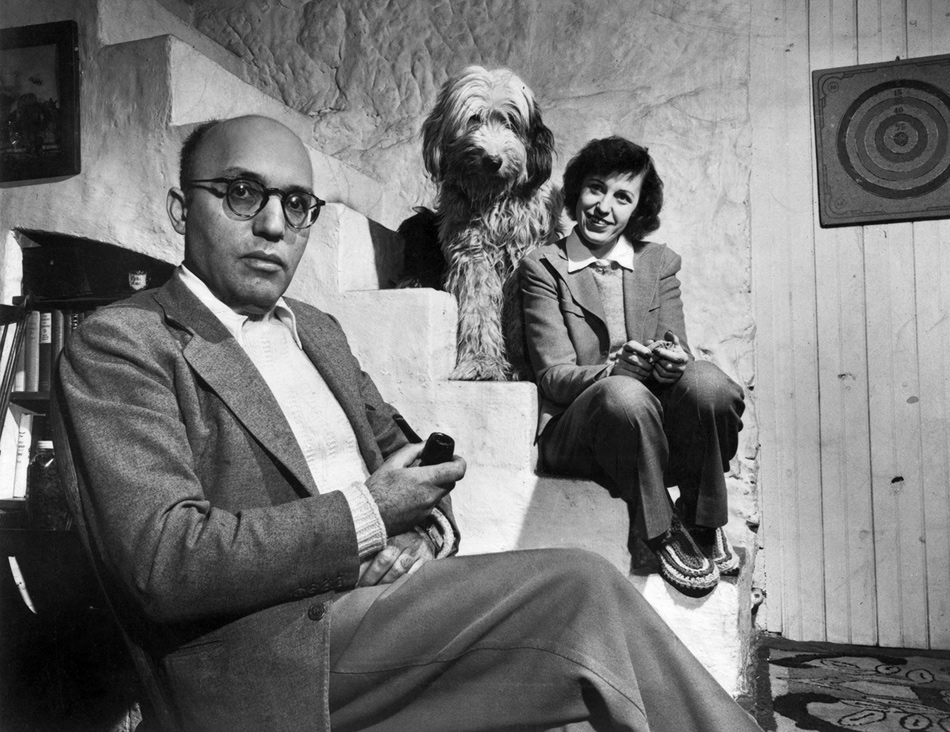

Love Song: The Lives of Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya is the title Ethan Mordden gives to his new work on these two major twentieth-century musical artists. But the relationship between Weill and Lenya was less a feverish romance than a very practical partnership, not so much a tender love song as one of Weill’s bereft Benares ballads. This is not to suggest that the couple’s feelings for each other were lacking in affection. Their marriage was fostered by deep personal connections and mutual tastes. But Lenya, who enjoyed a brief career as a teenage prostitute, was compulsively unfaithful to Weill throughout their lives together, both with men and with women. She also divorced Weill once for a tenor, later remarried him, and then, after his death, married two more men, both of them gay.

Lenya’s German biographer, Jens Rosteck, considers most of her erotic adventures to have been rehearsals for her career as a performer. From Mordden’s account of it, their relations could be described as a friendly affiliation between two Germanic professionals, Lenya from an Austrian working-class family, Weill from middle-class German Jews, one a cabaret artist, the other a serious composer, whose careers were mutually supportive, and who shared the same language, values, tastes, friendships, and musical projects, if not always the same bed.

Of the two, Kurt Weill may have been the more gifted, but Lotte Lenya was unquestionably the more dynamic. Weill seems to have had a rather retiring nature, while Lenya rarely held her tongue. Indeed, this relationship struck me as reflecting the kind one often finds between composers and lyricists, in which the style and content of a song is usually determined by the wordsmith (or in Lenya’s case the performer), even though it is the songwriter who usually provides its emotional imprint.

A classic example of this kind of partnership is the way the musical personality of Richard Rodgers was transformed after the death of his first Broadway collaborator. As the creative partner of the gay sophisticate Lorenz Hart, Rodgers wrote music vibrating with urban electricity—highly witty, often cynical, sometimes erotic—whereas, collaborating with the exurbanite Bucks County landholder Oscar Hammerstein II, his music became considerably more sunny, wholesome, rustic, and chaste. With Hart, Rodgers wrote “The Lady Is a Tramp,” with Hammerstein, “My Girl Back Home”; with Hart, “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered,” with Hammerstein, “How Do You Solve a Problem Like Maria”; with Hart, “Ship Without a Sail,” with Hammerstein, “Surrey with the Fringe on Top”; with Hart, “Manhattan,” with Hammerstein, “Oklahoma!”

There are, of course, a number of songwriters who managed to sustain their own style, whatever the contribution of the lyricist—Cole Porter, Frank Loesser, and Stephen Sondheim are a few examples. But these are composers who usually supplied their own lyrics, or (in Loesser’s case) lyricists who later provided their own music. Typically, Broadway musicals are composed by chameleons like Jerome Kern who would change color for virtually any lyric writer—P.G. Wodehouse (“Bill”), Oscar Hammerstein II (“Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man”), Dorothy Fields (“The Way You Look Tonight”), Johnny Mercer (“I’m Old-Fashioned”), and Ira Gershwin (“Long Ago and Far Away”), with songs so varied you were at a loss to identify a single source.

As for Irving Berlin, who also wrote his own lyrics, he not only adapted his style, he reshaped his whole temperament, assuming a new idiom, identity, and set of holidays after his expatriation from Europe. Over the ninety years that he wrote songs (he died at 101), this Russian-born Jew morphed into an American patriot (“God Bless America,” “This Is the Army, Mr. Jones”), a Wild Westerner (Annie Get Your Gun), and a celebrant of Christian holy days (“White Christmas,” “Easter Parade”). I mention this not to criticize but to dramatize the flexible nature of composers, as we know from the differences between Mozart’s work with da Ponte’s three librettos and his composing for Schikaneder’s singspiel, The Magic Flute.

Like all such generalizations, this one is open to exceptions (the most obvious ones being George Gershwin, whose unique rhythms dominated his brother Ira’s lyrics, and Leonard Bernstein, whose brassy syncopations were always unmistakable, whomever his collaborator). I suggest it to help us to understand why Kurt Weill changed course so radically after he and Lotte Lenya left Europe, a step ahead of the Nazis, to transplant themselves in American soil. As Mordden, a competent if somewhat hectoring student of German culture, writes, Weill’s major European influences were essentially the avant-garde classical composers Arnold Schoenberg and Ferruccio Busoni, under whose dissonant shadows he wrote his two symphonies, and the politically radical dramatists Georg Kaiser and Bertolt Brecht, who dictated his theater style.

Advertisement

It was Brecht, of course, with whom we are most likely to associate Weill. He certainly had the strongest influence on his career. The Brecht-Weill collaboration produced some of the most dazzling musical theater works of the twentieth century, among them Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny), The Threepenny Opera (Die Dreigroschenoper), The Seven Deadly Sins, and Happy End (though Brecht had only a nominal part in writing it). Working with Brecht was undoubtedly the most significant event in Weill’s professional life.

Mordden, like the Brecht biographer John Fuegli,1 does not have a very high regard for the German dramatist. He is almost obsessive in the vituperative manner with which he deals with Brecht’s vituperative manner (“the same ranting and shrieking associated with [Hitler]”, his body odor (“Brecht bathed so seldom and smoked cheap cigars so incessantly that he was all but unbearable in the physical sense”), his left-wing politics (“a foul piece of grownup propaganda”), and his egotism (or “drama-queen personality”). He concludes:

Brecht never stopped stealing, never stopped screaming, and never stopped stooging for the totalitarian crushing of the human spirit, as long as the crushing was performed by communists instead of Nazis.

He is equally dismissive of Brecht’s wife, Helene Weigel, whom he calls “the least attractive of Brecht’s Eves in every sense. A talented performer but an angry loon whose only content was communist fanaticism….” He oddly neglects to mention that Weigel was a lot more than talented—she was a superb German theater artist, the creator of Mutter Courage’s trademark “silent scream.” It is true that Weigel served as a “kitchen slave” to Brecht in his Hollywood years, while her husband continued to accumulate mistresses, whom Mordden (like Fuegli) believes wrote a lot of his plays. Mordden also argues that it was the “fanatical” Weigel who converted the “progressive” Brecht to communism (she certainly contributed to the failure of Happy End by reciting communist propaganda aloud at the curtain call).

Brecht did indeed display most of the defects attributed to him here, including a notorious disinclination to criticize the Stalinist tyranny. But the poet in him was always battling with the ideologue. With a few exceptions, some of his minor Lehrstücke (learning plays), for example, his work is too complicated to be reduced to a partisan agenda, and his plays rarely display the kind of inflexible political reductionism associated with Party dictates. (More typical are his ambiguous climaxes like the famous “Help” that ends The Good Person of Szechwan, or the finale of Mother Courage when the title character, having lost all of her children to the Forty-Year War, drags her cart around the stage in ever-widening circles.) For a more detached view of Brecht’s achievement, readers would be advised to turn to scholars such as Eric Bentley (whom Mordden mentions only once) and Martin Esslin (also mentioned once). It was Bentley who appropriately compared Brecht to the poet Dubedat in Shaw’s The Doctor’s Dilemma: “A scoundrel but an artist.”

Mordden is occasionally willing to concede some value to the Brecht-Weill partnership, sometimes even to Brecht’s genius. But he is much more concerned with the defects in Brecht’s character, charging him with being a “destroyer of productions,” though it was Brecht who founded and directed the Berliner Ensemble from 1949 to 1956. If Brecht had contributed no new plays to his theater, he still led a brilliant acting company and mounted productions rarely paralleled in his time.

For all Mordden’s lip service to Brecht’s talent, he seems impatient for Weill to divorce this Weimar deadbeat and remarry the healthy muse of American musical comedy. Despite his familiarity with German culture, Mordden has written most of his previously published work on Broadway musicals, including a six-volume history of the genre, from the 1920s through the 1970s, not to mention a book about Florenz Ziegfeld. It’s clear what this author’s musical ear prefers; and although he can praise Weill’s more serious Weimar achievements, he is more concerned with defending him against charges of Broadway commercialism. He wants to explain, for example, why Lee Strasberg, who directed the Paul Green–Kurt Weill Johnny Johnson for the Group Theatre, considered it “a play without music”: “It was mandatory at the time for anyone with intellectual pretensions to scorn musicals as meretricious.”

I’m not prepared to defend Lee Strasberg, who was probably tone-deaf, but as an old member of this intellectually pretentious club (formerly known as “highbrows”), let me say that we never considered musicals “meretricious.” (I’ve written three of them myself.) We considered an awful lot of them underachieved and overpraised. Intellectuals are usually eager to endorse the union between high art and low art (as personified, for example, by Shakespeare, Molière, Charlie Chaplin, Samuel Beckett, and Brecht–Weill—and in the world of musicals, the Sondheim–Gelbart–Shevelove A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum). What doesn’t rouse so much enthusiasm is Broadway commercialism and middlebrow pretension.

Advertisement

Mordden typifies the overinflation of the Broadway musical’s reputation when he compares, for example, “the [revolutionary] flowering of the musical” to “the overthrowing of the Russian autocracy.” What next? The Battle of Lexington? The storming of the Bastille? The entertainment value of the musical and, in rare cases, its artistic value (the Lerner–Loewe My Fair Lady, for example, or the Boublil–Natel–Schönberg Les Misérables, or Sondheim’s Gypsy and Passion) are hardly to be denied. But most Broadway musicals—a form frequently praised for being “America’s native art form”—would be more accurately categorized as a species of popular entertainment, similar to the Viennese operetta from which it sprang, and, in more recent productions, to the spectacles associated with the Circus Maximus.

Kurt Weill’s book writers and lyricists when he finally emigrated to this country in the early Thirties included a lot of very talented people, among them Franz Werfel (The Eternal Road, 1937), Paul Green (Johnny Johnson, 1936), Elmer Rice and Langston Hughes (Street Scene, 1946), Moss Hart and Ira Gershwin (Lady in the Dark, 1941; The Firebrand of Florence, 1945), S.J. Perelman and Ogden Nash (One Touch of Venus, 1943), Alan Jay Lerner (Love Life, 1948), and, most compatibly, Maxwell Anderson (Knickerbocker Holiday, 1938, and Lost in the Stars, 1949). It was with Anderson that Weill wrote some of his most bewitching Broadway music, notably “September Song” from Knickerbocker Holiday, and the title number of Lost in the Stars.

But virtually all of Weill’s American songs are invested with a bittersweet melancholy that you will not often find in his early orchestral compositions or in his work with Brecht. This quality makes his songs appealingly wistful but somehow lacking in edge. Just compare the morbid ruthlessness of “Pirate Jenny” from The Threepenny Opera (“Then they’ll pile up the bodies/And I’ll say,/That’ll learn ya”) with the spirited bounciness of “The Saga of Jenny” from Lady in the Dark (“Jenny made her mind up when she was three. She herself was going to trim the Christmas tree”). These two Jennys inhabit completely different landscapes.

Early in his book, Mordden writes,

A common interpretation of Weill reads him as a shape-shifter, working in prestigiously “difficult” political art in Germany and then, in America, going commercial, as if the political were inherently prestigious….

Incensed by what he later calls “the relentless hectoring by critics at the way Weill supposedly changes his style from uniquely German to stereotypically American,” he adds that this “ignores the central fact that he changes his style from work to work….” Mordden continues: “Yes, Weill was a shape-shifter; but throughout his career, not just when he crossed the Atlantic.” I think it is possible to agree with Mordden’s high estimate of Weill’s Broadway work, and still recognize that the music dramas he wrote with the immoral, malodorous, Communist stooge Brecht were deeper, darker, denser than anything he ever produced with his Broadway colleagues.

Indeed, Weill’s meeting with Brecht produced what many, including myself, consider the high point of twentieth-century musical theater (for Mordden, it is the moment when “Weill suddenly starts acting sexy”). Their work together culminated in one of the greatest modern operas in the canon, namely Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (1930). Even the Broadway-besotted Mordden has to concede for the sake of accuracy that Mahagonny is “Weill’s finest work,” though he is not altogether accurate about the opera’s American production history.2

Weill’s work on Mahagonny contains the same stylistic questions you find in all his Brecht collaborations—the minor key, the tinny syncopations, the spasmodic rhythms, the dreamlike jazz America, and the melancholy climax when Jimmy Mahoney’s life ends on the gallows (even Brecht’s occasional happy endings are bitter—as, for example, the finale of The Seven Deadly Sins, when the two Annas finally complete their “kleines Hause am Mississippi in Louisiana” by rejecting anything that might bring them emotional satisfaction).

Brecht believed that human beings were driven by greed and self-interest, which were reasoned and controlled, and by virtue, compassion, and sexual desire, which were more inherent human qualities, and this made your capacity to rise in the world subject to an ability to suppress your more generous emotional self. That is why his characters—the two sides of The Good Person of Szechwan, for example, Shen Te and Shui Ta, not to mention the two Annas in Seven Deadly Sins and the drunk-and-sober title character of Mr. Puntila (and His Man Matti)—are often split characters.

It is doubtful whether Weill shared Brecht’s sense of contradiction in human nature, though Lenya certainly pulled him apart from time to time. Mordden pays far less attention to Lenya’s professional life than he does to her husband’s, but his admiration for her career is, nonetheless, almost starstruck, possibly because he finds it so compatible with his aesthetic. He calls Lenya “the empress of Brechtian mischief,” and “a musical-comedy Mother Courage,” and reserves his greatest praise for the parts she played in Hollywood movies and Broadway shows. But her “Surabaya Johnny” from Happy End and her “Benares Song” from Mahagonny-Songspiel probe far deeper than the delicious turn she did as a lesbian double agent in From Russia with Love, chasing 007 around the room, kicking at him with a poisoned knife-blade hidden in her shoe. And her performance as the singing Anna I in the City Center Ballet version of The Seven Deadly Sins in 1958 left a far more powerful impression on many of us than her fine characterization of Fräulein Schneider in the Kander and Ebb simulation of Weimar culture in Cabaret, possibly because it was echt rather than echoed.

Speaking of split natures, I should say a few words about the author’s prose. It is as if two different people were writing his book. There are times when Mordden’s voice sounds like something overheard at a neighboring table at Sardi’s (“There was nothing in the European arts world like being the author of a smash-hit opera”). Sometimes it sounds like a press agent’s release (“That is the Kurt Weill we all know, leading his band of musical cutthroats in spoof operas that laugh about sex and tear down your heroes, Public Composer Number One on the Nazis’ enemies list”). When Weill falls in love with Lenya, Mordden writes, like a gossip columnist for Style, “He does everything but break into ‘Younger Than Springtime.’” Mother Courage, he says as if in praise, “unfolds as inexorably as anything by Sardou” (apparently he is unaware that Sardou was a manufacturer of cleverly constructed but generally lifeless Boulevard comedies and dramas).

And yet, despite the number of editorial errors and stylistic blunders scattered throughout the book, there are times when Mordden’s writing becomes almost elegant, as if a teacher of English composition had suddenly broken into his study and threatened him with a cane. Weimar Berlin, for example, the world of George Grosz and Fritz Lang and Marlene Dietrich, is hauntingly evoked. And he can be entertaining about the vagaries of German show business:

The Diva Walkout, along with The Other Diva’s Refusing To Sing a Solo Because It Is Beneath Her, The Mechanical Failure of a Special Effect, The Risible Vanity of the Leading Man, and The Kibitzers at the Dress Rehearsal Who Gleefully Predict the Greatest Flop in History were all part of a milieu that Weill was entering for the first time.

But he can also be tasteless and unfeeling: “Ira had been so crushed by the untimely death of his brother George that he had folded into retirement in Los Angeles as the Widow Gershwin.”

The mixture of clarity and vulgarity that permeates Mordden’s book on Weill and Lenya is the identifying mark of the middlebrow aesthetic. But even to use such terms as highbrow, middlebrow, and lowbrow these days is to suggest that one is a culture snob frozen in some prehistoric era. I think I can pinpoint a time when these distinctions began to blur, because I just came across a 1957 theater review by Diana Trilling in The New Leader in which she compared O’Neill’s Long Days’ Journey into Night (in the memorable José Quintero production) with the Lerner–Loewe musical My Fair Lady, and preferred the latter. “I have never admired the plays of Eugene O’Neill,” she wrote, “and I confess what is no doubt a morbid resistance to works of the imagination which deal with unpleasant themes.”

My old teacher Lionel Trilling’s continuing distaste for O’Neill (not to mention theater in general) was based on the playwright’s clunky, stumbling early plays, not the later masterpieces, which he never wrote about. But would he or Diana (his wife) have applied the same standards to novels with “unpleasant themes” such as Madame Bovary, The Possessed, or As I Lay Dying? When Diana eventually decided not to walk out on the O’Neill performance, she found the experience rather rewarding, though she wished the show had been a great deal shorter.

She concluded that “perhaps the best compliment I can pay O’Neill is to acknowledge that his autobiographical drama had for me an import almost as large and lasting as a superb musical comedy.” Regardless of the wit and artistry of My Fair Lady, to read a sentence like this, so condescending toward what is perhaps the greatest American play, is to watch a notable intellectual pretending to be, or being, a middle-class theatergoer from Morningside Heights. In this, she resembles an increasing number of educated people, perfectly capable of appreciating great literature, who put themselves in a Philistine mood when they visit the stage, choosing a Broadway musical with a Hollywood star, preferably with a lot of flying over the audience. And that is one reason why so much of our sorry theater seems so depressing and disappointing, and why so much of the writing about it does, too.

-

1

Brecht and Company: Sex, Politics, and the Making of the Modern Drama (Grove, 1994). ↩

-

2

After a disastrous off-Broadway run in 1970 directed by Carmen Capalbo and starring Barbara Harris and Estelle Parsons, the Yale Repertory Theatre did a full-orchestra production of Mahagonny in 1974. The translation by Michael Feingold persuaded Lenya to let us do the American premiere of Happy End (in 1975), even though it was a show she had previously banned. The success of the Yale Happy End led to its Broadway premiere (in 1977) featuring a member of the Yale cast, Meryl Streep. ↩