When his first short-story collection, Drown, was published in 1996, Junot Díaz was hailed as a writer who spoke to his readers from a world, and in a voice, that had never before appeared on the page. No one else had conveyed, with quite such immediacy, the experience of Dominican-Americans inhabiting two countries and two cultures without feeling entirely at home in either. No one had made us so acutely aware of the fact that, for a large segment of our population, immigration is not a singular event but a way of life involving travel to and from the homeland, journeys with the power to reawaken all the anticipation and terror of the initial departure.

Díaz’s work enabled, or obliged, his gringo audience to spend time in neighborhoods that in the past they might have sped through, on their way to somewhere else. And for all their raucous humor and genial high spirits, the stories in Drown thrummed with anxiety—an unease generated by poverty, racism, domestic tension, and sexual confusion. These stresses, one felt, might at any moment overwhelm Díaz’s characters, were it not for the consolations of storytelling: the relief of transforming anger and apprehension into narrative.

The Latino immigrant experience had been eloquently described by earlier novelists including Oscar Hijuelos, Sandra Cisneros, Julia Alvarez, and Cristina García. But what set Díaz apart from his predecessors was the exuberance with which he exchanged the standard diction of traditional fiction for the flashier, jazzier locutions of the urban barrio, with just enough Spanish to convey the flavor and rhythm of a hybrid language and without mystifying or excluding English-speaking readers. (Hedging their bets, Díaz’s British paperback publisher added a Spanish-English glossary.)

Drown takes its epigraph from a poem by Gustavo Pérez Firmat:

The fact that I

am writing to you

in English

already falsifies what I

wanted to tell you.

my subject:

how to explain to you that I

don’t belong in English

though I belong nowhere else

Obviously, language is a matter of crucial importance to every writer, but for Díaz—and for his homeboys selling weed on the streets of industrial New Jersey, his young men delivering pool tables to homeowners reluctant to leave them alone with the silverware, his immigrant mothers trying to protect their families from dangers that their children understand better than they do—every word involves a choice between past and present, campo and barrio, mercado and mall.

Reading Díaz, we understand why his bilingual characters continue to use street-slang Spanish long after they have stopped hanging around on the corner: for comfort, for community, as shorthand, and because there is no more expressive way to say what they want to say. Their vocabulary and their cadences, their casual obscenities and reflexive prayers define them.

Flipping from English to unitalicized Spanish, “Fiesta, 1980” transmits the alternating currents of warmth and tension at a family reunion, delivered along with mild jolts of the humor that enable Yunior to survive:

Papi came in from parking the van. He and Miguel gave each other the sort of handshakes that would have turned my fingers into Wonder bread.

Coño, compa’i, ¿cómo va todo? they said to each other.

Tía came out then, with an apron on and maybe the longest Lee Press-On Nails I’ve ever seen in my life. There was this one guru motherfucker in the Guinness Book of World Records who had longer nails, but I tell you, it was close. She gave everybody kisses, told me and Rafa how guapo we were—Rafa, of course, believed her—told Madai how bella she was, but when she got to Papi, she froze a little, like maybe she’d seen a wasp on the tip of his nose, but then kissed him all the same.

When Yunior, who narrates many of the stories in Drown and in Díaz’s new collection, This Is How You Lose Her, leaves his mother’s apartment for college and later for a university teaching job in Boston, every sentence becomes a coded pledge of allegiance: a declaration of where Yunior’s loyalties lie, from minute to minute, as he insists upon his right to stand with one foot in the ghetto and the other in the library stacks. It’s hard to think of another writer who could include, in a single paragraph, the words chill and Bartleby (referring to Herman Melville’s scrivener, responding to his employer’s every request with “I would prefer not to”) and use both nouns as verbs. “When I ask her if we can chill, I’m no longer sure it’s a done deal. A lot of the time she Bartlebys me, says, No, I’d rather not.”

Advertisement

The strongest of the fictions in Drown are sharply observed, sympathetic, and brave in their refusal to settle for sentimental resolutions. Like Isaac Babel’s “My First Goose,” Díaz’s “Ysrael” explores the ways in which violence against the innocent can ameliorate tension and boredom, and forge communal bonds. The title story is a moody evocation of the hot summer during which the narrator has a fleeting (“Twice. That’s it.”) and dissociated homosexual affair with a friend about to leave for college.

But other stories opt for easy charm over the hard labor of telling us how something looks, of convincing us that a character would do what the writer says he does, of turning a plot in directions that have us on the edge of our chairs, even if nothing dramatic is happening. By the time we’ve finished the book, we’ve most likely forgotten which girlfriend broke the narrator’s heart in which story. And there are passages of language that seem more like a flurry of tics than like revelations of individual consciousness. After enough characters have added the word ass to enough adjectives—“sharp-ass,” “skinny-ass,” “hairy-ass”—we may begin to wonder how much time we want to spend in their heads.

Upon rereading, Drown seems like the debut of a writer who could go in one of two directions. Either he could challenge himself to keep doing something more difficult and original. Or he could keep on doing what he does well, or well enough. One thinks of Picasso’s belief that the most dangerous trap facing the artist is the temptation to repeat himself; even plagiarism, he claimed, was preferable to repetition.

In Díaz’s first novel, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007), he pulled back from his tight close-up on Yunior to provide us with a panorama capacious enough to include history, geography, entire families and populations. Multigenerational, transnational, the story is told from several perspectives: from that of Oscar, the obese comic-book nerd, obsessed with science fiction, dreaming of becoming the Dominican J.R.R. Tolkien; his politically conscious, intelligent, and beautiful sister, Lola; his college roommate, Yunior, whom we recall from Drown and whose longing for love is perpetually at war with his impulse to cheat on his lovers; and a few of Oscar’s older relatives, who lived and died amid the horrors of the despotic Trujillo regime.

If Drown’s realism suggested that Díaz had distanced himself from the supernatural trappings that had become common in Latin American fiction, the novel embraces them; its plot is set in motion by an ancient Dominican curse. But unlike the spells that rearrange the destinies of the residents of Gabriel García Márquez’s Macondo, the hex that dooms Oscar Wao and his family isn’t cast by a local bruja or a vengeful discarded lover, but rather by Trujillo and the oppressive society he created.

In making this all-important change, Díaz transformed a familiar theme into a trenchant observation about the legacy of history. When a generation survives violence and repression, the next generation suffers, especially when it is uprooted and moved to a country that offers minimum-wage jobs and a less-than-warm welcome. Díaz has so much he wants to say about Trujillo that it spills over into footnotes, and younger readers who might never have heard of the Dominican dictator may be inspired to investigate further by passages like this one:

Not only did [Trujillo] lock the country away from the rest of the world, isolate it behind the Plátano Curtain, he acted like it was his very own plantation, acted like he owned everything and everyone, killed whomever he wanted to kill, sons, brothers, fathers, mothers, took women away from their husbands on their wedding nights and then would brag publicly about “the great honeymoon” he’d had the night before. His Eye was everywhere; he had a Secret Police that out-Stasi’d the Stasi…a security apparatus so ridiculously mongoose that you could say a bad thing about El Jefe at eight-forty in the morning and before the clock struck ten you’d be in the Cuarenta having a cattleprod shoved up your ass. (Who says that we Third World people are inefficient?)

The bouncy, conversational irreverence of the prose keeps the reader engaged, even when the characters are undergoing some tedious trial of the body or the spirit. Here, for example, is how Díaz describes the dead end that Oscar reaches when he returns to teach at the Catholic school he attended:

Had Don Bosco, since last we visited, been miraculously transformed by the spirit of Christian brotherhood? Had the eternal benevolence of the Lord cleansed the students of their vile? Negro, please. Certainly the school struck Oscar as smaller now…but some things (like white supremacy and people-of-color self-hate) never change: the same charge of gleeful sadism that he remembered from his youth still electrified the halls. And if he’d thought that Don Bosco has been the moronic inferno when he was young—try now that he was older and teaching English and history. Jesú Santa María. A nightmare.

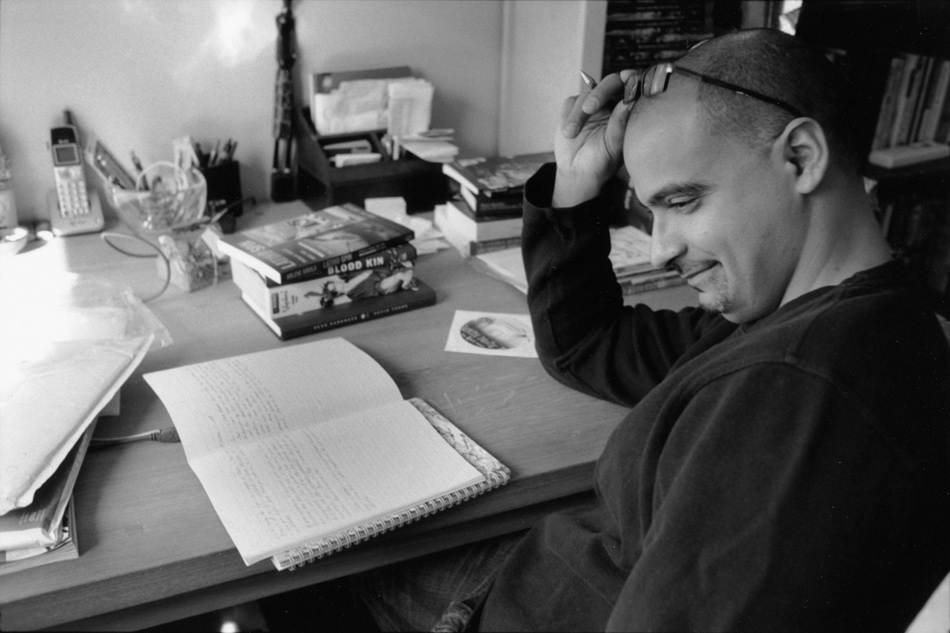

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, which received the 2008 Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award, has attracted a wide and passionate readership. And Díaz, who has just received a MacArthur fellowship, has become an important figure not only in the literary world but in the Hispanic immigrant community, to whom his success measures the heights that someone raised on the island and in the ghetto can achieve. One can imagine that this role, and the questions of authenticity it raises, exerts a special pressure on the writer. In interviews, Díaz describes himself as being, like his characters, still very much the kid who grew up in his New Jersey neighborhood. It seems important to him to establish that his connection with the raw material of his fiction is immediate, personal, and deeply felt rather than distanced and nostalgic—as if what gives him the right to write about these characters is that, on some level, he remains one of them.

Advertisement

Whatever one may think about the lyrics of the J-Lo song, “Don’t be fooled by the rocks I got, I’m still, I’m still Jenny from the block,” we can assume that Jennifer Lopez means every word. Likewise, it seems clear that Junot Díaz’s fiction and his public persona reflect a desire to remain true to his earlier self, his ghost self: Junot from the block.

In This Is How You Lose Her, Yunior, on a sort of failed honeymoon in the Dominican Republic, stays at a luxury hotel he calls “The Resort That Shame Forgot.” “Chill here too long,” he worries, “and you’ll be sure to have your ghetto pass revoked, no questions asked.” Yunior’s dilemma is that of a passionate reader with “an IQ that would have broken you in two,” a student of literature who meets the girl he calls Flaca (skinny) in a class on James Joyce—and who is terrified that, without warning, his ghetto pass might be revoked.

In one of the loveliest passages in Dickens, Little Dorrit, en route from England to Italy, reflects on the strangeness of having gone from poverty to material comfort. In “The Cheater’s Guide to Love,” the final story in This Is How You Lose Her, Yunior—by now a writer who can travel to New Zealand to walk on the beach where The Piano was filmed—has also experienced a dramatic change in status. But as the title of the story and of the collection implies, the highs and lows that Yunior registers are not economic but erotic, and what he wants to talk about is what’s killing him: women. Regardless of how Yunior’s circumstances change, what remains constant is his inability to remain faithful to one woman. He fears that this flaw may be an inheritance from his father (“You had hoped the gene missed you, skipped a generation, but clearly you were kidding yourself”) or the result of being “a typical Dominican man.”

The book opens with Yunior vouching for his good character, as if to disarm the judgmental reader who may be dismayed by his propensity for falling in love and then treating his lovers badly:

I’m not a bad guy. I know how that sounds—defensive, unscrupulous—but it’s true. I’m like everybody else: weak, full of mistakes, but basically good. Magdalena disagrees though. She considers me a typical Dominican man: a sucio, an asshole. See, many months ago, when Magda was still my girl, when I didn’t have to be careful about almost anything, I cheated on her with his chick who had tons of eighties free-style hair. Didn’t tell Magda about it, either. You know how it is. A smelly bone like that, better off buried in the backyard of your life. Magda only found out because homegirl wrote her a fucking letter. And the letter had details. Shit you wouldn’t even tell your boys drunk.

Tenderhearted, vulnerable, funny Yunior is a good guy—a good guy with a problem. And if his problem becomes the reader’s problem, it’s not because we judge, and disapprove of, his weakness for the ladies. What’s troubling is that more than half the stories in the collection follow the same arc: Yunior cheats on the girlfriend he adores, then tries to keep his infidelity secret until he is found out, abandoned, and stricken with heartfelt grief and regret.

Which girlfriend was it who discovered the correspondence from fifty other women in his e-mail trash can? Which one did he try to convince that the incriminating section she’d read in his journal was just part of his novel? Inevitably, this sameness leaches into the language, which loses its jaunty, manic edge and starts to echo the dating and breakup stories that one can overhear on the subway and in the corner coffee shop:

When I returned to the bungalow that night, Magda was waiting up for me. Was packed, looked like she’d been bawling.

I’m going home tomorrow, she said.

I sat down next to her. Took her hand. This can work, I said. All we have to do is try.

The enthusiasm with which Yunior celebrates what he calls the pulchritude of each new love also begins to seem repetitive:

You, Yunior, have a girlfriend named Alma, who has a long tender horse neck and a big Dominican ass that seems to exist in a fourth dimension beyond jeans. An ass that could drag the moon out of orbit.

And we may feel that, even in the depths of his penitence and his efforts to reform (“You claim you’re a sex addict and start attending meetings. You blame your father. You blame your mother. You blame the patriarchy. You blame Santo Domingo. You find a therapist”), Yunior cannot resist striking a note of complaint and sexual boasting that is less than endearing. Poor Yunior! What’s a guy to do when so many beautiful women keep throwing themselves at him?

The new collection contains several fully imagined and touching stories. In “Invierno,” a tender account of the physical and emotional shock suffered by a Dominican family transplanted straight from the tropics to the inhospitable New Jersey winter, two young brothers learn English by watching Sesame Street and the news:

On the TV the newscasters were making small, flat noises at each other. They were repeating one word over and over. Later when I went to school I would learn that the word they were saying was Vietnam.

Funny, unsentimental, and surprising, “The Pura Principle” portrays the helplessness and the near psychosis that can alternately paralyze and inflame a household in which a beloved family member is dying. Even the limitless mess of maternal love (“My mother couldn’t resist my brother…. If he’d come home one day and said, Hey, Ma, I exterminated half the planet, I’m sure she would have defended his ass: Well, hijo, we were overpopulated”) is tested when Yunior’s desperately ill brother Rafa brings home a girl whose affection for him is transparently based on the hope that marriage will improve her immigration status:

My mother was super evil to Pura. If she wasn’t getting on her about the way she talked, the way she dressed, how she ate (with her mouth open), how she walked, about her campesina-ness, about her prieta-ness, Mami would pretend that she was invisible, would walk right through her, pushing her aside, ignoring her most basic questions. If she had to refer to Pura at all, it was to say something like Rafa, what would Puta like to eat? Even I was like Jesus, Ma, what the fuck.

In “Miss Lora,” sixteen-year-old Yunior, still mourning his brother, stumbles into a love affair with an older woman: a high-school teacher.

Miss Lora wasn’t nothing exciting…but what she was most famous for in the neighborhood were her muscles. Not that she had huge ones like you—chick was just wiry like a motherfucker, every single fiber standing out in outlandish definition. Bitch made Iggy Pop look chub, and every summer she caused a serious commotion at the pool.

Lit by the stark, incandescent flash of intimacy that can illuminate the brief romances that the young sometimes have with unlikely or inappropriate people, “Miss Lora” is reminiscent of Roberto Bolaño’s haunting “Gómez Palacio,” though with sex substituted for inchoate longing, and with harsh betrayal instead of the poetic, melancholy farewell that concludes the Bolaño story. With remarkable compression, Díaz depicts the enduring damage that had been inflicted by the secrecy, the compulsiveness, and the imbalance of Yunior’s relationship with Miss Lora:

It takes a long time to get over it. To get used to a life without a Secret. Even after it’s behind you and you’ve blocked her completely, you’re still afraid you’ll slip back to it. At Rutgers, where you’ve finally landed, you date like crazy and every time it doesn’t work out you’re convinced that you have trouble with girls your own age. Because of her.

If “Miss Lora” is more affecting and impressive to think about than to read, it’s because of the way it is written. Here, as well as in three other stories in the new collection and one (“How to Date a Browngirl, Blackgirl, Whitegirl, or Halfie”) in Drown, Díaz employs the second-person point of view and the present tense. (“It is the first time any girl ever wanted you. And so you sit with it. Let it roll around in the channels of your mind.”)

It’s not as if this technique has never been used effectively. But more often than not, it’s distracting: a device that calls attention to itself, like someone waving and doing jumping jacks in the background when a TV reporter is broadcasting from a crime scene. Though we understand that the “you” is not the reader but Yunior—the writer is speaking directly to his protagonist—it’s nonetheless unsettling and oddly implicating to be told that “you” are feeling or doing something. I am? We did?

Our disquiet grows when the weight of Yunior’s obsession flattens out his language, when a narrative begins to seem one-dimensional and thin, when we feel that Díaz has succumbed to the temptation to repeat himself, and when we find ourselves being told, yet again, about the painful and humbling aftermath of the latest of your—that is, Yunior’s—casual or serious affairs:

A month later the law student leaves you for one of her classmates, tells you that it was great but she has to start being realistic. Translation: I got to stop fucking with old dudes. Later you see her with said classmate on the Yard. He’s even lighter than you but still looks unquestionably black. He’s also like nine feet tall and put together like an anatomy primer. They are walking hand in hand and she looks so very happy that you try to find the space in your heart not to begrudge her.

The language (“like nine feet tall…she looks so very happy that you try to find the sp ace in your heart not to begrudge her”) is not merely straightforward but desiccated, exchanging the humor and vibrancy of Díaz’s best writing for the vocabulary and the counsel of pop psychology. “Try to find the space in your heart not to begrudge her.”

Even the least-inspired stories in This Is How You Lose Her won’t tempt Junot Díaz’s fans to give up on him, or on Yunior. But passages such as the one above do make us hope that Yunior will get over his latest heartbreak, and that Díaz will remember what he so ably demonstrated in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao: a wider, brighter, and more interesting world of other people—and of language—exists beyond the circle of hell reserved for serial cheaters suffering the torments of remorse and romantic obsession.