Following is an excerpt from a letter from George Orwell to Dwight Macdonald, written in December 1946, soon after the publication of Animal Farm in the US. According to the editor of the letters, Peter Davison, who also supplied the footnotes, Macdonald wrote Orwell that

anti-Stalinist intellectuals of his acquaintance claimed that the parable of Animal Farm meant that revolution always ended badly for the underdog, “hence to hell with it and hail the status quo.” He himself read the book as applying solely to Russia and not making any larger statement about the philosophy of revolution. “I’ve been impressed with how many leftists I know make this criticism quite independently of each other—impressed because it didn’t occur to me when reading the book and still doesn’t seem correct to me. Which view would you say comes closer to you own intentions?”

Orwell’s reply will appear in George Orwell: Life in Letters, to be published by Liveright in August.

Re. your query about Animal Farm. Of course I intended it primarily as a satire on the Russian revolution. But I did mean it to have a wider application in so much that I meant that that kind of revolution (violent conspiratorial revolution, led by unconsciously power-hungry people) can only lead to a change of masters. I meant the moral to be that revolutions only effect a radical improvement when the masses are alert and know how to chuck out their leaders as soon as the latter have done their job. The turning-point of the story was supposed to be when the pigs kept the milk and apples for themselves (Kronstadt).1 If the other animals had had the sense to put their foot down then, it would have been all right. If people think I am defending the status quo, that is, I think, because they have grown pessimistic and assume that there is no alternative except dictatorship or laissez-faire capitalism. In the case of Trotskyists, there is the added complication that they feel responsible for events in the USSR up to about 1926 and have to assume that a sudden degeneration took place about that date. Whereas I think the whole process was foreseeable—and was foreseen by a few people, eg. Bertrand Russell—from the very nature of the Bolshevik party. What I was trying to say was, “You can’t have a revolution unless you make it for yourself; there is no such thing as a benevolent dictat[or]ship.2

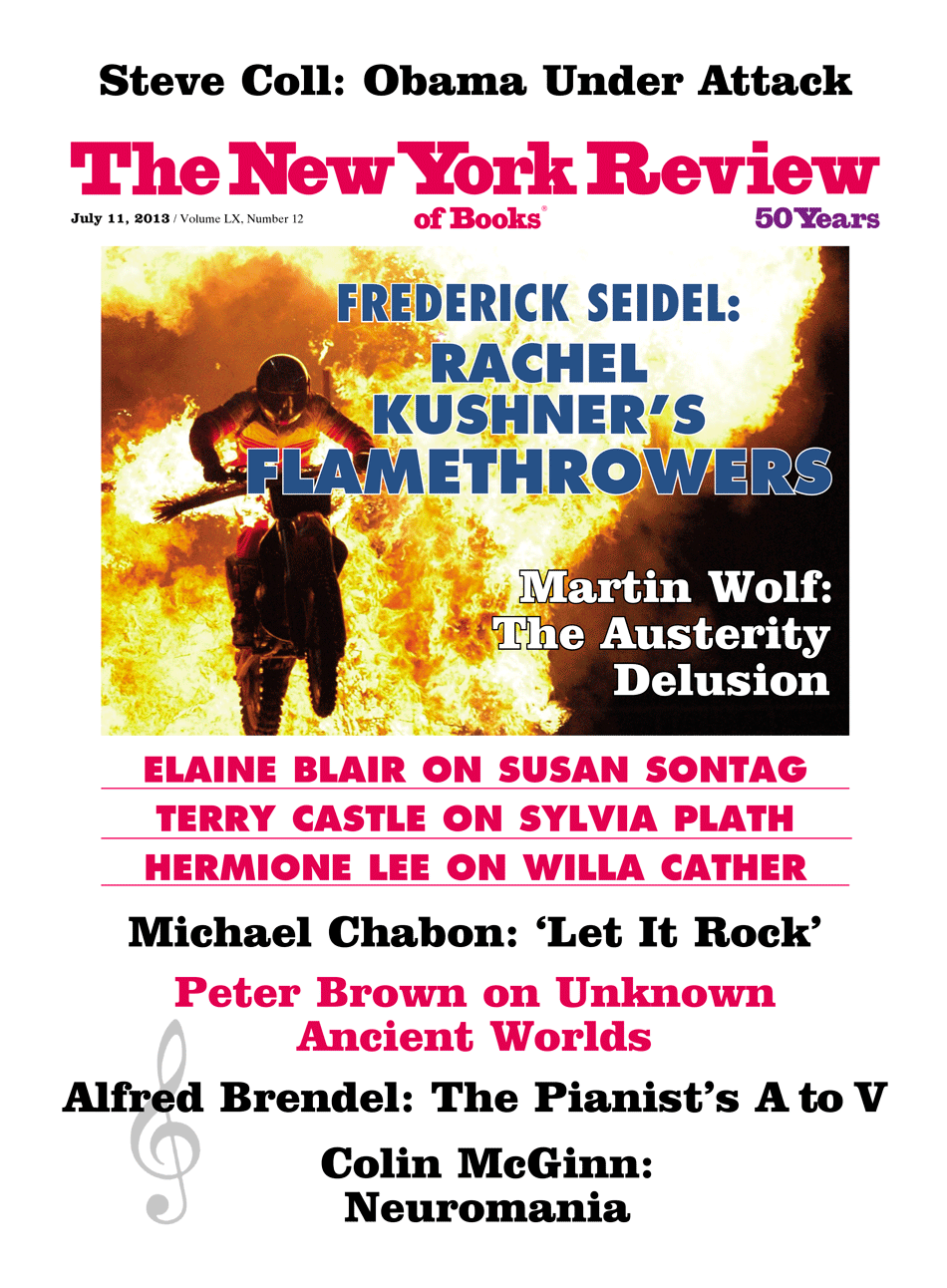

This Issue

July 11, 2013

A Pianist’s A–V

Hard on Obama

The Unbearable

-

1

Kronstadt, a naval base guarding the approach to St. Petersburg, a few miles from Finland, was established by Peter the Great in 1704. The turning point in Animal Farm is related to events that took place there early in 1921. Food shortages and a harsh regime prompted a series of strikes in Leningrad; in March the strikers were supported by sailors at the Kronstadt naval base. This was the first serious uprising not only by supporters of the Revolution against their government but by a city and by naval personnel particularly associated with ensuring the success of the 1917 Revolution. Trotsky and Mikhail Tukhachevsky (1893–1937) put down the rebellion, but the losses sustained by the rebels were not in vain. A New Economic Policy was enunciated shortly after which recognized the need for reforms. Tukhachevsky was made a Marshal of the Soviet Union in 1935, but two years later he was executed in one of Stalin’s purges. The fact that Macdonald missed the significance of the “turning-point” in Animal Farm may be the reason why Orwell strengthened this moment in his adaptation for radio, the script of which he was to deliver in a week or so. He added this little exchange:

CLOVER: Do you think that it is quite fair to appropriate the apples?

MOLLY: What, keep all the apples for themselves?

MURIEL: Aren’t we to have any?

COW: I thought they were to be shared out equally.

Unfortunately, Rayner Heppenstall cut these from the script as broadcast. ↩ -

2

When Yvonne Davet wrote to Orwell on September 6, 1946, she told him that the title initially chosen for the French translation of Animal Farm was to be URSA—Union des Républiques Socialistes Animales (=URSA, the Bear) but it was changed “to avoid offending the Stalinists too much, which I think is a pity.” ↩