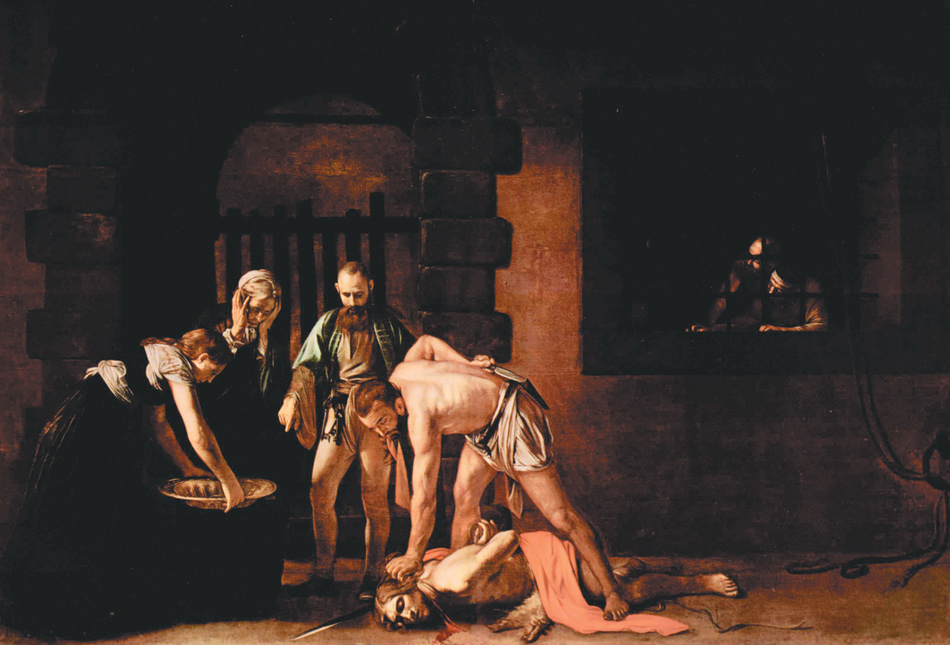

In 1996, the huge altarpiece Caravaggio painted in 1608 for the Oratorio di San Giovanni in Malta was brought to Florence for restoration at the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, because five years before it had suffered two slashes from the knife of a demented attacker. For someone who had never been to Malta and seemed unlikely to travel there, this provided a unique opportunity: the damaged painting was first put on public display in the Sala del Cinquecento of the Palazzo Vecchio, and then, some five years later, the beautifully restored canvas was again exhibited, this time in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine, directly across from the Brancacci Chapel.

Both times, it was possible to make repeated visits to contemplate this altarpiece depicting the beheading of the prostrate John the Baptist by Herod’s executioner and to examine it from much nearer than one ever could in the Oratory. In both the Palazzo Vecchio and the Carmine it stood on the floor, and it was possible to come almost close enough to touch the vast canvas, nearly twelve feet high and seventeen feet long. It made its greatest impact, however, if one stood farther away, so that one could encompass the image in its entirety, with its unconventional but assured composition and its breathtaking mastery of light and shadow, and imagine how it must extend the space above the altar in the Oratory (for the canvas has the same dimensions as the end wall of the Maltese chapel).

There is a theatrical quality to this picture, as if one were witnessing a frozen moment of an opera or a play, a tableau vivant, yet at the same time one is aware that its significance is far greater than merely histrionic. For there is something profoundly, ineluctably, ineffably moving about the tragedy depicted in this dimly lit, eternally resonant scene: once experienced, it can never be erased from the mind. Even today, when I summon it to my memory, I can palpably feel the immense, dark stillness that suffuses this miraculous work of art, one of the greatest paintings in the world.

The story of who painted this masterpiece, why it exists in remote Malta—where Caravaggio briefly was a member of the the Order of St. John—and how it represents such a revolutionary moment in the history of art has repeatedly been told; for Caravaggio has inspired biographers and critics from the very beginning. As early as the first half of the seventeenth century, only a few years after his death, two people who had known him personally, one of them an angry, bitter rival, wrote the first biographies of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Since his critical rehabilitation by Roberto Longhi and others just after World War I, the story of the triumphs and vicissitudes of Caravaggio’s posthumous reputation across the centuries has also been told many times. In only the past fifteen years, I count at least fifteen biographies in various languages. And all modern biographies seem to share the same somewhat peripheral preoccupations: (1) documentary evidence, mostly from police blotters, of what Longhi called Caravaggio’s “temperamento senza freni” (“unbridled temperament”); (2) the identities of his models; (3) the prostitutes he knew—Fillide Melandroni, Anna Bianchini, Lena Antognetti, Menica Calvi (“Menicuccia”); (4) the identification of self-portraits in his canvases; and (5) Francesco Boneri (“Cecco”), Caravaggio’s assistant and, quite probably, his catamite. None of these items is without interest, but none helps us much to experience the paintings.

In view of so much biographical publication, one may reasonably ask what a new biography can possibly hope to add. Andrew Graham-Dixon acknowledges his significant debt to Helen Langdon’s fine biography1 published twelve years before his own, calling it “much the best twentieth-century biography of Caravaggio.” In the interim, however, several archival discoveries have given us new facts and the opportunity for revised conjectures, especially about the film noir of Caravaggio’s tempestuous last years in Naples, Sicily, and Malta, and Graham-Dixon makes full use of these documents.

He has also benefited greatly from the authoritative scholarship of Professor Wietse de Boer on Archbishop Carlo Borromeo and his spiritual dominance over the Milanese world of Caravaggio’s youth.2 The section of Graham-Dixon’s biography devoted to the influence on Caravaggio of Borromean piety and the art of the sacro monte (“holy mountain”—a series of chapels on a hillside, created in the late Renaissance, in which various biblical scenes are depicted in painting and sculpture) is one of his most illuminating.

Like all Caravaggio scholars, Graham-Dixon has his own carefully considered view of what constitutes the corpus of Caravaggio’s work, and it is reassuringly conservative in comparison with the optimistic liberality of several scholars active in Italy today. And then, of course, there is his personal, sometimes idiosyncratic, interpretation of the individual paintings, which he describes as “my principal focus throughout.”

Advertisement

He has thought carefully and intelligently about each of the paintings he is willing to attribute to Caravaggio, and often his descriptions are informative and suggestive. Yet for me at least, his ambitious efforts sometimes have a tendency to go one paragraph farther than I am able to accompany him—and he sometimes sees things I can’t. I cannot, for example, believe that the lizard biting the boy is “the very image of the vagina dentata” or that the lad’s clothing “might be…a twisted bedsheet.” In an unnecessary effort to convince us that Caravaggio had sexual feelings about women, he claims that the Saint Catherine of Alexandria in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, for whom the prostitute Fillide posed, “simmers with violent sexuality,” “encapsulates…intense and powerfully inverted eroticism,” and portrays “a sexy modern girl”; I must confess my inability to perceive any of that in the painting. The ceiling Caravaggio painted for the casino of Cardinal del Monte’s Villa Ludovisi in Rome with the mythological figures of Jupiter, Neptune, and Pluto is hardly the “bawdy fantasy of airborne larking about” that Graham-Dixon thinks it is, nor is Pluto’s “emphatic phallus” emphatic: it’s just a penis.

The young man counting his coins in the great Calling of Saint Matthew in Rome’s San Luigi dei Francesi does not remind me of Judas Iscariot and his thirty (not “fifty”) pieces of silver, nor do I believe that the group sitting around the table “has been calculated to resemble a profane version of the Last Supper”; neither does the overwhelming, looming horse in the Conversion of Saint Paul in Rome’s Santa Maria del Popolo make me think of “the manger in which Christ was born.” And I very much doubt that the profoundly touching Adoration of the Shepherds in Messina is “an uncanny allegory” of the artist’s own birth in Milan in 1571, in which Joseph and the shepherds “are Caravaggio’s father, his uncles, his grandfather.”

The most egregious of these over-the-top readings is that of the Martyrdom of Saint Ursula in Naples, one of the very last paintings Caravaggio did. Graham-Dixon says it depicts the fact that a Hun “has just shot Ursula at point-blank range in the stomach,” and he goes on to make the dramatic claim that “her swollen belly has been impregnated [italics mine] by the tip of an imperfectly painted arrow” and that, in response, Saint Ursula makes “a gesture with her hands that suggests she wants to part the flesh of her stomach still further. She is about to give birth to her own death.” The chief problem with this heady description is its anatomical confusion, for the painting clearly shows the arrow entering not her stomach but the cleavage between her breasts, in quite a different province of the body from the birth canal.

Graham-Dixon derives much of his account of Caravaggio’s important Roman years (1592–1606) from Helen Langdon, but he also gives his own vivid evocation of the Rome in which Caravaggio lived, painted, and quarreled—the world that supplied him with the popolano figures of his paintings. It is the demimonde of Thomas Nashe and Thomas Dekker translated into Italian: a universe thronged with swaggering youths and pox-ridden doxies, pickpockets and con men, pimps and procuresses, beggars, drunks, and roaring boys in a sordid ambiente of noxious stenches, insalubrious lodgings, slashed faces, and salacious pasquinades. It’s interesting to remember, however, that in other respects it is also the more sophisticated Rome of ecclesiastical nobility in which Joachim Du Bellay had lived for almost five years in the 1550s and that Montaigne visited and described ten years after Caravaggio’s birth.

Surprisingly, Graham-Dixon seems somewhat discomfited by Caravaggio’s homoeroticism. Sometimes he frankly acknowledges it, but at other times he does his best to minimize or mitigate it. Cecco, Caravaggio’s servant boy and model, seems to embarrass Graham-Dixon; for although he admits that there are indications that they probably slept in the same room, he primly insists, on the basis of no evidence whatsoever, that “Cecco certainly had his own separate bed, or mattress.” His early description of Caravaggio’s sexual inclinations is characteristic: “The balance of probability suggests that Caravaggio did indeed have sexual relations with men. But he certainly had female lovers.”3

No doubt he did. Our modern categories of homosexual and heterosexual are almost irrelevant for earlier ages, when sexual preference was much less strictly pigeonholed. In Caravaggio’s day, attitudes toward sexuality were far less discriminative and draconian. It seems likely that Caravaggio slept with whoever was available, male or female, yet it also seems undeniable that he was most turned on, not by men, as Graham-Dixon repeatedly says, but by adolescent boys. There is even evidence from an obscure Messinese painter named Francesco Susinno that he stalked playgrounds, like any modern pedophile. (“The teacher became suspicious and wanted to know why he was always around.”)

Advertisement

But Graham-Dixon is so eager to insist that his subject had sexual experiences with women that a statement to police in 1605, which refers to the prostitute Lena Antognetti as “donna di Michelangelo” (“Caravaggio’s woman”) and surely indicates that she was his sexual partner, causes him to go so far as to speculate at length on the possibility that Caravaggio might have been “a part-time pimp.” This seems unnecessarily fanciful. My own guess is that Lena was simply his Patti Smith.

Graham-Dixon is excellent in describing what Italians term the pauperismo of Caravaggio’s work, symbolized by the notorious dirty feet of the Paris Virgin Mary and those of the executioner of Saint Peter in Santa Maria del Popolo; and his discussion of the two versions of Saint Matthew and the Angel, executed to be placed over the altar in the Contarelli Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi, is exemplary, except that the image of the second version has unfortunately been printed in reverse in his book. The far greater but rejected first version, which was in a Berlin museum and was destroyed during World War II, was one of the most affectingly intimate pictures Caravaggio ever painted, but its illiterate peasant saint in his sturdy bare feet was much too avant-garde for the congregation of San Luigi dei Francesi and, in the words of his early biographer and rival, “pleased nobody.”

Graham-Dixon’s analysis of the Dublin Betrayal of Christ, rediscovered only in 1990, is both sensitive and informative, as are his descriptions of the two versions of The Supper at Emmaus, one in London and the other in Milan, the first (1601) theatrically lit and explosively agitated, the second (1606, Brera, Milan) more somber and grave, restrained and spiritual. Throughout, his discussions of Caravaggio’s revolutionary use of chiaroscuro and realistic depictions of humble poverty, and his careful analysis of the artistic advances made by the artist in these fourteen definitive Roman years (1592–1606) will be useful to anyone encountering these works for the first time, for his descriptions are scholarly, informed, and often insightful.

Sometimes, however, their excesses cause them to miss the point. There is a striking example of this in the description of the wonderful but infamous Saint John the Baptist (1602) now in Rome’s Capitoline Museum. As usual, Graham-Dixon is chary of the sexual and eager to confer a more elevated, more spiritual and intellectual, significance than may accurately be warranted:

Those who have seen the Capitoline St John as a daringly sexual depiction of a Christian saint, laughing provocatively as he turns to face the viewer, miss the point of the picture entirely…. His ignudo is no sleepy, sensual emblem of a vanished golden age, but an ecstatic prophet bathed in the light of divine revelation. The naked, rejoicing boy embraces the animal by his side because it has been sent to him by God to show him what will come to pass. He sees in it the destiny of Christ the saviour, with whose fate his own is intertwined, and whom he will one day baptize….

In his mind’s eye, he is looking into the future, seeing Christ’s blessed death and the salvation of mankind. That is the reason for the smile on his face. It is the beatific smile of a mystic, a seer.

But compare this to an earlier, far more subtle and incisive analysis of the same painting, from the most brilliant essay I know on Caravaggio, by the late Sydney Freedberg:

Caravaggio’s apprehension of the model’s presence seems unimpeded in the least degree by any intervention of the intellect or by those conventions of aesthetic or of ethic that the intellect invents. The image Caravaggio presents to us is essentially the sensuous perception of a physical fact; the psychological record accompanying it is only such as is required to imply the meaning that this sensuous presence may have for the viewer.

This presence is of an aggressively naked youthful male, and in the context of our biographical information about Caravaggio and our understanding of the pictures he painted prior to this one, we recognize that this image is homosexual in its essential content. One might juggle with platonic notions of the picture’s sense or try to palliate the subject by lending it an Old Testament or even a mythological rather than a Christian label, but it is most likely that none of these was meant.

In any case, the nominal subject matter is of no more than tangential import, since the real meaning and the nominal theme diverge from one another: the Baptist with the sacrificial ram, or whatever other subject may be proposed instead for it, is merely a figleaf imposed upon the real meaning of this picture.

The real theme is not a narrative, an allegory, or an emblem; it is a presence, and the meaning of the presence is the sheer sensory experience of it and the emotions this experience is meant to generate…. There is no precedent for this degree either of intensity or directness in any prior art.4

When you look at the naked portrait of Cecco as John the Baptist in the Capitoline Museum, which is the painting you see, Graham-Dixon’s or Freedberg’s?

The fugitive desperation of Caravaggio’s last four years, after his murder of Ranuccio Tomassoni on May 28, 1606 in Rome, is recounted with all its inherent drama by Graham-Dixon, who uses the latest archival discoveries for his descriptions and conjectures. First, the flight into the Alban Hills and then to Naples; then Caravaggio’s attempt to take refuge in Malta; his escape from imprisonment in Valletta to Siracusa, Messina, and Palermo in Sicily; his return, pursued, to Naples; the serious wounds he suffered in a vicious attack at the Osteria del Cerriglio; and his lonely death on a beach of the Argentario as he tried in vain to get back to Rome.

One wonders how Caravaggio found either the time or the strength to paint in these frantic, frightened years, and indeed, although a number of his last paintings are masterpieces, others present problems. We have some sixteen paintings from this period, and we know of one Neapolitan altarpiece that has been destroyed and one Sicilian Adoration stolen by the Mafia. Some of the paintings are drained of color and claustrophobically overcrowded; some are thinly or even cursorily painted. The sleeping baby in Palazzo Pitti, whatever iconographical interpretations of importance one may give it, remains a repellent picture.

One of the saddest paintings I know is the last Saint John the Baptist, now in the Galleria Borghese in Rome, painted during his second stay in Naples and possibly the last painting Caravaggio did. It is one of three paintings he had with him at Porto Ercole when he died. Unlike his earlier Saint Johns, this boy is thin and emaciated, shrouded with the pallor of illness and death, the wasted denizen of a world of pleasure that has lost all joy.

To my surprise, the aspect of Caravaggio’s work that means the most to me seems to be mentioned only rarely by the scholars who write about him. What I find most deeply moving in his paintings is not his incomparable skill as a painter, not his original way of using light and darkness, not his rejection of maniera nor his complex relationship with Michelangelo, not his impressive skill at painting alla prima (directly onto the can- vas, without preparatory drawings), not his affecting pauperismo, not his dramatic compositions, but his pervasive compassionate empathy. I don’t just mean his ability to depict compassion, as he does on the face of the early angel supporting Saint Francis in ecstasy or, more subtly and more tenuously, on the late face of David staring at the head of Goliath in the Galleria Borghese. What I’m referring to is Caravaggio’s truly extraordinary ability to imagine sympathetically what it must be like to be another person, saint or sinner, woman or child, knight or jailer, usually in circumstances he could never himself have known.

There is a story, whose source I’ve been unable to find, about Tolstoy and Chekhov taking a walk one spring morning at Yasnaya Polyana, when they encountered a horse in the woods. Tolstoy started talking about the horse, graphically imagining what the animal would think about the clouds overhead, the umbrageous trees, the smell of the wet earth, the flowers, the sun. Chekhov, astonished, exclaimed that Tolstoy must have been a horse in an earlier life, because only a horse could know so completely what a horse would feel. Tolstoy responded, “No, but the day I came across my own inside, I came across everybody’s inside.”

With similar assurance, one might claim that only a horse could have painted the great steed that dominates The Conversion of Saint Paul. For Caravaggio’s encompassing imagination knew no limits. His powerful capacity for sympathetic understanding enabled him to inhabit the most alien scenes and become the actors in them. He even knows exactly what it must feel like to have your head cut off. The individuals who people his canvases have faces we may encounter going home on the subway tonight, or perhaps they have already passed us this morning in the street. And each of these faces identifies a very specific person, revealing his anxieties and hopes, his likes and dislikes, his failures and triumphs.

Like Tolstoy, Caravaggio somehow understood everyone’s inside: the tender solicitude of a lovely young mother helping her naked child to learn to walk; a rent boy with no illusions left, proffering temptation in the guise of Bacchus; Judith, boldly determined in her murderous vindictiveness; the wily deception of a gypsy woman enchanting a gullible fop; Judas, fearful he may be making a mistake but resolute in evil; a bewildered innkeeper who doesn’t realize his guest has just risen from the grave; the sadistic ferocity of the flagellant, hair-pulling jailer; the innocent, uncomprehending boy, puzzled that a stranger should summon the tax-collector; the mother of Jesus, her face numb and expressionless with loss as his lifeless body is lowered into the tomb, witnessing what she always knew she would one day see.

Caravaggio’s genius for empathy is not merely Tolstoyan; it is Shakespearean in its magnitude.

-

1

Caravaggio: A Life (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998). ↩

-

2

Wietse de Boer, The Conquest of the Soul: Confession, Discipline, and Public Order in Counter-Reformation Milan (Brill, 2001). ↩

-

3

Cf. “Caravaggio was capable of being aroused by the physical presence of other men…. But he was equally attracted to women.” And: “He kept company with whores and courtesans…, and on the evidence of his paintings he was equally alive to the physical charms of men.” ↩

-

4

S.J. Freedberg, Circa 1600: A Revolution of Style in Italian Painting (Harvard University Press, 1983), p. 54. ↩