1.

Leonard Cohen’s songs mix the sleazy and the sacred in ways that break down both categories. This music, delivered in Cohen’s nasal non-voice, often played on cheap synthesizers, shoddily produced, sometimes badly recorded and unreliably distributed, nevertheless finds unlikely access to words like “holy,” “saint,” and “prayer” as though to transcend its origins in the gut and the loins. Cohen has attracted many disciples and inspired many conversions. He is one of the most beloved figures in modern pop, but everyone who listens to Cohen feels he has bailed him out of impending obscurity.

He is a kind of permanent alternative to whatever it is you’ve been listening to: I came to him after I’d listened too much to the Nineties West Coast band Pavement, with whom he has zero in common. Somehow I felt I’d been making a mistake, all this time, listening to other bands and singers. The feeling passed, but it’s a common one: Cohen inspires not just loyalty but a weird monogamy.

Cohen has the ubiquity of Waldo or Zelig, turning up on the fringe of every picture. People who have never even heard of Cohen have heard his songs. He is a regular on movie soundtracks of all kinds. His songs created much of the power of Robert Altman’s marvelous Seventies western, McCabe & Mrs. Miller. In another vein, “Hallelujah,” his most famous song, played at the end of Shrek as the two computer-generated ogres embraced. This was an odd choice, considering the fact that the most famous lyrics from that song are “remember when I moved in you/the holy dove was moving too”: I don’t need to picture Shrek and his girl in that kind of detail. Cohen is a figure out of the movies—more Altman than Shrek—and his songs, which create the ambience they describe, are essentially cinematic. When you see him on stage, his soulful mien framed by a trilby and a tie, Cohen does more than perform his songs: he stars in them.

He has had a nomadic life, moving from Montreal to New York to London and Greece to Mumbai and Singapore and back again. He is not identified with any one place or scene. He hung with Andy Warhol and Judy Collins in the same day. His music is the work of a man constantly entering new milieus, making the new appeal. His lyrics are a species of banter or rapport, unlike, say, Dylan’s, which exist in a hermetically fused chamber of their own brilliance when they do not practice outright exclusion or even accusation. This ambivalence, approaching disdain, for his audience is Dylan’s genius; Cohen, who was called “the Canadian Bob Dylan” when he appeared on the scene in the mid-Sixties, could not be more different. Cohen’s music assumes admiration from his listeners and assumes, furthermore, that admiration is just uncatalyzed lust. Many people who have heard Cohen’s music, over the years, have right away gone to bed with him—or, if he was unavailable, with the person next to them. He is one of those sublime charlatans who can make spiritual matters seem to depend on taking immediate carnal action.

He is a throwback: a poet (Bono, who nobody ever thought of as a poet, said he was our Shelley, while others name Rimbaud and Baudelaire); a man, Cohen has said, “born in a suit,” a figure out of old Montreal and the nearby minor-league borscht belt of the Eastern Townships and the Laurentians. The Cohens were prominent in Montreal, but the family was in some disarray: Cohen’s father died when Leonard was nine; his mother remarried. As a teenager Cohen often came down from his perch on Westmount, where the Anglos and wealthier Jews lived, to walk the streets of the seedier districts and “catalogue the magic and tricks, rubber cockroaches and handshake buzzers,” as Cohen wrote, and to meet the “men who wore overcoats even in summer.”

Joni Mitchell, who met Cohen in Greenwich Village in the Sixties and fell for him instantly, has a gorgeous song about sleeping on Cohen’s mother’s bed in Montreal while Cohen, ever the observer, watches her sleep:

It was a rainy night

We took a taxi to your mother’s home

She went to Florida and left you

With your father’s gun, alone

Upon her small white bed

I fell into a dream

You sat up all the night and watched me

To see, who in the world I might be

“Rainy Night House” along with two other of Mitchell’s songs—“A Case of You” and “That Song About the Midway”—forms one of the most inspired and beautiful groups of songs by one great singer about another in the history of pop. In “Rainy Night House,” Mitchell describes Cohen as “a holy man/on the FM radio”; many years later she decided he was merely a “boudoir poet,” though her own song shows how unusual an experience it was to pay a visit to the boudoir with Leonard Cohen.

Advertisement

I’m Your Man is Sylvie Simmons’s new biography of Cohen, whom she calls “Leonard” throughout: she interviewed her subject extensively for this book, which sometimes is just a conduit for his million-watt charm. Anybody choosing to write an authorized biography of Cohen while he’s still very much alive has already submitted to his magnetism, if not the actual mesmerism Simmons describes in the early pages of the book. Cohen, in his early teens, has gotten his hands on a guide to hypnosis:

Finding instant success with domestic animals, he moved on to the domestic staff, recruiting as his first human subject the family maid. At his direction, the young woman sat on the chesterfield sofa. Leonard drew a chair alongside and…told her in a slow gentle voice to relax her muscles and look into his eyes…. Leonard instructed the maid to undress.

Do we believe all this? Hypnotizing domestic animals? Undressing the maid? I’m not certain I do, but if I did, I would not have Simmons’s response:

What a moment it must have been for the adolescent Leonard. The successful fusion of arcane wisdom and sexual longing. To sit beside a naked woman, in his own home, convinced that he made this happen, simply by talent, study, mastery of an art and imposition of his will.

The whole creepy story feels like a scene from a silent film starring Louise Brooks. But Simmons’s book is symptomatic of Cohen’s icky appeal—especially, as here, when it attempts to strike an analytic note. Whatever he did or did not do to those domestic animals and to his “domestic staff,” Cohen has made a career of figuring out how to do the kind of thing women couldn’t resist even if they tried.

2.

When pop stars are called “poets” it doesn’t always mean their lyrics are good enough to hold up on the page. Often it means simply that they have something of the bardic or shamanic in their swagger: this is why Jim Morrison was once called a poet but Paul Simon normally is not. But Cohen is, or at least was, indisputably, a poet. He published his first book while a student at McGill, long before he ever recorded a song.*

At McGill he fell in with Irving Layton, probably the best-known and most celebrated Canadian poet of the era. He and Layton caroused and drank and talked about women and studied poems by Wallace Stevens together; Cohen, twenty years Layton’s junior, was his apprentice, though others saw the two men as equals. Layton was part vascular and part oracular: his training included, Layton later remarked, opening to Cohen “the doors to sexual expression, to freedom of expression.” In return, Cohen has said, he taught Layton, always a shambles, how to dress.

This would have been about 1955. When you think about what the other great performers of Cohen’s generation were doing in 1955, the oddness of Cohen’s literary apprenticeship comes to seem definitive of his career. He was not scrounging blues records in North London or raiding the folk shops in the Village: he was breathing the air of Great Poetry with a man who considered himself to be the greatest poet and who considered Cohen to be next in the line of Canadian bards.

There is something uncommonly dynastic in Cohen’s early ascent, as though, in losing a father, he sought his lineage where fatherless kids often go, in literature. Music sprawls in all directions: Cohen heard it at his socialist summer camps, in jukeboxes, on the radio. But poetry is often a kind of peerage, and in the Fifties in Montreal it was handed from man to man. Cohen has always taken pains to depict his masculinity by outmoded means: the hat, the tie, the chivalry, and most of all the poetry.

Cohen published six books—four volumes of poems and two novels—between 1956 and 1966. When he landed again in New York in 1967, he was picked out of a crowd at Max’s Kansas City by Lou Reed of the Velvet Underground and introduced to Warhol and his circle. He was known as a writer in a crowd of musicians and artists. The connections are amazing to imagine. Nico, who had acted in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and dated both Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan, was now Warhol’s house “chanteuse” and was seeing Jackson Browne, at the time an obscure twenty-year-old guitarist whose song, “These Days,” Nico recorded on Chelsea Girls. Browne describes seeing Cohen, who had become well known after Judy Collins had a hit with his song “Suzanne,” seated in the front row at Nico’s shows “writing and looking at her.”

Advertisement

It is a good thing that Cohen ended up, a year or two later, taking the stage. His poems are not extraordinary. They do have a stoned gallantry and a gaudiness that lasts, but they are full of the kinds of large gestures that pass for wisdom at closing time, often lightly ironized. Here is “The Music Crept by Us,” written in the early 1960s, in its entirety:

I would like to remind

the management

that the drinks are watered

and the hat-check girl

has syphilis

and the band is composed

of former SS monsters

However since it is

New Year’s Eve

and I have lip cancer

I will place my

paper hat on my

concussion and dance

“Concussion” is the stroke of genius here, the authentic surprise in a poem otherwise full of stock remarks. Someone, perhaps Layton, must have convinced Cohen that poetry involved extremely inflated claims and blowsy affirmations. Here is a passage from “For E.J.P.” (“E.J.P.” is E.J. Pratt, the distinguished Canadian poet of the Thirties and Forties):

I chose a lonely country

broke from love

scorned the fraternity of war

I polished my tongue against

the pumice moon

floated my soul in cherry wine

a perfumed barge for Lords of Memory

3.

“For E.J.P.” was published in 1964, in Cohen’s blasphemously titled book Flowers for Hitler. It is hard to believe that only a few years later, Cohen performed for the producer John Hammond while sitting on the edge of the bed in his room at the Chelsea Hotel. The twelve tunes collected on The Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967) possess in spades the quantum of genius so sparely meted out in his poems.

As with all great songwriters, you see what is precisely special about Cohen’s art by noting how much is lost when it hits the page. This is why lyricists are not, however brilliant they may be, “poets”: Why should they be? Poetry lost the benefit of musical accompaniment aeons ago: it returns only very rarely and, when it appears, it takes a lot of getting used to. A kind of truce was struck: poets get the page and all the mental spaciousness that attends silent reading. Singers get to keep many of the devices of poetry—rhyme, imagery, and so on—plus the verbal work that song will not survive on the page.

But of all the lyricists people call “poets,” Cohen comes closest to surviving that hard passage into print. “Suzanne” is not a poem: too much depends upon the glorious, tentative melody backed by a choir of voices and strings. But you can see, even on the page, that Cohen’s sense of song includes the kind of inscrutable swerves of mind that great poets make. Somehow Constant Comment tea served to him by his friend’s gorgeous wife becomes “tea and oranges/that come all the way from China.” Cohen might have been thinking of Stevens’s “Sunday Morning” and its “late coffee and oranges/in a sunny chair”; in both cases, a secular Eucharist conjures the presence of Christ. Here is the second verse of “Suzanne”:

And Jesus was a sailor

when he walked upon the water

and he spent a long time watching

from his lonely wooden tower

and when he knew for certain

only drowning men could see him

he said All men will be sailors then

until the sea shall free them

The weak stress on the last syllable of every line ensures that we roll right into the next line in expectation of the strong stress: this is a literary effect, not strictly a melodic one, though the melody shapes it. And the way the song leaps across lines, looking for its next strong stress, suggests the song’s beautiful sense of how spontaneity and risk find a home within pattern and routine. It is a song about the surprise of ceremony.

Suzanne Verdal is not the only muse of Cohen’s to achieve fame: Marianne Jensen, of “So Long, Marianne,” has an entire Norwegian book written about her. But Suzanne has an additional claim to fame: she is one of the few women Cohen ever wrote about who refused to sleep with him. This might have been the source of the song’s mystery; women who are more forthcoming end up in a different sort of song. “Chelsea Hotel #2” is Cohen’s best song, though for important reasons he is not its best singer: that honor would go to Rufus Wainwright, whose operatic interpretations of Cohen’s melodies bring many of his songs the lives they wanted all along. Wainwright is gay, which changes everything about the force of its opening verses:

I remember you well in the Chelsea Hotel,

You were talking so brave and so sweet;

Giving me head on the unmade bed

While the limousines wait in the street.

The “you” in this song is Janis Joplin: their stories diverge a little, but according to Cohen, the episode in question unfolded because Joplin couldn’t find the guy she was looking for, Kris Kristofferson. The atmosphere of the song is utterly funereal (the unmade bed, the limousines “waiting” like hearses to take Joplin away), an effect driven home by a steady 3/4 beat, part dirge, part prom dance. Nothing in the print version approximates that beat.

Paradoxes abound when you think about the lyrical strength of Cohen’s best songs. They tend to be rather lushly orchestrated where we expect a spare presentation of voice. Other singers—Wainwright, the late Jeff Buckley, Jennifer Warnes—made his songs famous; often when people hear him singing them, their initial response is resistance. He claims to feel little sense of ownership; he has been negligent of copyright and other business matters, once losing all his money to a rogue manager while he, Cohen, was immersed in Zen meditation. “Hallelujah,” which has been recorded over two hundred times, is, for some, a nearly supernatural song, a song they feel brings them health and luck and bounty.

Cohen’s signature on his own songs is often faint, which makes others often better performers for them, even though the sensibility they convey is uniquely his. But since there are comparatively few songs (twelve albums in nearly fifty years) and they are so much alike (Cohen never had a country phase, or a reggae phase, or converted to evangelism), you can talk about a “Leonard Cohen song” the way you could never describe a prototypical Dylan song.

From the moment Judy Collins recorded “Suzanne,” his career has been in others’ hands; he occasionally shows up in it and sings his songs, but his nature is to wander in and out of his own work rather distractedly. He is now seventy-eight and recently released a new album and started a tour. His outfit hasn’t changed, but now the black hat and suit seem like mourner’s attire. In “Going Home,” the remarkable opening track on his new record, Old Ideas, Cohen, who often speaks in the role of someone talking about him, plays God:

I love to speak with Leonard

He’s a sportsman and a shepherd

He’s a lazy bastard

Living in a suit

But he does say what I tell him

Even though it isn’t welcome

He just doesn’t have the freedom

To refuse

In the Sixties, with his briefcase and his blazers, he seemed old and a square: he was thirty-two by the time he became popular with the people who distrusted anyone over thirty. Now that he has hit the road again, he seems preternaturally young: a musician working gigs, not, like so many of his contemporaries, a spectacle attracting endorsements. He isn’t going home, because really, he never left.

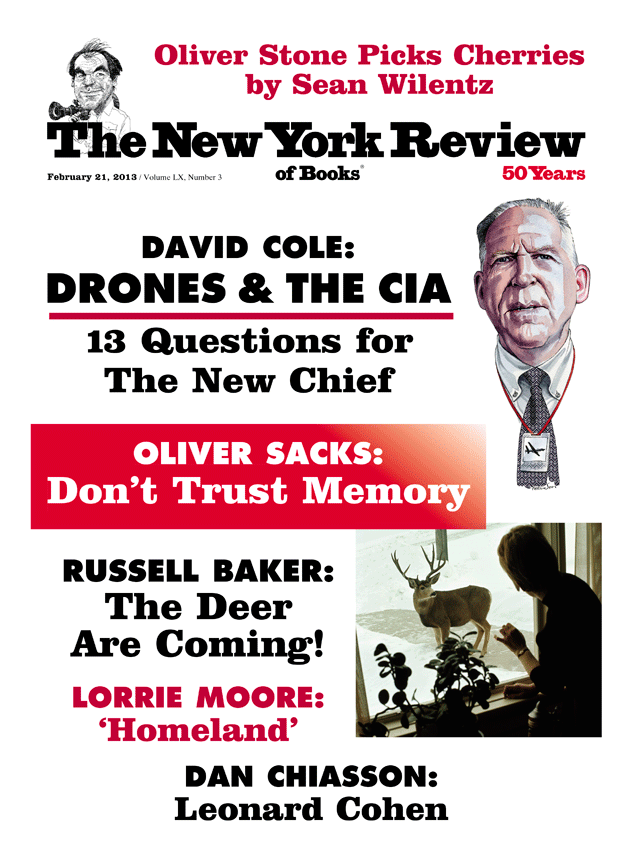

This Issue

February 21, 2013

Speak, Memory

13 Questions for John O. Brennan

Double Agents in Love

-

*

Let Us Compare Mythologies (McGill Poetry Series, 1956; reissued by Ecco, 2007). ↩