. In Forks, at the foot of the Olympic National Park, there are run-down trailer parks on the edges of the town, inhabited by “brushpickers,” mostly Guatemalan, who make a tenuous living by scavenging in the woods for the moss, ferns, beargrass, and salal used by florists around the world to add greenery to bouquets.

Migrant Mother has become the symbol of a now-remote decade, to which the passage of years has lent a period glow. Yet across the rural West the Great Depression is less a historical event than a permanent condition, which existed before the 1930s and is still there now, though it shifts from place to place and fluctuates in its severity. The warning in the rearview mirror applies here: the lives in Lange’s photographs for the FSA are closer than they may appear.

This Issue

November 19, 2009

-

*

Taylor and Lange merged their talents in An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion, published in 1939. The couple assembled her photographs, his text, and their captions, working together, as they wrote, “in every aspect of the form as a whole to the least detail of arrangement or phrase.” ↩