William Stuntz was the popular and well-respected Henry J. Friendly Professor of Law at Harvard University. He finished his manuscript of The Collapse of American Criminal Justice shortly before his untimely death earlier this year. The book is eminently readable and merits careful attention because it accurately describes the twin problems that pervade American criminal justice today—its overall severity and its disparate treatment of African-Americans.

The book contains a wealth of overlooked or forgotten historical data, perceptive commentary on the changes in our administration of criminal justice over the years, and suggestions for improvement. While virtually everything that Professor Stuntz has written is thought-provoking and constructive, I would not characterize the defects in American criminal justice that he describes as a “collapse,” and I found his chapter about “Earl Warren’s Errors” surprisingly unpersuasive.

Rather than focus on particular criminal laws, the book emphasizes the importance of the parts that different decision-makers play in the administration of criminal justice. Stuntz laments the fact that criminal statutes have limited the discretionary power of judges and juries to reach just decisions in individual cases, while the proliferation and breadth of criminal statutes have given prosecutors and the police so much enforcement discretion that they effectively define the law on the street.

Ironically, during an age of increasing protection for civil rights, discrimination against both black suspects and black victims of crime steadily increased. Stuntz attributes this development, in part, to the expansion of prosecutorial and police discretion—in his view, “discretion and discrimination travel together.” For example, the discretionary authority to enforce posted speed limits has enabled state troopers to be selectively severe in making arrests, and to use those arrests to justify searches for evidence of drug offenses. While Stuntz does not suggest that such discriminatory enforcement of traffic laws is itself a national crisis, it provides one illustration of the negative effects of excessive enforcement discretion.

The result, Stuntz writes, has been a serious disadvantage to African-Americans in their encounters with the American criminal justice system. While only 10 percent of the adult black population uses illegal drugs, as does a roughly equal percentage—9 percent—of the adult white population, blacks are nine times more likely than whites to serve prison sentences for drug crimes. “And the same system that discriminates against black drug defendants also discriminates against black victims of criminal violence.” As “suburban voters, for whom crime is usually a minor issue,” have come to “exercise more power over urban criminal justice than in the past,” police protection against violent felonies has disproportionately extended to suburban neighborhoods rather than the urban centers where more black individuals reside.

The “bottom line,” Stuntz explains, has been that “poor black neighborhoods see too little of the kinds of policing and criminal punishment that do the most good, and too much of the kinds that do the most harm.” In this sense and others, Stuntz concludes, our criminal justice system has “run off the rails.”

A major part of the book includes a historical narrative that identifies the sources of this discrimination against African-Americans and also explains the severity of our treatment of all offenders. The severity of the system is almost as disturbing as its discriminatory impact. In the years between 1972 and 2007, the nation’s imprisonment rate more than quintupled—increasing from 93 to 491 per 100,000 people. The rate at the end of that period vastly exceeded the analogous rate in other Western countries, which varied from 132 for England and Wales to a mere 74 in Germany and 72 in France. Moreover, during those years,

The number of prisoner-years per murder multiplied nine times. Prisons that had housed fewer than 200,000 inmates in Richard Nixon’s first years in the White House held more than 1.5 million as Barack Obama’s administration began. Local jails contain another 800,000.

Rather than a “collapse,” however, these figures suggest to me that the current system of criminal law and enforcement (like too many of our citizens) has grown obese.

Stuntz believes that two enormous migrations that led to crime waves largely define the history of crime and punishment in the United States. The first occurred during the seventy years preceding World War I when over 30 million Europeans came to America and settled primarily in cities in the industrial Northeast. The second occurred during the first two thirds of the twentieth century when seven million blacks left the rural South and moved into the same cities. To put simply Stuntz’s description of the central difference between those two migrations: during the European migration, urban politics soon produced local police forces made up of officers who were similar to and resided among the residents of the areas they were protecting—Irish-Americans trusted Irish cops from the neighborhood to treat them fairly—whereas during the black migration, the white majorities living in suburban areas selected the prosecutors and police officers who enforced the law in black urban neighborhoods.

Advertisement

During the Gilded Age, crime was not controlled chiefly through punishment, but rather through local democracy and the network of relationships that supported it:

Police officers sometimes lived in the neighborhoods they patrolled, and had political ties to those neighborhoods through the ward bosses who represented their cities’ political machines. Those patrols happened on foot: officers, those whom they targeted, and those whom they served knew one another. Cops, crime victims, criminals, and the jurors who judged them—these were not wholly distinct communities; they overlapped, and the overlaps could be large.

Stuntz is careful not to romanticize that justice system because he recognizes that while policing was then “more relational,” it was also “more brutal, more corrupt, and lazier,” as police officers licensed vice and merely regulated crime, rather than enforcing prohibition of it.

It is fair to infer, however, that the relationships between the police and the residents of high-crime neighborhoods have a significant impact on the amount of crime that prevails in those areas. The dramatic difference in the homicide rate in the area where I grew up and President Obama lived before moving to Washington—“Chicago’s upscale, racially integrated but mostly white Hyde Park”—and the “neighboring Washington Park, with a poor, 98 percent black population,” certainly suggests that there is a material difference in the quality of the police protection available in those neighboring areas. In Hyde Park, the homicide rate is 3 per 100,000; in Washington Park, it is 78 per 100,000.

One suggestion implicit in much of the book is that a more prompt and vigorous attempt to take affirmative steps to enlist black police officers to protect black neighborhoods with which they are locally connected might well have been wise. I am reminded of the powerful argument set forth in an amicus curiae brief filed eight or nine years ago in Grutter v. Bollinger, the University of Michigan affirmative action case.

The brief was filed by twenty-nine military leaders, including men like General Wesley Clark and General Norman Schwarzkopf and several others who had achieved four-star rank. Those amici were thoroughly familiar with the dramatic differences between the pre-1948 segregated armed forces and the modern integrated military, and their brief recounted the transition from the former to the latter. Within a few years after President Truman’s 1948 Executive Order abolishing segregation in the armed forces, the enlisted ranks were fully integrated. Yet during the 1960s and 1970s, those ranks were commanded by an overwhelmingly white officer corps.

The chasm between the racial composition of the officer corps and the enlisted ranks undermined military effectiveness in a number of ways set forth in the brief. Among these was the failure of enlisted service members to report maltreatment to their commanding officers. In time, the leaders of the military recognized the critical link between minority officers and military readiness, eventually concluding that “success with the challenge of diversity is critical to national security.” They met that challenge by adopting race-conscious recruiting, preparatory, and admissions policies at the service academies and in ROTC programs.

The historical discussion in that brief did not merely imply that a ruling outlawing comparable programs would jeopardize national security; it also implied that an approval of Michigan’s admission policies would provide significant educational benefits for civilian leaders. The reasons for taking positive steps to create a diverse officer corps in the military surely apply as well to the need for staffing urban police forces with officers who are capable of relating to the communities they are responsible for protecting. Officers who inspire the trust of members of those communities may more effectively encourage crime-reporting and other forms of cooperation by them.

Stuntz believed that our Constitution overprotects procedural rights and underprotects substantive rights. He begins his discussion on this point by criticizing James Madison’s emphasis on procedure in our Bill of Rights, which he compares unfavorably with the relatively contemporary provisions of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man. Stuntz speculates that Thomas Jefferson, through conversations with the Marquis de Lafayette of the French National Assembly, may have influenced the drafting of the French Declaration. Notwithstanding those similar origins, Stuntz notes that the French document, unlike the American Bill of Rights, contained a definition of “liberty”—“the power to do anything that does not injure others”—and a substantive limitation on the power to criminalize conduct—“only such actions as are injurious to society.” While he recognizes that those French principles did not survive Napoleon’s rule, he implies that comparable provisions in our Bill of Rights might have restricted the virtually unlimited power of legislatures in America “to criminalize whatever they wish.”

Stuntz contrasts the pen of the great James Madison with the second-rate politicians of later times, who adopted “slapdash” institutional arrangements that too easily bend to the shifting winds of local politics:

Advertisement

America’s justice system suffers from a mismatch of individual rights and criminal justice machinery, between legal ideals and political institutions. When politicians both define crimes and prosecute criminal cases, one might reasonably fear that those two sets of elected officials—state legislators and local district attorneys—will work together to achieve their common political goals. Legislators will define crimes too broadly and sentences too severely in order to make it easy for prosecutors to extract guilty pleas, which in turn permits prosecutors to punish criminal defendants on the cheap, and thereby spares legislators the need to spend more tax dollars on criminal law enforcement.

In Stuntz’s view, constitutional law could reduce the risk of this “political collusion” by limiting legislators’ power to criminalize and punish. Madison’s text, by focusing on procedural instead of substantive limits, ignores “the core problem” posed by the strange design of our justice system.

According to Stuntz, the basic explanation for the mismatch is that the present institutions of American criminal justice did not develop until well after the drafting of the Bill of Rights, hence that document did not provide limits tailored to those institutions. The changes that occurred in the North between the Founding and the 1850s began the expansion of the power of local and elected officials in criminal law enforcement that later facilitated the excessive discretion and political collusion that Stuntz criticizes. Private tort-like enforcement of criminal laws gave way to full-time elected criminal prosecutors; elected state judiciaries wielded greater power than their appointed predecessors; politicized legislative codes began to substitute for common law crimes; urban police forces were organized, the first having been established in New York City in 1845; and the power of juries to determine whether given conduct merits punishment was narrowed.

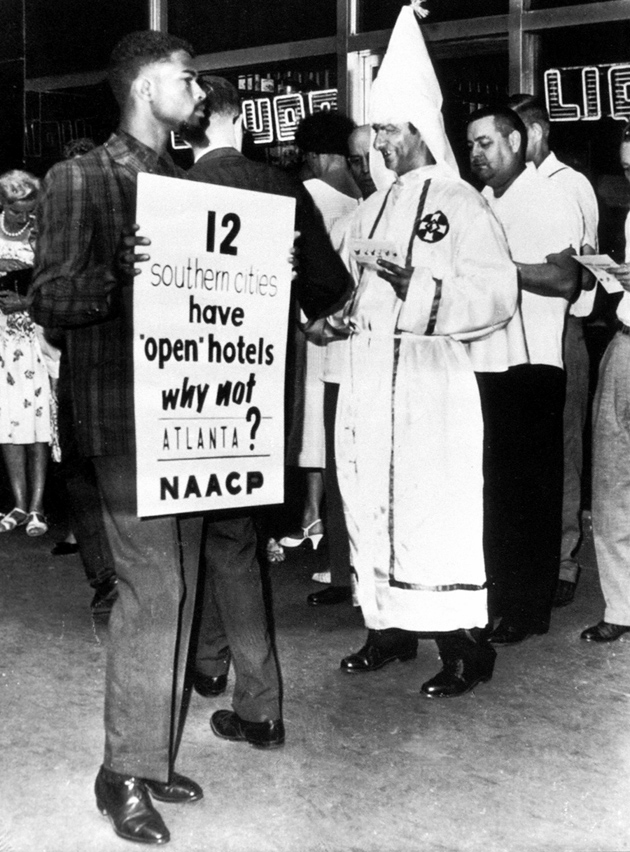

As a predicate for his analysis of the “failed promise” of the Fourteenth Amendment, Stuntz describes differences between the administration of justice in the northeastern states and the antebellum South, as well as two different kinds of violence against African-Americans during the early years of Reconstruction.

The three criminal enforcement systems in the antebellum South were the justice of courts, the justice that masters enforced over their slaves, and the justice of the mob. The second came to an end when the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery, and it seems clear that the Fourteenth Amendment was intended to end the all-too-common practice of lynching African-Americans and a surprisingly large number of their white sympathizers. Unfortunately, that practice survived the Civil War.

Stuntz provides us with brief descriptions of the two types of mob violence that illustrated the need for federal involvement in the protection of the new class of black citizens. In Memphis and New Orleans, white police officers played an active role in killing blacks, whereas in the tragic Colfax massacre on Easter Sunday in 1873, white Klansmen killed sixty-two black men—some of whom were unarmed and had attempted to surrender—without any active assistance from state officers. Broadly speaking, the Fourteenth Amendment might have been construed generously to authorize direct federal involvement in the prevention of mob violence in both types of cases, or more narrowly only to prevent state action, such as occurred in the Memphis and New Orleans mass murders.

In an Alabama case decided in 1871, then Circuit Judge William Woods interpreted the Equal Protection Clause to support the broader view: “Denying includes inaction as well as action, and denying the equal protection of the laws includes the omission to protect.” Judge Woods also reasoned that because “it would be unseemly for Congress to interfere directly with state enactments,” Congress’s power to enforce the amendment must have been intended to authorize legislation “which will operate directly on offenders and offenses.”

That broader view prevailed in a series of Klan cases, mostly in South Carolina and Alabama, which produced nearly six hundred convictions in federal courts in 1871 and 1872. It seems fairly clear that the large-scale enforcement effort by the Freedmen’s Bureau, federal prosecutors, and federal agents that produced those convictions was faithful to the intent of the Grant administration that had sponsored the Fourteenth Amendment and its implementing legislation.

The broad view, however, was rejected by the Supreme Court in the infamous case of US v. Cruikshank, decided in 1876, that arose out of the Colfax massacre. Stuntz argues that that decision is best understood as the product of political developments following the stock market collapse in 1873 that gave Democrats control of Congress. The opinion in Cruikshank emphasized the Fourteenth Amendment’s limits, concluding that it prohibited only state action and did not “add any thing to the rights which one citizen has under the Constitution against another.” Although I have reservations about accepting a political explanation for a judicial decision, there can be no doubt concerning Cruikshank’s unfortunate effects. The Court not only set aside the conviction of one of the Colfax massacre’s leaders, who had made a sport out of lining up black men at the parish to see how many he could execute with a single bullet, but its decision also judicially constrained the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection principle in a manner that has not been undone.

Stuntz’s description of the Colfax massacre and the Cruikshank decision draws heavily on Charles Lane’s exhaustive research in his recent book, The Day Freedom Died.* Stuntz convincingly explains why the rationale adopted by the Supreme Court was neither necessary nor faithful to the promise of the Fourteenth Amendment, and how it put an end to Klan prosecutions:

The change in the nation’s political tilt wrought by the depression of 1873 was temporary, as such changes always are. The legal change was permanent. The ideal of equal protection—the notion that all Americans are entitled not only to freedom from government oppression, but to a measure of freedom from private violence as well, and the same measure their well-to-do neighbors received—was, for all practical purposes, dead. So were thousands of southern blacks who needed that protection, and needed it badly.

Whether the Cruikshank decision was faithful to the intent of the men who drafted and ratified the Fourteenth Amendment rather than to the Democratic majority that had been elected in 1874 may well be debatable. I have no doubt, however, that the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which put an end to segregated public schools, represented an application of the equal protection guarantee that the original authors and ratifiers of the provision did not anticipate. Unlike Cruikshank, Brown gave effect to a broad vision of the equal protection guarantee, although not the particular broad view that Cruikshank had obliterated.

In the US v. Reese case, decided on the same day that the Supreme Court announced Cruikshank, the Court set aside convictions of Kentucky election officials for conspiracy to deprive a black prospective voter of his right to vote. They had refused to register him when he offered to pay his poll tax, but the Court held the statute unconstitutional because it did not require proof that their conduct was racially motivated. After that decision, in Stuntz’s view, “even Klan-influenced government officials were nearly unconvictable, thanks to the requirement that the omnipresent but unprovable discriminatory motive be established in every case.” Stuntz’s criticism of that decision for its overly stringent requirement of proof of motive may be correct, although elsewhere in the book he identifies the requirement for mens rea criminal intent as a valuable limitation upon law enforcement, and its absence in later statutes as a significant contributor to overenforcement of criminal law.

Stuntz identifies three Supreme Court decisions from the last three decades that he perceives to exemplify the impact of the errors that infected Cruikshank and Reese. I found that discussion especially interesting because although I had written a dissenting opinion in each of those three cases, I had not cited Cruikshank or Reese in any of those dissents. In McCleskey v. Kemp, in 1987, the Court rejected convincing evidence that in Georgia a black killer of a white victim more often receives the death penalty than when the victim is black or the killer is white, because the defendant had failed to prove a discriminatory motive by any relevant decision-maker in his own case. In US v. Armstrong, decided in 1996, the Court found insufficient justification for allowing discovery procedures in a trial judge’s firsthand knowledge about drug prosecutions, where such discovery almost certainly would have confirmed that the government tended to federally prosecute drug defendants who were black but to permit more lenient state court prosecution of those who were white. In Castle Rock v. Gonzales, decided in 2005, the Court found no constitutional violation where police failed to enforce a restraining order obtained by a mother against her estranged husband, who ultimately killed their three children.

McCleskey and Armstrong do indeed support the thesis that the Court has tolerated law enforcement practices that are discriminatory against African-Americans, but I do not re- member discrimination to be at issue in the outrageous failure of the police to do their duty in Castle Rock. Perhaps Stuntz means to suggest—consistent with his thesis earlier in the book—that the discretion afforded to law enforcers by Castle Rock, which found no constitutional entitlement to police protection, facilitates the unequal offering of police protection to crime victims of different races.

After the Court’s decision in Cruikshank, the federal government was not a major participant in law enforcement for decades. Stuntz describes the expansion of federal criminal law through the culture wars of the early twentieth century concerning lotteries, polygamy, prostitution, opium, and alcohol. In his discussion of harmful addictive substances, he does not mention tobacco but does contrast Prohibition with today’s continuing war on drugs.

Stuntz explains, “The chief drug war of the early twentieth century concerned alcohol, not any of the range of narcotics that so obsessed the late twentieth-century legal system.” Prohibition, authorized by the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act, is generally regarded as a “great disaster,” but was in fact more effective and a lesser cause of crime than often assumed. Among the benefits that Stuntz identifies were a decrease in alcohol consumption, caused in part by the significant increase in its price (a quart of gin, for example, rose from 95 cents to $5.90), and open discussion of the pros and cons of using alcohol.

While “the law of Prohibition may have been foolish,” it was also far less severe than the modern war against drugs. It did not prohibit the mere possession or consumption of alcoholic beverages, only their manufacture, sale, and transport; it exempted use in private homes and service to “bona fide guests”; and doctors were expressly permitted to prescribe the use of alcoholic drinks for therapeutic purposes. Today prison sentences are imposed for simple possession of marijuana and a long list of other controlled substances, and federal law (as upheld by the Court in a 2005 opinion that I wrote, Gonzales v. Raich) even bars possession of home-grown marijuana prescribed to combat the nausea that attends most cancer treatments.

Stuntz describes some harms of alcohol consumption and criticizes Prohibition, but he does not address facts about Prohibition’s enforcement costs or the consequences of its repeal. Those consequences obviously included the replacement of significant litigation and imprisonment costs with generous tax revenues, and expansion of profitable commerce in the production and marketing of alcoholic beverages. On the other hand, as Stuntz’s own reasoning suggests, those consequences also likely included an increase in alcohol consumption, which continues to have serious adverse social effects today.

Such a discussion of the pluses and minuses of the repeal of Prohibition might have provided information relevant to a debate on the wisdom of current drug enforcement policies. As Stuntz mentions, the absence of developed debate among present-day political leaders about drug policies is striking in light of the openness of the debate among political leaders in the 1920s and early 1930s—such as Al Smith, the Democratic presidential candidate in 1928—about the wisdom of prohibiting alcohol. In short, while Stuntz’s discussion of Prohibition is interesting and informative, it omits a potentially valuable assessment of how the lessons from Prohibition’s repeal might bear upon, and inform political debate about, the current war on drugs.

Extending his criticism of our system’s focus upon criminal procedure rather than substance, Stuntz’s eighth chapter concerns “Earl Warren’s Errors.” That chapter title is both misleading and inaccurate. It is misleading because much of the chapter does not describe “errors,” but rather unintended consequences of decisions—Mapp v. Ohio (1961) and Miranda v. Arizona (1966)—that I think were clearly correct.

Stuntz argues that because those decisions were unpopular, they undoubtedly provided ammunition to politicians who campaigned on promises to be “tough on crime” if elected, and that the success of their campaigns in turn led to the enactment of more and harsher criminal laws, such as the exceptionally severe drug laws sponsored by men like Nelson Rockefeller. It is quite unfair to criticize Earl Warren for his “poor timing” just because the Court found it necessary to make unpopular decisions when the public was especially concerned about rising crime rates. Indeed, a paramount obligation of the impartial judge is to put popularity entirely to one side when administering justice.

As a descriptive matter, Stuntz’s discussion of those unintended consequences does help to explain the severity of today’s criminal law. (Unfortunately, however, he omits analysis of the unintended consequences of the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984, which, in part by curbing judicial discretion, led to a dramatic increase in the severity of federal sentences, as well as the severity of those imposed by states that adopted comparable “reforms.”)

Stuntz minimizes the importance of decisions like Miranda and Mapp, which prohibit the use of probative evidence in certain cases, because the Supreme Court has developed waiver rules that enable the police to avoid their requirements. Moreover, he argues that reliance on such rules has produced a system in which defense counsel give primary attention to the litigation of procedural issues rather than to factual investigation that seeks to come to a correct conclusion on the issue of guilt or innocence. While there is some merit to such criticism, I think it abundantly clear that the rules do far more good than harm.

With particular attention to Miranda, as Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote in his opinion upholding Miranda against congressional abrogation a decade ago, the case “has become embedded in routine police practice to the point where the warnings have become part of our national culture.” Indeed, in my judgment, the decision played a major role in changing a police culture once riddled with incompetent, lazy, and brutal behavior into a law enforcement profession that is both more effective and also commands widespread public admiration for its dedicated public service.

Stuntz also comments in this chapter on the very live debate among the current members of the Supreme Court about the extent to which the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment—the right of the accused “to be confronted with the witnesses against him”—requires the exclusion of certain evidence obtained from witnesses who are unavailable at the time of trial. He is critical of two recent decisions that—like both Miranda and Mapp—require exclusion of probative evidence. I think Justice Anthony Kennedy, who dissented in both of those cases, might well have written the comments Stuntz offers. Stuntz argues that while “live witness testimony may have been the best possible means of proving guilt…when the confrontation clause was written and ratified,” “it hardly follows that it is the best possible means today” now that forensic and scientific analysis of physical evidence are more accurate. And he claims that “forcing crime laboratory technicians to double as courtroom witnesses raises the cost to the laboratories of performing the technical analysis,” which “mean[s] less analysis, and hence a less accurate adjudication system,” rather than one that reflects contemporary needs and capacities.

To the extent that Stuntz suggests that confrontation does not advance “any rational policy goal” because live witnesses are less important today than they once were, his argument is quite unpersuasive. Among other justifications, the Supreme Court majority in Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts (2009), explained that “confrontation is one means of assuring accurate forensic analysis.” Cross-examination permits a criminal defendant to probe the analyst’s competence, training, judgment, and incentives or pressure for manipulation of the results. Such questioning can expose flaws in the forensic testing process that undercut the reliability of such evidence, the very reliability about which Stuntz expresses concern.

The final chapter in the book is entitled “Fixing a Broken System.” It includes an appraisal of the likelihood of achieving various reforms, their potential costs and benefits, and the political problems they present. While some of Stuntz’s suggestions invite changes in judicial doctrine, his primary focus is on the need for important legislative change. He stresses four themes that have been identified in earlier chapters.

First, he persuasively argues that putting more police officers on city streets is a policy move that should reduce both crime and the number of prisoners. By deterring crime with broader, more certain enforcement rather than heavy punishments for the few most easily caught, this policy would respond both to the problem of excessive penal severity and to the twin effects of systemic racial discrimination—excessive enforcement against black offenders and inadequate protection of black victims.

Second, Stuntz believes that judicial interpretation of the equal protection guarantee in the Fourteenth Amendment should endorse the broad view that prevailed in the early years of Reconstruction, and that was rejected by the Supreme Court in 1876 in Cruikshank and more recently in McCleskey, Armstrong, and Castle Rock. His fundamental point is that the duty to govern impartially requires the state to provide all of its citizens with equal protection against violations of the law: no class should receive less police protection than another or be punished more severely for its crimes than another. The Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against disproportionate punishments also applies that equality principle. The Court’s recent decision prohibiting Florida from imposing a sentence of life without parole on a juvenile for a non-homicide offense is a step in the right direction because such a penalty is almost never imposed in other jurisdictions. Stuntz suggests other means of avoiding disparate sentencing for similar crimes.

Third, he favors allowing judges greater discretion to rein in the political overexpansion of the criminal law. He supports judicial discretion to impose lighter sentences and therefore endorses the Court’s decision in US v. Booker (2005) that essentially changed the federal sentencing guidelines from mandatory rules to advisory recommendations. By the same logic, I believe Stuntz would have opposed legislation imposing mandatory minimum penalties.

Fourth, Stuntz clearly would limit the scope of prohibition and the severity of punishment for the possession or use of drugs. Such amendments would reduce discrimination against black defendants, diminish the severity of the entire system, and make it more difficult for prosecutors to obtain guilty pleas to serious crimes that they are not able to prove. Stuntz notes the same problem—guilty pleas to unprovable crimes—resulting from a prosecutorial practice of charging offenses that make the defendant eligible for the death penalty in order to bargain the defendant into accepting a life sentence. Because of the uniqueness of the fear of death, I find that prosecutorial bargaining chip particularly offensive since it seriously risks persuading an actually innocent defendant to plead guilty and to accept incarceration for his entire life. In my view, it should not be permissible.

For each of three reasons, Professor Stuntz’s account of the “collapse” of an overgrown system of criminal law enforcement is well worth reading. It is full of interesting historical discussion. It accurately describes the magnitude of the twin injustices in the administration of our criminal law. It should motivate voters and legislators to take action to minimize those injustices.

This Issue

November 10, 2011

The Real Deng

In Zuccotti Park

-

*

The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction (Holt, 2008). ↩