The day after the Russian parliamentary elections in early December, the Chinese publication Global Times, an English-language newspaper and website managed by People’s Daily, the official organ of the Communist Party official, ran an editorial on how little credit the West gave to Vladimir Putin’s Russia for becoming a democratic country. “Russia’s transition to democracy has cost it dearly,” the editorial said, attributing a lot of Russia’s problems, including its failure to achieve prosperity and its “brutal wars” in Chechnya, to its adoption of a “Western-style election with a multi-party system.” The lesson is clear. China shouldn’t make the same mistake of trying to curry favor with the West by becoming a multiparty democracy itself. “The West doesn’t really have an interest in promoting democracy to the world,” the editorial avers. “Its scheme is to expand its interests hidden behind that process.”1

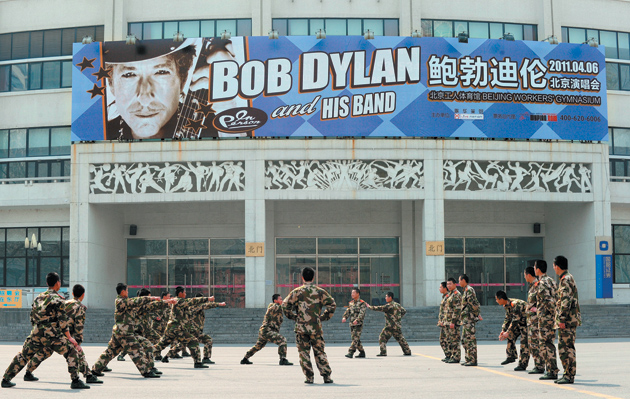

It doesn’t take a very deep survey of the Chinese press to find the theme that the real goal of American policy toward China, and in particular its criticism of the country for such matters as the imprisonment of dissidents, is a subversive one—to undermine the legitimacy of the ruling authorities, and thereby to obstruct China’s rise to great-power status. Last June, to give another example, China Daily, another English-language newspaper reflecting what China would like foreigners to read about it, carried an editorial entitled “Subversion in a Suitcase,” which held that the United States is creating “secretive cell phone networks” to help people circumvent government control of their electronic communications, an effort framed as support of “free speech and human rights” but whose real purpose is to help opposition forces “overthrow their legitimate governments,” thereby enabling the United States to “maintain…global dominance.”

The Chinese interpretation of American behavior may seem defensive and a touch paranoid, but there’s more than a grain of truth to the main point. After all, the long history of American criticism of China for human rights violations and its implied wish for China to become democratic amount to a demand that the country’s leaders give up their monopoly on political power, which, in their view, is akin to wishing for regime change.

This has frequently produced a certain amount of tension in the Chinese–American relationship, though rarely has the level of distrust seemed quite as high as it has in the past few months, as the United States and some other countries have observed that China is in the midst of one of the harshest repressions of domestic dissent in its recent history. It has also engaged in unusually bellicose behavior in the territorial and other disputes it has with other Asian countries, including American allies like Japan and the Philippines. For example, it has declared the entire South China Sea, one of the most important shipping lanes in the world, to be one of its “core interests.”

At the same time, China has been the main protector of regimes now under sanctions by the United States and the West, whether Iran, Sudan, or Zimbabwe, even as it has courted foreign leaders who have been branded as pariahs. At the end of this past June it accorded a warm welcome to Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, even though Bashir has been indicted for crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court, which wants him arrested.

The view has emerged among American commentators that China’s growing self-confidence, sustained in part by its emerging largely unscathed from the financial crisis of 2008, has made its leaders more certain of the path they’ve chosen for China, including its one-party system, and more defiant and publicly angry over criticism than they have been in the past. The solution to the mood of mutual animosity, according to Chinese commentators, is relatively simple. It’s for the United States to stop acting to impede the country’s “peaceful rise” to great-power status. As Wu Xinbo, the deputy director of the Center for American Studies at Shanghai’s Fudan University, wrote in June, “If the United States eases its policies toward China’s core interests, this could, in turn, encourage China to respect US core interests and foster cooperation as China’s material power and international influence are both growing.”

Many China experts in this country would more or less agree with that statement. Certainly it has been a strongly held view among some prominent American China experts that carping about human rights and about China’s domestic policies has chilled the atmosphere even as it has failed to help the victims of Chinese repression. These experts have tended also to be dismissive of what has come to be called the “China threat theory,” the notion that as China grows in power it will inevitably challenge American supremacy in Asia; that notion, they say, is panicky and overwrought, reflecting a false cold war analogy. China, after all, unlike the former Soviet Union, is not a missionary power eager to spread its ideology to other countries. It doesn’t arm rebels striving to overthrow pro-Western governments. It is an economic success and it wants to stay that way, in part by avoiding a conflict with the United States. In other words, China’s rise is a big event in world history, but the United States has no real strategic conflict with it and while it may be prickly and uncooperative at times, there’s no reason for either country to see the other as an enemy.

Advertisement

Is that view still tenable, if it ever was, or does China’s recent behavior signal a definitive departure from a sometimes contentious but essentially cooperative relationship with the United States to one of real enmity? In A Contest for Supremacy: China, America, and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia, Aaron L. Friedberg provides the most informed, cogent, and well-developed warning of the Chinese threat that I have seen. Friedberg is a former adviser to Vice President Dick Cheney and now a professor at Princeton recently appointed to Mitt Romney’s foreign policy team, focusing on Asia and the Pacific. He says that he is not a “card-carrying member of the China-watching fraternity,” which he believes to be guilty of a certain complacent optimism regarding China, a tendency to take its soft and reassuring rhetoric about its “peaceful rise” at face value. Friedberg’s view is this: “The United States and the People’s Republic of China are today locked in a quiet but increasingly intense struggle for power and influence, not only in Asia but around the world.”

It is a contest, moreover, that “we are on track to lose.” Because of China’s naval and missile development, in particular, Friedberg says, “the military balance in the Western Pacific is going to start to tilt sharply in China’s favor.” This would make it more difficult for the United States to extend its security guarantees to Japan, Korea, and other US allies. That in turn could lead to a “bandwagoning” effect in China’s favor such that eventually we too “would likely feel compelled to seek an accommodation with China and to acknowledge it as the preponderant regional power.”

This is a threatening development, Friedberg argues, somewhat abstractly, because it has always been an axiom of American foreign policy “to prevent the domination of either end of the Eurasian landmass by one or more potentially hostile powers,” which could deny the United States “access to markets, technology, and vital resources.” Why is China a potentially hostile power? Friedberg’s answer to that question gets to the crux of his thesis. It is China’s status as an opaque, secretive, corrupt, self-perpetuating, one-party state that makes it a danger to the United States, and vice versa. “The United States,” Friedberg writes,

aims to promote “regime change” in China, nudging it away from authoritarianism and toward liberal democracy, albeit by peaceful, gradual means…. It is largely because [China’s leaders] see the United States as the most serious external threat to their continued rule that they feel the need to constrict its military presence and diplomatic influence in the Western Pacific, pushing it back and ultimately displacing it as the preponderant power in East Asia.

Friedberg’s corollary assumption is that if China did become more democratic, then the contest for supremacy very likely wouldn’t take place. A democratic China, he says,

would certainly seek a leading role in its region…. But it would be less fearful of internal instability, less threatened by the presence of strong democratic neighbors, and less prone to seek validation at home through the domination and subordination of others.

China, of course, would strenuously deny any intention of dominating and subordinating other states—Tibet, Xinjiang, and Taiwan being, in its fiercely held view, parts of historic China. And indeed, contrary to Friedberg’s vision of things, China, with the important exception of the islands and atolls of the East and South China Seas and some minor areas on its Indian frontier, does not have any territorial quarrels with other countries and no discernible ambition to expand its own boundaries.

Over what particular issue then would Friedberg’s contest for supremacy be waged? A decade and a half ago the answer to that question among the theorists emphasizing a Chinese threat was Taiwan, where pro-independence forces seemed poised to take power, while China carried out missile-firing exercises off the island’s coast in an attempt to intimidate them. (The pro-independence party won Taiwan’s presidential elections in 2000 and 2004 but made no formal effort to split from the mainland.) China continues to build up an enormous arsenal of mobile medium-range missiles pointed at Taiwan, which is a powerful reminder that the island could be obliterated if it defies Beijing’s wishes. But in recent years, Taiwan’s pro-independence forces have been voted out, even as a thriving and multifarious economic relationship with China has continued to grow. A war over Taiwan seems less likely now than at any time since the Communists came to power sixty-two years ago.

Advertisement

A more likely area of contention now is the South China Sea, where China has two goals: one, to safeguard the sea lanes, which, from its point of view, could be threatened because of Beijing’s tense relations with nearby countries like Vietnam and the Philippines, and two, to gain control of reefs, atolls, and islands claimed by several Southeast Asian countries as well as China and presumed to be rich in oil and gas. Here is one region where the steady build-up of China’s navy is worrisome both to Friedberg, who describes it in considerable detail, and American military planners. In Friedberg’s view, China doesn’t aim to overtake the United States in naval prowess or to confront it directly, but to build its forces sufficiently to deny American forces access to regional waters in case of conflict. “Unless it acts soon to counter recent Chinese advances,” Friedberg writes, “the United States will find it increasingly dangerous in a future crisis to deploy its air and naval forces across a wide swath of the Western Pacific.”

As part of a military build-up that has seen large annual increases in expenditures for the past twenty years, China has built a “constellation of reconnaissance, communication, and navigation satellites that permit it” to hit targets “anywhere in East Asia.” It can track enemy surface ships hundreds of miles out to sea and is installing underwater listening devices capable of tracking American submarines. Its network of medium-range ballistic missiles “will soon give it the option of hitting every major American and allied base in the region with warheads.”

China is also set to deploy land-based anti-ship ballistic missiles that could use space-based tracking systems to hit aircraft carriers—“the tip of the spear of America’s unique ability to project power”—even hundreds of miles from China’s coast. These anti-ship missiles, Friedberg argues, would be a “‘game-changer’…fundamentally altering the balance of power in the Western Pacific.”

China of course began its military modernization from a position very far behind the United States; ten or fifteen years ago, almost all military analysts were derisive about China’s military strength. As recently as six years ago, Robert Ross, in a study of China’s security needs, analyzed whether recent Chinese modernization involved any basic strategic change with respect to the United States, and his answer was a resounding “no.” The consequences of any actual combat between China and the United States, he concluded, would be “devastating” for China, which would lose its entire surface fleet, suffer irreparable economic harm, and lose its access to Western technology. The inevitable loss of a war with the United States would, in addition, be such a blow to the standing of the ruling party that it could well collapse.2

Moreover, the United States is highly unlikely to be unresponsive to China’s looming naval strength. Friedberg reports, for example, that the Obama administration has for some time adopted policies aimed at “balancing” the growth of Chinese power; it is reinforcing military cooperation with other Asian countries, including Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam, as well as deploying more long-range attack submarines in the Western Pacific and enhancing cyber-war techniques.

Indeed, the irony is that since his book was written, the current Democratic administration has undertaken the tougher line on China that Friedberg recommends. In November, President Obama announced that the United States would station 2,500 troops in northern Australia, a move that aroused an irritated response in Beijing. He sent Hillary Clinton to Burma to encourage that country’s modest steps toward freedom and away from being a vassal of Beijing. And during a meeting of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in Indonesia in November, the United States was among sixteen of the eighteen countries present that voiced criticism of China’s way of handling the South China Sea dispute.3

Still, China is much stronger and much richer than it was before, and, given its growing economic power, it is going to continue getting stronger. This will mean ever greater costs for the United States in both money and political will if it is to maintain its military superiority and to avert what Friedberg thinks would be ruinous: a quiet withdrawal as the great power in Asia. If, as Friedberg asserts, China’s goal is “to displace the United States as the dominant player in East Asia, and perhaps to extrude it from the region altogether,” a world-class naval arsenal would be a very useful instrument.

But is China’s goal really to exclude American power from the region, or is it something more modest than that? In fact, questions can be raised about Friedberg’s thesis at every turn, and no doubt will be by Friedberg’s rivals in the pro-engagement camp of China experts. Certainly one major counterargument is that while China has grown at an astonishing rate and become more powerful in the past twenty years, it faces domestic problems of such magnitude as to render virtually ridiculous the idea that it has global ambitions or that it can achieve them.

This view has changed somewhat, though not fully in the direction of Friedberg’s arguments. In a much-noted article at the end of 2010, for example, Elizabeth Economy, a senior China analyst at the Council on Foreign Relations, wrote that China has relinquished its foreign policy pose of “hide brightness; cherish obscurity,” in favor of a far more aggressive and worrisome “‘go out’ strategy designed to remake global norms and institutions” and to advance its interests more boldly and aggressively than ever before.4

But Economy and others have also measured the staggering costs of China’s growth as well as the equally extraordinary scope of what it plans for the future, whether its high-speed train network or the proposed channel to transport water the thousand miles or so from the Yangtze River to the Beijing-Tianjin megalopolis. On the cost side are ruinous pollution, corruption that extends into every aspect of personal and national life, and very widespread social dissatisfaction stemming both from the pollution and the corruption.

These costs of development have provoked levels of social discontent that seem unprecedented even in a country that half a century ago experienced the largest famine in human history. China officially admits to some 90,000 protest demonstrations taking place across the country every year, which is close to 250 per day. No doubt some are quite small but they are increasing. In a recent talk at the National Committee on United States–China Relations in New York, Kenneth Lieberthal, a China expert at the Brookings Institution, cited a series of internal social surveys conducted in the past year in China showing “that economic growth is no longer cutting it.” Formerly, he said, the government was able to assume that as long as it was able to engineer steady increases in China’s GDP, the ills of corruption and pollution would be accepted as part of the cost of the general welfare. But now, he said, “people are growing angrier at the government and losing trust in the government…and [the government] doesn’t know what to do about it.”

Of course, what China’s leaders have done, especially in the wake of the Arab revolt, is step up the country’s already high level of political repression, and this is a reminder of Friedberg’s root assumption that the present and future “contest for supremacy” with China lies in its authoritarian ideology and in the perception of China’s leaders that the United States is out to overthrow them. “As seen from Beijing,” Friedberg writes, “the United States is a dangerous, crusading liberal quasi-imperialist power that will not rest until it imposes its views and its way of life on the entire planet.”

No doubt China’s leaders are mightily annoyed by the moralistic imperialism of the United States. Whether they actually see it as the sort of existential threat suggested by Friedberg is highly questionable. Friedberg’s stress on American hostility to China’s police state is in this sense puzzling. Paradoxically, it seems to put him into the camp of his policy rivals, the advocates of more engagement and less complaint about human rights who do not believe that there is a genuine strategic conflict between China and the United States. The logical implication of Friedberg’s argument would seem to be that the “contest for supremacy” is a product of the American tendency to engage in “subversion in a suitcase” and not of some intrinsic great-power conflict, which, of course, is exactly what some members of the engagement camp as well as writers like Wu Xinbo have been arguing. This is probably not Friedberg’s intended implication, and yet the lack of clarity on this point is a puzzling weakness in his book.

In many ways indeed it would be reassuring if the greatest danger of conflict between China and the United States did derive from China’s authoritarian nature, rather than from an intrinsic and unavoidable conflict of practical interests, a possible territorial clash, or some Chinese move to dominate or intimidate other countries in the region, thereby prompting an American response. Friedberg gives some consideration to the possibility that if China were to be more democratic, things might actually be worse for the United States. A more democratic China would be less able to restrain public tendencies toward a kind of aggrieved nationalism, with their components of anti-American and anti-Japanese sentiment. In addition, as some China experts have written, even if China were to become, miraculously, a liberal democracy, it wouldn’t relinquish the strategic interests it has in such areas as Tibet, Xinjiang, and even the South China Sea.5

The military buildup that worries Friedberg would surely be taking place even if the United States did not hector China on human rights, since it is aimed at achieving several goals, including keeping Taiwan from declaring independence, intimidating Japan, and protecting its access to natural resources. China’s keen interest in atolls and islands much closer to the Philippines and to Vietnam than to China itself derives from the 28 billion barrels of crude oil that the US Geological Survey has estimated lie under the waters near them, in addition to large deposits of natural gas. Likewise, China’s reluctance to impose sanctions on Iran or Sudan and the red carpet it rolls out for the unsavory likes of Omar al-Bashir are related to its ravenous appetite for oil and other raw materials to fuel its growth, a need it would have no matter what form its government took.

Still, Friedberg is surely right that a rising dictatorial power is almost inevitably more dangerous and more difficult to deal with than a rising democratic one. And that raises the question whether China might yet move away from the Leninist party-state toward something less authoritarian, which, in Friedberg’s scheme of things, would change everything. He offers very little hope of this happening, arguing that the ruling party is a vast, multi-armed organization, with numerous means of keeping a tight grip on power and many reasons not to loosen it. Friedberg concludes that despite years of predictions that economic growth would lead to political reform, the one-party state in China is there to stay. Certainly China’s leaders will deploy their vast resources of police power, censorship, and propaganda to assure that it is.

Friedberg may be right about this, but he may also be overly pessimistic. China Daily may rail against “the arrogant tendency” of the United States “to act as self-appointed guardians of human rights in other parts of the world,” but the very strenuousness of the regime’s efforts to try to stamp out dissenting views on human rights is a recognition that there is a constituency for these views. When the now imprisoned Nobel Peace Laureate Liu Xiaobo circulated his Charter 08 petition calling for multiparty democracy, the document was signed in a rather short time by some 10,000 people, including some officials, which is no doubt one reason why Liu was imprisoned for “inciting state subversion.” Elizabeth Economy points out that the future urban culture of China, like urban cultures everywhere, will be likely to yearn more for intellectual and cultural freedom than China’s shrinking rural society. Neither Economy nor Friedberg can be confident that this will or will not occur, but it would also be wrong to rule it out.

In the end, Friedberg’s book is not entirely persuasive on his essential points: that China’s goal is to supplant the United States in Asia, that it is winning the contest for power and influence there, and that it is the very nature of the United States as a champion of antiauthoritarian ways that is at the crux of the conflict. At the same time, his book lays down some serious challenges to partisans of engagement, especially the notion that graceful yielding to China’s sensibilities and interests will lead it toward responsible and moderate global citizenship. There is, quite simply, something menacing in the rise to great power of a country as big, ambitious, opaque, and intellectually controlled as China, with its inclination to bully smaller countries in its neighborhood (not to mention Taiwan, Tibet, Xinjiang, and Chinese dissidents), its cultivation of grievances toward the rest of the world, and its propaganda department’s control over the truth itself.

A big part of the challenge posed by China is the success that it has had in presenting an alternative to the democratic values and practices that the United States and other countries advocate. Two decades ago, with the fall of the Soviet Union, the conviction became almost universal that for a country to be successful, it had to follow the “free-market” democratic model. Notwithstanding China’s harsh treatment of dissidents and its single-party rule, its impressive growth, its investment in technology, its foreign exchange reserves, its awesome infrastructure development, and the other features of its state-planned progress are an implicit demonstration that the Western model isn’t the only workable one, especially at a time when the West is experiencing its own unplanned economic crisis. This is a notion as common in the Chinese press as the notion that American concern about rights is just an excuse to maintain global dominance. “An embattled West has been caught unprepared by a defiant but practical China,” a columnist in Global Times exulted recently. He might be right.

-

1

“Russian Democracy Receives Little Applause,” Global Times, December 5, 2011. ↩

-

2

Robert S. Ross, “Assessing the China Threat,” The National Interest, Fall 2005. ↩

-

3

Jackie Calmes, “Obama and Asian Leaders Confront China’s Premier,” The New York Times, November 19, 2011. ↩

-

4

Elizabeth C. Economy, “The Game Changer: Coping with China’s Foreign Policy Revolution,” Foreign Affairs, November/December 2010. ↩

-

5

See Andrew J. Nathan, “The Great Debate,” nationalinterest.org, June 22, 2011. ↩