Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera

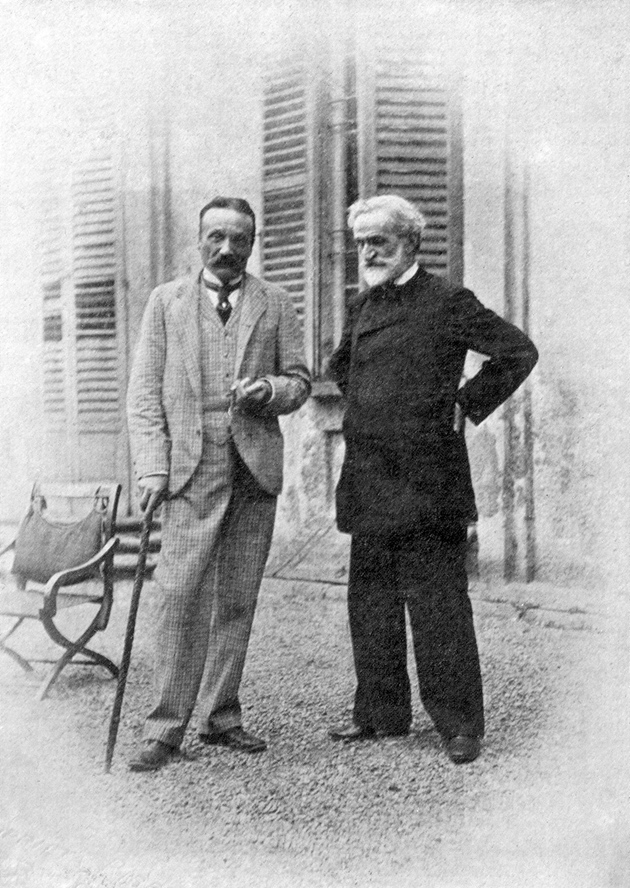

Barbara Frittoli as Maria Boccanegra, Dmitri Hvorostovsky as Simon Boccanegra, and Roberto De Biasio as Gabriele Adorno in the final scene of Giuseppe Verdi’s Simon Boccanegra at the Metropolitan Opera, January 2011. The original version of the opera was premiered in 1857 and was not a success; Arrigo Boito’s first collaboration with Verdi was his revision of the libretto for a new version, which was first performed in 1881.

Verdi had a great advantage over Rossini’s Otello (1816) in composing his own Otello (1887). It was an advantage, even, over his earlier Shakespearean opera, Macbeth (1847). Verdi had as his librettist, by the 1880s, Arrigo Boito, a highly cultured poet and musician, a man as serious about getting to the true meaning of Shakespeare as was Verdi himself. Besides the two works Boito created with Verdi (Otello and Falstaff), he wrote a libretto for Amleto (Hamlet), composed by his friend and fellow musician Franco Faccio. He also translated and condensed Antony and Cleopatra for performance by his lover, the great Italian actress Eleonora Duse.

The later collaboration between Verdi and Boito could not have been expected from their early contacts, which had created enmity between them. Boito came from a talented and aristocratic family. His father, Silvestro, painted miniatures of Pope Gregory XVI in the Vatican. His mother was a Polish countess. His older brother Camillo, an architect, historian, and novelist, was for forty-eight years a professor of architecture at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan.

Arrigo shared his brother’s wide culture and high aspirations as a theorist of the arts. Early on, the brothers were Scapigliati (“The Rumpled”), members of the Milan circle of young writers, painters, and musicians who scoffed at older Italian styles (including that of Verdi). The Scapigliati enjoyed a radical lifestyle, idolizing Baudelaire, communing over hashish and absinthe. Some of them, including their best-known poet, Emilio Praga, died young of alcoholism or suicide. One of the Scapigliati, Giuseppe Giacosa, drew on his young artistic days when he cowrote the libretto for Puccini’s La Bohème. Clarina Maffei, who had the most famous and influential salon in Milan, welcomed the Scapigliati to her home, in what Tom Wolfe would later call an exercise in radical chic. This got her, temporarily, into trouble with her old friend Verdi.

Verdi had been close to Clarina’s ex-husband, Andrea, who had helped him with Francesco Maria Piave’s libretto for Macbeth. In 1862, drawing on her extensive Parisian connections, Clarina suggested to Verdi, who was in Paris, that he get a text for his Inno delle Nazioni (Hymn of the Nations, to be sung at the International Exhibition in London) from the twenty-year-old Boito, who had just arrived in Paris. Verdi knew nothing of Boito at the time, but he was in a hurry to get the irksome London commission off his hands, so he accepted her suggestion. Only later did he become aware of what he considered the disturbing views of the Scapigliati, which made him deeply hostile to them.

Boito and Franco Faccio, as students at the Milan Conservatory, conceived the ambition of remaking Italian music, taking their inspiration from the north, from Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer and Wagner. They condemned the Italian opera of their day as more interested in formulas than in form. They collaborated at the conservatory on two patriotic cantatas, Il Quattro Giugno (The Fourth of June, 1860) and Le Sorelle d’Italia (The Sisters of Italy, 1861). They graduated with prize money for travel abroad, which took Boito to Paris and the composition of Verdi’s Inno. Back in Italy, Franco Faccio composed his first opera, I Profughi Fiamminghi (The Flemish Refugees), to a libretto by Emilio Praga, which received its debut at La Scala in 1863, when Faccio was only twenty-three. At a banquet honoring this event, Boito read a boastful ode to his promising schoolmate, “All’Arte Italiana.” It contained lines that earned an ill fame:

He may already be born

who will raise again an art,

chaste and severe, on the altar

slimed like a brothel wall.

Unfortunately for all concerned, this brash poem was gossiped about and printed in the Museo di Famiglia, where Verdi read it and took it as an insult to his own body of work. In a sarcastic letter to his publisher, Tito Ricordi, he wrote: “If among others I, too, have soiled the altar, as Boito says, let him clean it, and I will be the first to light a little candle.” Over and over, for years, Verdi bitterly recalled the “slimed altar” line in his letters. As Frank Walker writes in The Man Verdi, “Was there ever a composer so sensitive to criticism, so tenacious in rancor?” It did not help that Boito’s music teacher and patron was Alberto Mazzucato, then the principal conductor at La Scala, whom Verdi despised.

Advertisement

When Clarina Maffei persisted in promoting her young friends to Verdi, he broke off relations with her, and his wife had to scan incoming letters to intercept those that would anger him by praising the young upstarts. Meanwhile, the upstarts kept starting up. In 1865, Faccio premiered his second opera, Amleto, to Boito’s libretto from Shakespeare. The same year, Boito and Praga launched their critical journal, Il Figaro, and Boito and Faccio joined Garibaldi’s guerrilla fighters against the Austrians. In 1868, Boito conducted at La Scala the premiere of Mefistofele, for which he had been both librettist and composer. It was a disastrous failure. Only seven years later, in a radically altered form, did it achieve success at Bologna.

Faccio, meanwhile, had given up composing after the failure of his revised Amleto in 1871. He concentrated on conducting, since he was meeting with particular success at leading Verdi operas in Germany and Scandinavia—so much so that a softened Verdi chose him to conduct the Italian premiere of Aida in 1872. Boito, too, was doing less composing, though he continued to work, with dogged disappointment, on his second opera—never finished—Nerone. He continued to write librettos for other composers—for Coronaro’s Un Tramonto (1873), Catalani’s La Falce (1875), Ponchielli’s La Gioconda (1876), San Germano’s Semira (withdrawn in rehearsal), Bottesini’s Ero e Leandro (1879), Carlos Gomes’s Maria Tudor (1879, finishing a libretto begun by his late colleague Emilio Praga), Pick-Mangiagalli’s Basi e Bote (1887, though not performed till 1927), Dominicetti’s Iram (not composed).

But the life-changing work on which Boito’s fame would rest began in 1879, when Giulio Ricordi got Verdi to start considering, slowly, a collaboration with Boito on Otello. Before that project could be truly launched, there was a trial run as Boito revised the libretto of Verdi’s 1857 opera, Simon Boccanegra. The surviving Scapigliati, who had shed their youthful cheekiness, had gradually been joining the ranks of Verdi admirers. Ricordi, who was the same age as Boito and Faccio, had been a young musical theorist in their circle, but as he grew older he took on the responsibilities of his father Tito’s publishing house and became a trusted business adviser to Verdi. He worked with Verdi’s ever-diplomatic wife, Giuseppina, to coax him into looking at Boito’s libretto for Otello (at this stage called Jago). Mutual respect grew in the men as they worked together on Simon Boccanegra.

Simon had not been a success at its premiere, but it has rich music and resonant political themes, and Verdi hoped to salvage the best parts of it. Ricordi kept urging him to revise it, though Verdi thought that Aida and the Requiem Mass would be his crowning (and final) works. He had grown to hate the endless battles that were involved in getting the right singers, conductors, and productions for his ever-more-demanding works. But Boito brought fresh eyes to the subject of Simon Boccanegra. He argued that the characters had to become more “living,” that there should be a dramatic Council Scene, and that the action should be more comprehensible. Verdi resisted sinking too much energy into large revisions, but Boito cajoled and suggested, reinvigorating the maestro’s creative force. The revised work, conducted by Faccio at La Scala, was a success in 1881. Victor Maurel (the future Jago) sang the role of Boccanegra, Francesco Tamagno (the future Otello) that of Gabriele Adorno. Thus was assembled the team (Verdi, Boito, Ricordi, Faccio, Maurel, Tamagno) that would triumph, six years later, at the premiere of Otello.

Verdi and Boito grew in affection for each other over the years of their collaboration. Verdi at first would not even let Ricordi bring Boito to visit him, since he feared a commitment to new work. But composer and librettist soon came to love and seek each other’s company. In 1885, Boito was still writing him: “My desire to see you is great, but the fear I have of disturbing you is equally great.” Verdi answered: “You could never disturb us! Come, and you will give great pleasure to me and to Peppina, too.”

Nonetheless, dealing with Verdi was always a ticklish prospect. Anything could make him shy from a major undertaking in his seventies. When Boito’s Mefistofele received a successful Naples production in 1884, he was given a celebratory banquet at which he spoke with enthusiasm about the Otello libretto he was working on. The newspaper Il Piccolo interpreted his words to mean that he wished he could compose the opera himself. Verdi read another report of the banquet in the Neapolitan paper Il Pungolo, and fired off a letter to Franco Faccio:

I address myself to you, Boito’s oldest, most steadfast friend, so that upon his return to Milan you may tell him in person, not in writing, that—without the shadow of resentment, without any deep-seated anger—I return his manuscript to him intact. Furthermore, since the libretto is my property, I offer it to him as a gift, for whenever he intends to compose it. If he accepts this I will be happy—happy in the hope of having furthered and served the art we all love.

Faccio responded instantly that Boito had been misunderstood, and expressed “what he [Boito], Ricordi, I, and all who love and long for the glory of Italian art would feel if you really were to resolve not to write Otello.” Boito, when he heard what Verdi had written to Faccio, was shattered. He wrote a long and emotional letter telling Verdi he had no wish to compose anything but his elusive Nerone, and no greater desire than this:

Advertisement

To have you set to music a libretto that I have written solely for the joy of seeing you take up your pen once more per causa mia, for the glory of being your collaborator, for the ambition of hearing my name coupled with yours, and ours with Shakespeare’s, and because this theme and my libretto have been transferred to you by the sacred right of conquest. Only you can compose Otello. The entire world of opera you have given us affirms this truth; if I have been able to perceive the Shakespearean tragedy’s enormous capability of being set to music (which I did not feel at first), and if in fact I have been able to prove this with my libretto, it is because I placed myself within the sphere of Verdian art. It is so because, in writing those verses, I felt what you would feel when illustrating them with that other language—a thousand times more intimate and mighty—sound. And if I have done this it is because I wanted to take the opportunity in the prime of my life, at an age when faith no longer wavers, to take the opportunity to show you, better than by praises thrown in your direction, how much I love and am moved by the art that you have given us…. For Heaven’s sake don’t abandon Otello, don’t abandon it. It is predestined for you.

Then, in a shrewd stroke, to whet Verdi’s appetite for the work, he sent off a new text for what he and Verdi had already discussed—an “evil Credo” for Jago. Verdi showed he was back on board when he wrote: “This Credo is most beautiful, most powerful, and Shakespearean in every way.”

Work on the librettos of Otello and Falstaff was a true collaboration. Verdi made structural suggestions as well as textual corrections to the libretto, and Boito prompted Verdi to new musical thoughts, especially in the handling of Falstaff’s source, The Merry Wives of Windsor. They developed a fondly bantering way of trading ideas, far from the exasperated and hectoring tone Verdi used when dealing with the limits of earlier, less competent librettists. Since Verdi wanted to keep his projects secret, they used a code, calling Otello “Il Cioccolato” (the Chocolate) and Falstaff “Pancione” (Megabelly).

Though Verdi had had to be edged ever so gently into work on Otello, he responded with glee to the idea of working again with Boito on another Shakespeare play. He had not written a comic work since the failure of his second opera, Un Giorno di Regno, in 1840. Boito told him: “There is only one way to end better than with Otello, and that is to end victoriously with Falstaff.” Verdi felt the same. Asking for a sound argument for working at his age, he wrote Boito: “If you could find a single reason, and if I knew how to shrug ten years off my shoulders, then…What joy! Being able to tell the public: We are still here!! Make way for us!!” Boito not only wrote the librettos for the two operas, but engaged energetically in the casting and production details of each, working with his friend Faccio in the preparation of Otello at La Scala.

The two men’s jocular tone over Il Cioccolato became an almost giddy way of referring to Pancione in their letters. Boito wrote:

I live with the immense Sir John, with Pancione, with the breaker of beds, with the smasher of chairs, with the mule-driver, with the bottle of sweet wine, with the lively glutton, between the barrels of Xeres and the merriment of that warm kitchen at the Garter Inn.

If Verdi’s composing efforts slowed, it was said that Pancione was loafing or sleeping or drunk. Or Falstaff was pining away for lack of sustenance: “Poor fellow! Since that illness which lasted 4 months he is scrawny, scrawny! Let’s hope to find some good capon to reinflate his belly…. It all depends on the doctor!… Who knows! Who knows!” If the tempo of work picked up, Falstaff was on a tear:

Pancione is on the road that leads to madness. There are days when he doesn’t move, sleeps, and is in a bad mood. At other times he shouts, runs, jumps, rages like the devil…. I let him sober up a bit, but if he persists, I’ll put a muzzle and a straitjacket on him.

Boito was so heartened by this good news of progress that he wrote back ebulliently:

Evviva! Let him have his way, let him run, he will break all the windows and every piece of furniture in your room; never mind, you will buy others. He will smash the piano, never mind. You’ll buy another one; let everything be turned upside down! But the big scene will be done! Evviva!

Go! Go! Go! Go!

What pandemonium!!

But pandemonium as bright as the sun and dizzying as a madhouse!!

I know already what you will do. Evviva!

In each of their two operas, Verdi and Boito faced a point that stumped and stalled them—the concertato end of Act Three in Otello and the whole of Act Three in Falstaff. They circled the problems, worrying them, chipping at them with new and overlapping suggestions, until they were solved, triumphantly. In old age Boito remembered the two decades of his close and continuous work with Verdi as the high point of his life. Those were also his years of romantic ardor for Eleonora Duse (1887–1892). There was enough of the Scapiglatura of his youth for Boito to have a nostalgie de la boue toward Duse’s shoddy theatrical past. She had acted from childhood in provincial melodramas that he thought unworthy of her. He kept his affair with her secret while he tried to improve her tastes and coach her in the classics, hoping she would equal her older French rival, Sarah Bernhardt. Despite Duse’s later famous affair with Gabriele d’Annunzio, she considered her involvement with Boito the most elevating and spiritually rewarding interlude in her life.

Boito translated Antony and Cleopatra for Duse, but did not attend the rehearsals or the premiere of his play, at a time when he was involved in every detail of the rehearsing and premieres of the Verdi operas. He did not want to bring the stage waif Duse, twenty years his junior, into the aristocratic milieu of Clarina Maffei, or into Verdi’s exalted circle. He resisted a lasting commitment to her and to the idea of raising her daughter from an unhappy early marriage. Indeed, he never married anyone, though, against Verdi’s initial doubts, he insisted that Falstaff had to end with a double marriage scene: “There have to be nuptials; without the weddings there is no contentment (don’t mention this to Signora Giuseppina; she would start again to talk to me about matrimony!) and Fenton and Nannetta must marry.”

Boito and Verdi were brought closer than ever by the tragic end of their shared friend Franco Faccio, which interrupted for a time their work on Falstaff. Tertiary syphilis was destroying Faccio’s mind. He would not repeat his conducting feat for Otello when Falstaff was completed. In 1889, when he was no longer able to manage La Scala’s affairs, Boito and Verdi arranged for him to be employed as director of the Parma Conservatory. When Faccio could not meet even his minimal tasks in Parma, Boito filled in for him so that Faccio could continue to be paid his salary. Boito had sent his friend to the Krafft-Ebing center for syphilis treatment in Graz, but the doctors there said there was nothing they could do for him. Verdi commiserated with Boito: “The refusal in Gratz, I think, is grave! It’s a condemnation!… Poor friend! So good and so honest!” Boito wrote to Duse: “My sick friend has returned, in worse shape. There is no more hope. It is frightful to see him. I am spending my days, all my hours, at his side.” Boito was at Faccio’s bedside when he died in 1891. The famous conductor was only fifty-one. Verdi wrote to console Boito. The old opponents of the Scapigliati days had now become as close as brothers:

Poor Faccio was your schoolmate, companion, and friend in the stormy and happy times of your youth….(And he loved you so much!)—In the great misfortune that struck him, you rushed to him, giving him solemn, admirable proofs of your active friendship…. Poor unfortunate Faccio!”

Boito and Verdi rallied from their shared sorrow to finish and produce Falstaff in 1893. Boito was loath to let their partnership end at that point. Though Verdi was now in his eighties, Boito kept suggesting new projects to him. He said he could adapt his translation of Antony and Cleopatra, done for Duse, into a libretto for Verdi to set as an opera. He even tried to revive Verdi’s long interest in composing a King Lear. But this time Verdi’s wife was no longer conspiring with him for new projects. She wrote: “Verdi is too old, too tired.”

The most Boito could do for new work from Verdi was to promote a first publication of his Quattro Pezzi Sacri (Four Sacred Pieces), already written. In 1898, Boito, who had played a leading role in getting Otello and Falstaff translated and performed in Paris, presented three of the four Sacred Pieces in a successful premiere at the Paris Opera. (The Ave Maria was omitted, at Verdi’s request.) Though Verdi, as usual, paid close attention to the proper casting and performance of the work, he did not feel well enough, at eighty-five, to go to the opening himself. He wrote to Boito:

In going to Paris in my place you have rendered me a service for which I shall always be grateful. But if you reject any form of recognition I remain crushed by a burden I cannot and ought not to support. Well then, my dear Boito, let’s talk frankly, without reticence, like the true friends we are.

To show my gratitude, I could offer you some trifle or other, but what use would it be? It would be embarrassing for me, and useless to you.

Permit me therefore, when you are back from Paris, to clasp your hand here. And for this handclasp you will not say a word, not even “Thank you.” Further, absolute silence on the present letter. Amen. So be it. Affectionately, G. Verdi

In the later years of Verdi’s life, Boito visited him often, at his home, or in Genoa, or in Milan. He usually spent Christmas and Easter with him and Giuseppina—and after the latter’s death in 1897, he was even more constant in attendance on her husband. When Verdi died, in 1901, Boito wrote to his French friend, Camille Bellaigue:

I threw myself into my work, as if into the sea, to save myself, to enter into another element, to reach I know not what shore or to be engulfed with my burden in exertions (pity me, my dear friend) too great for my limited prowess.

Boito lived until 1918, and never finished his Nerone. He felt the real distinction in his life lay in his collaboration with Verdi: “The voluntary servitude I consecrated to that just, most noble and truly great man is the act of my life that gives me most satisfaction.”

There have been other great collaborations between librettists and composers in the opera world—Da Ponte with Mozart, Hofmannsthal with Strauss, Auden with Stravinsky. But none worked more closely together, with deeper understanding of each other’s needs and merits, than Boito and Verdi. Verdi constantly urged Boito not to neglect his own opera, Nerone (whose libretto he had read and admired), while working on their joint ventures. Boito understood music, and Verdi understood drama, and each spurred the other to achieve greater things than they had ever done alone.

Theirs was an empathy that erased the three-decade difference in their age. Despite his own superior education, Boito never underestimated the lightning intelligence of Verdi. Typical of their many discussions is Verdi’s request to know how the English accent words like Falstaff or Windsor or Norfolk. Boito responded that they accent the first syllable in two-syllable proper names, though he admits that meter made him accent the last syllable of Norfolk in Falstaff’s song “Quando ero paggio.”1 Thousands of little con- siderations like this went into their years of weighing each word and each note in these colossal scores.2

Frank Walker, the modern critic who made the English-speaking world appreciate the importance of Boito, paid him this tribute:

It was fortunate for us, and for Verdi, that among the younger generation there was this companion, so subtly intelligent, so unselfishly devoted. The more one learns of Boito the more he appears one of the noblest and purest spirits of the whole romantic movement.

Verdi knew what Boito had done for him. After the successful premiere of Otello, and then again after that of Falstaff, he led Boito out with him to take the multiple curtain calls they had earned together.

This Issue

March 24, 2011

-

1

Boito was forgetting Scottish names like Macbeth and Macduff. ↩

-

2

In a less intense collaboration, Auden said that he worried that Stravinsky had never set an English text when they worked on A Rake’s Progress. But when the composer mistook the accent on sedan chair (stressing the first syllable of sedan), he quickly corrected himself when the error was pointed out. W.H. Auden, Forewords and Afterwords, selected by Edward Mendelson (Random House, 1973), p. 433. ↩