We are all Europeans now. The English travel throughout continental Europe, and the UK is a leading tourist destination as well as a magnet for job seekers from Poland to Portugal. Today’s travelers don’t think twice before boarding a plane or a train, alighting shortly after in Brussels, Budapest, or Barcelona. True, one European in three never leaves home; but everyone else makes up for them with insouciant ease. Even the (internal) frontiers have melted away: it can be a while before you realize you have entered another country.

It wasn’t always thus. In my London childhood, “Europe” was somewhere you went on exotic foreign vacations. The “Continent” was an alien place—I learned far more about New Zealand or India, whose imperial geography was taught in every elementary school. Most people never ventured abroad: vacations were taken at windswept English coastal resorts or in cheery domestic holiday camps. But it was a peculiarity of our family (a side effect of my father’s Belgian childhood?) that we crossed the English Channel quite a lot; certainly more than most people in our income bracket.

Celebrities flew to Paris; mere mortals took the boat. There were ferries from Southampton, Portsmouth, Newhaven, Folkestone, Harwich, and points north, but the classic—and by far the most heavily traveled—route lay athwart the neck of the Channel from Dover to Calais or Boulogne. British and French Railways (SNCF) monopolized this crossing until the Sixties. The SNCF still used a pre-war steamer, the SS Dinard, which had to be deck-loaded by crane, car by car. This took an extraordinarily long time, even though very few cars used the service in those days. In consequence, my family always tried to schedule trips to coincide with departures by British Railways’ flagship ferry, the Lord Warden.

Unlike the Dinard, a tiny ship that bucked and tossed alarmingly in unsettled seas, the Lord Warden was a substantial vessel: capable of handling a thousand passengers and 120 cars. It was named after the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports—the five coastal settlements granted special freedoms in 1155 AD in return for services to the English Crown. A cross-Channel ferry service from Dover to Calais (an English possession from 1347 until 1558) dated from those same years, so the ship was well-christened.

As I remember it, the Lord Warden, which entered service in 1951 and was not retired until 1979, was a spacious modern ship. From its vast vehicle hold to its bright, capacious dining room and leatherette lounges, the boat promised adventure and luxury. I would rush my parents into breakfast, seizing a window table and ogling the ever-so-traditional menu. At home we ate sugarless cereals, drank sugar-free juice, and buttered our wheaten toast with sensible marmalades. But this was holiday-land, a time out of health, and concessions were made.

Half a century later, I still associate continental travel with English breakfast: eggs, bacon, sausages, tomatoes, beans, white-bread toast, sticky jams, and British Railways’ cocoa, heaped on heavy white plates emblazoned with the name of the ship and her owners and served by jocular cockney waiters retired from the wartime Merchant Navy. After breakfast, we would clamber up to the broad chilly decks (in those days the Channel seemed unforgivingly cold) and gaze impatiently at the horizon: Was that Cap Gris Nez? Boulogne appeared bright and sunny, in contrast to the low gray mist enshrouding Dover; one disembarked with the misleading impression of having traveled a great distance, arriving not in chilly Picardy but in the exotic South.

Boulogne and Dover were different in ways that are hard to convey today. The languages stood further apart: most people in both towns, despite a millennium of communication and exchange, were monolingual. The shops looked very different: France was still considerably poorer than England, at least in the aggregate. But we had rationing and they did not, so even the lowliest épiceries carried foods and drinks unknown and unavailable to envious English visitors. I remember from my earliest days noticing how France smelled: whereas the pervading odor of Dover was a blend of frying oil and diesel, Boulogne seemed to be marinated in fish.

It was not necessary to cross the Channel with a car, though the appointment of a purpose-built car ferry was a harbinger of changes to come. You could take the boat train from Charing Cross to Dover Harbour, walk onto the ferry, and descend the gangplank in France directly into a battered old station where the dull green livery and stuffy compartiments of French railways awaited you. For the better-heeled or more romantic traveler there was the Golden Arrow: a daily express (inaugurated in 1929) from Victoria to the Gare du Nord, conveyed by track-carrying ferries, its passengers free to remain comfortably in their seats for the duration of the crossing.

Advertisement

Once clear of coastal waters, the purser would announce over the Tannoy that the “shop” was open for purchases. “Shop,” I should emphasize, described a poky cubbyhole at one end of the main deck, identified by a little illuminated sign and staffed by a single cashier. You queued up, put in your request, and awaited your bag—rather like an embarrassed tippler in a Swedish Systembolaget. Unless of course you had ordered beyond your duty-free limit, whereupon you would be informed accordingly and advised to reconsider.

The shop did scant business on the outer route: there was little that the Lord Warden had to offer that could not be obtained cheaper and better in France or Belgium. But on its passage back to Dover, the little window did a roaring trade. Returning English travelers were entitled to a severely restricted quota of alcohol and cigarettes, so they bought all that they could: the excise duties were punitive. Since the shop remained open for forty-five minutes at most, it cannot have made huge profits—and was clearly offered as a service rather than undertaken as a core business.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, the boats were threatened by the appearance of the Hovercraft, a hybrid floating on an air bubble and driven by twin propellers. Hovercraft companies could never quite decide upon their identity—a characteristic 1960s failing. In keeping with the age, they advertised themselves as efficient and modern—“It’s a lot less Bovver with a Hover”—but their “departure lounges” were tacky airport imitations without the promise of flight. The vessels themselves, by obliging you to remain in your seat as they bumped claustrophobically across the waves, suffered all the defects of sea travel while forgoing its distinctive virtues. No one liked them.

Today, the cross-Channel sea passage is serviced by new ships many times the size of the Lord Warden. The disposition of space is very different: the formal dining room is relatively small and underused, dwarfed by McDonalds-like cafeterias. There are video game arcades, first-class lounges (you pay at the door), play areas, much-improved toilets…and a duty-free hall that would put Safeway to shame. This makes good sense: given the existence of car and train tunnels, not to mention ultra-competitive no-frills airlines, the main motive for taking the boat is to shop.

And so, just as we used to rush for the window seat in the breakfast room, today’s ferry passengers spend their journey (and substantial sums of money) buying perfume, chocolate, wine, liquors, and tobacco. Thanks to changes in the tax regime on both sides of the Channel, however, there is no longer any significant economic benefit to duty-free shopping: it is undertaken as an end in itself.

Nostalgics are well-advised to avoid these ferries. On a recent trip I tried to watch the arrival into Calais from the deck. I was tartly informed that all the main decks are kept closed nowadays, and that if I insisted upon staying in the open air I would have to join my fellow eccentrics corralled into a roped-off area on a lower rear platform. From there one could see nothing. The message was clear: tourists were not to waste time (and save money) by wandering the decks. This policy—although it is not applied on the laudably anachronistic vessels of (French-owned) Brittany Ferries—is universally enforced on the short routes: it represents their only hope of solvency.

The days are gone when English travelers watched tearily from the deck as the cliffs of Dover approached, congratulating one another on winning the war and commenting on how good it was to be back with “real English food.” But even though Boulogne now looks a lot like Dover (though Dover, sadly, still resembles itself), the Channel crossing continues to tell us a lot about both sides.

Tempted by “loss leader” day-return fares, the English rush to France to buy truckloads of cheap wine, suitcases of French cheese, and carton upon carton of undertaxed cigarettes. Most of them travel by train, transporting themselves or their car through the Tunnel. Upon arrival, they face not the once-forbidding line of customs officers but a welcoming party of giant hypermarchés, commanding the hilltops from Dunkerque to Dieppe.

The goods in these stores are selected with a view to British taste—their signs are in English—and they profit mightily from the cross-Channel business. No one is now made to feel remotely guilty for claiming his maximum whisky allowance from a stone-faced sales lady. Relatively few of these British tourists stay long or venture further south. Had they wished to do so, they would probably have taken Ryanair at half the price.

Are the English still unique in traveling abroad for the express purpose of conspicuous down-market consumption? You won’t see Dutch housewives clearing the shelves of the Harwich Tesco. Newhaven is no shopper’s paradise, and the ladies of Dieppe do not patronize it. Continental visitors debarking at Dover still waste no time in heading for London, their primary objective. But Europeans visiting Britain once sought heritage sites, historical monuments, and culture. Today, they also flock to the winter sales in England’s ubiquitous malls.

Advertisement

These commercial pilgrimages are all that most of its citizens will ever know of European union. But proximity can be delusory: sometimes it is better to share with your neighbors a mutually articulated sense of the foreign. For this we require a journey: a passage in time and space in which to register symbols and intimations of change and difference—border police, foreign languages, alien food. Even an indigestible English breakfast may invoke memories of France, implausibly aspiring to the status of a mnemonic madeleine. I miss the Lord Warden.

—This piece is part of a continuing series of memoirs by Tony Judt.

This Issue

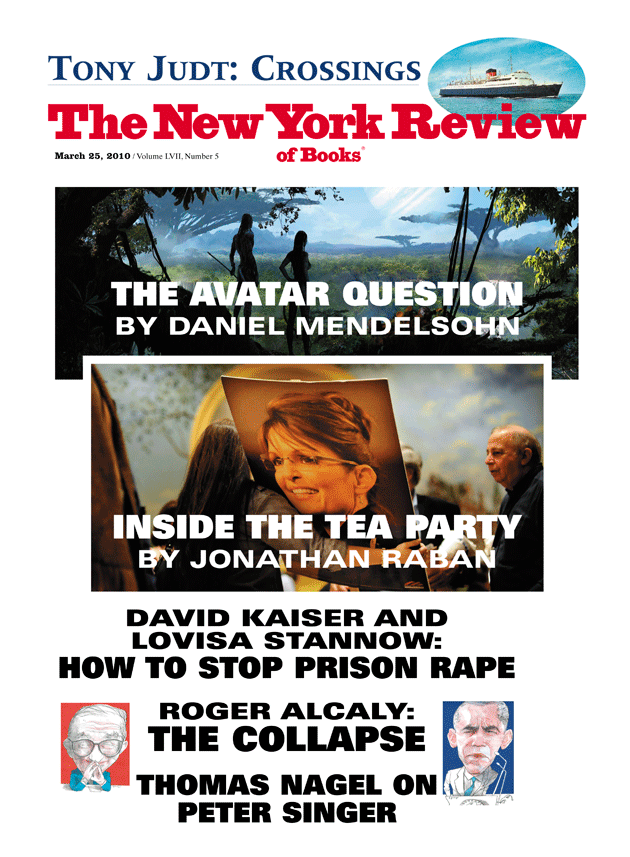

March 25, 2010