Down the middle of the great hall of medieval sculpture in the Metropolitan, under the banners, march thirty-six men and one boy, carved from alabaster, most of them around sixteen inches tall: tiny mourners from the tomb of John the Fearless, one of the Valois dukes of Burgundy. They will be marching at the Metropolitan until May 23, and they eminently deserve a visit. Shrouded in thick cloaks that fall in heavy folds, many of them sporting large hats or hoods that sometimes conceal their faces, the figures at first seem hard to tell apart—especially when you face them from the front and see them in their two close-set lines, mustered like the soldiers of a tiny army.

As you walk around them, as you examine and compare, you begin to see how varied they are. A bishop, his face as stony as the material he is made of, calmly carries a crosier, its curling top and his miter both tiny bravura set pieces of carving. Others clutch books, the large ones from which priests sang services, holding them open for use, saving a place with inserted fingers, or letting them dangle. There are both secular clergy (ordinary priests) and “religious” (members of orders). Peer under the hats and hoods, and you see that there are also laymen: bearded, mustached, elegant courtiers, daggers hanging at their sides, swathed in clerical-looking cloaks for this occasion only.

If the rich folds of fabric endow the figures with majesty, their hands give them life. Delicately detailed, their fingers a little stubby, their motions restrained—monks and courtiers learned to follow rigorous codes of gesture—they clasp one another, touch belts and garments, grip beads, books, and pouches, rise pleadingly in the air, and raise folds of cloth to wipe wet eyes. These quietly eloquent hands express every imaginable form of mourning. The most poignant mourner of all, who wears a neat two-pointed beard, pinches the bridge of his nose with a delicately raised left hand in order to hold back the rush of tears.

Carved by Jean de la Huerta and Antoine le Moiturier between 1443 and 1457, the mourners normally spend eternity processing through the magnificently frilly alabaster arcade that surrounds the base of the tomb of John the Fearless, beneath the recumbent effigies of the duke and duchess. Originally located in the Carthusian monastery of Champmol, west of Dijon, whose members prayed for the souls of John and his wife, the tomb was dismantled and partly destroyed in the French Revolution. Almost all of the surviving statues ended up in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dijon, where they have been incorporated into a restoration of the tomb. The mourners will return there, after they complete their artistic pilgrimage to the Met and six other American museums, from Richmond to San Francisco, ending with a stop in Paris.

In Dijon, the mourners are low to the ground, fixed in place and visible only from the side. But they were carved at a time when painters finished the backs of altarpieces to perfection to please the all-seeing eye of God. To see them in the round is to be dazzled by the skill that their creators lavished on details that they did not expect human visitors to see. It is also to be plunged back into all the colors and contradictions of Renaissance life.

John the Fearless was long dead when these effigies were carved. He had been assassinated in 1419, on the orders of the French dauphin—the Valois prince who would ascend the throne, thanks to the efforts of Joan of Arc, as Charles VII (John had ordered the assassination of Charles’s uncle, Louis d’Orléans). His violent death came as a terrifying shock to his family and supporters: when his young son and heir heard the news, he suffered a nervous breakdown. His wife fainted, and the city of Ghent rang with loud laments. Many of the glossy clerics and hard- bitten men-at-arms who had taken part in his funeral procession were themselves dead and forgotten by the 1440s, lost to disease and the endless tale of violence that was the Hundred Years’ War, which English-speakers know best from the other side and very partially, thanks to Shakespeare’s Henry V. But his son remembered, and eventually commemorated his father’s death and funeral with these exceptionally beautiful statues.

In the first half of the fifteenth century, the ducal Burgundian branch of the Valois family was richer, and for long periods more powerful, than their royal relatives. John’s father, Philip the Bold, who had married a Flemish countess, joined the rich ducal lands in the French southeast with the even richer urban counties of Flanders and Artois to the north. John’s son, Philip the Good, enlarged Burgundy and made it even stronger. He drew enormous resources from the trading and manufacturing cities of the Netherlands and worked to turn his lands into an independent kingdom. This shared family vision would bring his son, Charles the Bold, to his death in a ditch at the Battle of Nancy in 1477.

Advertisement

If Burgundian power was a dream that ultimately vanished, Burgundian splendor was the dukes’ unforgettable accomplishment. They liked to live in the great cities, Paris, Bruges, Ghent, and Brussels, where they frequented the most discriminating dealers in gems, precious metals, and tapestries, and where they could employ—and spend time with—the most gifted artists. They spent lavishly and well. Jan van Eyck, whom even Italians saw as the greatest painter of the first half of the fifteenth century, served Philip the Good as both painter and diplomat.

The Burgundians knew how to put on a show. In 1454, after Constantinople fell, the Burgundian chivalric order of the Golden Fleece, which Philip the Good founded, held a magnificent banquet at Lille. Colorful allegories burgeoned like forsythia in the spring: a woman riding an elephant, led by a colossal Moor, explained that she represented Religion, and pleaded to be rescued. The noble members of the order vowed, one and all, to go on crusade and win back both Constantinople and Jerusalem. More sensibly than some modern crusaders, they then returned home. Yet every great occasion had its spectacle—and every spectacle its magnificent setting. For power rested in no small part on the artists and writers who staged court performances, and on the wealth that paid for them.

Their eyes as open as their purses, the Burgundians encouraged the artists who worked for them to experiment with materials and pigments, subjects and composition. The dukes were especially eager to adorn their residences in Dijon, their capital, and elsewhere, which they visited only for short periods in most years. Two of their greatest projects were monuments in which processions of mourners circled the base of a great stone slab topped by one or two full-length figures of the duke and duchess. The first was the tomb of Philip the Bold, created by his son, John the Fearless. John’s own tomb was crafted in direct imitation of his father’s monument by his heir, Philip the Good.

To meet the mourners, then, is to confront official art—but it is also to marvel at a product of one of those moments when artists and energies fused in a creative critical mass. Think of Gauguin and Van Gogh in Arles, or Picasso and Braque at the Bateau Lavoir—or Brunelleschi, Donatello, and Ghiberti in their Florentine workshops, carrying out their own explosive experiments with the expressive capacities of stone while Claus Sluter and his colleagues created mourners for Philip the Bold. No wonder that those little off-white hands, curled and pointing, can express so much. De la Huerta and Le Moiturier carved and polished for patrons with precise expectations and exacting standards, and competed with one another and other artists who constantly tried to make it new.

As Sophie Jugie makes clear in the catalog that accompanies this exhibition, these statuettes commemorate the ritual mourning that followed the death of John the Fearless. Royal and noble funerals were the grandest of occasions, accompanied by multiple processions—especially when “the deceased had commissioned, alongside a tomb for his body, a second for his heart and third for his entrails,” as was normal practice in France (though not in Burgundy). Burgundian records show that a gold drapery covered the duke’s coffin, banners waved and canopies provided protection from the elements, and the duke’s arms and armor were carried with the coffin, as his body headed for its resting place. All the laymen who took part, from family members to pages and grooms, actually wore hooded black cloaks that made them resemble, for a time, the priests and monks next to whom they walked. Oddly, John’s body was clad only in vest, trousers, and shoes—a decision that surprised some observers.

Executed a generation and a half after the events, the mourners symbolized, rather than portrayed, the Burgundian clerics and courtiers at their public work of mourning. Happily, the Metropolitan, with brilliant timing, has made it possible not only to see the mourners themselves, but also to visualize the event that they commemorate, as their contemporary visitors could, in something of its original drama and color. Not far from the great hall, another sumptuous creation of the artistic world in which the mourners took shape is on display. One of the glories of the Cloisters, the Book of Hours created by the three Limbourg brothers for Jean, Duke of Berry, the uncle of John the Fearless of Burgundy, has been disassembled for restoration. Until June 13, you have the rare opportunity to see its individual pages, beautifully displayed and explicated by expert, insightful commentary, in the Robert Lehman Wing of the museum. As you enter and explore the tiny, vivid world that the Limbourg brothers created, with colors that run from bright pastels to deep glowing ultramarine, and lines that rapidly took on a stunning confidence, elegance, and expressiveness, you realize that these illuminators were carrying out their own series of experiments on the micro scale into the limits and possibilities of a form of art.

Advertisement

The Limbourgs’ miniatures set events from the history of the Church into a late medieval world of costume and architecture. Accordingly, they open a vivid series of windows onto the material and social world in which Burgundian rulers lived and clerics and courtiers mourned the dead. They help us to imagine the funeral processions taking place, and to appreciate what their perpetuation in alabaster meant to those who paid for them and carried them out. The fantastic world of the Burgundians, the Limbourgs teach us, was stalked by death. Even nobles who escaped political murder were likely to fall victim, as Jean de Berry did, to the plague. The Black Death had cut the population of Europe almost in half in the years 1348–1351 and it recurred, over and over again, in the fifteenth century. Every feast of the Golden Fleece could turn without warning into a Masque of the Red Death.

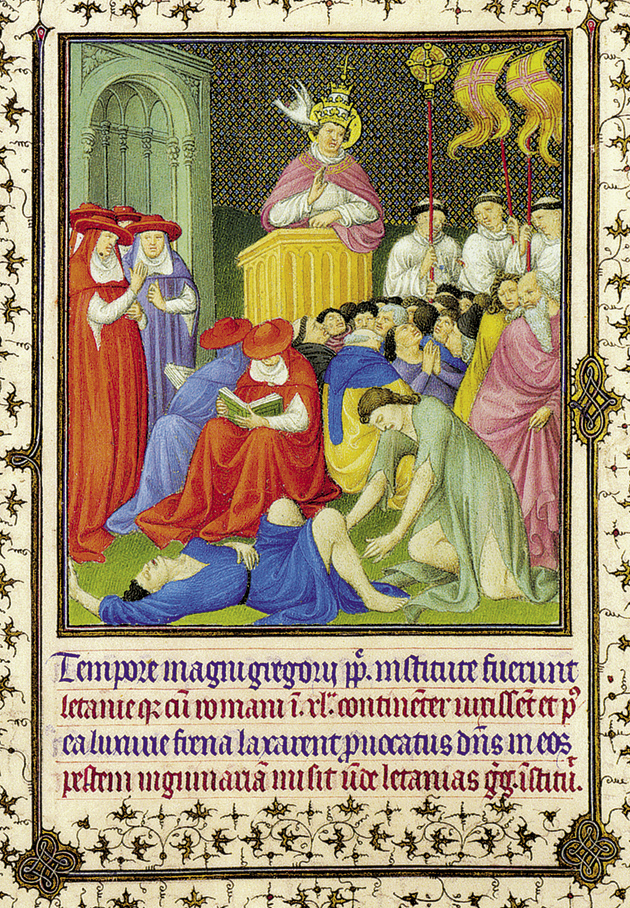

Cloisters Collection/Metropolitan Museum of Art

‘Institution of the Great Litany’; illumination by the Limbourg brothers from the Book of Hours of Jean, Duke of Berry, circa 1405–1409. The Latin caption reads: ‘In the time of Pope Gregory the Great the litanies were instituted. At one time the Romans lived in continence during Lent, and afterward they relaxed all moral restraints. God, thus provoked, sent them the bubonic plague. Following this, Gregory instituted the litanies.’

None of the Limbourgs’ images are more striking—or more frightening—than those that portray Gregory the Great, who became pope in 590 when the plague killed his predecessor, Pelagius II. Instructed by the Holy Spirit, he speaks to cardinals, priests, and ordinary people. On the ground in front of him lies a stricken man, dressed in a brilliant blue robe that contrasts sharply with the cardinals’ red gowns. Another man, clad in pale green and propped on one knee, seems to sneeze and collapse toward the man on the ground.

In a second image, a dead man in blue lies on the ground, legs drawn up by rigor mortis. Gregory leads a procession of cardinals and priests, widows and virgins. Next to the pope, a figure in yellow, arm raised in benediction, yawns in terror and collapses stiffly. Most chilling of all is a third image—one of flagellants in black hats and white hoods, most of them bare to the waist, carrying their dragon flag, and some of them whipping others on the back in the hope of averting the plague that was the most concrete imaginable sign of God’s wrath. The Burgundian patrons and their artists, in other words, commissioned and made and enjoyed their objects of art and luxury in the midst of suffering best imagined in the visual terms of Ingmar Bergman’s Seventh Seal. Processions—the close-packed processions so vividly depicted by the Limbourgs—were not holiday amusements but serious efforts to “bestow on sorrow a form and turn it into something beautiful and lofty.”1

The dead, in this Burgundian world, did not inhabit sanitary cities of their own, far from the living. They rotted in the ground in graveyards—as more than one of the Limbourgs’ miniatures vividly showed—and rested embalmed in tombs that were centrally located and frequented by visitors. Sometimes they rose from their graves to address the living. Mostly the bodies rotted, while their souls submitted in Purgatory, like the living flagellants, to the tortures administered by devils, and begged the living for prayers that might abridge their time of purification.

The Limbourgs (and their patron) were less interested in devils than the Dutch artist who around 1440 illustrated the Hours of Catherine of Cleves—a jewel of the Morgan Library, magnificently displayed there, disbound, until May 2.2 But hideous little creatures blow lights out, tempt saints with dancing girls, and stage vicious attacks in the miniatures of the Belles Heures. The dukes must have worried, like Hamlet, that death might mean something much worse than mere extinction. The churches they endowed and the monks they supported were fortifications and armies arrayed to protect their souls from some of the suffering they had earned. The skill and devotion, the money and the art and craft that went into making the mourners—all, like the grieving processions themselves, went to express a hope, hard to fathom now, that memory and mourning could compensate for sin, and that sacred art could grant such evanescent things something like permanence.

And yet it would be an error—an error of anachronism, the easiest kind for moderns to make—to miss the spiritual life of the mourners. More than one of the figures fingers a string of chunky beads (one has even dropped his set). These are rosaries, the devotional devices that took on their definitive shape in the early fifteenth century, thanks largely to the efforts of another member of the same order that commemorated John the Fearless, the Carthusian Dominic of Prussia. Like books of hours, rosaries represented an effort to give religious observance, both personal and communal, a new depth and power.3 As clerics and laymen clicked their way through the Rosary, saying prayers to Mary and the Our Father, they imagined scenes from the life of the Savior and reflected on their different mysteries. Techniques of contemplation—the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were fertile in these—ensured that their piety remained fresh, and that they brought to their prayers for the dead the vivid images and felt emotions that could make them effective. Prayers and processions were a frail defense against the dark—but not a meaningless one.

The mourners—and the other sculptures of their time, displayed near them, which include three energetic figures from the tomb of Philip the Bold—embody a lost world of grief and prayer as well as consummate artistry. Their display allows them to be wholly seen—as the arcades they normally inhabit do not. It seems a pity that the imaginative curators at the Metropolitan did not devise an ingenious digital way to show the viewer what these little men would have looked like in their original state: not stripped of color, but decorated in polychrome, as a few of the books and pouches that hang from their belts still are. All the more reason, then, to combine contemplation of the mourners with a visit to the Belles Heures a few yards away.

-

1

Johan Huizinga, The Autumn of the Middle Ages, translated by Rodney J. Payton and Ulrich Mammitzsch (University of Chicago Press, 1996), p. 56; [reviewed in these pages](/articles/archives/1996/apr/04/ah-sweet-history-of-life/) by Francis Haskell, April 4, 1996. ↩

-

2

“Demons and Devotion: The Hours of Catherine of Cleves,” an exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum, New York City, January 22–May 2, 2010. The catalog of the exhibition is by Rob Dückers and Ruud Priem, The Hours of Catherine of Cleves: Devotion, Demons and Daily Life in the Fifteenth Century (Abrams, 2010). ↩

-

3

See Eamon Duffy, Marking the Hours: English People and Their Prayers, 1240–1570 (Yale University Press, 2006); [reviewed in these pages](/articles/archives/2007/feb/15/the-one-and-only-book/) by Christopher de Hamel, February 15, 2007. ↩