Subhash Mitra comes home one day from his Rhode Island lab to an unexpectedly empty apartment and finds the bedroom table covered with the dark hanks of his wife Gauri’s hair. She’s chopped it all off with a pair of kitchen shears, and then taken the blades to her clothes as well, so that “her saris, and her petticoats and blouses, were lying in ribbons and scraps…as if an animal had shredded the fabric with its teeth and claws.” When she returns a few minutes later she’s dressed for the first time like an American, in pants and a breast-hugging sweater, but she can’t really be bothered to explain. “I was tired of it,” she says, that’s all, and sweeps the old things into the trash, while Subhash bites his anger down, unable to tell her how wasteful she seems, or how bad such “destructive behavior” must be for the child she’s carrying.

The moment pulls us within the bitter logic of the Mitras’ marriage and forecasts the eventual relations of this Calcutta-born pair with their daughter Bela, the girl who isn’t Subhash’s, and yet will be. But it also says a great deal about the deliberate restrictions of Jhumpa Lahiri’s own work. Because we don’t get the rage Gauri must have felt as she sliced through the cotton and silk, or the determined grimace—I’m inventing these details—on her face as the scissors met the resistance of her hair. Lahiri underplays it all. The scene she actually writes presents Subhash’s reaction to that earlier and unwritten moment of wreckage, and her prose remains unruffled. Gauri may burst beyond decorum. Her creator never does. Nothing extreme, nothing unmannerly; it’s all a little bit gray, as if the novel itself were as determined as Subhash to refuse any moment of emotional crisis.

That makes Lahiri sound cautious, and in reading her I have in fact sometimes wished she would break her own rules, and allow herself to flower into extravagance. Yet restraint has a daring of its own, and The Lowland is her finest work so far, rivaled only by the “Hema and Kaushik” stories in Unaccustomed Earth (2008). It is at once unsettling and generous, bow-string taut and much, much better than her episodic first novel, The Namesake (2003), in which an open ending fizzled out into inconsequence. At the same time, I expect it will prove her most controversial book to date, for its plot grows out of the Maoist-inspired Naxalite uprising that began in West Bengal’s Darjeeling district in the late 1960s.

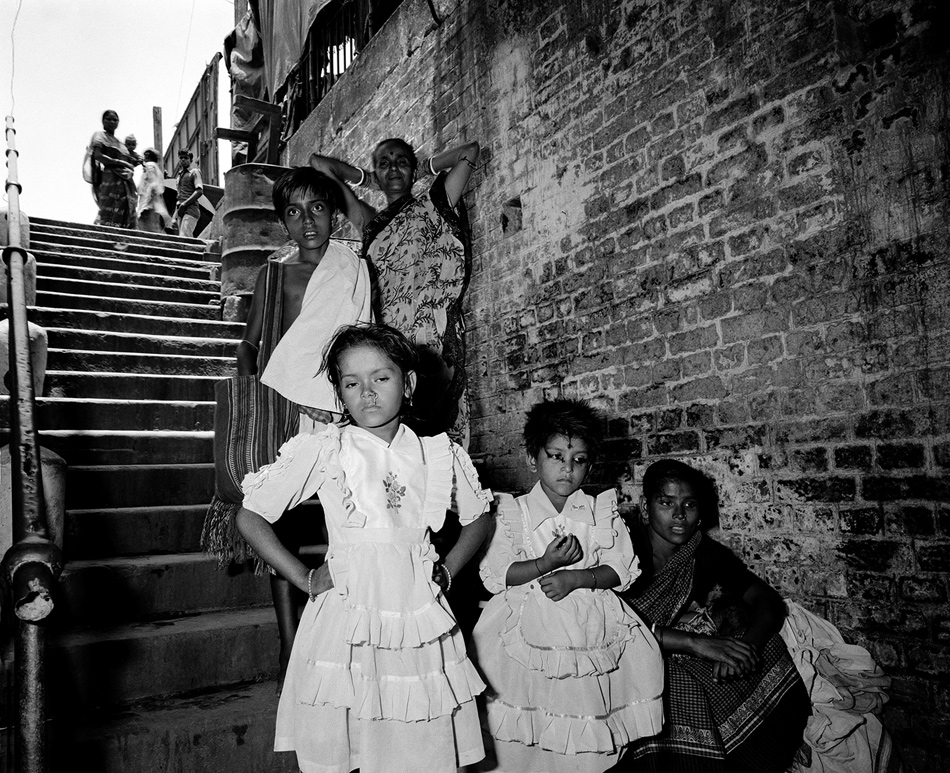

The Naxalites had their roots in the countryside, in the disputes between landlords and peasants, and even now remain a potent force in India’s tribal areas. They also appealed, however, to an urban intelligentsia, radicalizing those students, like Subhash’s younger brother Udayan, who could no longer abide the country’s poverty and corruption, and in the early 1970s their actions, along with the government’s smothering response, gave Calcutta its own years of lead. The Naxalites killed policemen along with some teachers and businessmen, and many people saw—see—them as terrorists. Others admired their idealism, regretting their tactics while sharing their goals, and still more were appalled by the scale of the state’s paramilitary reaction. Lahiri takes no explicit position, and reading The Lowland made me recall one of Stendhal’s most famous aphorisms: politics in a novel are like a pistol shot in the middle of a concert. They are entirely out of place but impossible to ignore, and though Lahiri herself has put those politics in, she also wants us to look away from them, to concentrate on the spectators instead of the struggle around the gun.

This book is a determinedly apolitical writer’s attempt to deal with an explosive subject, and some readers will think it quietist. They will miss the edge of impassioned engagement that they might find, say, in Arundhati Roy, and argue that with this material Lahiri should have produced a different kind of book. But there’s another way to put it. For though she deals more fully here than ever before with a specifically Indian subject, though the book both begins and ends in Calcutta and what happens there will forever mark its characters’ lives, The Lowland is written in an American vein.

The title comes from a few acres in the south Calcutta district of Tollygunge, a marshy spot that floods during the monsoon, growing so “thick with water hyacinth” that it looks solid. The surrounding neighborhood is one of “narrow lanes and modest middle-class homes,” and a good place for an uneventful childhood. Subhash and Udayan were born only fifteen months apart, shortly before the subcontinent’s 1947 independence, and their bond is so tight that their parents hold the older boy back so that they can start school together.

Advertisement

Subhash is the cautious one, who likes helping his father plant dahlias, and strives “to minimize his existence, as other animals merged with bark or blades of grass.” Udayan is in contrast “blind to self-constraints,” impetuous and charming, always arguing with his teachers and making his parents worry. But their voices are almost identical, and Subhash has “no sense of himself without” his brother; “each day of his life began and ended with Udayan beside him.”

The boys do well in school and go on to university, but they begin to separate when in 1967 the radio starts to carry a few news items from the Himalayan foothills, stories from a far-off village called Naxalbari. Local quarrels don’t normally merit much coverage. A sharecropper gets beaten, his family starves? No news there, but in this village the Communist son of a local landowner has taught the peasants to fight back. They burn records, they squat on the land from which they’ve been evicted, and they begin to carry red flags and weapons. A policeman is hit by an arrow; a riot is met by police bullets. To Subhash the revolt looks futile, but Udayan is stirred by the villagers’ show of resistance. He begins to quote Che Guevara, spends his days at rallies, and even drags Subhash along one night while he tags a wall, writing “Long Live Naxalbari” in English. The older brother doesn’t have the strength to resist, but he still manages to pose a question: “You don’t think what you’re doing is selfish?”

Udayan finds a job teaching high school, but the careful Subhash now makes a surprising declaration of independence. He applies to an American graduate school, and begins to study oceanography at an unnamed university in Rhode Island. At first the country scares him. Even that tiny state seems so large and so empty, and without his brother, Subhash’s sense of self begins to shake. Still, the New England coast has its magic, its fog and marshes and the majesty of a “slate-colored” heron, and it isn’t long before he begins to fall for this new land.

A letter from home does, it’s true, disturb him. Udayan has gotten married—a love match with the orphaned sister of a friend, a girl who “prefers books to jewels and saris.” Subhash has always believed that their parents would arrange their marriages; he’s drawn to Gauri’s smile in the enclosed picture, but is troubled by this new example of Udayan “getting his way.” Nevertheless the marriage seems to have settled the younger man—the couple moves in with his parents, and his letters now say less about politics. Then a telegram arrives: “Udayan killed. Come back if you can.”

But Subhash’s parents barely register his arrival. They ask no questions about his American life, and with their eyes “calloused by grief” they say nothing at all about what’s happened. Moreover they ignore their pregnant daughter-in-law, who now wears a widow’s plain white sari, and is no longer allowed to taste either meat or fish. It’s a sign of respect on which Subhash’s mother insists; he finds it demeaning and knows that Udayan would have as well. And in his parents’ silence he turns to Gauri to learn about his brother’s death. The police had come for him, she says, they marched the whole family away from the house and held them at gunpoint and threatened to shoot unless he surrendered, and then he burst up from beneath the water hyacinth in the lowland where he’d been hiding. His hand was bandaged, some fingers blown off by a pipe bomb, and they shot him in her sight. His body was never returned to them.

Subhash soon recognizes that he can do nothing for his parents, but he believes that “Gauri was different. Around her, he felt a shared awareness of the person they’d both loved.” His parents see her only as a reminder of what they have lost, and his mother looks determined to push her out, to get rid of her and yet keep the child. He wants her, and he also wants to help her, but he quickly realizes that she can only escape this deadened house if he marries her, if he follows his younger brother “in a way that felt perverse, that felt ordained.” Subhash will take her to Rhode Island and raise the child as his own; someday they will tell the truth, and someday, too, she might love him. Gauri accepts his argument but thinks that kindness has made him weak; when she lands in Boston she feels only “the reality of the decision she’d made.” It will take forty years for the consequences of that choice to work themselves out.

Advertisement

Lahiri was born in London, an intermediate stop on her parents’ westward journey from Bengal, and came to the States as a toddler. She has told a version of their happier tale in “The Third and Final Continent,” the last story in her first book, Interpreter of Maladies (1999), and her concern lies as much with that older immigrant generation as it does with her own. Here she limits herself to her characters’ voices and reactions, and avoids anything like a clinical language in describing Gauri’s enduring grief and what, after Bela’s birth, is clearly an untreated postpartum depression. She recovers only by retreating into a graduate student’s life of crumpled papers and unemptied teacups, resuming the work in philosophy that her first marriage had interrupted, and eventually writing a dissertation on Schopenhauer. With time Gauri surprises herself with desire and begins to sleep with Subhash; but neither he nor her daughter will bring her any moment of joy.

The prose in which Lahiri defines these lives is a bit different than that of her earlier books. In dialogue she now does without quotation marks, and though her sentences have always been spare, she shows a new reliance on sentence fragments, at the end of a paragraph in particular:

So many times Subhash and Udayan had walked across the lowland. It was a shortcut to a field on the outskirts of the neighborhood, where they went to play football. Avoiding puddles, stepping over mats of hyacinth leaves that remained in place. Breathing the dank air.

That train of gerunds provides something like a continuous present, pointillist and monumental at once, as though the image were carved. An almost Faulknerian moment of stasis—and yet impermanent too.

For Gauri will never get over her brief and forever vanishing life with Udayan. She will never put his killing behind her, but she does learn that “space shielded her more effectively than time…. As if her gaze had to span an ocean and continents to see.” Physical separation makes the past less present. Yet it’s always there, and she will finally need some distance not only from Calcutta but from Rhode Island as well. Subhash, a specialist in the chemistry of oil spills, somehow finds a job at a lab on Narragansett Bay. He builds himself into a modest American success, a good father too, and when Bela is twelve he takes her with him to India. They stay for six weeks in Tollygunge, and when they return the grass around their suburban house has grown waist-high. The windows are shut, the curtains drawn, and on the coffee table he finds a letter, written in Bengali so that Bela can’t read it. “I hope,” Gauri writes, that “you will tell her the truth. That I have not died or disappeared but that I have moved to California, because a college has hired me to teach.”

The years unspool. The father and the daughter grow distant, close, and then distant once more; the mother vanishes not only from their lives but even from the narrative itself. It will be decades before she is heard from. Lahiri covered a great span of time in The Namesake as well, but that bildungsroman had a linear structure: the life of Gogol Ganguli, as seen first from his parents’ point of view, and then his own. The Lowland has a far more complicated architecture, and the further one goes in it the more often its surface is broken by flashbacks or shifts in perspective. Gauri combs out her still-long hair in the bedroom in Tollygunge, Udayan beside her; it is 1971 and he asks if she regrets marrying him. But as he strokes her hair, it turns short and gray and coarse, and she is now “fifty-six, the years made present by virtue of the resilience they have taken away.”

Even to Subhash Calcutta seems ever-present, the old-world point of reference by which he measures the distance he has come. Udayan is everywhere in his mind, and the details of their boyhood keep “distracting him, like pieces of landscape viewed from a train. The landscape was familiar, but certain things always jolted him.” In fact Udayan is more vivid to him dead than he would have been alive, for Subhash knows that he must someday tell Bela that he isn’t her biological father, and dreads it. So the past ripples out. Lahiri will bring this broken family up to our own day, but still their lives are touched by an absent presence, by the younger brother listening to a 1960s radio broadcast, and all that happened because of it.

Yet while the politics of that period—the Naxalite movement, the repression that followed it—prove determinative, they aren’t what The Lowland is about. Lahiri concentrates instead on the survivors, those shaped by the dead man’s actions, and it’s crucial that she does not let us see him as the innocent victim of an extra-judicial murder. His killing may be horrifying, but he’s not just a graffiti artist; the police know the man they are looking for and what he has done. I said at the start of this review that Lahiri takes no explicit position, and yet the very structure of her plot does suggest an implicit one. “You don’t think what you’re doing is selfish?” So Subhash had asked, and the question will echo on as with each chapter we see the ways in which Udayan’s choices have helped deform the lives of everyone closest to him.

Few Bengali novels about the Naxalites have received an English translation, and of them the best-known is Mahasweta Devi’s Mother of 1084 (1974), in which an activist’s mother must identify his corpse at the police morgue; the number suggests the scale of the government’s reprisals. Devi’s tersely written pietà fuses mourning and witness, and I suspect that Lahiri was thinking of it as she worked. But it comes from another time and another country, and her own imperatives are different. Lahiri isn’t concerned with a structural analysis of oppression, or with the quarrels of ideology and commitment; she doesn’t indict India’s political class and isn’t much interested in the question of what is to be done.

She understands and indeed makes us understand why Udayan joins the Naxalites, but the issues themselves don’t matter to her as much as their consequences, the aftershocks felt over many years by the members of this new American family. What counts in The Lowland isn’t the fate of society but rather the individual life and the chance or pursuit of an ever-frustrated individual happiness. In its explanation of the private damage that may lie within the pursuit of social justice, The Lowland is above all a liberal or even a bourgeois novel. That won’t please everyone, but Turgenev among others would recognize the problem she defines, and in fastening on it Jhumpa Lahiri writes from deep within the guiding assumptions of Western realism.

Interpreter of Maladies had its initial publication in paperback, and its early sales and reception were modest. Its winning the Pulitzer Prize in 2000 was a surprise, albeit one whose merits the years have confirmed, but the genuinely astonishing thing was the commercial success that followed, the millions it then sold. One best seller leads to another, and for The Lowland Lahiri’s publishers have announced a first printing of 350,000 copies. To explain that kind of popularity it’s not enough to point to her artistry alone, and I’d like to know more about the interplay of marketing and demographics in building her audience. Still, quality is clearly a part of it. Fastidious, uncompromising, and yet clear, her books carry a note of accessible distinction that flatters the reader’s own taste.

For me the most curious thing is the degree to which her early work seemed instantly recognizable, placeable within a literary landscape. And not that of South Asian fiction in English; I mean something much closer to home. Switch the names in some of her stories and you can trick yourself into believing you’re back in Cheever country. Oh, not really. The relations of husbands and wives, parents and children, follow entirely different rules, and there’s not even much gin. Yet he would have recognized the way she shapes an ending or handles point of view, and seen her suburbs as descendants of his own. She seamlessly inserts new people—new manners, mores, material—into a traditional American form, and is acutely aware of her predecessors.

The epigraph and title of Unaccustomed Earth come from “The Custom-House,” Hawthorne’s sly meditative preface to The Scarlet Letter:

Human nature will not flourish, any more than a potato, if it be planted and replanted, for too long a series of generations, in the same worn-out soil. My children have had other birthplaces, and, so far as their fortunes may be within my control, shall strike their roots into unaccustomed earth.

Lahiri’s use of those words suggests a slyness of her own; her characters have had to come all the way from Bengal, but for Hawthorne the few miles from Salem to Concord were enough. Still, the irony seems fond, and in that choice of an epigraph I hear no trace of postcolonial subversion. It is instead a mark of affiliation—she links herself to an American past, she claims her place in its tradition. Sinking your tendrils down into a fresh soil may revive a worn-out history; a different crop can enliven an exhausted ground. Either way, an unaccustomed earth makes for new stories. Neither Subhash’s nor Gauri’s later lives would have been possible in India, even as their origins make Lahiri’s New England just a bit different than it was.

That, however, is the most optimistic of readings, and in her earlier work in particular Lahiri has often looked at the transplants that don’t take. Some lives that seemed workable in India cannot accommodate themselves to a new land; and between the generations too much remains unsaid, as though the immigrant had left her words behind along with so much else. In America Gauri abandons her daughter, and never even writes. The two will meet each other just once more, when Bela is forty, in a carefully plotted accident that to the reader will seem shattering and satisfying in equal measure, and the novel will then forgive the older woman for her failure as a parent. Lahiri makes us see why she does it. Gauri sees it too, but that doesn’t mean she will forgive herself.