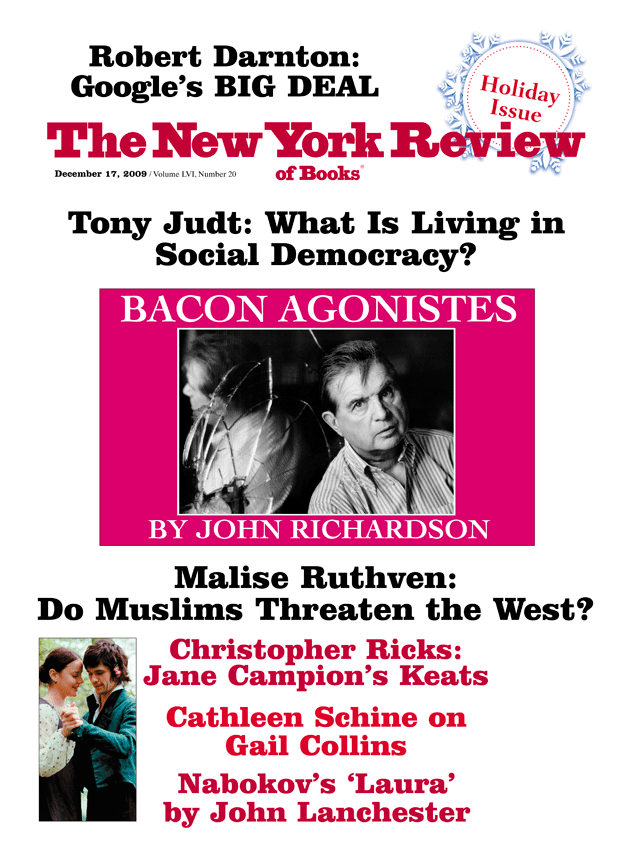

The Jane Campion film Bright Star, about the love that John Keats and Fanny Brawne had for one another (more particularly about the love that she had for him), does indeed exercise its imagination. Yet it does not truly exercise ours. 1

This is because the film is mistaken to the point of perversity about the nature of imagination when it comes to a poet and especially to this poet. That a film cannot but show us pictures is admittedly the essence of the medium, and in the old days it was to the pictures that we used to go. (In 1915 the Kinematograph & Lantern Weekly still called upon quotation marks when speaking of a very successful career in “pictures.”) But it is imperative that the pictures within such a film as Bright Star practice one simple unremitting act of self-abnegation: of never being pictures of the very things that a great writer has superbly—by means of the chosen medium of words alone—enabled us to imagine, to picture. A film that proceeds to furnish competing pictures of its own will render pointless the previous acts of imagination that it purports to respect or to honor. For among the accomplishments of the poet is that he or she brings it about that we see with the mind’s eye, as against the eye of flesh. The sense of the word “picture” as “a visible image of something formed by physical means” is the antithesis of the sense as “a graphic description, written or spoken, capable of suggesting a mental image.”

Much of the genius of Keats lies in description that is graphic despite—as well as because of—its not existing in any of the media that constitute the graphic arts. In Keats’s art (his letters quite as much as his poems), even the word “description” falls short of his astonishing achievement, in that his imagination never limits itself to describing; rather, thanks to a whole range of corporeal imaginings, it realizes. For it imagines not only seeing (when all that we are physically seeing is words on a page) but the creative power of empathy and of sympathy by means of all the senses. Keats’s words are so telling as to need no showing of what they conjure up. Not merely do they not need such showing, they need not to be accorded it. This winding around is in line with “In Drear-Nighted December” when it speaks of “the feel of not to feel it.”

Jane Campion has spoken of “the lamp lit by his poetic genius”: “It is Bright Star ‘s ambition to sensitize the audience, to light the lamp.” But the verb “to sensitize” is distant from sensibility and sensitivity, and had we not just been told that it was Keats’s poetic genius that lit the lamp? In The Seven Lamps of Architecture, Ruskin illuminated “The Lamp of Truth” because he valued not only truth but imagination, or (more exactly) valued the symbiotic relations between truth and imagination:

It might be at first thought that the whole kingdom of imagination was one of deception also. Not so: the action of the imagination is a voluntary summoning of the conceptions of things absent or impossible; and the pleasure and nobility of the imagination partly consist in its knowledge and contemplation of them as such, i.e. in the knowledge of their actual absence or impossibility at the moment of their apparent presence or reality…. It is necessary to our rank as spiritual creatures, that we should be able to invent and to behold what is not; and to our rank as moral creatures, that we should know and confess at the same time that it is not.

Ruskin himself commands the pleasure and nobility that he salutes. For the imagination acknowledges both the power and the poignancy of It is as if… The Lamp of Truth had shone upon and from Leigh Hunt, too, when he praised a moment in early Keats as “a fancy founded, as all beautiful fancies are, on a strong sense of what really exists or occurs.”

Keats’s sonnet “Bright star! would I were steadfast as thou art” was transcribed by Fanny Brawne in the copy of Cary’s translation of Dante that Keats had given her. This gives us grounds for trusting that “Bright star!” is about her (not, manifestly, to her in one sense of “to,” since “thou” is the star, and the poem speaks of “her”). In the matter of how the film chooses to deploy the sonnet and other snatches of poems, the question is whether Campion’s imagination mines Keats’s art or undermines it:

Bright star! would I were steadfast as thou art—

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priest like task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors—

No—yet still steadfast, still unchangeable,

Pillowed upon my fair love’s ripening breast,

To feel for ever its soft swell and fall,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever—or else swoon to death.

The sonnet comes to picture a star that watches and that gazes, and then it moves to imagining, not what it is to see and to be seen, but what it is to touch and to hear, to touch a breast, to hear a breath. Exquisitely imagined. The young couple in the film are not, at this point, to be grudged their pleasure in being together bodily and lovingly, and the scene does not lapse into the torrid. But to insist that the entwined lovers be accompanied by lines from the sonnet is to reduce the poem from a dramatic imagining to a stage direction or even a gloss. Keats utters the words “Pillowed upon my fair love’s ripening breast,” and his head has to be duly pillowed, or at any rate cushioned, on her breast.

Advertisement

At the very end of the film, Fanny recites “Bright star!” Since the poem speaks of snow, there not only has to be snow on the ground but Fanny has to glance in its direction. When Keats, away from Fanny, evokes in a letter the setting where he is, at a window in sight of the sea, there has to be a sight of the sea, and then of him standing by the sighted sea. Moreover, to have him say to her in the film those things that he set down in letters to her (or, since this liberty is taken, in letters to others) is to misrepresent the nature of a letter and of a conversation, his conduct, and their relationship. When what he writes in a letter finds itself staged explicitly as a “poetry class” (a tutorial, indeed) for Fanny, there is an infidelity to his manners, his voice, his humor, and his art not only as a poet but as one of the very greatest of letter-writers. “If Poetry comes not as naturally as the Leaves to a tree it had better not come at all” 2 : it was one thing for him to write this to his friend John Taylor (February 27, 1818), it is another for him to trot it out priggishly at Fanny in Campion’s film. Elsewhere, voice-over is overused, as though none of us would have the patience to read for ourselves a few sentences from a letter that is before our eyes.

Keats is an imaginer of all the senses, and our gratitude to him is for his giving us not the experience of the senses, but the experience of imagining the senses, the experience of finding imagined in words what at the same time we know to have an existence other than in words. This, not as ineffability, but as imagination that has its own well-grounded truth. “The Imagination may be compared to Adam’s dream—he awoke and found it truth” (Keats to Benjamin Bailey, November 22, 1817).

The unwisdom of putting pictures to his words, the result being that there is no longer any picturing to be done, might be brought home if one were to consider how preposterous it would be to eke out Keats’s words with a sensory “input” from any of the other senses.

Sideway his face repos’d

On one white arm, and tenderly unclos’d,

By tenderest pressure, a faint damask mouth

To slumbery pout; just as the morning south

Disparts a dew-lipp’d rose.(Endymion, II. 403–407)

How about pinioning the reader of these lines and installing him or her in a “virtual” pressure-cabin so as to feel the real thing, instead of having to make do with Keats’s shot at imagining in words a tenderest pressure? But Keats’s imagination is a real thing, and to aid it, not aesthetically but prosthetically, would be positively—that is, negatively, to the point of negatingly—misguided. The sense of touch is to be imagined by the reader, by courtesy of Keats’s imagining it, and any actual touching would be, as they say, “inappropriate.” Again, the provision of “virtual” body warmth would not be a way of giving body to, or fleshing out, Keats’s bodily imagining of a bodice and more, but a sure way to eviscerate it. Porphyro, in hiding, imagines away:

Anon his heart revives: her vespers done,

Of all its wreathèd pearls her hair she frees;

Unclasps her warmèd jewels one by one;

Loosens her fragrant boddice; by degrees

Her rich attire creeps rustling to her knees….(“The Eve of St. Agnes,” xxvi)

How about supplying first of all a perfume (“fragrant,” remember) and then a sound effect (“rustling,” don’t forget), so as to make sure that we get the picture, and smell and hear it? Or there could be the assistance that could be given to our imagining a taste, a mouth:

Advertisement

and here, undimm’d

By any touch, a bunch of blooming plums

Ready to melt between an infant’s gums….(Endymion, II. 449–451)

The laboratory world of our day would probably be able to introduce us to an actual physical sensation of the infant gums, and for the mature palate there could no doubt be found a sensation that would enforce (albeit while annulling) some other famous lines:

She dwells with Beauty—Beauty that must die;

And Joy, whose hand is ever at his lips

Bidding adieu; and aching Pleasure nigh,

Turning to poison while the bee-mouth sips:

Ay, in the very temple of Delight

Veiled Melancholy has her sovran shrine,

Though seen of none save him whose strenuous tongue

Can burst Joy’s grape against his palate fine;

His soul shall taste the sadness of her might,

And be among her cloudy trophies hung.(“Ode on Melancholy,” 21–30)

And lest there be any sentimentalizing of what a taste in the mouth can be, provision could always be made for us to undergo something very different from Joy’s grape:

Instead of sweets, his ample palate took

Savour of poisonous brass and metal sick….(Hyperion, 188–189)

“Talking of Pleasure, this moment I was writing with one hand, and with the other holding to my Mouth a Nectarine—Good God how fine. It went down soft pulpy, slushy, oozy—all its delicious embonpoint melted down my throat like a large beatified Strawberry. I shall certainly breed” (Keats to Charles Dilke, September 22, 1819). The very words breed, they do it, and they would be undone by any helping of them out. Leigh Hunt is at his best in sensing this:

Here is delicate modulation and super-refined epicurean nicety! “Lucent syrups, tinct with cinnamon,” make us read the line delicately, and at the tip-end, as it were, of one’s tongue.

The words are the feat, and any physical gustatory supplementing of them would be a fatuity.

Why not assist the “Ode to a Nightingale” by means of a recording of birdsong and of its full-throated ease? Would this not ease our appreciation? (The film promptly obliges.) But what is it that would distinguish this fatuous supplementation by means of the senses of taste, of touch, of smell, of hearing, from supplementation that calls upon the sense of sight? Is it simply that the sense of sight is more accommodating, more easily supplied?

My having recently to think again about Tennyson and the visual arts brought home to me some asymmetries that attend upon visualizing. It was to William Allingham that Tennyson uttered the crucial nineteenth-century word:

“As to visualising,” he said, “I often see the most magnificent landscapes.”

“In dreams?”

“Yes, and on closing my eyes. To-day when I lay down I saw a line of huge wonderful cliffs rising out of a great sweep of forest—finer than anything in nature.”

Other gifts he has, but T. is especially and pre-eminently a landscape-painter in words, a colourist, rich, full and subtle.

On closing my eyes : it was left to Samuel Beckett to focus this insight in a way that is both revelatory and comical. “If she closed her eyes she might see something” (More Pricks Than Kicks). “He closed his eyes the better to see what was still in spite of all a little dear to him” (Mercier and Camier). “In the days when Murphy was concerned with seeing Miss Counihan, he had had to close his eyes to do so” (Murphy). Or in the traditional terms of Andrew Marvell and “A Dialogue between the Soul and Body,” it may be that we are all incapable of seeing because of the eye, incapable of hearing because of the ear:

SOUL

O, who shall from this dungeon raise

A soul, enslaved so many ways,

With bolts of bones, that fettered stands

In feet, and manacled in hands.

Here blinded with an eye; and there

Deaf with the drumming of an ear….

To visualize is not the same as to see; more, it is incompatible with seeing. It is to form a mental picture of something not visible, perhaps not present, perhaps even not possible. There isn’t a counterpart to the word “visualize” for any of the other senses, for hearing or touching or tasting or smelling. Though we can perfectly well imagine hearing something, touching something, tasting something, or smelling something, we don’t have a word for doing so: we don’t audibilize, tactilize, gustatize, or olfactorize, any more than we have a counterpart in the other senses for what it is to picture something.

So here we have a tantalizing reminder of the uniqueness of sight, and of the fact that, as the great writers and thinkers have always known, it is sight, in all its majesty and power, that most threatens to tyrannize over the other senses, even as the senses are among the forces that threaten to tyrannize over us all. The imagination will help us, but it has already thrown itself behind one of the senses in particular, given that the supremacy of an image is apparently conceded every time we speak of imagination. Fortunately, to recognize the distinct and distinctive triumph that is visualizing may be one form of protection for the other senses against the triumphalism of sight. Though there is clearly no call to believe that to visualize is more valuable than to see, they are of different comfort and aid, and there can never be a substitute for such imagination as offers so much to the mind’s eye.

The notes that Keats made in his copy of Paradise Lost show his imagination fired by Milton’s imagination. “What creates the intense pleasure of not knowing? A sense of independence, of power, from the fancy’s creating a world of its own by the sense of probabilities.” Again: “A Poet can seldom have justice done to his imagination.” But there are particular reasons why the art of the poet can seldom have justice done to its imagination within the very different art (which is also the very medium) of film. For Keats, as he tries to imagine Milton imagining, it is the preposition “into” that may help him out: “One of the most mysterious of semi-speculations is, one would suppose, that of one Mind’s imagining into another.” Jane Campion’s mind sought to imagine into another, and yet it did not really put its mind to imagining, leave alone imagining into, the mind’s eye.

She has said that Keats’s poetry needs to be made “accessible”: “A lot of people feel alienated from poetry because they feel that they don’t understand it. But Keats is a great explainer of poetry and I wanted to use that in the story.” Yet Keats himself was wary of explanation, and what he regretfully said about Leigh Hunt would have some application to Jane Campion:

He understands many a beautiful thing; but then, instead of giving other minds credit for the same degree of perception as he himself professes—he begins an explanation in such a curious manner that our taste and self-love is offended continually. Hunt does one harm by making fine things petty and beautiful things hateful. Through him I am indifferent to Mozart, I care not for white Busts—and many a glorious thing when associated with him becomes a nothing.

Bright Star respects Fanny Brawne, and here the film gives us credit for the same degree of perception as the filmmaker, which is one reason why Abbie Cornish is moved to act very well and to achieve her feat of one mind (and one body) imagining into another. But the film does not respect John Keats, in that it does not respect his writing. When the profound words of the letters are presented as conversation, they sound staged, a lecture, and when the poems are gratuitously assisted, we hear not “the true voice of feeling,” but an actorly recitation at a PowerPoint presentation.

What is at issue is not the rights and wrongs of interpretation; we cannot do without interpretations, even while we know that when they are misguided they can come between us and a work of art. But there is a crucial difference between on the one hand, say, a poet’s reading aloud his or her work (or indeed anyone’s doing so, come to that) in order to bring out what the words have been concerned to bring in, and on the other hand, the condescending granting of pictorial assistance to words that were designed to stand in no need of support from a sister art.

One reviewer found it an authentic tribute to Keats that we do hear the whole of the “Ode to a Nightingale” while the final credits roll. But Keats’s words, made subservient not only to other words but to music and even to a heavenly choir, are ruthlessly overwhelmed by the credits that roll downward and onward at a speed and with a rhythm quite other than those of the poem, a poem that does, after all, deserve some of the credit.

This Issue

December 17, 2009

-

1

The Keats-Shelley Association of America had a panel discussion in which I took part (subsequently podcast) on Bright Star at the New York Coleman Center on September 13, 2009, to follow a showing of the film; Stuart Curran, the association’s president, presided, with Susan J. Wolfson and Tim Corrigan also forming the panel. ↩

-

2

Many of the letters and poems adduced here are reproduced in facsimile in Stephen Hebron’s handsome compilation, John Keats: A Poet and His Manuscripts (British Library, 2009). ↩