The only successful coup d’état in American history occurred on November 10, 1898, in Wilmington, North Carolina. At the time, the city was one of the most prosperous ports on the East Coast and a center of African- American economic and political power. The local government had been controlled by Democrats for two decades, but that changed in 1894 and 1896 when black voters, now a majority of the citizens, elected a coalition of Republicans and Populists. The city’s white aristocracy would not stand for it.

“We will never surrender to a ragged raffle of Negroes,” declared one of their leaders, a former congressman and Confederate colonel named Alfred Moore Waddell. “Even if we have to choke the Cape Fear River with carcasses.”

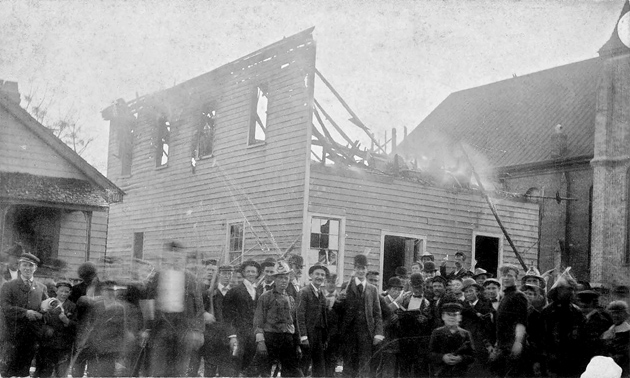

On the morning of the 10th as many as two thousand white men and boys took to the streets, armed with rifles, pistols, and rapid-fire Colt machine guns mounted on horse-drawn wagons. They began by burning down the offices of The Daily Record, the city’s black newspaper. In photographs taken afterward, the men pose in front of the incinerated building with their shotguns raised. The second floor has been reduced to a single wall, the smoke billowing from its splintered planks. Grinning boys stand in the front row, cradling their smaller guns. (See illustration on page 42.)

The mob proceeded to the neighborhood of Brooklyn, the heart of Wilmington’s African-American community, where they slaughtered what men they could find. Some of the revolutionaries—for that’s how they saw themselves, having issued a “White Declaration of Independence”—boarded streetcars and fired into the windows of homes and businesses as they passed by. Corpses began to collect in the streets. In the midst of this tumult, the revolution’s leaders stormed City Hall. At gunpoint, they forced the mayor and his board of aldermen to resign, and installed their own government. Colonel Waddell became mayor. It’s not known for certain how many people died in Wilmington that day—the estimates range well into the hundreds—but eyewitnesses claimed that the Cape Fear did in fact run red with blood.

The city’s African-American businessmen and political leaders were stripped of their possessions and marched to the station, where they boarded trains headed north. The new administration moved quickly to fulfill the points of their Declaration of Independence, chief among them the revocation of black suffrage and the transfer of jobs from blacks to whites.

Despite numerous conflicting reports at the time, the most widely accepted account of the massacre was Colonel Waddell’s. In “The Story of the Wilmington, NC, Race Riots,” published two weeks later in Collier’s Weekly, Waddell described the burning of the Record’s office as “purely accidental” and suggested that the violence was incited by black politicians. It was not until 2005 that a historical commission, created by the North Carolina legislature, conducted a comprehensive investigation into what happened in Wilmington in 1898, and why. In 2007 the North Carolina Senate passed a resolution expressing “profound regret that violence, intimidation and force” were used to overthrow a municipal government. The North Carolina Senate that year also apologized for slavery.

The atrocity in Wilmington lies at the heart of A Moment in the Sun, John Sayles’s sixth book of fiction. It is a natural subject for him. In his novels and his twenty films, Sayles has proved himself a connoisseur of American shame. He has found his theme in the exploitation of West Virginia miners in the 1920s (Matewan), the 1919 Black Sox Scandal (Eight Men Out), electoral politics (Silver City), the Bay of Pigs (his previous novel, Los Gusanos), and rapacious real estate developers in Florida (Sunshine State) and New Jersey (City of Hope).

The shame is all on the side of the land developer, the coal executive, the greedy baseball team owner. The exploited working stiff, whose fate is tied to complex historical and political machinations far out of his control, is our hero—along with his friends, family, and coworkers. Sayles has an affinity for large crowds of characters. As a film director, his affection for ensemble acting bears some relation to Robert Altman’s approach, the biggest difference being that Sayles gives each of his characters plenty of time to speak their piece without interruption. And speak they do. In Sayles’s films and novels, there is often an uneasy tension between storytelling and pedagogy; he is at his best when he favors the former.

In view of the garrulousness and complexity of Sayles’s approach, it is no small thing to say that A Moment in the Sun is his most expansive and populous work yet. The Wilmington story alone provides plenty of material for a historical novel; in fact the few African-American writers bold enough to challenge Waddell’s official version of events published their accounts as fiction. Of the eight main characters in A Moment in the Sun, six of them belong to Wilmington families: the Manigaults, who are white gentry; the family of Dr. Lunceford, a black doctor prominent in Wilmington’s “sepia society” who is rich enough to keep his own servants; and the darker, poorer Scotts, who live across the tracks in Brooklyn. Sayles devotes nearly two hundred pages to Wilmington—a short novel, in other words—though this makes up only a fraction of the book’s length. A Moment in the Sun runs 955 pages, but that figure is deceptive. The designer has narrowed margins and reduced font size; with a little breathing room the page count might easily drift beyond 1,500. The novel is an encyclopedic portrait of an American era when imperial, racist, and plutocratic power were asserted with exceptional force.

Advertisement

Besides the novel about Wilmington, Sayles also intersperses two separate war novels: the first follows a regiment of black soldiers during the Spanish-American War; the second embeds the reader on both sides of the Philippine-American War (also the subject of Sayles’s new film, Amigo). There is a novella about the Klondike Gold Rush, and what amount to stand-alone short stories about the assassination of President McKinley at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, a tense baseball game between black and white soldiers in a Chattanooga army camp, the travails of a sickly Lower East Side newsboy, and a Chinese peasant girl’s flight from a rural village in Shandong province to a Hong Kong whorehouse.

Most of these stories involve some combination of Manigaults, Luncefords, and Scotts, a Filipino insurgent named Diosdado Concepción, and Hod Brackenridge, an itinerant laborer who has worked “every donkey job” known to man. But there are hundreds of other characters as well, of whom several of the least significant are granted their own chapters, along with interludes of newspaper headlines, descriptions of political cartoons, popular songs, a film synopsis, and gun advertisements.

The effect can be both exhilarating and chaotic. The chapters on the siege of El Caney in Cuba and the Battle of Manila Bay reminded me of what it felt like to study for a history exam: you proceed tentatively, painstakingly, cursing your teachers for not preparing you better. Unless you wrote your college thesis on the Philippine theater of the Spanish-American War, you will spend many pages in confusion. When exactly was “the time of the Katipunero uprising?” Who were the Bonifacios and why were they “led away to be slaughtered”? The accumulation of place names, many of them mentioned in passing, overwhelms. It is not fun to put down the book in order to Google “Bacoor,” or “Binondo,” or “Biak-na-Bato.” But it’s even less fun to be lost in the middle of the Filipino jungle without a map or compass.

Once you find your way around Wilmington and Manila and Skaguay, Alaska, it is much easier to lose yourself in the stories. Much of the book’s energy derives from large, boisterous scenes—parades, political speeches, theatrical performances, boxing matches, public executions, riots, and, of course, battles. But Sayles also understands that in novels, unlike in history books, personal crises weigh far more heavily than any war or revolution. So while the siege of El Caney is vivid and tense, it is not nearly as powerful as Royal Scott’s withdrawal from the Cuban battlefield with an old friend, Little Earl, who has been shot in the neck. Royal must get Earl to the field hospital, all the time reassuring him that the wound is not fatal, even though both men know that it is. The Klondike episodes are enthralling because Sayles wisely ignores the gold rush itself, focusing on a series of confidence games that ensnare Hod Brackenridge, who never even makes it to the gold fields. The drama is in the tension between Hod’s honorable instincts and the cynical schemes he must master in order to survive.

And as terrifying as the Wilmington massacre is, Dr. Lunceford finds himself in a more daunting situation later in the novel, after his property and possessions have been confiscated and he is forced to flee with his family to New York City. Lunceford’s teenage daughter, Jessie, is pregnant out of wedlock with Royal Scott’s child—for Lunceford, a source of deep shame. But in their squalid Hell’s Kitchen apartment, when Jessie’s water breaks prematurely, Lunceford is in the awkward position of having to deliver his own grandchild. He knows it will be a difficult birth, that the baby “will be undersized, discolored, the digestive tract not finished, the lungs prone to atelectasis, susceptible to infection….” Worse, he has no proper obstetric equipment, only a scalpel, a needle, and “an ancient Sims speculum in his bag that at the moment seems a device of torture rather than diagnostics.” The greatest obstacle, however, is his own rage. “This is the consequence…of her own actions,” he thinks, before injecting his daughter with a cocaine solution. A Moment in the Sun is filled with scenes like these, in which impoverished characters struggle to deal with desperate situations. They may lose their lives, but they never lose their dignity.

Advertisement

One question persistently recurs: Why 1898? What is it about the turn of the last century that has gotten Sayles’s attention? Certain clues appear often enough to suggest a motive, most obviously in the sections relating to the Spanish-American War. Seconds before William McKinley is shot by his assassin, Sayles has the President say, “We could not abandon the Philippines to paganism and anarchy,” a fictional anecdote that recalls George W. Bush’s “The United States will not abandon Iraq. We will not leave that country to the terrorists,” as well as John Boehner’s avowal not to “abandon Iraq and leave the country in chaos.” There is a heavy tint of dramatic irony when Junior Lunceford writes to his father from the battlefield in the Philippines that “the men don’t speak of the whys and wherefores of our presence here, but…we must, as always, trust our leaders….” Elsewhere Junior is less trusting: “We have been abandoned here to die by an unprepared and uncaring government. There is…seemingly no plan for what follows the ‘liberation’ of this island and these people.” In those quotation marks around “liberation” you can catch a wink from the twenty-first century.

As the Spanish-American War morphs into the stalemated Philippine-American War, the nature of the fighting changes. The ragged Philippine insurgents, aware that they cannot defeat the American occupiers in a traditional battle, resort to guerrilla warfare and attrition. “If we can keep them sick and sleepless and longing to go home, then victory may be within our grasp,” says a spokesman for a Filipino general. Another freedom fighter remarks that “the yanquis are impatient people, and if they think this war is a disease they can never shake, persistant and painful, maybe they will go home.”

Near the end of the novel, Sayles writes: “It has become that kind of fight, like a handful of wasps worrying a water buffalo. No way they can bring you down, but now and then you get stung.” And if none of this was clear enough, Sayles summons Mark Twain himself. “I am an anti-Imperialist,” Twain tells a reporter. “Our situation in those islands…is an utter mess, a quagmire, from which each fresh step renders the difficulty of extraction immensely greater.”

There are other gestures toward recent history. The violence in Wilmington, for instance, is set off in part by fear that a black man might assume high government office. In one of the novel’s more disturbing scenes—made more so by the fact that Sayles is quoting verbatim from an actual speech—South Carolina senator “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman tells a crowd at a political rally, “We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern white men and we never will!” And Sayles evokes some of today’s rhetoric when he has Tillman castigate Washington politicians as tools of “Wall Street” who have doomed the humble workers of America’s heartland to economic servitude. “Your politicians have betrayed you,” he declares, to rousing cheers. There are further glimmers of current issues, particularly of the abuses endured by undocumented day laborers—only here the workers who wait on street corners to be picked up by men in trucks are not Mexican illegals but women.

Yet Sayles reserves the greatest part of his energy for his almost fanatical reconstruction of a period that has vanished from public memory. The depth of his knowledge is at times uncanny. We learn, for instance, that the clap was treated by injecting a solution containing fine silver dust directly into the urethra, and that what is now Floyd Bennett Field was once an island where dead horses were rendered. And we learn too much about nineteenth-century obstetrical tools: the cephalotribe, the trephine perforator, the blunthook.

More than anything, Sayles is interested in work. It is difficult to think of a living writer who has taken such delight in the chronicling of skilled labor. Some examples come to mind—the glove manufacturers in Philip Roth’s American Pastoral, for instance, or the tunnel diggers in Colum McCann’s This Side of Brightness (also set at the turn of the century). But more apposite are the naturalistic novels of writers such as Émile Zola, Frank Norris, and William Dean Howells, with their miners and farmers and print-setters and butchers.

Sayles, for his part, teaches his readers how to distill turpentine from pine trees, slaughter a hog, and clean ears professionally (“the cleaner goes in with a set of pinchers…”). We also learn the finer tricks of cooperage (you need to gouge the croze so the head fits in tight); poppy farming (“choose only the pods that are standing at attention”); and linotype operation (make sure that the timing pin meshes into the clutch), among countless other trades.

Such passages, though often irrelevant to the story, are written with such exuberance that the effect can be hypnotizing. This, for example, is how you dispose of a dead horse:

If the shoes have been left on they get pulled off and tossed into the pile and sold back to the ferriers. Jubal yanks the hooks into the tendons just below the hocks on a big roan’s back legs so it can be winched down the slide, then pops the shoes off as fast as he can. It goes a lot faster when they’re dead.

The scrapers are next, running their quick blades over the body, razoring off manes and tails, separating the hair by color if it’s for brushes or not if it’s for plaster, and then the skinners step in slicing and tugging, tossing the heavy wet hides into a heap for the tanner’s boy to haul off in his wheelbarrow, a cloud of flies bursting apart with each new toss and then settling back on top. A man comes in to fog the whole floor three times a day but the flies always come back. The blood-smeared butchers come last, one on each side of the chute, hacking out the cuts they want and dropping them into steel carts, stripping one side of the skinned animal then digging in their meat-hooks to flip it over and do the other. What is left gets hauled up the ramp, unhooked, and slid into the enormous rendering vat.

There are times, however, when Sayles’s cataloging becomes excessive. The Philippines, again, are especially treacherous territory, as an attempt at verisimilitude drives Sayles to translate every third word into Tagalog or Spanish. In one typical paragraph Diosdado crosses fields of “petsay” bean fields before reaching a “vast huerta” of old mango trees, “abuelos,” that are “laden with hundreds of carabaos.” This mania for italicization is especially maddening when he applies it to words, like Madeira and aficionado, that are identical in English.

Sayles can lose control, but over its 955 pages A Moment in the Sun is almost never dull. Though he is fascinated by the era, he doesn’t idealize it, as the excruciating accounts of nineteenth-century medical practices make clear. Ultimately, the nostalgia is not for a lost time, but for a type of novel that one rarely encounters anymore. In his historical epic—a forgotten genre itself—Sayles relies on a member of neglected conventions: a roving, omniscient narrator; an unambiguous political partisanship; a Manichaean approach to characters in which the heroes struggle to earn their daily bread and the villains preach white supremacy; and capacious, messy, impassioned storytelling. In the right hands, these strategies still retain the ability to excite and transport. A Moment in the Sun is evidence, and a reminder that this form of fiction needn’t be relegated to the rendering vat.

This Issue

August 18, 2011

What Were They Thinking?

Fooled by Science

How Google Dominates Us