1.

In 1993, in Los Angeles, a funeral was held for the word “def,” the old-school hip-hop term. Rick Rubin, the impresario who founded Def Jam Recordings in 1984 in his dorm room, presided. Al Sharpton delivered the eulogy. “Def was kidnapped by mainstream corporate entertainment and returned dead…. When we bury Def we bury the urge to conform.” Def’s disputed origins may in fact reside in the word “death” (as in “to death,” “done to death,” overdone). Etymology was, in this instance, destiny: the word was written on a slip of paper, placed in a breadbox-sized coffin, and lowered into the earth. It rests in the Hollywood Memorial Cemetery, near the graves of Peter Lorre and Douglas Fairbanks.

The show funeral for “def” suggests some of the funny ways hip-hop had evolved. Like many great inventions, hip-hop solved a problem people didn’t even realize they had. It turned out that people wanted to dance, uninterrupted, all night long. R&B, Motown, and reggae served as a pretty good score for these all-night parties, but there were some problems. You might think of a James Brown song like “I Feel Good.” The first problem is that it ends after only two minutes and forty-seven seconds. Whatever groove you get into dancing to it, it ends almost instantly. Problem two is that the really danceable part of the song—of any song—is the instrumental “break”—an even shorter interval.

Hip-hop, as invented by DJ Kool Herc in the West Bronx in 1973, found a way to expand the break infinitely: cue up two turntables, and when the break ends on one, play it on the other—repeat, repeat, repeat. Then mix it up: change one record, or both (“scratching” and other ways of making the turntables themselves instruments would come later). Everything followed from there: “breakdancing” was simply the kind of dancing you did to a potentially infinitely repeatable break. “Rapping,” or speaking in time to the beat, was possible, since, to use my example, James Brown’s spasmodic vocals had been cut.

But Herc and the other early stars (Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash among them) were slow to record. What they were making were not “songs”: they had no set duration, and they happened not in recording studios or even on concert stages, but in the basement rec rooms of housing projects and in the bombed-out lots of the Bronx. They were parties that unfolded as the score revved and slowed. Real purists would say that recorded hip-hop is by definition impossible. And so the rap “song” is an adaptation to commerce, which is why it shouldn’t surprise anyone that ways to make and spend money—by dealing drugs, by signing with a record label—became its folkloric core. The staged funeral for “def,” convened by Rubin, covered by MTV, and presided over by the foremost showman of solemnity, Al Sharpton, was an art of defiance of “mainstream commercial entertainment”—that was itself mainstream corporate entertainment.

It was a feat of inspired silliness for Rubin to blame the death of “def,” as he did, on its appearance in the dictionary. When the word turned up in dictionaries in 1993 (adjective: “cool”) Rubin was, he said, fed up. There is a special sort of absurdity in finding “living” dialect words entombed in the dictionary, and the absurdity compounds when the dialect was fashioned in the first place to defy standard English. Once “def” becomes a synonym for “cool,” it joins “cool,” along with “right on” and, later, “awesome,” “fly,” “phat,” “ill,” and “dope” on the pyre of outmoded slang. “Cool” once meant something quite specific in jazz: the more harmonic, more intellectualized (and whiter) West Coast sound of Dave Brubeck, as opposed to Charlie Parker’s expressivist bop. Now my four-year-old exclaims it dozens of times a day.

No popular entertainment has ever contributed so many expressions to the language in so short a time as rap, but by the time they hit the dictionary many are DOA. “Bling”—the brilliant corruption of “blink,” what diamonds seem to do when they sparkle—went out of fashion almost immediately after it was popularized in its current form by Lil Wayne in 1999. It was pronounced dead by MTV in 2003 (a very funny animated short by Matthew Vescovo traces its rise and fall1), around the time, that is, when people who don’t follow hip-hop first heard it. “Chill” as an adjective for being relaxed, composed (“I’m chill like that”), came and went in a blip after Digable Planets’ 1993 hit “Rebirth of Slick,” but not before it spawned “chillax” (an amalgam of “chill” and “relax”), which soon evolved into “chillax to the max.” (I first heard that phrase while visiting Deerfield Academy to give a poetry reading in 2002. Deerfield is not on hip-hop’s cutting edge.) Rap coinages spring up, fresh as daisies, only to be immediately plowed under: this ravenous newness is enforced by the anticipation of even newer expressions always on the horizon. And what is true for language is true for all hip-hop fashions, no sooner born than left for dead.

Advertisement

The improvised, eternally incomplete nature of hip-hop made it an abstract social space, transferable from neighborhood to neighborhood and nation to nation: the “lingua franca” of global youth, as Adam Bradley and Andrew DuBois argue in the introduction to The Anthology of Rap, their fine new book. This was a surprising destiny for an inscrutable culture that was once confined to a forbidding seven-square-mile area in New York City, with Crotona Park in the Bronx as its center. That circle rapidly dilated, taking in more and more of the East Coast, spreading to L.A., then—first via MTV and the major record labels, now YouTube and MySpace—across the world. Long ago it mythologized its own history, so that its distinct iconography, its outsized cast of thugs and naifs, and its inventory of boasts and taunts now play out over and over, often approaching farce.

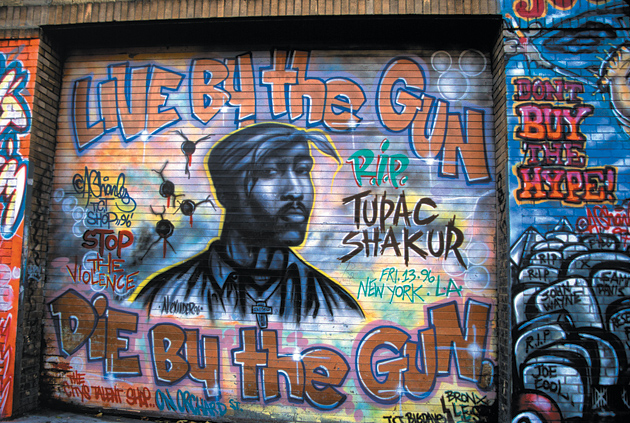

It became a game anyone could join; but to win, you had to prove you weren’t just anyone. You had to out- authenticate the other players. Thus the escalation of violence and meanness in rap lyrics and then (by the identical logic of out-authentication) in rappers’ lives. The show funeral Sharpton put on for “def” anticipated the central role in rap played by the high-profile funerals of its big stars, like Tupac Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G., the feuding gansta rappers gunned down six months apart in the Nineties. Gangsta rap made the threat of real violence one of its aesthetic criteria, not unlike the role overdose played in rock in the Sixties and suicide played in poetry of the early Seventies. One or two high-profile illicit deaths are enough to launch a thousand songs. When the white rapper Eminem wanted to prove his street cred, he showed off the scars he’d said he got in gang fights, growing up in Detroit.

As hip-hop widened and expanded, this fight over authenticity became a race to the hermeneutical bottom in which all contenders tried to act out in actual urban life their own symbolic self-presentations. When 50 Cent hit the scene, he claimed he had once survived nine gunshot wounds. (Doubts were later raised.) The battle for street cred threatened to crowd everything else out. The spectacle of “thug life,” with its cast of pimps, ho’s, and hustlers, attracted white audiences, who enjoy it when black people call one another names.

At the height of hip-hop’s popularity, something like 70 percent of its audience was white. And so the prophecy fulfilled itself, and rappers, catering to white audiences’ expectations that they embody the most prurient fantasies of blackness, started to play past each other, to the bored white teenagers looking on. (The spectacle of white kids listening to black rap is the subject of a fine book by Bakari Kitwana, Why White Kids Love Hip Hop: Wankstas, Wiggers, Wannabes, and the New Reality of Race in America.2)

In turn, some members of those white audiences, pointing to Eminem’s “struggle” for acceptance in an “all-black” industry (the vast majority of music executives are, of course, white), could claim to be uncannily included in rap’s narratives of oppression and marginality. You could even argue that being white, since it meant being a total outsider, was the most authentic imaginable position within rap. Only when white suburban kids started dressing and acting like the black caricatures drawn expressly for them did politicians enter the game. “Rap” itself became a symbol for urban criminality and deviance, and rejecting or refusing elements of it from an overall position of sympathy—as Bill Clinton did with Sister Souljah and Barack Obama did with Ludacris—worked potently as a political gesture.

Only in hip-hop is the age-old comedy of grown-ups trying to understand young people yoked so uncomfortably to the American tragedy of whites trying and failing to understand blacks. Age incomprehension is comic, since everyone young eventually grows old; race incomprehension is tragic, since nobody knows what it is like to change races. Growing up in Vermont, I met a total of one black person. I used to look with bemusement at the dictionary entry for “afro,” which included a helpful line drawing of a pleasant-looking black guy with a pile of hair on his head. That hairdo looked, to me, more bouffant than afro—but who was I to judge? This would have been around 1979, when the dictionary says “def” was born. Though I knew nobody with an actual afro, that illustration for “afro”—really, the very fact that the illustration was even in the dictionary—was clearly preposterous. Did people really have more of a need to see an illustration for “afro” than all the other words in that section? What about afreet or African violet?

Advertisement

We got cable TV in my house, which added only a handful of stations to the grand tally: one was an ABC affiliate out of Portland, Maine, which ran the identical shows as our local ABC channel. Another was a Montreal station that ran racy advertisements and gave me a sense of Europe. But the crown jewel was WPIX out of New York, which showed horror films, Yankees games called by Phil Rizzuto and Frank Messer, and, on the news every night, images of the South Bronx in flames. These three elements added up to my image of New York City, which nobody in my family had ever visited and which I didn’t visit myself until college. The cameras were trained on the flaming pyres where, before the Cross Bronx Expressway was built and the era of “benign neglect” of cities took over, real neighborhoods had thrived.

The news couldn’t see hip-hop, nor could Jimmy Carter the day his motorcade toured the Bronx, a precursor of George W. Bush’s Air Force One flight over New Orleans. If given the choice between traveling Transylvania to visit Dracula or walking through the South Bronx, I would absolutely have chosen the former. I was participating unwittingly in a discourse about hip-hop that continues today, whenever rap lyrics are introduced as evidence in criminal cases against young black men, or when Bill O’Reilly compares Ludacris (barely favorably) to Pol Pot.

2.

The Anthology of Rap is among the best books of its kind ever published. But what kind of book is it? It is not an anthology of poetry: whatever their formal brilliance, their agitated verbal ingenuity, raps are not exactly poems. They are also not exactly song lyrics: there’s no melody to miss (and to supply mentally) as with printed lyrics by, say, Irving Berlin. Banish from your mind the tune to “Puttin’ on the Ritz,” and simply read these lyrics as lines of poetry:

Now, if you’re blue

And you don’t know where to go to

Why don’t you go where fashion sits

Puttin’ on the ritz

Different types who wear a daycoat

Pants with stripes and cutaway coat

Perfect fits

Puttin’ on the ritz

Without the tune, you would never know that the rest before the refrain—the phrase “puttin’ on the ritz”—is the same duration in both instances: “why don’t you go where fashion sits” is a full four-beat line of poetry, while “perfect fits” is a two-beat half line. You would expect to wait longer for the refrain in the latter case, but in most versions of the song, you don’t. In fact, one brilliance of the song is in that uniform transformative silence—sufficient time (symbolically) to change clothes, change moods, and, the song suggests, change destinies. That rest has to be the same duration in every case: one, two—“Puttin’ on the Ritz.” It is the “abracadabra” portal through which ordinary dreary shlumps pass and become Fred Astaire. It’s not there on the page.

Rap is uniquely independent of tune. Most rap works still within the “four-on-the-floor” beat favored by the early MCs like Melle Mel and Spoonie Gee, whose style derives (as Henry Louis Gates suggests in his foreword to this book) from the Jamaican-derived “toast” and African-American “rhetorical games” like signifying and playing the dozens. You can hear it—and get a sense, however partial, of what the record sounds like—reading this passage from the Eighties group the Cold Crush Brothers:

What’s up, fly guys? Hello, fly girls

It’s the big throw-down at Harlem World

The Cold Crush Four versus Fantastic Five

They ain’t no comp, we’ll eat ’em alive

These “throw downs,” or con- tests, happen across neighborhoods whose distinct styles made them feel, in those days, like different planets (“Harlem World” vs. “Planet Rock,” a name for the Bronx). But they happen across time, as later rappers work inside the identical meter. This is tetrameter—four beats across the line—but the rhythm varies from line to line. The first line is regular iambic (one-TWO, one-TWO), the grid against which every subsequent improvisation plays out. The second line sneaks in more syllables before the first beat: one-two-THREE, one-TWO, one-TWO, one-TWO. The third line starts out iambic for the first two feet, then becomes anapestic—one-two-THREE—for the second two feet. Line four returns to straight iambs, with the exception of the anapestic final foot. The fewer the syllables in a given four-beat line, the slower, the more emphatic, the rap. You can hear it simply by reading it.

Later rap takes rhythmic variation within the standard four-beat line to acrobatic lengths. This is a pair of lines about a “middleman” who was killed by mistake from Big Pun’s “Twinz (Deep Cover ’98)”:

Dead in the middle of little Italy

Little did we know that we riddled a middleman who didn’t do diddly

The juggernaut of syllables driving toward every stress—one-two-three-FOUR, one-two-three-FOUR, one-two- three-four-five-six-SEVEN—make you actively crave the beat, which Big Pun defers almost excruciatingly by his barrage of little unstressed words. As a result, extraordinary linguistic pressure builds up behind every stress, like water threatening to breach the hull of a submarine.

In its tunelessness, rap is at the opposite end of the spectrum from rock. In rock, the lyrics are often unintelligible (this is every suburban parent’s ur-complaint about rock: “I can’t understand what he’s saying!”), often deliberately so, as with some of Mick Jagger’s singing, or Michael Stipe’s on the early records of R.E.M. The damaged or partial intelligibility of the lyrics produces some of rock’s important effects of encryption and doublespeak. When, on “Honky Tonk Women,” Jagger sings the lyrics “I played a divorcee in New York City,” it sounds more like “Later [or perhaps “I laid her”], dear folks say in New York City.” There is a long tradition of mistaking Jimi Hendrix’s lyric “‘Scuse me, while I kiss the sky” for “‘Scuse me, while I kiss this guy.” The examples abound: for important historical reasons (radio censors, parents, Fifties mores) rock lyrics are often tantalizingly hard to pick out. Whether in the shrieks and wails of Robert Plant or the mumbles and murmurs of Lou Reed, rock, like opera, often presents the voice as simply the lead instrument.

It makes wit, and wit’s primary vehicle, the surprising or inventive rhyme, largely absent from rock. Rock still rhymes within the simplified pairings of the blues (“You need coolin’/Baby I’m not foolin’/I’m gonna send you/Back to schoolin'”—Led Zeppelin). It behaves often as though some binding edict against wit were handed down at its founding. But rap is more like the American Songbook in its primal appetite for rhyme. Its rhymes, like all rhymes, act as a way of registering what Emily Dickinson called “internal difference,/Where the Meanings, are.” Sometimes those differences are revelatory: “survival” and “Bible” (that’s Darwinism vs. Creationism, in a nutshell), or, later in the same rap, “Pocahontas” and “Nostradamus” (both are guides into the unknown). But rap rhymes everything, and rhymes lawlessly, as a form of pure bravura often marked as such, as in Freestyle Fellowship’s “Can You Find the Level of Difficulty in This?”:

You’re in a sticky situation zero visibility late night radar emergency

Passenger planet typhoon hurricane broken components

Airstrip stormy rain military ship landing a plane in Malaysia amnesia

Indonesia with a squeegee, you were trying to make a dollar out of fifteen cents

Cole Porter at his most manic offered, still, a vision of culture that allowed for the leisurely survey of all language, arrayed upon a giant buffet, for the discriminating connoisseur to choose a most succulent rhyme. The lines I’ve quoted rhyme as death- defying spectacle, with every B-movie contrivance thrown in to up the ante, from amnesia to squeegees to (a little later) Fiji to the Bee Gees.

Rap’s swaggering lawlessness depends, paradoxically, on its total subservience to rhyme and to 4/4 time. This rigidity of form reminds people of poetry, though, to be sure, not any poetry any poet of note has written in at least fifty years. When Porter’s lyrics were published several years ago by the Library of America, the inevitable question—are they poetry?—immediately arose. A great case has been made by a great critic (Christopher Ricks) that a great lyricist—Bob Dylan—is, in fact, a poet. (Dylan famously demurred from the title, calling himself a “song-and-dance man.”) When I read Ricks’s classic Dylan’s Visions of Sin I was convinced that if Dylan was in fact a poet (in the sense that Tennyson and Keats are poets), it was only owing to Ricks’s brilliant midwifery. And I love Dylan immoderately, as I love Cole Porter. Maybe the wisest statement on song lyrics and poetry was Robert Gottlieb’s in his introduction to Reading Lyrics

3: “As everyone understands, reading lyrics is different from reading poems.”

The problem is that no two people who use the word “poetry” mean the same thing anymore. What would not be good (and there is some evidence that this is already happening) is to replace poetry—the standard everyone was trying to live up to in the first place, the Sappho-to-Plath line that shed instrumental accompaniment aeons ago—with Porter, or Dylan, or rap, in the classroom. It is one thing for Bradley and DuBois, Harvard Ph.D.s who have read Hardy and Hughes, Keats and Komunyakaa, to read rap lyrics as poetry. It is another thing for a high school kid to pick this book up and decide that rap (or Porter or Dylan) represents the best that has been thought and said.

It is also a little disingenuous to suggest (as Bradley does in his otherwise excellent Book of Rhymes

4) that the popularity of rap proves that “by rejecting metrical patterns and often rhyme as well, literary poetry has lost a good share of its popular appeal.” I’m not sure poetry has lost much of its popular appeal, and anyway, most popular poets—Billy Collins, Mary Oliver, Jewel, Jimmy Carter, Pope John Paul II, Charles Bukowski—usually don’t rhyme. But if you look at a poet like Paul Muldoon (who plays in a rock band, and has written many poems in the manner of Cole Porter’s lyrics), you see a fully literary poet doing rhyme and meter with nearly viral proficiency, rather in the manner of—or at the pace of—rap. Bradley’s probably right: contemporary poetry has been quarantined from rhyme and meter for too long.

3.

The Anthology of Rap is remarkable for refocusing our attention on the art of rap, even as it proves that rap’s artistry is inextricable from the arguments that surround it. “Battles”—contests between MCs or dancers—were once the essence of hip-hop; when battles turned nasty, they became beefs, and many fans date the death of hip-hop from the moment beefs eclipsed battles (beefs sometimes end violently; battles never do). At a certain point, though, battles about beefs took over much of hip-hop, and this meta-sparring over the nature of the art marked hip-hop’s mannerist phase. The era of active beefs, as well as much of the violence, seems to be over. But the stories are well known: Biggie vs. Tupac, Bad Boy vs. Death Row, East Coast vs. West Coast. With rap, argument has a way of always turning into self-conscious spectacle. It then becomes infinitely sellable, and rappers, bound to the wheel of commerce by their very defiance of it, have a choice: ignore the problem or rap about it.

The canon has now coalesced; the music is no longer a contested zone. The best raps of the last fifteen or so years sell—in both the intransitive and the transitive senses: they sell themselves, but they also sell cars, clothes, accessories, everything. Jay-Z’s raps mock the “big business” of rap and, a few verses later, boast about his “Rock-a-Fella” label and Rocawear line of clothes. His memoir, a lavish affair with glossy images, was published this fall.5 He was received warmly at the New York Public Library, in an event moderated by Cornel West. Even as rap undermines its whole demented code of money, cars, ho’s, and hustlers, it markets it, markets itself. (This dynamic was identified by Kelefa Sanneh in a now-classic New Yorker piece on Jay-Z.) It makes rap in some ways the savviest and wittiest critique of the business of art ever conducted from inside of artworks, but the critique doesn’t undermine the business: it is the business. You have to go back to Juvenal or Pope to find anything this scathing and self-promoting in poetry. And if we think of other highly profitable contemporary forms of art—films, novels, visual arts—how many of them acknowledge the absurdity of their economic position with anywhere near the intelligence and vitality of Jay-Z’s “Renegade,” which includes this cameo by Eminem?

Now who’s the king of these rude ludicrous lucrative lyrics

Who could inherit the title, put the youth in hysterics

Usin his music to steer it, sharin his views and his merits

But there’s a huge interference—they’re sayin you shouldn’t hear it

Maybe it’s hatred I spew, maybe it’s food for the spirit

Maybe it’s beautiful music I made for you to just cherish

But I’m debated, disputed, hated, and viewed in America

As a motherfuckin drug addict—like you didn’t experiment?

“Ludicrous lucrative” is an amazing phrase: the omitted conjunction between the two words turns the second word, “lucrative,” into a partial revision of the first, “ludicrous,” as though they were near synonyms. Which, of course, in this context, they are. This confluence of the risible and the profitable makes the subsequent inventory of condemnations of rap (it drives kids crazy, it spreads “hatred”) and the defenses of it (it is “beautiful,” uplifting to the “spirit,” even heartfelt) meaningless. But it doesn’t make this song, which rifles through all the overfamiliar arguments for rap, pro and con, allowing each one only the nanosecond it deserves, meaningless. Rap is where the disputes about rap are rapped about.

Rappers have now been rapping for years about the death of rap. Nas’s big-selling 2006 record “Hip Hop Is Dead” gives a sense of the current morbid state of the art. The best writer on rap, Tricia Rose of Brown University, begins her recent book The Hip Hop Wars with this bleak assessment:

Hip hop is not dead, but it is gravely ill. The beauty and force of hip hop have been squeezed out, wrung nearly dry by the compounding factors of commercialism, distorted racial and sexual fantasy, oppression, and alienation.6

If life in an art form is measured by its capacity to surprise us without resorting to shocking us, rap would seem to be a thing of the past. There are now definitive histories of hip-hop (Jeffrey Chang’s Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop is excellent), urban dictionaries of every variety, fine scholarly books (Rose’s Black Noise, Michael Jeffries’s forthcoming Thug Life), and this anthology—all signs that the era of rap has slowed and started to coalesce into a mere historical fact.

But historical facts have their uses. Our president, a youngish black man who has Lil Wayne on his iPod, sounds great when he uses phrases—“bring it,” “you got game”—cribbed from hip-hop. There are dozens of rap hits about Obama (among other things, his name is a lot of fun to rhyme). You could argue that they had a significant part in electing the President—will-i-am’s “Yes We Can” certainly did. Did rap die, or did it simply win?

This Issue

January 13, 2011