Isaac Casaubon (1559–1614) was a stern, driven, French-Swiss classicist who may be best known now for having lent his name to the dismal Edward Casaubon of George Eliot’s Middlemarch. Eliot cast her Mr. Casaubon as an obsessive drone who spends his days slogging away at a Key to All Mythologies—as if so pure a pedant could ever have picked his way through that gossamer realm of story and song. Formidably learned herself, she must have relished the differences between her fictitious Edward—by now a mythic figure in his own right—and the eminently real Isaac.

Yet Isaac Casaubon shared one crucial quality with his invented relative: he devoted inordinate portions of his life to rummaging through the cluttered attics of human learning. As a good Calvinist, however, the real Casaubon turned all those rummagings into a distinguished series of published books, including one with almost the same cosmic scope as Eliot’s imagined Key to All Mythologies. Isaac Casaubon’s On Matters Sacred and Ecclesiastical (De rebus sacris et ecclesiasticis) was first published in 1614, the year in which its industrious author died at the age of fifty-five, slain by a terrible infection of the urinary tract brought on, at least according to his physician, by years of refusal to rise from his reading desk to answer the calls of nature.

To On Matters Sacred and Ecclesiastical, as to several other works of similar or still greater bulk, Casaubon brought a finely tuned mind, a masterful command of Greek and Latin, and all the religious baggage with which his time—the Reformation—and place—the religious battlegrounds of Northern Europe—could load him. That combination of quick wit, intense religious faith, and phenomenal industry eventually took him into an entirely new world of learning. “I Have Always Loved the Holy Tongue” explores this famous classicist’s encounters with another ancient language, Hebrew, and, through Hebrew, with the whole weight of Jewish tradition.

Casaubon did not come by any of his learning easily. Turmoil surrounded him from the moment of his birth, for he came into the world a Huguenot, a French Calvinist, thirteen years before the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572, when Catholic troops would slaughter his coreligionists in every corner of France. Anthony Grafton and Joanna Weinberg introduce us to this strong, determined scholar by considering a particularly illuminating and unusual aspect of his scholarly life: his efforts to study Hebrew in depth. To do so, in Casaubon’s circumstances, was not a simple task. If Christians were at one another’s throats during the Reformation, the prospects were still more dire for Jews.

But Casaubon’s own story is quite a tale in itself: his birth in Geneva to exiled parents, their return to France despite the growing threat of civil war, the Catholic patrols that continually threatened their safety (Isaac first learned Greek while hiding out in a cave!), and the endless troubles he faced seeking employment in the middle of religious war. Like his parents, he eventually moved to Geneva, where he studied and then taught Greek at the Academy founded by John Calvin (and where he overlapped, briefly, with the heretic philosopher Giordano Bruno). Much of this Grafton and Weinberg describe in their book, although not as part of a continuous account of his life. Though they do make some acute observations about Mark Pattison’s Victorian biography of this remarkable scholar, a concise introductory précis of Casaubon’s career would probably have been useful to many readers.

Despite the stifling hierarchies of the Calvinist Academy (memorably lampooned by Bruno), Isaac carved out an active life for himself, including a growing family; the real Mr. Casaubon would eventually father seventeen children. In 1596, he moved back to France, to the University of Montpellier, and then, in 1600, to Paris, first on a royal pension from Henri IV and then, in 1604, as royal librarian. Henri’s assassination in 1610 made conditions increasingly difficult for a Protestant, and in this same year Casaubon moved to England, supported by a pension from King James I; by this time his contemporaries counted him as one of the most learned men in Europe, second only, perhaps, to the redoubtable Joseph Scaliger at Leiden.

In complex ways, Casaubon’s extreme circumstances determined the choices he made as a man and as a scholar: resolving to study the ancient Greeks and Romans as battles raged around him, concentrating his efforts on a few particular ancient Greeks among a legion of other possibilities. The authors who captured his attention were not the figures who dominate classical scholarship today, although Casaubon certainly knew the epic writers like Homer and Vergil, the dramatic poets of Greece and Rome, and the historians of fifth-century Athens and the early Empire, all of them reliable providers of solace in dangerous times (the current Oxford edition of Thucydides still cites Casaubon as an authority on the ancient text).

Advertisement

By and large, however, he nourished other tastes, devoting his hours to authors from the later, more cosmopolitan phases of Greek and Roman history, plunging into the work of writers who preferred to register witty conversations rather than majestic principle or bitter outrage: sardonic Theophrastus, for example, a student of Aristotle who left a series of merciless character sketches (the Characters), and chatty Athenaeus, whose long dialogue The Sophists at Dinner (Deipnosophistae) presents philosophy as anecdote, as sophisticated table talk rather than Plato’s call to urgent, life-altering action. What made a sixteenth-century Huguenot seek out this debonair company, in his life of danger and adversity, rather than Sophocles?

Why, indeed, did Casaubon study the classics at all? In significant measure, the Reformation reflects what happened when fifteenth- and sixteenth-century scholars transferred their careful, critical reading of ancient Greek and Latin texts to their reading of the Bible: Why, the Reformers demanded, did the institutional Church declare that there were seven sacraments when the Gospels only describe two, baptism and communion? How could Rome defend practices and institutions, including the papacy, that had no warrant in the Bible?

Grafton and Weinberg clearly show that, in some significant way, Casaubon’s aggressive efforts to clarify classical texts, to free them from the errors accumulated in centuries of transcription, are intimately connected with the practice of his Protestant faith. His laborious efforts to correct the grammar and spelling of ancient manuscripts, his reams of explanatory comments, are more than just an attempt to save order from the chaos of disintegrating religious and political certainty, more than a struggle to find a secure place untouched by civil war; they are, in themselves, a spiritual exercise. They are also, of course, an effort to communicate as sincerely as possible with people divided from him by time, culture, language, and mortality, from the ancients of the Mediterranean to the Jews he met in his own life.

Indeed, the prime mover of Casaubon’s Hebrew studies must have been his desire to read the Bible as he had always read the classical authors: in the original language, from beginning to end, from the Iron Age Hebrew of the Pentateuch to the intercultural koinê (“common”) Greek of the New Testament, fitting words and script together until he could hear a clear voice ringing forth—in the case of ancient languages, ringing forth from beyond the grave—rediscovering, or recovering, a young person’s capacity for pure wonder. This is what Isaac Casaubon did throughout his life, moving from Latin to Greek, Greek to Hebrew, Hebrew to Aramaic, from the classics to the Talmud. His studies of texts were also, to a great extent, studies of people.

He was still learning, still eager to learn, up to the end, wrestling at a relatively advanced age with dense rabbinical texts in an era newly saturated with printed books. It has been a long time since any one person could claim to know practically everything, either in our day, in Casaubon’s sixteenth century, or in the period that fascinated him most of all: the age of Alexandria, of the growing Roman Empire, the period when a series of events in the Roman province of Judaea brought about the birth of his cherished Christianity. But his passion to know continued to drive him beyond the limits of his body and brain and the imperfections of the world around him.

Casaubon knew enough to appreciate the tangle of roots from which Christianity arose as a new religion. A fourth-century mosaic in the Roman church of Santa Sabina proclaims, proudly and truly, that the Christian church had two mothers, what the mosaic’s inscriptions call “the church of the Jews” and “the church of the Gentiles.” Both mothers are stately matrons, modestly veiled, each bearing a book, but they are differently dressed, with different texts in hand, in different scripts, and they each represent a tradition so dense that a single person might command one part of their heritage—written, cultural, ritual—but never, apparently, both.

As a result, every aspect of early Christianity, but also of Roman-period Judaism—and, for that matter, the ancient religions of Greece, Etruria, and Rome—was always a matter of ceaseless translation and negotiation. Everyone, without exception, saw the great cultural syntheses of the ancient Mediterranean through a glass darkly. To take just one example, Saint Augustine, surely one of the mightiest intellects ever to walk this earth, applied Plato’s teachings to Christian theology without ever mastering Greek, let alone Hebrew; with his tremendous gifts and his tremendous privations, he simply did the best he could under his circumstances.

Advertisement

As we read in Grafton and Weinberg’s book, it was this transitional period of late antiquity and early Christianity, so mysterious and so eventful, that became Isaac Casaubon’s particular obsession in the waning years of the sixteenth century, when his curiosity drove him to learn the “Holy Tongue” and then push beyond it. Like most European Christians then and now, he had come to his faith through translations of the Bible: for Protestants like himself, this meant first a vernacular translation, then, as his education proceeded, the Latin of Saint Jerome’s Vulgate. Learning Greek allowed him at last to read the Gospels and the rest of the New Testament more or less as they had been written. He could also read the ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, the Septuagint, drafted in Hellenistic Alexandria (begun in the third century BCE, finished before 132 BCE) by a team of some seventy scholars (septuaginta is Latin for seventy) to serve the Greek-speaking Jews of that cosmopolitan city (many of them as shaky in their Hebrew as their modern counterparts).

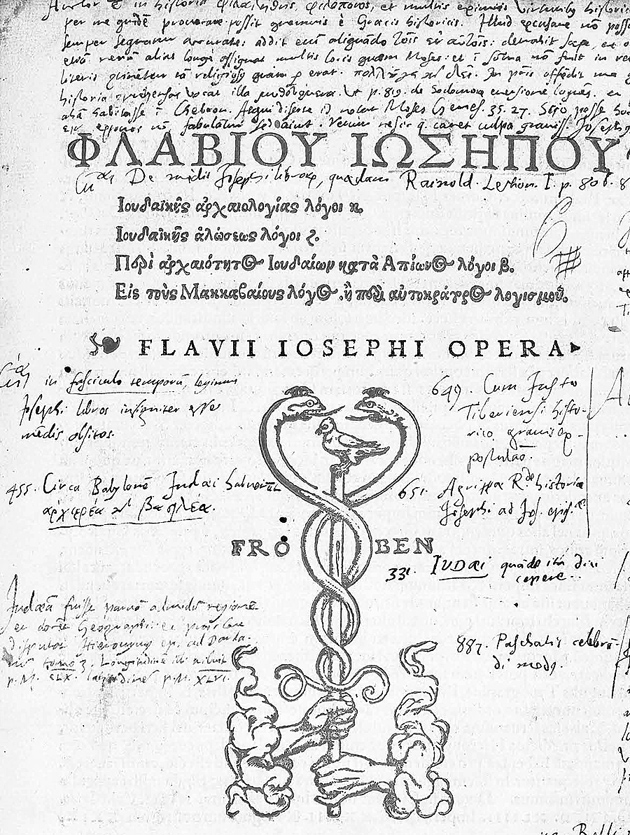

Casaubon, like many Protestant scholars, had made a study of Hebrew in his youth, but in his early thirties, as a more established professional, he began to pursue the language in earnest, driven by his inexhaustible curiosity and what must have been a considerable physical vigor. As he gained confidence in Hebrew, that curiosity took him still further: into Aramaic, the colloquial language of Judea that was spoken in early Christian times, into the more contemporary Aramaic of the Talmud, the body of commentaries preserved and expanded by rabbis through the ages, and at last into contemporary Yiddish. Grafton and Weinberg trace the state of Casaubon’s studies step by step by examining the copious notes he wrote—in indelible ink—in the margins of the books he owned.

Librarians today blanch at the thought, but from ancient times onward, writing in margins was a time-honored proof of active readership. People jotted down illustrations, comments, alternatives for words that puzzled them (manuscript copies were usually riddled with imperfections), significant passages from other writers, and an inexhaustible collection of strange facts and strongly held opinions. (For example: one marginalium to Homer’s Iliad goes on at great length about earthworms, comparing their emergence from the soil to the human soul’s emergence into the divine light; a manuscript of Vitruvius in the Bodleian Library in Oxford finishes off the Ten Books on Architecture with a recipe for curing hemorrhoids with white bean paste and oil of violet; a fifteenth-century copy of Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy has a self-portrait of the manuscript’s red-haired owner, moping melancholically as he says, “Console me, Mother Philosophy—an evil woman has done me wrong,” and Mother Philosophy obligingly tells him just where to look in the text of Boethius to pilot the ship of his soul into the port of salvation.)

The people who copied these eagerly annotated manuscripts often copied the marginalia as well as the main text, so that many medieval and early modern manuscripts present tiny blocks of some treasured original floating in a sea of commentary; early printed volumes, especially on the classics, law, or religion, often imitated the same format. By manhandling the books he owned and read, Casaubon was only doing what everyone around him did—and besides, paper in his day was expensive (not least because it was of such excellent quality). Although Casaubon also kept notes in an erasable donkey-skin notebook, he habitually jotted down his reactions to his reading, and his future plans for writing, right in the books that inspired him, or irritated him into action.

These marginalia allow Grafton and Weinberg to trace the development of Casaubon’s linguistic proficiency in Hebrew and Aramaic, and of the thoughts sparked by his new expertise. Most of “I Have Always Loved the Holy Tongue” consists in a painstaking comparison of Casaubon’s thick marginalia with the ideas that eventually appear in his published work. Although they twice describe his handwriting as “chicken scratches,” that description applies to his informal notes (which he himself found illegible on occasion); most of the time, in his defense, Casaubon writes a clear, legible script in Greek, Latin, and Hebrew square lettering, so clear, in fact, that it is readily decipherable in the book’s generous collection of photographs.

There was a definite feeling among literate people in the early modern world that clear texts and clear handwriting were essential to developing a clear mind (although the supremely lucid Thomas Aquinas had truly awful penmanship; spiky and spidery, it really does suggest chicken scratches). Isaac Casaubon’s script normally complements his drive to clarify, and if need be, to correct the spelling and grammar of ancient classical works in order to clarify his thoughts about matters ancient, modern, and eternal.

As the mature scholar’s knowledge of Hebrew and Judaic tradition grew, his thoughts became increasingly preoccupied with the Jewish contribution to Christian religion, from the time of Jesus, through Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, right up to his own era. Characteristically for this cosmopolitan man, his growing enthusiasm encompassed not only a written tradition of texts and languages, but also the living people who had produced and preserved that tradition in the first place: the Jews.

If Huguenots were persecuted in sixteenth-century France, the fate of European Jews had been troubled for a very long time. The story of Isaac Casaubon’s Hebrew and Jewish studies, therefore, is also, significantly, the story of Jewish–Christian relations in early modern Europe, a story that is still imperfectly known, and often difficult to trace. Much of the evidence for contact between Christians and Jews is anecdotal, and these isolated anecdotes may, in fact, reflect the way that the two religious creeds interacted most of the time: individually, episodically, and not always in line with the commands of prevailing law, custom, or prejudice.

Jewish communities had survived in Rome and southern Italy ever since ancient Roman times, some with strict observance of kosher rules, others assimilated to varying degrees, still others recent converts. Since then, however, a long, terrible history of persecution has disrupted Jewish communities in Europe for centuries, destroying people, possessions, and documents. Nor is it easy to find people who can read and interpret what evidence is left: that evidence survives in old writing, in old artifacts, in multiple languages. Furthermore, what people declare in surviving records has often been deliberately misleading: sixteenth-century Spanish officials in Naples and Sicily routinely reported back to Madrid that they had expelled all the Jews from their territory. Yet Jews still show up in their records. Some had been summarily baptized and therefore counted as “New Christians”; some continued to live more or less as they always had. During Casaubon’s lifetime, in commercial emporia like Hamburg, Antwerp, or the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, virtually every aspect of Jewish life could be negotiated and renegotiated: mercantile practice, clothing, residence in the Ghetto, keeping kosher, dealings with Gentiles.*

In the beginning, typically, Casaubon learned Hebrew from a Christian scholar, in his case at the Geneva Academy, in his twenties, from Pierre Chevalier. But he was too much of a classicist ever to have been satisfied with the bare biblical text. He wanted to know the comments and interpretations that other readers had added down the centuries—in its own way, his life of study, like his life away from his desk, was eminently, intensely social. Most commentators on the Hebrew Bible had been Jews, writing, for the most part, not in Hebrew but in Aramaic. So Casaubon set himself to learning Aramaic and, eventually, Yiddish—whatever it took to understand and to communicate. Grafton and Weinberg trace his growing competence as his readings broaden out to take in new eras, people, places, languages, and cultures. His exploration of the “Holy Tongue” was a lifelong enterprise, pursued in a spirit of rare humanity.

This humanity showed forth above all in his behavior to one individual living Jew who had helped him in his studies. Casaubon met Jacob Barnet on a visit to Oxford in 1613, and was struck immediately by the younger man’s expertise on the Talmud, the great body of Jewish commentary on every kind of religious question. It was the first time that this eager scholar of the Holy Tongue had ever met a living, practicing Jew. England had expelled its Jewish population in the fourteenth century, and Barnet was a rarity. He had come from Italy, his presence at Oxford eased by his stated intention to convert to Christianity. He and Casaubon sat down to long talks about life, scholarship, and Talmud; the older man’s marginalia in his books indicate how excited he was by having, at last, a living guide to this ancient Jewish tradition. As time went on, however, Barnet’s position became more difficult; he left Oxford, and returned. Now his Oxford colleagues, the King, and the Archbishop of Canterbury pressed him more and more insistently to convert in a grand public ceremony. At last the pressure overwhelmed him. On the scheduled day, he ran away. Chased down on horseback and apprehended, Barnet was cast into the university jail, confined with particular brutality because of the blasphemies he uttered at the time of his arrest.

Like a seventeenth-century Amnesty International—and unlike his scholarly colleagues—Casaubon lobbied tirelessly on the young man’s behalf, pressing the authorities at Oxford:

Please, don’t pass too severe a sentence on him. Let the obstinate Jew recognize the kindness of Christ in the clemency of those who profess Christ’s name…. Allow me to put off all shame before you on behalf of that man, whom it was my lot to have as a teacher.

Remarkably, Casaubon’s campaign succeeded: Jacob Barnet left prison, retreated to the Continent, and, after reaching Paris, melted, so far as we know, into oblivion, like so many refugees in those dangerous times.

It is precisely Casaubon’s willingness to defend, in public, a friend—a persecuted, ostracized friend—that elevates the record of his achievements from a simple history of scholarship to a life. In their account of Casaubon’s Hebrew studies, Grafton and Weinberg have illuminated far more than the scholar; they have done much to reveal the multiple sides of a deeply sympathetic figure who must have been, in many respects, a thoroughly modern man.

-

*

A wealth of new evidence is collected in Edward Goldberg, Jews and Magic in Medicean Florence: The Life of Benedetto Blanis (University of Toronto Press, 2011). ↩