Why was there a revolution in France in 1789? Historians have rarely been in consensus about the answer and most currently credit a variety of factors including economic hardship, financial crisis, political mismanagement, and cultural and ideological transformation. Robert Darnton wants to add to the list. His latest book, The Devil in the Holy Water, or the Art of Slander from Louis XIV to Napoleon, focuses on the literature of calumny, which took the form of scandal sheets known as libelles.

The work of Paris’s Grub Street of impoverished writers, libelles played a major part, Darnton maintains, in shaping public opinion in the years leading up to 1789, and they contributed significantly to the character of the subsequent Revolutionary regime. He remains true to a position with which his work has been associated for nearly forty years—that “low literature” had a bigger impact on the outbreak of the Revolution than the “High Enlightenment.”1 The Devil in the Holy Water modifies and adds nuance to this view but largely maintains it. Yet the book also has a larger ambition, namely to provide a thorough analysis of the literature of calumny by raising issues of freedom of speech and access to information that have wider relevance, including to our own world.

In these pages two years ago, Darnton introduced readers to one member of the rum group responsible for the production of Old Regime libelles: Anne Gédéon Laffitte, marquis de Pelleport,2 “a scoundrel, a reprobate, a rogue, a thoroughly bad hat” in his estimation. Pelleport was the author of the work, Le Diable dans un bénitier, that gives Darnton’s book its title. This déclassé nobleman’s prior small claim to fame was that in the 1780s he inhabited a cell in the Bastille adjacent to the Marquis de Sade’s. While the latter was writing The 120 Days of Sodom, Pelleport was composing his own picaresque and obscene novel, Les Bohémiens.

The book bombed. Only a handful of copies are extant, and it seems to have been almost wholly unread until Darnton rescued it from obscurity by publishing it last year in English translation and this year in French—and by hailing it as a literary masterpiece.3 This may strike its modern-day readers as a generous verdict on what seems to me an amorphous and somewhat tedious work, which pays only turgid homage to Rabelais, Lesage, Voltaire, and Sterne.

Yet whatever the literary merits of Les Bohémiens, the novel also has significant documentary value. It provides a vivid, colorful, and, Darnton believes, largely plausible account of the Parisian Grub Street that is the subject of his new book. This includes a vicious and full-out assault on one of Pelleport’s principal adversaries, the libelliste Charles Théveneau de Morande, uncharmingly presented as having “a mouth from whose corners there is a constant trickle of livid pus.” Morande’s career—which is also finely illuminated in Simon Burrows’s recent biography4:—offers an excellent introduction to the Old Regime world of slander.

A cavalry officer during the Seven Years’ War, Morande thereafter spent a dissolute and debauched youth in Paris—gambling, opera girls, homosexual pimping, extortion, and so on—before fleeing the police in 1770 and establishing himself in London. The English capital’s Grub Street milieu was even more powerful than its Parisian counterpart and it housed a phalanx of French expatriate authors, many of them publishing through the Genevan bookseller David Boissière on St. James Street. It was from this well-defended bolt-hole that in 1771 Morande published an epically slanderous work entitled Le Gazetier cuirassé (The Armor-Plated Gazeteer).

Much of Morande’s slander was expressed in what were known as anecdotes. These were more than simple anecdotes or droll stories. Anecdote was a term of art, used to describe shards of information about the private lives of public figures that were somehow too scandalous to print in any legitimate form, but that were of putative political importance. Thus Le Gazetier cuirassé combined an apparently serious political purpose—namely an attack on the alleged “ministerial despotism” of Louis XV’s government—with the recounting of salacious tittle-tattle about the private corruption, domestic infidelity, and freewheeling and sordid sexual antics of pretty much the entire political and religious establishment, in a style combining verve with humor and mockery.

The effect was all the more breathtaking in that, though much of his book comprised unconfirmable innuendo and manifest falsities, Morande also seemed worryingly well informed about the world he described. Besides pumping former cronies back in France about elite vice and sexual deviation, he was also well connected in London through the notorious transvestite the chevalier d’Eon.

Advertisement

Many of the lofty characters in Le Gazetier cuirassé were referred to in code or under cover of anonymity. This playfulness only added to the fun: keys to the code circulated, and in any case most Enlightenment readers liked riddles and puzzles, and rose accordingly to the challenge. As Darnton puts it, the work “shock[ed readers] by slandering the great, and it amuse[d] them by hiding the slander in allusions that [had] to be puzzled out.” In an odd, backhanded way, this seemed to many a more inclusive form of politics than anything the Bourbon dynasty could offer. The libelle purported to be “unveiling” (the term was widely used) vital information of public interest that the government was withholding from public view.

In the event, Le Gazetier cuirassé traded in shock and amusement so effectively that it made Morande a fortune. It went into numerous editions and became one of the most popular clandestine texts circulating in France in the 1770s and 1780s, alongside the most daring philosophical works of Voltaire and d’Holbach.

In addition, the work’s success also gave Morande the means to make a second fortune. For his corruscatingly piquant and mockingly vicious tales had frightened the French political elite: more secrets might come into the open, more skeletons might be paraded outside their closets. Responding artfully to this apprehension, Morande developed a sophisticated line in blackmail, informing potential targets that he possessed harmful information about them, and inviting them to pay him to prevent its publication.

In 1774, he went for broke, extending his system to the very highest level: Louis XV and his principal mistress, Madame du Barry. He let it be known from across the Channel that he had even worse tales to tell about them both in a work to be entitled Mémoires secrets d’une femme publique—an overt allusion to du Barry’s past as a courtesan. After several fruitless attempts to bring him to heel, the royal government dispatched to London the playwright-adventurer Caron de Beaumarchais on a secret mission to intimidate Morande, or else to buy him off. The latter stratagem did the trick, handsomely. Morande deigned to receive what was effectively a king’s ransom, and also an annual pension from the crown that could be withdrawn at the first sign of misbehavior. Beaumarchais remarked to the Paris police chief Sartine that he had converted Morande from poacher to gamekeeper. Over the next two decades, Morande produced regular reports on libelous activity going on in London that was blackening the French crown. He thereby became the sworn enemy of most of his fellow denizens of Grub Street in both Paris and London.

Darnton regards Le Gazetier cuirassée as the starting point for a system of political slander that developed apace and became increasingly important in subsequent decades. Morande had laid the egg, but owing to his well- remunerated change of political tack, other libellistes hatched it. A large group of texts emerged, building on and elaborating Morande’s legacy. These were often published at length and over a long period. Although some were single volumes, there were ten volumes to L’Observateur anglais, ou correspondance secrète entre Milord All’Eye et Milord All’Ear (1777–1778), and no less than thirty-six to the Mémoires secrets pour servir à l’histoire de la république des lettres en France (1777–1789). These and similar texts shared the qualities of being, in Darnton’s expert view, “slanderous, tendentious, wicked, indecent, and very good reading.” “Secret histories” chockful of bite-size anecdotes henceforth were in strong demand, which the royal government failed to stifle.

The Morande story line would be replayed on a number of occasions under Louis XVI, who succeeded to the throne in 1774, as the world of slander took an increasingly farcical turn. French ministers labored to stop salacious stories at the source, conniving in blackmail attempts, chasing down French nationals in London, and doing everything in their power to stop what proved to be an unquenchable source of scurrility. Threats, censorship, arrests, and arbitrary embastillement provided tested methods of keeping a measure of control over such works within France. In London, the crown also tried bullying, kidnapping, assassination, and pressuring Parliament into changing the English libel laws. Despite the reformed Morande’s very best efforts, London became an essential outpost of Paris’s Grub Street. Operating with apparent impunity from an indeterminate location, it generated a transnational flow of scurrilous anecdotes.

Morande’s career is an excellent point of entry into the intriguing world of Old Regime slander, in which Darnton entertainingly revels. Although Darnton wears his learning exceedingly lightly, an extraordinary amount of painstaking primary research has gone into the production of this book. Just to riffle lightly through its lengthy footnotes is to discover that Darnton has lost none of his archival energy and ingenuity. This allows the reader to follow at close hand the intersecting careers of his numerous dramatis personae, often puffed up with their own loquacious braggadocio—though the lives of the figures are sometimes so picaresque, so full of passages into and out of clandestinity, across the Channel and back, into and out of royal favor, and so replete with zigs and zags, simulations and dissimulations, and ruptures and reconciliations that the effect is dizzying.

Advertisement

The issue is compounded in that Darnton’s two aims sometimes compete and conflict. On one hand, he uses a historical, diachronic approach in order to measure the political impact of the libelles. On the other, his analysis of the morphology of early-modern slander is done in quasi-anthropological, largely synchronic mode. The mix makes for a surprisingly difficult (considering Darnton’s exceptional expository skill) yet ultimately rewarding and thought-provoking book.

The genealogy of slander can be traced back to antiquity. Darnton locates the earliest direct antecedent of the libelles in the sixth-century Byzantine historian Procopius’ Anecdotal History, and also cites as early exemplars the pasquinades of Pietro Aretino in Renaissance Italy and the mazarinades of the Fronde, France’s abortive seventeenth-century civil war. Libelles could take many forms—chronicles, biographies, poems, dialogues, or correspondence, for example—and shaded into journalism at one end, fiction at the other.

The golden thread that unites them all—including more modern versions—is that they were adept at reducing “complex events to the clash of personalities.” Their authors realized that “names make news,” and they narrated politics through individual adventures, true or false. Collectively, they constituted “an outlook on political authority that can be characterized as folklore or mythology.” Darnton approaches the “folklore” of Old Regime scandal in much the same way that Vladimir Propp tackled Russian folk tales and Roland Barthes the “mythologies” of France in the 1950s—that is, in a manner that is more alert to the repetitions that identify the genre rather than to differentiating characteristics between the works in question.

The base unit, the building block, of all slanders in this period is the anecdote, the expressive mini-story concerning private life that illuminates character in a way that has alleged implications for public life. Some of the “stories” are true, though that is largely irrelevant, for in all forms of the genre, plausibility trumps truth, the striking is preferred to the everyday, plagiarism wins out over originality, and the general rule of thumb is se non è vero, è ben trovato.

Such gossipy tales may well have started their lives in conversations in a Parisian coffeehouse or a salon or a chance encounter in a park or promenade. Police surveillance of all these locales obliged bearers of such nuggets of purported news to write them down on scraps of paper—which one imagines being exchanged in subtle handshake maneuvers similar to those used on Baltimore street corners, as depicted in The Wire. These dangerous notes might subsequently be swept up in police arrests and body-frisking. In a virtuoso demonstration, Darnton shows how these scraps of paper, which he has paintakingly reassembled from police archives, resemble the paragraph-length historiettes that form the substance of most of the printed slander sheets at the heart of his analysis. Most “secret histories” retain the conversational tone and structure of their oral origins.

Conversational and chatty, obsessed with celebrity over hard news stories, reveling in fakery and make-believe, evading censorship and intruding voraciously on individual privacy, the Old Regime world of slander, Darnton holds, resembles the modern-day blogosphere. His Grub Street thus morphs into “the early-modern blog,” which, he claims, “played an important part in the collapse of the Old Regime and in the politics of the French Revolution.”5 The equation may need some further demonstration for those of us who read blogs mainly to catch up with the English cricket scores. But I am out of line here—the readership of blogs in North America far exceeds that of the daily press, and their rumor-fueled and intermittently salacious character does seem to invite comparisons with Darnton’s Old Regime of slander. As Darnton notes, it is a moot point whether such blogs are undermining conventional politics today as they did in the late-eighteenth-century world that he has analyzed. But as I shall suggest, it is not completely self-evident that they had such a powerful effect in the Old Regime world either.

For Darnton’s purpose, it is asking a lot to believe that this accumulation of prurient and scandalous stories—ignoble pearls looped casually together on a loose thematic string—were so powerful politically and culturally. Did the libelles really matter as much as Darnton claims? In the nineteenth century, political conservatives ascribed the causes of the Revolution to Enlightenment luminaries. Where the cry was once C’est la faute à Voltaire! C’est la faute à Rousseau!, Darnton would clearly prefer C’est la faute à Morande! C’est la faute à Pelleport! The writings of such minor but influential figures, he believes, had a drip effect on public opinion that served to sap the authority of the crown and to desacralize and delegitimate divine right absolutism.

This may indeed have been the political mission of many libellistes. But was it effective, and how can we tell? Many of these works did circulate extensively on the clandestine book market and must therefore have been widely read. But it is difficult to find concrete examples of reader reception—perhaps it would be socially embarrassing to confess to reading such works or to admit being influenced by them. In addition, there were many other competing texts in circulation that criticized the court and the nobility without recourse to crude slander, so it is quite conceivable that French men and women arrived at critical attitudes toward the political establishment without ever having read a single libelle.

It makes a good story to see low literature as more politically influential than the theories of the High Enlightenment—but it is not necessarily true. Indeed, the division into “high” and “low” may be more problematic than Darnton allows, for many Enlightenment figures, not least Voltaire, were past masters at the arts of slander. Grub Street did not enjoy a slander monopoly. Nor was political slander restricted to the last decades of Old Regime France. Le Gazetier cuirassé was less original than Darnton implies. Many of the Frondeur mazarinades he earlier mentioned packed much the same punch. Strong repression crushed the expression of opinion during most of the reign of Louis XIV, but political slander recovered in his last years and flourished in the Regency following his death in 1715 and then again in the 1740s and 1750s in the era of Madame de Pompadour. Morande was less original than he may appear.

Furthermore, for the monarchy to be “desacralized” by the libelles, one needs to be convinced that it was ever “sacralized,” and it is uncertain that the French monarchy’s claims to divine right were ever as widely believed as the ideologists of divine-right absolutism declared. Moreover, most anti-monarchical slander focused on Louis XV, Louis’s XVI’s life offering fewer (though still juicy) opportunities for titillation. When we have something approaching a genuine snapshot of public opinion about the monarchy in 1789—the books of grievances, or cahiers, drawn up across the land for the meeting of the Estates General—we find their authors competing against one another in expressions of fawning royalism. There might even be a case for arguing that at the outbreak of the Revolution the king’s reputation had prevailed over the designs of political slanderers.

Of course, the royal government would not have engaged so much time and effort in tracking down libellistes unless it felt in some way threatened. But perhaps ministers were just being too touchy. On the eve of the Revolution, the writer Louis-Sébastien Mercier recommended simply treating such works with the disdain and scorn they deserved, on the grounds that to do more risked making their authors think themselves more important than they were. This might have been a more effective political option, though it was one that the rhetoric of absolutism would have difficulty accommodating. In the event, the cloak-and-dagger caperings back and forth to London made the royal government look foolish—and indeed more repressive of free speech than it really was.

The tactic of alternating repression and acceptance of demands made by political blackmailers meant that ministers could end up “censoring” works that had never been written—and paying for the privilege of doing so. At other times, whole print runs were purchased by government agents and sent to languish in the cellars of the Bastille. The government’s responses thus poured oil on seditious fires and even allowed disreputable libellistes to pose as martyrs in the cause of free speech. That situation was arguably more damaging to the monarchy than the content of the libelles.

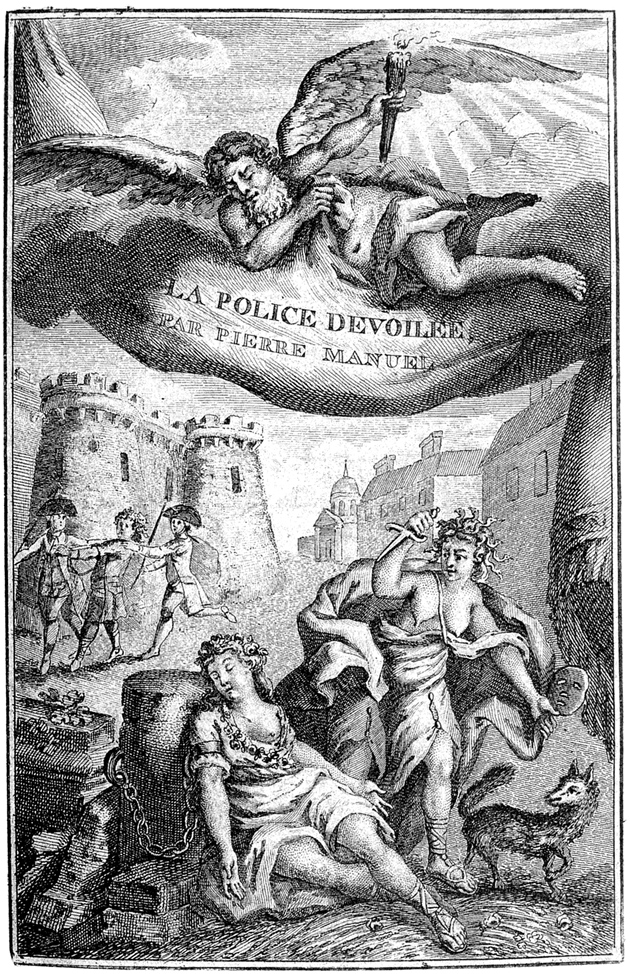

One of the curious consequences of the storming of the Bastille in 1789 was that it released into public circulation the assembled archives of Old Regime slander, which could henceforward circulate with unheard-of freedom. A central figure in this development was Pierre Manuel—another apparently minor Grub Street figure whom we see in new and enhanced light as a result of Darnton’s research. A hack writer who before the Revolution was on the fringes of the trade in clandestine slander, Manuel had done time in the Bastille—and followed up by becoming a police spy, something he kept off his curriculum vitae after 1789. He was closely linked to the network of itinerant peddlers who were diffusing clandestine literature in Paris, and this provided a publicity trampoline that vaulted him in 1789 to a post in the police department in the Paris municipal government, or Commune. There, and in the National Convention to which he was elected in 1792, he developed a reputation as an advanced patriot of Jacobin persuasion.

Crucial in this was his publication in 1789–1790 of a series of sensational assaults on the Old Regime political establishment, La Bastille dévoilée, La Chasteté du clergé dévoilée, and La Police de Paris dévoilée, three “unveiling” works in some seven revelation-packed volumes. His role as a police official in the Commune at the outbreak of the Revolution had given him direct access to the pre-1789 police and Bastille archives. Manuel thus built a Revolutionary political career on rummaging through the cellars of the ancient fortress. His slanders could be presented as telling the truth about the Old Regime.

The freedom of speech that was one of the Revolution’s prime aims allowed political slanderers to turn up the volume and extend the reach of their works, thus ensuring that the public appetite for political titillation that the libellistes had cultivated prior to 1789 was not diminished. As Darnton shows, Manuel’s influential volumes offered much the same diet of pre-Revolutionary tittle-tattle, targeted at the court, aristocratic, and ecclesiastical elites. Their titles even came complete with the “unveiling” metaphor that had characterized pre-Revolutionary libelles. While those texts had retailed alleged conversations and rumors, however, these new volumes could claim to unfold a truthful and realistic narrative by drawing on the authentic archives of Old Regime vice, crime, and folly.

Moreover, Manuel presented his motives in a new and distinctive way: whereas under the Old Regime, prurience and mockery had set the tone, giving the genre a disreputable air, now the alleged aim was altruistic patriotic duty. The true Revolutionaries were supposed to live by an unimpeachable moral code, so the personal failings of pre-1789 political figures could be seen in an even blacker hue. The epigraph of one of Manuel’s titles was “Publicity is the safeguard of laws and morals.” In Darnton’s account, Manuel and his ilk thus effectively invented a highly influential and long-lasting version of the political culture of the Old Regime, and created a collective memory to go with it.

As under the Old Regime, however, low political slanders were most effective where they drew on and supported existing ideological trends at the heart of Revolutionary political culture—an orthodoxy now dominated by righteous Jacobinism. The lofty and principled moralism now in play sacrificed the playful, nudge-and-wink humor of much of the Old Regime production. It drew sustenance from the wider belief within Revolutionary culture of the virtues of denunciation of political treachery. Denunciation was a key issue in a political culture that was increasingly obsessed with fears of plots and conspiracies undermining Revolutionary probity.

After rising high in the Revolutionary firmament, Manuel crashed in the Terror. The gruesome September Massacres of 1792 put him increasingly at odds with most of his Jacobin peers, and though he voted for the king’s death, he resigned from the Convention and retired to his provincial home to await a certain rendezvous with the Revolutionary tribunal. He was guillotined in Paris on November 17, 1793. Yet Manuel’s influence lived on through the influence of his works. He had shown how the slander genre could adapt to a new political climate and how it could be refashioned into an even more toxic political tool. The post-1789 libelles helped to develop a taste for political calumny at the heart of Revolutionary culture—with highly damaging consequences.6

Through the work of Manuel and those like him, for example, public esteem for Louis XVI suffered far more from this new, humorless, patriotic literature of slander than it had prior to 1789. His queen was an even more egregious victim: Marie-Antoinette had been the fitful target of slander prior to 1789, but the police, using the kind of preemptive blackmail negotiations that Morande had pioneered, had kept the most unpleasant works from circulation. From 1789 onward, the queen’s reputation became a free-fire zone, with fatal consequences. The new form of slander was, Darnton wryly notes, the old stuff dressed up “in the latest patriotic drag.” But patriotic drag could make a deadly difference.

Darnton’s bravura demonstration of how Old Regime slander was grafted onto the main stem of Revolutionary political culture is one of the highlights of his engaging book. One may remain skeptical about whether the influence of the colorful and rather seedy characters who specialized in political slander was quite as great either before or after 1789 as Darnton claims. The libellistes seem to have been most effective when their work fitted in with wider political and ideological trends. But their writings certainly complicated and dramatized questions about the limits of free speech as it was used for personal vilification and innuendo. Those were questions with which the Revolutionaries wrestled and never resolved. And they are with us still, and not only in the blogosphere.

-

1

See especially Robert Darnton, “The High Enlightenment and the Low Life of Literature in Pre-Revolutionary France,” Past & Present, No. 51 (1971). ↩

-

2

See “[Finding a Lost Prince of Bohemia](/articles/archives/2008/apr/03/finding-a-lost-prince-of-bohemia/),” The New York Review, April 3, 2008. ↩

-

3

The Bohemians, translated by Vivian Folkenflik, with an introduction by Robert Darnton (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009). The French version, Les Bohémiens, is published by Mercure de France. ↩

-

4

A King’s Ransom: The Life of Théveneau de Morande, Blackmailer, Scandalmonger, and Master-Spy (London: Continuum, 2010). ↩

-

5

Robert Darnton, “[Blogging, Now and Then](/blogs/nyrblog/2010/mar/18/blogging-now-and-then/),” NYR blog, March 18, 2010. ↩

-

6

The theme is developed in Charles Walton’s recent Policing Public Opinion in the French Revolution: The Culture of Calumny and the Problem of Free Speech (Oxford University Press, 2009). ↩