Although Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, is less than an hour’s drive from San Francisco, it sits alone in the landscape. The sense of ordered opulence on the campus is light-years away from the untidy, chaotic openness of the city on the bay. Of all the ghosts who wander Stanford’s halls, one of the most stern and powerful is that of the poet and critic Yvor Winters, an advocate of order and, indeed, of standing alone in the landscape. Winters was involved with the life of Stanford for almost forty years.

In 1954, soon after Thom Gunn’s first book, Fighting Terms, appeared, Winters wrote a wonderful letter to him. Aged twenty-six, Gunn was coming from England to study with him. Winters began by inviting the young poet to his house for supper as soon as he had located his lodgings in Palo Alto. “My most intimate friends are Airedales,” he wrote, “but I enjoy my poets, and during the school year I have not the time to see as much of them off the campus as I would like.”

Winters was disappointed that Gunn would see the Atlantic seaboard of the United States before he would see the West. “It is a dismal province,” he wrote,

and you will like the west the better, I suppose, for having seen the worst the first…. In California the earth is red on the western slope of the Sierras, and when you get down into the great valley, the grass will be dead and the air will be yellow. I find that I cannot endure to be far from the yellow air for very long. It is like gold to airy thinness beat, but it smells better.

Winters was right. Gunn would like the West; despite a few short absences, he was to remain in the Bay Area for the next fifty years until his death in 2004. Most of his half-century in the paradise that Winters described would be spent, however, not at Stanford where the air was yellow, but in San Francisco where the air was electric. The city’s street life and changing culture would become one of Gunn’s great subjects.

At first, however, Gunn had to be careful. In an interview he did with James Campbell, he explained that, while he had indeed come to California to study with Yvor Winters, he had left England “primarily to be in the same country as Mike [Kitay],” an American whom he had met in Cambridge, England, and with whom he spent the rest of his life. In his interview with Campbell, Gunn explained why, in his early love poems to Mike Kitay, he used “you” rather than “he” to disguise the gender of the loved one:

This was what Auden had always done. People say, “Why didn’t you come out of the closet, publicly, sooner than you did?” I would never have got to America, for one thing. I would never have got a teaching job, for another thing. And I would probably not have had openly homosexual poems published in magazines or books at that time, in 1954.

In his poem “To Yvor Winters, 1955,” Gunn not only made clear his gratitude to his first American mentor, but also displayed his own command of formal eloquence and precise statement:

You keep both Rule and Energy in view,

Much power in each, most in the balanced two:

Ferocity existing in the fence

Built by an exercised intelligence.

Though night is always close, complete negation

Ready to drop on wisdom and emotion,

Night from the air or the carnivorous breath,

Still it is right to know the force of death,

And, as you do, persistent, tough in will,

Raise from the excellent the better still.

It is easy to imagine how certain poets living not very far away would have greeted this poem in 1955, the same year as the famous Six Gallery Reading in San Francisco, introduced by Kenneth Rexroth; at this reading Allen Ginsberg first presented his poem “Howl”; Gary Snyder also took part; Lawrence Ferlinghetti was in the audience. These poets were not notable for their interest in the balance between rule and energy, or indeed their support for contemporary poems written in rhyming couplets. At the beginning Gunn’s “outraged sense of decorum” prevented him from making contact with these local poets, but when he did, it made a considerable difference to him, as did his reading of other poets such as William Carlos Williams and Robert Duncan.

Indeed, in the early 1960s Duncan came to replace Winters as Gunn’s closest mentor. Gunn wrote three essays about Duncan and dedicated a number of poems to him. The first essay opened with an account of a pioneering article by Duncan, published by Dwight Macdonald in the journal Politics in 1944, called “The Homosexual in Society,” in which Duncan had identified himself as homosexual. As a result of the article, John Crowe Ransom, who had enthusiastically accepted a long poem by Duncan for publication in The Kenyon Review, now refused to publish it. In an essay in At the Barriers: On the Poetry of Thom Gunn, Brian Teare quotes from Ransom’s letter to Duncan:

Advertisement

I cannot agree with you that we should publish it nevertheless under the name of freedom of speech; because I cannot agree with your position that homosexuality is not abnormal. It is biologically abnormal in the most obvious sense. I am not sure whether or not state or federal law regard it so, but I think they do…. There are certainly laws prohibiting incest and polygamy, with which I concur, though they are only abnormal conventionally and are not so damaging to society biologically.

Gunn’s friendship with poets such as Duncan in San Francisco and his adaptation to life on the west coast of America changed his style as a poet, allowed him to combine a poetic style that had taken its bearing from an intense study of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century forms with a looser system that could experiment in syllabics, free verse, and improvised structures. He was reading new and experimental American poetry with real seriousness and enthusiasm, a poetry that has still, to this day, not been easily embraced in England.

In his writing about the work of Duncan, Snyder, Ginsberg, and Robert Creeley, Gunn used phrases and terms such as “embodies the one really influential new theory of poetry advanced in our lifetime” (Duncan), “moral discipline…cleanness, exactness” (Snyder), “a career I find more exemplary with each succeeding year” (Ginsberg), and “command” (Creeley). It is easy to imagine the response not only of Yvor Winters, who had a low opinion of these poets when he did not view them with horror, as he indeed took a dim view of developments in Gunn’s own poems written after about 1960, but also easy to imagine the response of figures in England such as Philip Larkin whose view of the baleful influence of abroad was not likely to have been tempered by Gunn’s essays or by the changes apparent in his practice as a poet as early as 1961 when his third volume, My Sad Captains, appeared.1

In At the Barriers, there are two essays by Irish poets that evoke the excitement of finding Gunn’s poems for the first time. Eavan Boland describes hearing the poems read out loud by the poet Derek Mahon in 1964 when she was a student at Trinity College Dublin:

Gunn I had never heard of—neither his name nor his poems. I listened and listened. It all sounded strange to me—those blunt and thumping stanzas about cold roads and dance halls. And yet something about it was also familiar, startling, and thrilling. I was surprised, engaged and lost.

The poetry in these first books, Boland goes on,

metrically…makes a continuum with British poetry and looks to the past. But tonally it looks to a wide, improvised horizon, a future where irony and sexual dissidence would become a lens into a new poetic persona and a different configuration of modernism…. The music—metered and insistent—is definitely heavy metal.

Paul Muldoon describes reading Gunn’s poem “Considering the Snail” for the first time in 1967 when “much of [its] impact…would have been construable even to the sixteen-year-old boy I then was.” The poem appeared first in the second half of Gunn’s My Sad Captains and, instead of an iambic line, used a syllabic system, with seven syllables per line, letting the stress fall or not fall where it might:

The snail pushes through a green

night, for the grass is heavy

with water and meets over

the bright path he makes, where rain

has darkened the earth’s dark. He

moves in a wood of desire,pale antlers barely stirring

as he hunts. I cannot tell

what power is at work, drenched there

with purpose, knowing nothing.

What is a snail’s fury? All

I think is that if laterI parted the blades above

the tunnel and saw the thin

train of broken white across

litter, I would never have

imagined the slow passion

to that deliberate progress.

Muldoon manages in At the Barriers an ingenious reading of the poem’s intricacies and sources, its echoes and resonances, both clear and subtle, with other poems such as Milton’s “On His Blindness,” Earle Birney’s “Slug in Woods,” and Geoffrey Hill’s “Merlin,” and, indeed, with other poems by Gunn himself.

These accounts of reading Gunn for the first time in the 1960s and 1970s will have echoes and resonances for many of us. While the poems seemed steeped in the beauty of the cadences of Shakespeare and Marlowe, it was not that Gunn had merely mastered their style, stanza forms, and rhyme schemes. There was something else going on in his poetic diction. There was a deep sense of sexuality, sensuousness, and risk about the content of some of the poems; Gunn seemed also, in the very way he made his phrases and determined the beats and the rhymes, to be fondling language, playing with it as a lover might play. His poem “High Fidelity” began:

Advertisement

I play your furies back to me at night,

The needle dances in the grooves they made,

For fury is passion like love, and fury’s bite,

These grooves, no sooner than a love mark fade….

Also, there was something cheeky about him, a refusal to be dull or platitudinous about love. A stanza in “Modes of Pleasure (#2),” for example, read:

Yet when I’ve had you once or twice

I may not want you any more:

A single night is plenty for

Every magnanimous device.

He also had no respect for his elders. His poem “Lines for a Book” riffed on two poems by Stephen Spender (“I think continually of those who were truly great” and “My parents kept me from children who were rough”):

I think of all the toughs through history

And thank heaven they lived, continually.

I praise the overdogs from Alexander

To those who would not play with Stephen Spender.

More than his cheek, I loved Gunn’s insistence on the body itself as the source of energy that equaled that of the will—a word he used with unusual frequency; he allowed the possibility that instinct and appetite could measure up to intelligence. He seemed interested in movement, violence, and the lure of flesh. Even now, I love how an early poem such as “Tamer and Hawk” is filled with a mixture of sexual desire and lovely, ambiguous menace. Its opening stanzas read:

I thought I was so tough,

But gentled at your hands,

Cannot be quick enough

To fly for you and show

That when I go I go

At your commands.Even in flight above

I am no longer free:

You seeled me with your love,

I am blind to other birds—

The habit of your words

Has hooded me.

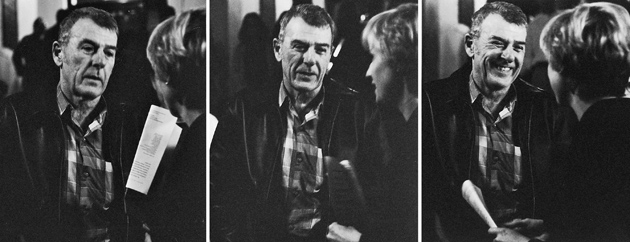

Like the hawk in his poem, Gunn as a poet is notoriously difficult to pin down. He was, as August Kleinzahler says, “an Elizabethan poet in modern dress.” He was an Englishman in California, but an Englishman replete with sexual glamour who, despite a thrilling honesty in some of the poems, did not deal in self-deprecation. He was rather proud of being alone among poets in dedicating poems to both Yvor Winters and Robert Duncan.

Thus in these decades when artists do not seem complete unless they have a double identity, Gunn seems ready to be interpreted for his doubleness and his reputation is likely to grow accordingly. He was a gay poet who wrote first in code and then openly. But his openness also comes doubled: he had a capacity, in a confessional age, to leave the self out of his work. Indeed, the avoidance of self is one of the hallmarks of his work and seems to have nourished his work. There was something tough and self-contained in his poetic personality but open too in certain ways and tender and generous. He could be easygoing and tolerant as a critic, but also fierce at times and almost bad-tempered.

This doubleness made its way into the very body of his work. He was interested as a poet in what was particular, exact, and clearly seen, but also in what was numinous, mysterious, and shimmering. He loved, for example, the liminal space between waking and sleeping or between nightmares and sweet, often drug-induced, dreams, and between sharp edges and flickering lines. He managed a hushed, baffled tone that made its way into poems of pure, almost sure statement and definition, but there were other poems where he seemed less certain and allowed for endings that, even if accompanied by clanging and direct rhymes, seemed open-ended and mysterious, but in a way that was hard-won and seldom vague.

Thus he could be read in Ireland and Britain in the 1960s and 1970s and seem shocking, thrilling; and then later, in the United States, he could be read again and his work could satisfy certain, and maybe easy, critical expectations, which arose from his very doubleness, or from the predatory sexual energy in some poems, or the view that he was a scholar in a leather jacket. As some of the essays in At the Barriers make clear, however, there are a number of single poems by Gunn that manage to soar above all of this, that have about them a slippery beauty, a level of poetic intelligence, which sets them beyond the initial shock of reading them, and beyond any debate about the author’s sexuality or his nationality or his doubleness. These poems include “The Wound” from his first book, Fighting Terms ; “In Santa Maria del Popolo” and “Considering the Snail” from his third book, My Sad Captains ; “Touch,” the title poem of his fourth collection; and “At the Centre” from his fifth collection, Moly, which was published in 1971.

These five poems are not written in a single style, or indeed in a single tone. Three of them use stanzas, strict meter, and rhyme, two a looser form. A note at the end of “At the Centre” says: LSD, FolsomStreet ; the poem is about an acid trip in San Francisco. Oddly enough, it is no worse for that, partly because of the tightness of its structure, but also because of its genuine sense of drugged experience, a puzzled and questing wonderment moving toward the possibility of knowledge beyond its reach:

What place is this

And what is it that broods

Barely beyond its own creation’s course,

And not abstracted from it, not the Word,

But overlapping like the wet low clouds

The rivering images—their unstopped source,

Its roar unheard from being always heard.

Gunn’s two collections of essays and reviews, The Occasions of Poetry and Shelf Life, display the range of his interests, his seriousness, his care as a reader, and his studiousness; they throw considerable light on his own practice as a poet. He also produced an edition of the selected poems of three poets who mattered enormously to him as a reader and as a poet: Fulke Greville (whose work Yvor Winters would also champion), Ben Jonson, and Ezra Pound. Greville, who was born in 1554, was a courtier during the reigns of Elizabeth I, James I, and Charles I. He was a close friend of Sir Philip Sidney. In describing the tradition that Greville and Sidney inherited, Gunn could easily be writing about his own early work:

Characteristically it is based on statement…. At its best, it has a compactness…in which the movement is emphatic without becoming deadening; and the straightforwardness of language and device is the very medium through which energy of thought and feeling emerges.

Greville’s reputation is based on “Caelica,” a sequence of more than a hundred poems begun around 1577 and finished by 1600. It may seem, especially from some poems at the end of the sequence, that the poems are exercises in Calvinist religious certainty, and thus it is surprising that Gunn took such an interest in them. But it is not merely their plain statement, their technical skill, and their use of convention that pulled Gunn toward them. It is also a sort of sensuality in Greville’s way of thinking, a sense of carefully worked-out truth in his tone, and at times a pure brilliance in how he manipulated rhythm or individual phrases.

In his introduction, Gunn emerges as a talented and rigorous close reader. He quotes in full what is one of Greville’s finest single poems, placed toward the end of the “Caelica” sequence:

In night when colours all to black are cast,

Distinction lost, or gone down with the light;

The eye a watch to inward senses plac’d,

Not seeing, yet still having power of sight,Gives vain alarums to the inward sense,

Where fear stirr’d up with witty tyranny,

Confounds all powers, and thorough self-offence,

Doth forge and raise impossibility:Such as in thick depriving darknesses,

Proper reflection of the error be,

And images of self-confusednesses,

Which hurt imaginations only see;

And from this nothing seen, tells news of devils,

Which but expressions be of inward evils.

Gunn insists on allowing the full weight of Greville’s religious feeling to outweigh a more modern, psychological, simple way of reading the poem. “Superficially,” he writes,

it seems a thoroughly rationalist poem explaining delusion in an almost Freudian way as the result of “hurt imagination” and “inward evils,” as repression emerging in dream or hallucination, but the whole emphasis of the poem…is on the real Hell, of which the night is simply image, and on the authority, that of God, of which one is deprived.

There are moments throughout Gunn’s essays when he, with full knowledge perhaps, describes a poet in terms that might equally be used to describe his own poetry. “And one of the marks of Greville’s love poems,” he writes, “is the penetration and accuracy with which they describe the perversity of human emotions.”2

His quote from Greville’s “Life of Sidney” displays something of the choices he himself faced as a poet in San Francisco in the early 1960s:

I found my creeping genius more fixed upon the images of life, than the images of wit, and therefore chose not to write to them on whose foot the black ox had not already trod, as the proverb is, but to those only, that are weatherbeaten in the sea of this world, such as having lost the sight of their gardens and groves, study to sail on a right course among rocks and quicksands.

In this introduction, Gunn also explains something about poetry in the age of Sidney and Greville that must make any reader of Gunn’s own work who notices the dulled, impersonal tone of many of the poems, the lack of an individualized, quirky, confessional voice, realize that Gunn is writing about a phenomenon that he both recognizes and approves of. “Nowadays,” he writes,

the journalistic critical cliché about a young poet is to say that “he has found his own voice,” the emphasis being on his differentness, on the uniqueness of his voice, on the fact that he sounds like nobody else. But the Elizabethans at their best as well as at their worst are always sounding like each other. They did not search much after uniqueness of voice…. It would hardly have struck them that a style could be used for display of personality.

Sometimes, as with any decent essayist, Gunn’s critical essays provide us with the apologias or explanations for his life or his work that he did not see fit to display more explicitly. In his introduction to his selection of the work of Ben Jonson he offers a startling, almost comic, example of this:

It is interesting that most of those who have succeeded best in writing…within restraints both technical and passional, have been people most tempted toward personal anarchy. For them, there is some purpose in the close limits, and there is something to restrain.3

In a commentary on another of Greville’s late poems, “Sion lies waste,” Gunn writes about how

the simplicity of language, the directness of tone, and the lively variations in the verse movement, all serve to insist on the personal grief behind the public utterance. It is still a grief, however, that can sharply analyze: Greville never allows his feeling to eliminate his mind.

In an essay written in 1991, the year before his book The Man with Night Sweats appeared, Gunn wrote about a number of poems by Sir Thomas Wyatt dealing with the executions of Anne Boleyn and other friends of Wyatt’s, poems that had not been published until 1961. These poems by Wyatt have a tone of stark, shocked grief, often using lines without ornament or metaphor, in which he described actually seeing the executions from the Tower: “The bell tower showed me such sight/That in my head sticks day and night” or “And thus, farewell, each one in hearty wise./The axe be home, your heads be in the street./The trickling tears doth fall so from my eyes,/I scarce may write, my paper is so wet.”

In the sequence of poems at the end of The Man with Night Sweats, laments for friends who had died from AIDS, Gunn managed what David Gewanter in At the Barriers calls “the greatest elegiac sequence since Thomas Hardy’s Poems of 1912–13.” In these poems, most of which use an iambic meter and clear rhyming schemes, Gunn found a voice both formal and relaxed, a tone both impersonal and filled with detailed feeling; the poems have the same quiet, unshowy, hurt eloquence as Wyatt’s poems on the deaths of his friends. Just as Wyatt in his poem “In mourning wise” listed his friends who had been executed, Gunn in these poems went through each of his friends’ deaths as individual deaths, but in doing so, created what he praised in Wyatt’s poems: “Autobiographical detail, however discreet and allusive, is given a sudden symbolic force as in Yeats—though the symbol is more proportionate to reality than it ever was for Yeats.”

…It tears me still that he should die

As only an apprentice to his trade,

The ultimate engagements not yet made.

His gifts had been withdrawing one by one

Even before their usefulness was done:

This optic nerve would never be relit;

The other flickered, soon to be with it.

Unready, disappointed, unachieved,

He knew he would not write the much-conceived

Much-hoped-for work now, nor yet help create

A love he might in full reciprocate.

Between The Man with Night Sweats and his death, Gunn published a Collected Poems (1994) and one more volume of poetry, Boss Cupid (2000), which once more displayed his technical mastery of form and his insistence that form came in many guises, including looser ones. The range and the quality of Gunn’s work, and indeed its unevenness and his openness to change, has meant that making a selection from his work would require tact, intelligence, and some sympathy with his aims and systems. The clichéd version of Gunn’s career that August Kleinzahler outlines, with some distaste, in his perceptive introduction to what is a carefully chosen selection of Gunn’s poems goes as follows: “After going to hell in America, squandering his poetic gifts, Gunn was rehabilitated by the AIDS crisis and became an important poet once again because he became a feeling poet at last.”

In England, Gunn’s work, once he had abandoned ship and settled in California, received a mixed, often hostile response. Of his sixth collection, Jack Straw’s Castle (1976), Terry Eagleton wrote:

Gunn’s latest work, for all its newly-founded sensuous celebrations and delirious yieldings to blood-impulses, is merely the reverse side of the hard, thrusting, misanthropic egoism which motivated the formal leanness of his previous collections. The surf-riding rationalist hasn’t changed his spots; it’s merely that Californian sub-cultures offer an illusory escape from the pressing burdens of isolated selfhood.

Kleinzahler insists on finding con- nections and developments rather than fissures and gaps in Gunn’s development as a poet, reading the poems in Gunn’s first four collections as essentially brilliant early work. He argues that a transformation in Gunn’s tone, of which he approves, became noticeable as early as Part II of My Sad Captains (1961) but fully apparent in Moly, published a decade later. “A transformation had taken place,” Kleinzahler writes.

His poetry could accommodate a bit of relaxing. He will remain preeminently a poet of closure, intelligence, and will, as evidenced in the Moly poems. There was not an aleatory bone in Gunn’s body. He’s Handel, not John Cage…. His free-verse poems have a beginning, a middle, and an end. They develop rationally. The diction remains plain, the argument direct. His free verse is not at all prosey, and possesses its own kind of subdued music…. What has changed most demonstrably in the poetry in Moly and beyond is Gunn’s relationship with his environment. We are no longer dealing so much with allegories or notions of the city or character: the poems are now trained on actual people and places. If earlier on in the poetry it seemed as if there was no there there, now the there is very much in evidence.

Kleinzahler’s thesis suggests that what matters most in the poems of lament in The Man with Night Sweats, their very thereness, could not have been created without the years of experiment, the openness to both new forms and new experiences, which Gunn sedulously, indeed stubbornly, insisted on once he broke free of Yvor Winters. Gunn himself in an interview implied that his range of sympathies as a reader was something that came naturally to him as much as it was an act of will. “I’m not surprised,” he said, “that I have sympathies with such a broad range of poetry: I’m surprised that everybody doesn’t.” In his notebooks, some of which are quoted in At the Barriers, he wrote in 1964:

What do I want? Well, I want the new vision (I would use this word only to myself),—the new vision fastened in the material world by the style. The vision must be of the strength, variety, validity of life, implying the ethically good.

And four years later, he wrote: “I pass the romantic impulse through the classical scrutiny.” In his essay in At the Barriers Brian Teare manages to make interesting and credible connections between the seriousness of both Yvor Winters and Robert Duncan; he quotes from a notebook entry from Gunn in May 1980: “I do believe in poetry as an activity reflective of one’s life at its fullest—not only reflective, but it actually can be one’s life at its fullest.” It is likely that both of his old mentors who breathed in the air of California, an air both yellow and electric, which made such a difference to Gunn as both man and poet, would have approved.

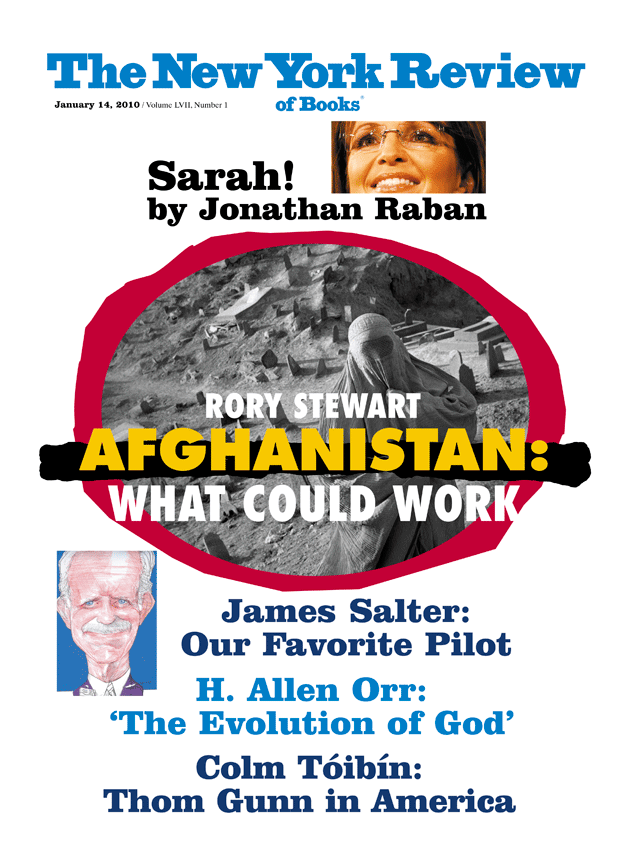

This Issue

January 14, 2010

-

1

In England Gunn was associated with Larkin in a group known as the Movement, which also included Kingsley Amis, Donald Davie, and Elizabeth Jennings. Movement poets, in response perhaps to the general postwar dullness, avoided the experiments of Modernism and the overblown rhetoric of Dylan Thomas, and wrote, in Donald Davie’s phrase about Philip Larkin, a “poetry of lowered sights and patiently diminished expectations.” In a new book, The Movement Reconsidered, edited by Zachary Leader (Oxford University Press, 2009), Alan Jenkins writes: “Denying the existence of the Movement, or denying that, if it existed, one had any part in it, seems to have started at the same time as the Movement itself.” Gunn was not only one of the most prominent of the Movement poets, but among the most vehement of the Movement deniers. ↩

-

2

1In his last book, Gunn composed a sequence of almost tender poems about Jeffrey Dahmer, the serial killer and cannibal. ↩

-

3

In a coda to At the Barriers, Robert Pinsky writes: “Thom the drug-taking, club-cruising leather-boy kept, under that surface, his center of shrewd, conservative good judgment and fine, traditional good manners. But it is equally true that under the surface of an earnest, conscientious, and polite university instructor, or an astute literary man, Thom kept his center of wild recklessness.” In Who’s Who, Gunn named his recreations as “Cheap Thrills.” ↩