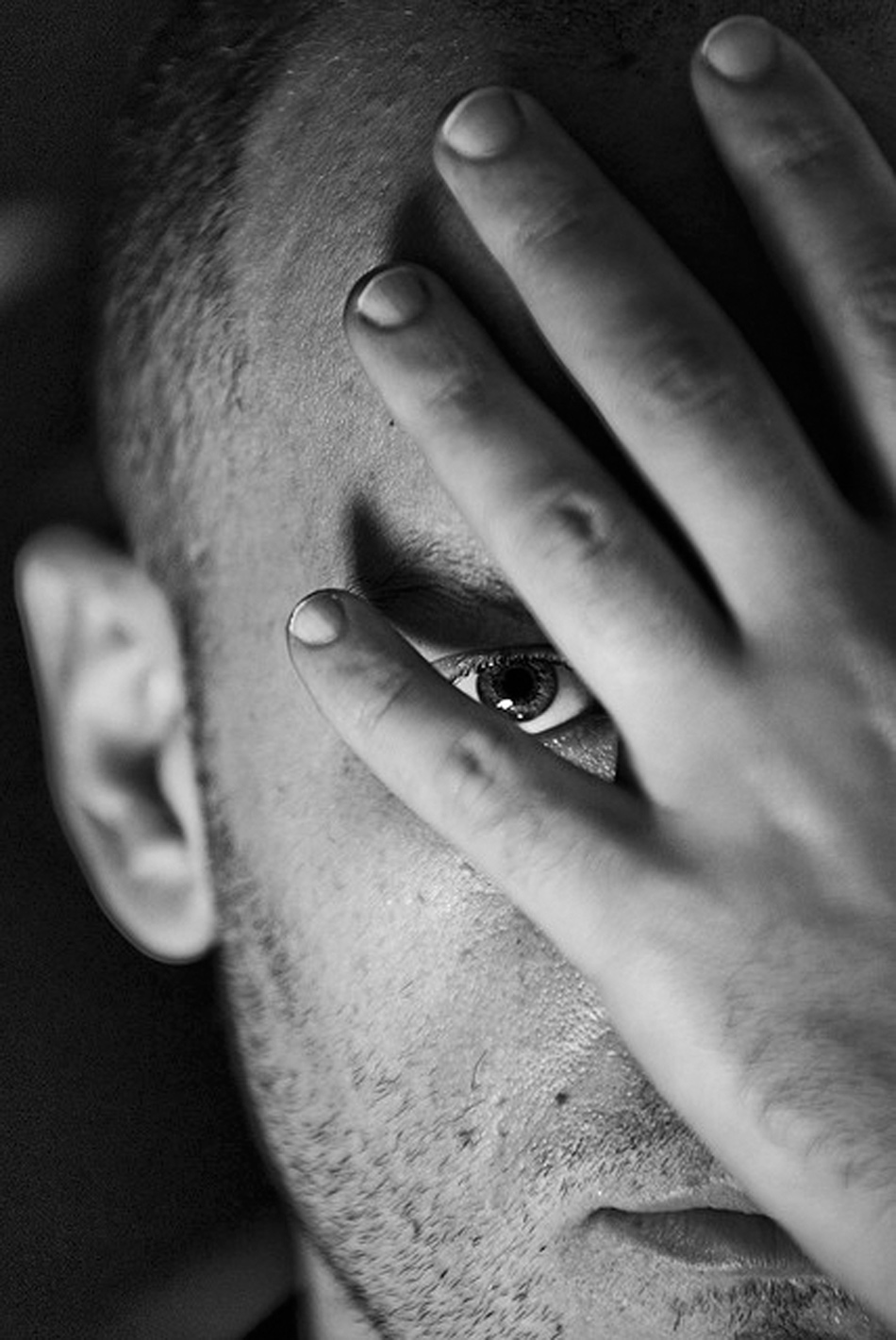

All normal people are normal in the same way; each mad person is mad in his own way.

—Freud’s Sister

Like the fine mist of poison gas that hisses into the Nazi death chamber at Terezín at the terrifying conclusion of Freud’s Sister, obliterating the carefully preserved memories that comprise the novel, an air of paralyzing melancholia pervades virtually each page of this meditative work of fiction by a Macedonian writer born in 1975, whose appropriation of the private life of Freud’s youngest sister Adolfina and of the Holocaust generally is bold and unexpected. This is Smilevski’s third novel, and since it is a joint portrait of Adolfina Freud and her oldest sibling Sigmund, it dares to provide a kind of shadow biography of Freud that is highly critical of the “great man,” seen from the perspective of an admiring sister whose life, like the lives of three other Freud sisters, Freud is charged with having neglected to save from the Nazi death camps.

Imagined biographies, like imagined histories, are works of fiction primarily, yet most readers expect, not unreasonably, that a “novel based in fact” (as Goce Smilevski describes Freud’s Sister) will explore probability rather than merely possibility. Smilevski makes his intentions clear in his Author’s Note:

Although Sigmund Freud wrote that “reality will always remain unknowable,” we do know about Freud’s exit visa [from Austria, 1938] and the opportunity it represented for his sisters, and about Freud’s final months spent in exile in London—they are documented in detail. We also know about the fate of Freud’s sisters. Their final months, however, are lost to history.

Freud referred to Adolfina in a letter as “the sweetest and best of my sisters”; from letters, Smilevski says, we know that Adolfina was “mistreated by her mother, that she lived with her parents as an adult and cared for them until their deaths,” and “that she spent her life in loneliness.”

The silence around Adolfina is so loud that I could write this novel in no other way than in her voice. The well-known facts of Sigmund Freud’s life were like scenery, or like the walls of a labyrinth in which I wandered for years, trying to find the corridors where I could hear Adolfina’s voice so I could write it down, and in this way rescue in fiction one of the many lives forgotten by history.

The challenge for the writer of fictitious history/biography is to create a “voice” that is both original and appropriate—in this case, the voice of a virtually unknown person who is used, by the author, as a kind of lens, at times a virtual rifle scope, with which to view Sigmund Freud in a way that is sure to be provocative.

In its most distilled form, Freud’s Sister is a dialogue between the imagined voice of the silenced Adolfina and the highly articulate voice of Sigmund Freud. It is in those touchingly rendered scenes in which Sigmund meets with his “sweetest and best” sister, spaced through the decades of their lives, that Freud’s Sister acquires a dramatic urgency otherwise missing from the intensely inward, frequently hallucinatory and surreal text of impressionistic reminiscences and philosophical musings of Adolfina and others imagined by the author.

When Sigmund is present, the novel comes into sharp focus: as if inspired by Sigmund’s intelligence, a far cooler and more detached intelligence than her own, Adolfina is capably of speaking clearly and persuasively. At other times Adolfina is scarcely articulate, and exasperatingly passive, to a degree that suggests mental retardation. Years pass in Adolfina’s life in which nothing seems to happen of any significance: apart from an early, disastrous love affair with a pathologically depressed younger man named Rainer Richter, Adolfina has no interests, no work, no training, no education, no life other than that of sister to the ever more famous and notorious Sigmund Freud and daughter to a malevolent and unmotherly mother.

Yet like a cruel fairy tale Freud’s Sister manages to suggest, even as Adolfina’s life becomes ever more narrow and helpless, that there might still—somehow—be a way for her to be “saved”; there is the desperation of hope in the face of doom, as in the pathetic reasoning of a fellow prisoner whom Adolfina encounters in the first Nazi camp:

This is not a true camp but a transit camp, a way station. Trains, each holding a thousand people, occasionally depart from here for the other camps. It is different there…. They say that people are sometimes brought into rooms where, they are told, they are going to shower…. Poisonous gas is then released, and they suffocate…. So it is best for us to remain here as long as possible. Until this evil subsides. Then we will all go home.

Freud’s Sister begins in the last year of Adolfina’s life, 1938, in Vienna. In a sequence of surpassingly painful vignettes the elderly woman “sifts through her earliest memories,” each of which involves her brother Sigmund, six years her senior: as a boy he stroked her cheek with an apple, he whispered to her an enigmatic and ominous fairy tale of a bird that tears out its own heart, and he gave her a knife. (Decades later, when both are old, and Sigmund is nearing his betrayal of Adolfina and her sisters, as he is nearing his own death by cancer, Sigmund denies ever having told Adolfina the fairy tale.)

Advertisement

Two of the Freud sisters—Paulina and Adolfina—are taken with others from the Jewish quarter to a park where they are forced to run as German soldiers aim rifles at their backs:

Hundreds of old legs set off running. We ran, we fell down, we stood up, we began running again, while behind us we heard the soldiers’ laughter, sweet with carelessness and sour with the enjoyment of someone else’s pain.

For the time being, the terrified sisters are allowed to live, and to return to their home in the Jewish quarter; the next day, Adolfina visits the eighty-two-year-old Sigmund, to appeal to him to acquire exit visas for his sisters, as he’d done for his own family. But Sigmund is curiously unmoved by Adolfina’s plea, saying repeatedly that the Nazi violence is not going to happen in Austria, though, as Adolfina has tried to tell him, it has already happened—to her and their sisters. With maddening indifference, as he fusses with his “ritual cleaning of the antiques in his study,” Sigmund insists that such harassment won’t last long in Austria; when Adolfina counters by saying that the occupation of Austria is the start of Hitler’s campaign to conquer the world and to “wipe anyone who is not of the Aryan race from the face of the earth,” Sigmund, in Slimenski’s rendering, says placidly that Hitler’s ambitions won’t be fulfilled:

In just a few days, France and Britain will force him to withdraw from Austria, and then he will be defeated in Germany as well. The Germans themselves will beat him; the support they are giving Hitler now is only a temporary eclipse of their reason…. Dark forces guide the Germans now, but somewhere inside them is smoldering that spirit on which I, too, was nurtured. The nation’s madness cannot last forever.

Adolfina’s older brother Sigmund has long been a defender of all things German, and with some disdain for the Jewish religion; for him, as for others in the Freud family who have wished to imagine themselves fully assimilated into German culture, German is the “sacred language.” Adolfina thinks of how, in this fierce identification with Germany,

the slender thread was broken between us and our forgotten ancestors. We were the first nonbelievers in the long line of generations from the time of Moses to our own…. We were enraptured with the German spirit and did everything to become a part of it.1

At this crucial meeting, Sigmund refuses to listen to Adolfina. He quotes from an article by Thomas Mann titled “Brother Hitler,” in which the “old analyst” who lives in Vienna is imagined as the (unarticulated, unconscious) reason for Hitler’s having invaded the city—“his true and authentic enemy—the philosopher and unmasker of neurosis, the great deflator, the very one who knows and pronounces on what ‘genius’ is.’” In Smilevski’s recapitulation, Sigmund’s pride in Mann’s words blinds him to the reality of Hitler’s invasion of Austria and what it will mean for the Jewish community and for his own family.

Following this meeting, Sigmund distances himself from Adolfina and sees her again only just before he flees to London. His reasons for leaving Vienna are blatantly hypocritical: “I am going not because I want to but simply because some of my friends, diplomats from Britain and France, have insisted that the local offices give me exit visas.” Failing to provide visas for his sisters, Sigmund will be taking with him his wife, their children, and their children’s families, as well as his wife’s sister Minna, two housekeepers, Sigmund’s personal doctor and his family, and “Jo-Fi,” Sigmund’s pet dog.

It’s the last that Adolfina will see her brother, who will die of cancer not long after relocating to London. Abandoned in Vienna, Adolfina and three of her sisters are eventually rounded up, with other Jews, and brought by freight car to a “small fortified town” where they live in a barracks. There, Adolfina is befriended by Ottla Kafka, whose brother Franz died in 1924; in a curious interlude, Ottla recites her brother’s little story “The Bachelor’s Misfortune” to Adolfina. It is Ottla who speaks of the “way station” as a place where no one will die, though very soon Ottla is sent by train to another camp where, in the company of young children, she is executed. As vividly as if it were her own death, Adolfina imagines the awful scene:

Advertisement

I thought of them being unloaded at the camp and led to a room where they’re ordered to strip off their clothes. I heard Ottla tell the children they must shower first, and advise each of them to pay attention to exactly where they were leaving their clothes, because after the shower they would need to get dressed as quickly as possible so they could get to the beach…. Some of them extend their arms, expecting jets of water. But then, instead of water from the showers, a poisonous gas spreads out from somewhere.

Following this scene, Freud’s Sister becomes an effort of reclamation, as the doomed Adolfina recalls her life in dreamlike detail. “At the beginning of my life there was pain”—this melancholy statement sets a tone from which there is virtually no variance through Adolfina’s childhood, girlhood, and adulthood. The author seems to have been considerably challenged in imagining a life for the “silenced” Adolfina apart from her relationship to her brother. Adolfina fails to achieve anything like a distinctive identity. Her mother persists in perceiving her youngest child as “the pain of her life” and says repeatedly to her, “It would have been better if I had not given birth to you.” (Adolfina’s mother had been forced into a loveless marriage with a much older man and had lived in poverty and misery.)

Adolfina interprets her mother’s seeming hatred of her as a kind of perverse love, or as denied and repressed love—“She loved me to the point of forgetting her unhappiness.” Until Adolfina’s mother becomes elderly and dependent upon her youngest daughter to take care of her, this “Mama” is so one-dimensional a figure, so pathologically negative, that the reader becomes impatient with her and with the maddeningly passive Adolfina who seems incapable of defending herself, unable to leave her claustrophobic home life. Especially, it’s difficult to reconcile the affectless Adolfina with the highly articulate and contentious young woman who engages her brother in spirited discussions on such subjects as Freud’s theory of “penis envy” in the female and the “infantile” belief in immortality; apart from these encounters, Adolfina remains a blurred figure, a fate rather than an individual.

Similarly, Adolfina’s relationship with her (perpetually depressed) soul mate and lover Rainer Richter ends in abject humiliation and unhappiness. Initially drawn to each other as lonely children—“There was something of that union of shadows, that touch of reflections, that weaving of two intangibilities, in those moments when Rainer and I were together”—their fragile love can’t bear the strain of Rainer’s obsessive despair and egotism. Treated cruelly by Rainer, Adolfina is ever forgiving, and compliant; she becomes pregnant, but insists upon an abortion after Rainer’s suicide, though the loss of this shadow child will haunt her for the remainder of her life. Rainer’s debased prostitute mother had given him away to be adopted by a bourgeois family, whom he takes for granted:

Yet that idyllic existence [with his adoptive parents] did not lessen Rainer’s sorrow. The child remained immersed in his pain, as if sunk in water…. No one knew where his melancholy came from, or what provoked his sighs or turned his gaze aside.

Not even a brief appearance by the iconoclastic artist Gustav Klimt can break the novel’s spell of unrelieved gloom. Nothing of this brazenly gifted artist’s ultra-decorative eroticism and aesthetic audacity makes its way into these somber pages. It strains credibility that Adolfina never sees one of his pictures, and seems to have no interest in doing so. Through her narrow eyes, Klimt is a shadowy figure like the others, a caricature of a sexist male in his obsessive vulgarity: Klimt “was talking about shameful things that were kept hush in every home and among all but the very dregs of society.” (It is noted, however, that Klimt begets fourteen children with numerous women who model for him—all male, all “Gustavs”—and remains supremely indifferent to them.)

Adolfina is befriended by Klimt’s older sister Klara, an exponent of women’s rights, and one of the few characters of distinction in Freud’s Sister. That the courageous Klara suffers a mental breakdown and voluntarily institutionalizes herself in a Viennese psychiatric hospital (“the Nest”) is ironic, yet unsurprising given the rigidity and repression of Austrian society at this time. Adolfina observes:

We were the first generation of girls born after the introduction of the word sexuality, in 1859; we were girls at the time when some called intimate relations between male and female bodies “bodily acts,” others “venereal acts,” yet others “instincts for procreation.” From this union of two bodies one expected the elevation of souls to some heavenly sphere, but it was also regarded as an animal act that sullied the soul…. That was our era, a time of silence concerning carnality.

Adolfina follows Klara into the Nest, where she remains for seven years as a mental patient under the direction of a psychiatrist named Dr. Goethe, who resists calling his hospital a “psychiatric clinic”—he prefers the cruder term “madhouse.” Like Sigmund Freud, Dr. Goethe exudes an air of absolute confidence in his theories; he seems to welcome exchanges with his more articulate patients, and he engages in a lively debate with Sigmund Freud on the nature of treating madness (“A greater revolution for humanity than the theories of Copernicus, Darwin, and Freud put together came with the invention of the toilet bowl…in 1863”), but he never changes his mind.

Much of the middle section of Freud’s Sister takes place in the Nest, a sort of novella-within-a-novel exploring the proposition that “all normal people are normal in the same way; each mad person is mad in his own way.” Here we meet a number of psychiatric patients with whom Adolfina interacts. There is running commentary on the phenomenon of madness—how long it took for “madness” to be dissociated with demonic possession and acknowledged as illness—and there are impressionistic prose-poems on the subject (“Madness is an oar that strikes the wall instead of water, and it strikes the wall, and strikes, and strikes, and strikes…”).

There is an occasional visit by Sigmund to Adolfina, introducing an element of urgency and drama into the hypnotic stasis of the Nest in which time seems to stand still as in an enchantment. Astonishingly then, and inexplicably, Adolfina simply walks out one day and returns to her home—not unlike Hans Castorp of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, who’d confined himself in a tuberculosis sanitarium for seven years. It’s as if Adolfina has never been seriously ill, and this middle section of Freud’s Sister is a way of biding time until the final chapters, set in the early 1940s, when Adolfina and her sisters are taken away to the Nazi camps and the novel comes to its stunning close.

The most engaging passages in Freud’s Sister, the exchanges between Adolfina and Sigmund, are spaced through the novel at intervals, with the most passionate in the penultimate chapter, set unexpectedly in Venice. As a young woman Adolfina had yearned to visit Venice with her lover Rainer but had never had the opportunity. Now, though Sigmund has brought her to the fabled city with him and his youngest daughter Anna,2 Adolfina, so long passively mired in melancholia, perversely refuses to look at the city but walks with her head bowed. Adolfina’s last recorded memory is of an intense conversation with Sigmund about religion and “immortality,” held in front of a Bellini painting of the Madonna and child. In this exchange, in which sister and brother appear to be speaking about much more than mere ideas, Sigmund is scornful of the very concept of “immortality,” while Adolfina accuses him of unconsciously imagining himself “immortal”:

You do not have fear [of dying]. You express your ideas about the nonexistence of immortality with such indifference, as if you were convinced of your immortality…. There is something in your voice that says, Yes, immortality does not exist, everyone is mortal, except for me.

Sigmund dismisses Adolfina’s hope that there is, somewhere, an “eternal present” as an “infantile conjecture.” Adolfina speaks at length, with an idealism we haven’t seen in her before and are not certain how to interpret:

In cosmic time, everything is meaningless, because in it, everything will end and lose its meaning. But in eternity everything that ended in cosmic time will once again achieve its meaning, a meaning not given to us to understand and experience while we are in our time.

It may be that Adolfina’s words are meant to provide an idealized meaning to Freud’s Sister to counter the novel’s unremitting despair, but this outburst is hardly convincing. One is more likely to acquiesce in Sigmund’s observation:

Those who torment themselves most with these questions concerning the meaning of life are those who, in their yearning for happiness, have succeeded least in attaining it.

Reading Freud’s Sister is not an easy or pleasurable experience. That Freud could have saved his four elderly sisters from the Holocaust if he’d only made the effort is the novel’s raison d’être, according to the author’s commentary; yet is this true? Or were the circumstances more complicated than Smilevski wishes to acknowledge? Freud managed to bring with him to London a retinue of people including his personal doctor and his doctor’s family, as well as his pet dog; but it was through the ministrations of Ernest Jones, president of the International Psychoanalytic Association, that immigration permits were acquired for these parties, to allow them to live in England.

Others in Freud’s extended family also managed to flee. (Some sources suggest that considerable payments were made to Austrian authorities, to facilitate these permits.) Adolfina’s account of the “betrayal” is necessarily one-sided and uninformed—she knows only what Sigmund chooses to tell her, which is misleading, and minimal. Of course Freud’s Sister is a work of fiction, and should not be held to account as “inauthentic.” Yet the reader feels some lingering unease, and this aspect of Freud’s Sister is sure to provoke controversy.

Though the novel is fairly short, it often seems interminable, especially in the episodic interior section set in the Nest. Knowing the novel’s end—we are aware in every line of Adolfina’s imminent fate, as Adolfina herself anticipates it—makes for an airless narrative, and allows us to appreciate how a work of art requires expansion, a sense (however it may turn out to be illusory) of freedom. The sense of fatedness and leaden resignation characteristic of Grimms’ fairy tales can’t be sustained in prose fiction for more than a few pages. Despite the brilliant exception of certain works of Samuel Beckett that make of the nihilistic vision something eloquent and even witty, it is very difficult to infuse a work of such deathly inertia with anything like a transcendent meaning.

Though Freud’s Sister is very different in tone, subject matter, and intention from the sinister German film The White Ribbon (2009) by Michael Haneke, the musical Spring Awakening (2006) by Steven Sater, and the Holocaust novels of Aharon Appelfeld (notably Tzili, a parable-like 1983 tale of a dull-witted Jewish girl who survives the Holocaust almost inadvertently), Smilevsky’s novel obliquely resembles these works in its preoccupation with the explosive consequences of sexual and political repression in Northern Europe and with a nightmarish sense of the arbitrary nature of individual destiny. It is an exquisitely painful work of fiction in which the most terrible truths are contemplated with a catatonic sort of obliviousness: in the gas chamber at Terezín, Adolfina experiences the solace of forgetting:

I was entering into death and I promised myself that death is nothing other than forgetting • I was entering into death and I told myself that a human being is nothing except remembrance • I was entering into death and I repeated that death is forgetting and nothing else….

I will forget that I was born

I repeated this while I waited for my death • I repeated that death is only forgetting and I repeated what I will forget

I will forget

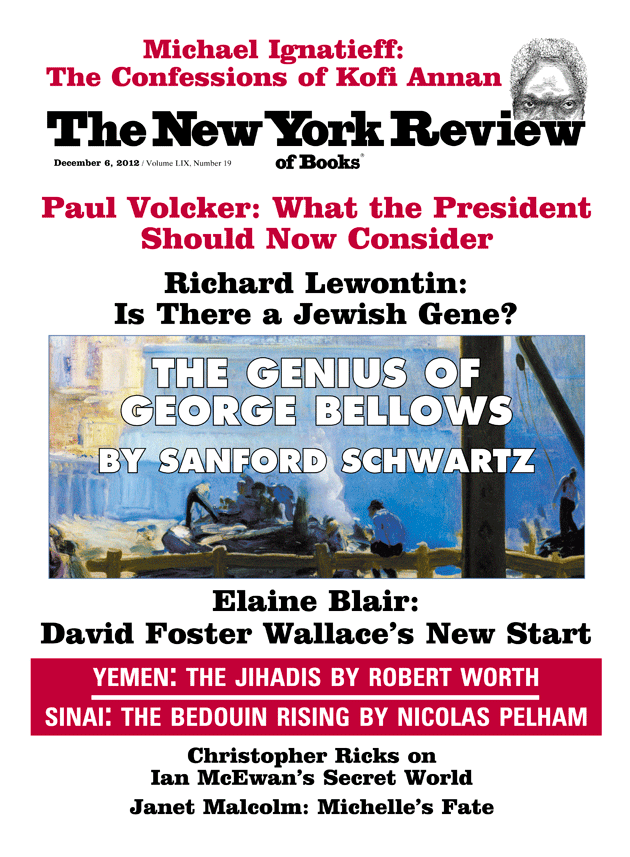

This Issue

December 6, 2012

-

1

In an extended analysis of Freud’s controversial monograph Moses and Monotheism (1937), Smilevski suggests that the purpose of Freud’s radical argument—to declare that Moses wasn’t a Jew and in this way “deny a people the man whom it praises as the greatest of his sons”—was to establish Freud himself as a “self-made leader and prophet.” Through the persona of Adolfina, Smilevski deconstructs Freud’s motives:

Throughout his life [Freud] tried to prove in his works that the essence of the human race is guilt: everyone was guilty because everyone was once a child, and in the competition for its mother’s love, every child desires the death of its adversary, its father…. He blamed the most innocent; the most innocent and the most helpless carried this primordial sin.

In his self-mythologizing, Smilevski writes, Freud imagines himself as Cain, and as Noah, as well as Oedipus; but in those desires he doesn’t wish to acknowledge he also wanted to be a prophet—“and so he took Moses away from the Jews.” Freud “wanted to be unique, autonomous, self-made,” as he wanted “to lead the human race to freedom from the I, to free humans from the fetters of repression and the dark abysses of the unconscious.” His identification with German culture is predominant, and his sense of himself as Jewish secondary:

“My language is German. My culture, my achievements are German. I considered myself intellectually to be a German, until I noticed the growth of anti-Semitic prejudices in Germany and in German Austria. Since then, I prefer to call myself a Jew.” He said it just like that: “I prefer to call myself a Jew,” and not “I am a Jew.”

Adolfina concludes that her brother associates his “Jewishness” with his “blood”—“the thing he could not change, and he felt a kind of shame toward it.”

For differing views of the subject of Freud’s Jewishness see David Bakan, Sigmund Freud and the Jewish Mystical Tradition (Van Nostrand, 1958); Peter Gray, A Godless Jew: Freud, Atheism, and the Making of Psychoanalysis (Yale University Press, 1987), and William J. McGrath, “How Jewish was Freud?” The New York Review, December 5, 1991. ↩ -

2

In Smilevski’s portrayal of the father-daughter relationship, Freud’s daughter Anna, deprived by him of the medical school education she’d wanted since Freud “did not believe that studies were for girls,” doesn’t sink into depression like her aunt Adolfina but seems instead to have passionately devoted herself to her father, as if in denial of what might have been her justified resentment of him. Smilevski’s assessment of the great man’s seeming exploitation of his daughter is presented as a shrewd observation of Adolfina’s: Anna

hated all the women who were close to him. She hated his sisters…. From her earliest youth, she was determined to devote her life to him; her daily routine consisted of the arrangement of what Dr. Freud had written, in consultation about his patients, the organization of his professional travel, assisting in the management of his illnesses. Sometimes she related to him as a daughter, sometimes as a spouse, sometimes as a child, most often as a scholar. But behind her cheerfulness and chattiness, behind her grand idea to serve her great father, one sensed a kind of mute emptiness.

As much a victim of patriarchal repression and sexism as Adolfina, no less mute and empty than Adolfina, Smilevski’s Anna yet has an advantage unavailable to her aunt: “I imagined that, after [Sigmund’s] death, concern for his works would give meaning to her life.” What has eluded Adolfina through her embattled lifetime is precisely this—meaning.

Smilevski’s portrait of Anna Freud (1895–1982) is devastatingly reductive: one would not guess that the historic Anna Freud not only continued her father’s work but established the field of child psychology and child psychoanalysis, nor that she was the author of several books on the psychology of children in wartime and established the Hampstead Child Therapy Course and Clinic in London, where she’d fled with her father in 1938 after having been interrogated by the Gestapo. ↩