George Balanchine had a hidden childhood. When he left his native Russia for Europe and the United States in 1924, his entire family stayed behind, and even letters between them were unreliable. Judging from what he later told friends and biographers, he didn’t remember much, though what he did recall fit neatly, perhaps a bit too neatly, in two halves. Balanchine thought of his early family life as mostly warm, even happy, and he recalled with nostalgia a lost imperial world. He was born in St. Petersburg in 1904, and his father was Georgian, charismatic, a composer; his mother was Russian, and she played the piano and made wonderful food; they were Orthodox and he loved church ritual. Ballet, and his training at the Imperial Theater School, were part of his sensual memory; he longed for the smells, sights, sounds of old Russia.

The break came with war, revolution, civil war, and the collapse of everything he had known. He was still a child—just thirteen years old in 1917—and he was cold and alone as his family moved back to Georgia while he stayed in (then) Petrograd, dancing in freezing temperatures, performing at Communist meetings, in cabarets and clubs, and was pulled into the vortex of revolutionary movements in art. He left the country with memories of imperial light and revolutionary darkness, formal beauty and its violent undoing. He loved Russia and hated the USSR.

In subsequent years, Balanchine rarely spoke of his family. Yet there were shadows: a picture propped on his bedside table in New York in the 1950s of his father, who had died in 1937; his overwhelming emotion in 1962 when his New York City Ballet toured the USSR, and his difficult reunion with his brother, the only surviving member of his immediate family. Not to mention the letters from his mother, who passed away in 1959, which he, a man who kept little, privately stowed away until his own death in 1983. But mostly he held his family at a distance. It is fair to say that he hardly knew them.

Until now. Elizabeth Kendall has unearthed the world of Balanchine’s childhood. For this alone we owe her a great debt: she has had to dig long and hard to come up with new official documents, invaluable family letters, and revealing and previously unknown facts. She has sought out every living member of the family and immersed herself in their lore and examined the scant sources from every possible angle. Where the facts fail, as they often do, she raises questions and fills in the picture with history. This is her real strength: at its best, her book is not only a portrait of Balanchine’s youth, it is a portrait of Russia in collapse—of the world that was dying as Balanchine was coming of age.

It is also equally about the ghostly figure of Lidia Ivanova, a forgotten dancer who drowned in 1924, a day before she was to leave the country on tour with Balanchine and a small company of dancers. Her death in a boating accident with “some young Bolsheviks,” who may or may not have been involved with the secret police, inspired poems, newspaper articles, a flurry of dark rumors that she knew something she shouldn’t have and had been murdered. She was a woman remembered more for her death than her life, although Kendall makes the case, largely unconvincingly, for “Lidochka” (as she fondly calls her) as a new kind of dancer and “lost muse” to Balanchine.

Indeed, she presents Ivanova as a key to Balanchine: a way to bring “into focus the figure of the ballerina who would define his career,” a symbol of the kind of women he loved, of the city he grew up in, of the politics that destroyed it—as they may have destroyed her too—and of the memories of death and loss that haunted his dances for the rest of his life. This is a heavy load for any young woman to bear—especially one that Balanchine himself barely ever mentioned.

The result is an important and exasperating book that veers between careful analysis and overzealous speculation. If Kendall weren’t such an accomplished historian, we might think her a little mad—or perhaps it’s that she is in love: not with Balanchine, but with his dances and the kind of women—like her Lidochka—she believes inhabit his ballets.

For the reader, this is a mixed blessing. Kendall’s detailed and inconclusive focus on the circumstances of Lidia’s death at the end of the book, and her determination to give Lidia—with scant supporting evidence—pride of place in Balanchine’s psyche and art, distract her, and us, from reflecting on the truly groundbreaking research her book contains.

Advertisement

Georgi Balanchivadze’s* father, Meliton Balanchivadze, was dedicated to three things: Georgia, music, and his own vast and disorganized ambition. Georgia meant the farmland in the west around the town of Banoja, where he was born, and the nearby city of Kutaisi where, following his own father’s footsteps, he attended Orthodox seminary before moving on to the capital, Tbilisi. Georgia mattered, Kendall writes, because the family history in the region was deep—Balanchine’s paternal great-grandmother was apparently a village elder who sang and performed on the chonguri, and his grandfather was a priest and schoolmaster.

For Meliton, though, Georgia was more than a place or a family heritage: it was a nationalist cause. He arrived in Tbilisi at the height of the “back to the people” movement that was inspiring research into native Georgian literature, music, and art, and he soon dropped out of the seminary and made music—Georgian music, and Georgian national identity—his life. In this spirit, he married a Georgian woman from back home, settled in Banoja, and had two children.

In 1889 Meliton left for St. Petersburg, sponsored by a local merchant to study music so that he could write the first great Georgian opera—a project that absorbed years of his life and was in a constant state of incompletion. There he started a new life and a new family with a younger woman, Maria Nikolaevna Vasilieva, Balanchine’s mother. Meliton was not, as Balanchine apparently later thought, widowed (Kendall produces evidence that his Georgian wife later petitioned the state to take his pension from Maria), and we don’t know if he ever got divorced—or indeed if he ever officially married Maria. No marriage certificate has been found, and Kendall tells us that according to christening documents, all four of their children (the first died in infancy and Georgi was the middle of the next three) were born to the “unwed” Maria, which would of course make them all, including Georgi, illegitimate. Meliton officially recognized the children in 1906, but the arrangements between him and Maria were clearly not entirely fixed or conventional.

Balanchine’s mother was herself probably illegitimate too, and Kendall believes she may have been a courtesan, although her childrens’ baptism certificates identify her as a former craftswoman. She had minimal education, wrote simply and with grammatical mistakes—but that’s about all we know of her background. She left few traces, and like many women of uncertain pedigree, Kendall suggests, she had both a fierce social ambition and a strong adventurous streak. She entered and won the lottery—which lifted her and her family into a new socioeconomic class—bought a summer dacha in the Finnish town of Lounatjoki in her own name (not Meliton’s), and having thus provided for herself, cultivated a self-consciously haute-bourgeois lifestyle: summers in the country, wet nurses, posed professional photos of her children in sailors’ costumes, piano lessons, nanny, tutor. In a sign of her status-conscious ways, Kendall says, the moment she could afford it she joined the costly Second Merchants’ Guild of Tsarkoe Selo, the summer residence of the tsars and many members of the nobility.

Meliton and Maria filled their life with parties, dinners, and festive events with Georgian music and musicians, composers, singers, all gathered at the house or dacha for “one big ongoing feast,” as Balanchine’s younger brother Andrei later recalled. The company was distinctly conservative, and Kendall reminds us that the Balanchivadzes were not part of the progressive cultural elite of Nabokov or Diaghilev—their circle was Orthodox and monarchist, men of music but also of church and state, with strong nationalist leanings. Balanchine’s godfather, for example, was Konstantin Konstantinovich Stefanovich, a high-ranking Interior Ministry official who came from a religious milieu and whose father was the dean of St. Petersburg’s imposing Kazan Cathedral, where Balanchine witnessed—and never forgot—the archbishop of Tbilisi (a relative, as it turned out) become an Orthodox monk. He prostrated himself, as Kendall describes it, “on the great cathedral’s stone floor as the cloth of black crepe was thrown over him to mark his worldly death, then rose, a new being.”

The family’s social position, however, was never certain—Maria and Meliton were both furiously improvising—and letters cited by Kendall from Meliton to Maria from 1910–1911, as he squandered their lottery wealth in unsound business ventures and struggled to keep a financial foothold, reveal his fears that the whole thing might crumble: “I feel like I am throwing away my most precious thing—my family.” It did of course crumble, and he ended up briefly detained for unpaid debts—the children were told he was away collecting music, although it seems he was also briefly back in Georgia celebrating his birthday with his other family. Maria held the house together, with help from her sister, growing vegetables in her ample garden, cooking and caring for them all. In Balanchine’s memory his happiest childhood years were these, when he lived in the countryside in a household of women.

Advertisement

Even when he moved on to the Imperial Theater School in 1913, these women followed him. Here Kendall’s evidence does not seem to support her somewhat overwrought conclusion, or Balanchine’s own memory, that his mother’s decision to leave him abruptly at the school the day he passed his audition was “probably…the greatest trauma of his life, greater even than revolution, emigration, and the later financial and emotional ups and downs of a roving choreographer.” The records she produces show that he returned home for holidays and spent many weekends at a relation of his mother’s, “Aunt” Nadia, who lived in St. Petersburg. Indeed, during the chaotic years of the war and revolution, her home became a kind of family gathering point. And in the years after the Revolution, Maria did not desert her son when the rest of the family returned to Georgia. Kendall has evidence that, to the contrary, she moved to the city and took an office job, staying nearby, perhaps for her own reasons too, until 1921 when Georgi graduated. Only then did she join Meliton and the rest of the family in Georgia.

Still, and this is what comes across most clearly in Kendall’s account, it was a fragile, somewhat chaotic world, and even if Balanchine was unaware of the details at the time, he would almost certainly have felt the tremors and intuited the gaps, as children always do. As a father Meliton may have been fun and charismatic but he was also impulsive and unfocused, and often not there; in any case, he seems to have shown little confidence in his middle son. Why, to take a vexing point, did he settle for sending Georgi to dance school in 1913 when the boy’s real interest—like his father’s and his mother’s and for that matter his brother’s—lay in music, the one thing that was of indisputable value to them all?

As Kendall points out, Georgi’s childish letters to his father while he is studying ballet are heartbreakingly full of news about music, but rarely mention anything about his own pursuits in dance. A letter from his father in 1919—too late—imploring Georgi to become a musician (like his brother) rather than a dancer must have stung, coming as it did from a father who had by then managed to bring all of his children, except Georgi, to join him in Georgia. Meliton loved Georgia and he loved music, but he withheld them both from Georgi, one reason perhaps that these two things would later become such touchstones in Balanchine’s own life: he was always as much musician as choreographer, and he forever imagined himself Georgian, even though (until 1962 and then only briefly) he never set foot on its soil.

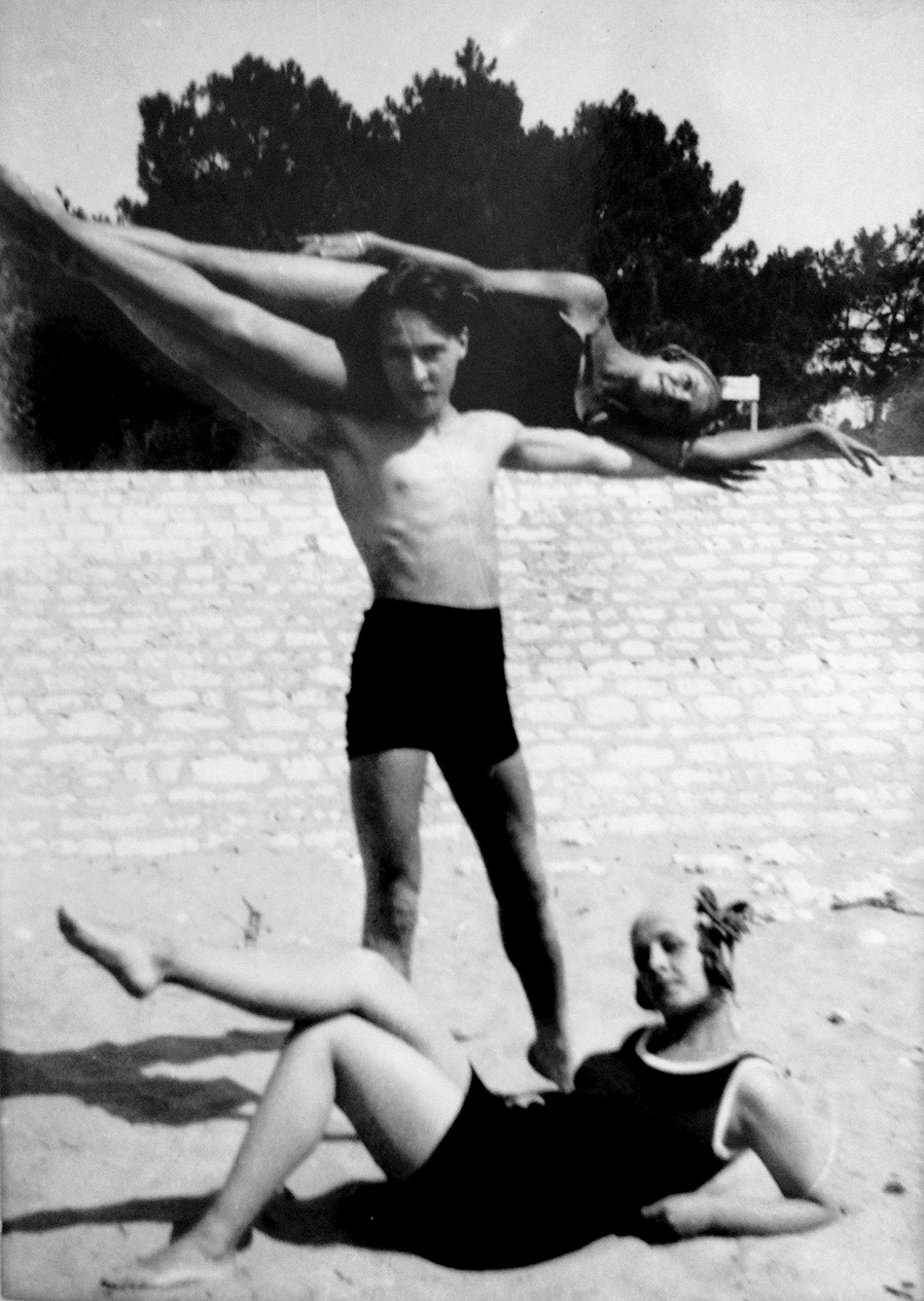

As for his mother Maria, whose image in photos appears so fragile and wispy, Kendall helps us see just how independent-minded but also vulnerable she must have been. And it is certainly true, as Kendall insists, that many of the women Balanchine would later surround himself with bore a resemblance to her: his dancers, his loves, his wives were almost all free-spirited bohemian women with none of the advantages of high birth or education and were unbound by social convention and traditional ways. Balanchine later liked to tell his somewhat mystified American dancers (he was only half kidding) to be like the comic book character Wonder Woman, who was invented during World War II as a fighter: strong, sexy, on her own, a woman from nowhere.

When World War I began in 1914—Balanchine was ten—the Theater School, like so many imperial institutions, turned a blind eye and went blithely on. Discipline and rote routine can be a form of denial, and ballet’s rituals, not unlike those of the imperial household itself, served this purpose for a time: every moment and every detail of life were safely regimented—waking, washing, eating, exercise, music, study, sleep, and above all, the absorbing mechanics of how to move one’s body to music. Meanwhile, the streets outside were full of chaos, violence, and death. Army conscripts flooded into the city; makeshift regimental barracks were erected and drills conducted in neighborhood squares—including the square outside the former Maryinsky Theater. Soon, refugees were streaming in from everywhere, hungry and in desperate search of food and shelter.

By the winter of 1916 food and fuel were in short supply. Balanchine and his friends sorted bandages for soldiers in their spare time and went without sugar once a week, but kept dancing. His family had meanwhile dispersed, and Kendall has tracked them all: his sister Tamara had been sent to Meliton’s brother and his wife near Moscow, Andrei was in Petrograd with their aunt, and Georgi’s mother was working at a hospital for wounded soldiers.

Meanwhile, as the government and the city reeled, Balanchine (by now age twelve) and his peers continued to be escorted to the theater in golden coaches—they called them “Noah’s Arks”—to perform in nineteenth-century fairy-tale dances such as The Sleeping Beauty. That December, in the midst of strikes, inflation, famine, and devastating war losses, young Georgi was escorted with his classmates to Nicholas II’s richly decorated box at the theater; he stood in awe of the tsar and received a box of fancy chocolates.

In February 1917, unrest turned to revolution as some 90,000 workers, soldiers, and women flooded the streets of Petrograd. Events unfolded in the ensuing weeks and months with terrifying speed and Kendall moves us swiftly along several intersecting paths: politics, ballet, and the chaotic efforts of the Balanchivadze family to relocate to Georgia. A bullet finally smashed through the windows of the Imperial Theater School, and armed revolutionaries searched for monarchists among the adults as the children cowered in confusion and fear. The tsar abdicated; the school closed; the theater closed (placards at the door: “Defend this building as national property!”); and when they both reopened, intermittently in the case of the school, everything had changed.

By April, the façade of the former Maryinsky was covered in red flags, and speakers on wooden platforms in the square outside harangued the crowds. Inside, the imperial portraits and double eagles in red plush cloth were gone, ushers wore gray instead of gold, and the heavy old stage curtain emblazoned with imperial eagles was replaced with a simpler one—light, white, Grecian—from a production by the radical theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold (later beaten and murdered on Stalin’s orders). The tsar’s box and the once-glamorous parterre were now inhabited by workers, revolutionaries, and even by worn men returned from Siberian prisons (others sold their free tickets to the dispossessed old elite). In winter, Kendall reminds us, the theater was barely heated, and audiences brought coats and blankets and boots; the dancers, in their skimpy costumes, wrapped themselves in wool in the wings, and slid briefly out of their cover as they made their stage entrances. The students, Balanchine among them, still danced their customary bit roles, but now they came to the theater on foot or in old wooden carts pilfered from a theatrical storehouse, re-outfitted as rickety carriages and pulled by a half-starved nag.

The Balanchivadze family was by now in complete disarray. When the school initially closed, Balanchine found his way to his aunt’s apartment; Andrei was there too and Maria eventually joined them. After the Bolshevik takeover and as violence and chaos escalated in Petrograd and across the countryside, Meliton wrote from Georgia on November 12, 1917: “Wife and Children my Dears, how are you living in this terrible time?” He worried that the situation in the city was too dangerous and urged them to come: “Leave all the things in Petrograd, we can worry about them later.”

The family was against the Bolsheviks and for Georgia, and Meliton reported that he was working, setting up music schools, staging operas, engrossed in the musical life of what he no doubt hoped would become a new nation. His brother Ivan would die fighting against the Red Army. Andrei and Tamara managed with difficulty to join their father. On October 8, 1918, Georgi and Maria received an exit passport, No. 4385, filled out, according to Kendall, in Georgi’s hand, allowing them to travel to Georgia to join the family.

They didn’t go. Why? We don’t know, but instead, Georgi returned to the ballet school when it reopened. It was a decisive moment. The winter of 1919 in Petrograd was unforgivingly cold and cruel, the city a frozen mass with no heat. Making matters worse, windows were routinely knocked out to remove the ledges and any other piece of wood that might burn for a moment’s warmth, leaving the inhabitants agonizingly exposed. In the streets that Balanchine now traveled violence and terror were rampant and unpredictable—Reds, Whites, Greens, anarchists (Blacks), nationalists were all at war—and starvation and death commonplace. In the three years between 1917 and 1920, the population of Petrograd fell by two thirds.

The school struggled. Its ranks were reduced and persistent fuel and food shortages (a menu of blackened potatoes) made study difficult, as did painful skin boils and blotches from malnutrition—Georgi was covered in them. Before beginning their morning studies, the children carried logs, when they were lucky enough to have them, into the dance studios and shoveled them into wood-burning stoves that belched smoke out of open windows. Meals were prepared by rotating teams of students, coordinated by a committee—the UchKom—run by the boys, including Georgi; they carefully measured and weighed the portions—one eighth of a pound of bread a day for each.

By now, Kendall has introduced us to the full cast of characters steering this unlikely little ship, including the old (by now former) priest, Batiushka Pigulevsky, who found the boys odd jobs to do under cover of night, sawing fence-wood, or cleaning up vast mounds of garbage and wreckage in exchange for bread, frozen potatoes, herring heads, anything. Andrei Alexandrovich Oblakov, a former dancer who had performed with Diaghilev in Europe, became director of the school in 1919. His small apartment was crowded with books and he introduced Balanchine and anyone who was listening to contemporary literature and poetry, including the work of Mayakovsky—another Georgian.

Which brings us to the other revolution: the one that happened in Balanchine’s mind. It was intellectual and artistic, and it hit him hard from many directions at a critical moment, as he was becoming a man. A key figure, as Kendall shows, was Anatoli Lunacharsky, Lenin’s commissar of education, “poet of the Revolution,” savior of the ballet and the former Imperial Theaters, and also—crucially—the political muscle behind the radical theatrical experiments of Mayakovsky, Blok, and Meyerhold. It was Lunacharsky, with his ideas of a civic religion of the arts, who spoke at the reopening of the dance school in 1918, with Balanchine probably in attendance. And it was Lunacharsky who in 1920 was behind The Storming of the Winter Palace, one of many epic public spectacles in which the artists of the former Imperial Theaters participated, in this case, a reenactment of the events of 1917 featuring 10,000 artists, soldiers, sailors, and an audience of some 100,000 in Palace Square.

In 1921 Lenin introduced the New Economic Policy, allowing a mixed economy with small private enterprises. As the economy improved, theater and nightlife exploded. Ever in need of money, Balanchine danced and choreographed in cafés, cabaret halls, movie theaters. Around this time, he also met and in 1922 married Tamara Geva, whose father, Levkii Zheverzheev—half Tatar, half Turk, Muslim-born—was deeply involved in avant-garde theater and art. Balanchine met Mayakovsky, whose work he liked to quote at the time and in years to come. He had already briefly worked with Meyerhold, whose interest in biomechanics and in commedia dell’arte was part of an ongoing effort to overturn theatrical conventions. In this overheated political and artistic climate, ballet as he had known it was no longer acceptable.

Georgi, Kendall writes, joined a small group of progressive-leaning young dancers to work on Fedor Lopukhov’s The Grandeur of the Universe, the first plotless “symphonic” ballet—one critic called it the “Black Square” of dance after Malevich’s 1915 painting. That same year, he saw Kasian Goliezovsky’s erotic and gymnastic dances and after the show he and friends talked with Goliezovsky into the night. He went further afield and started his own company, the Young Ballet. It was collectively run and any proceeds were shared, each according to need. On June 1, 1923, the company opened at the hall of the former City Duma, a venue that had also featured lectures by Lunacharsky, Mayakovsky, and the poet Sergei Esenin.

For Balanchine, this embrace of the revolutionary avant-garde was a significant break—from his family, his past, his training. The Orthodox and Georgian nationalistic milieu of his upbringing, which had neatly dovetailed with the traditions and military precision—the orthodoxy—of the imperial ballet, was not exactly gone, but it was set far to the side, at least for now. He did not—and would never—embrace the Revolution, as Lunacharsky, Meyerhold, and Mayakovsky had all enthusiastically done; but he did take on a radical agenda for art, and the politics were not easily separated out and discarded. The New Economic Policy (NEP) complicated matters. Kendall convincingly shows that the Young Ballet fashioned itself in part against the crass commercialism and materialism—the blatant NEP capitalism—of those years.

As a dancer, Balanchine stayed close to the spirit of his father: he loved national dances and excelled in bravura demicharacter roles—his graduation piece in 1921 had been a Lezhinka, a rousing Georgian folk dance. Yet as Kendall points out, his choreography was mostly the opposite: serious, about love and above all death. He used music by Chopin—not the lively piano études, but the “Funeral March.” We don’t really know what this dance looked like, but at one point three men carried a woman (Tamara Geva) lying flat on her back as if dead, in procession, lifting her up over their heads as they approached the front of the stage, a ritual all too familiar to the soldiers and sailors and people in the audience of the ravaged city.

In 1923 Balanchine staged a production of Alexander Blok’s poem “The Twelve,” with no music and fifty singers rhythmically chanting verses—a technique Meyerhold had also used—in a ritualized spectacle that must have accentuated the raw irreverence and sexualized violence of the text. Blok had written the poem in 1918 at the peak of his own revolutionary enthusiasm, before his disillusionment, illness, and death in 1921. Kendall unfortunately does not go into this, but choosing Blok was itself a statement, because of the poet and the poem, but also in view of Blok’s mystical experiences and writings on an idealized Beautiful Lady, another theme that would preoccupy Balanchine. Where exactly did Balanchine stand in relation to Blok, Mayakovsky, Meyerhold, and others at the time? Kendall doesn’t quite say.

Her final chapter turns instead to the theme of death and “corpses” in Balanchine’s future work, and the place of Lidia Ivanova and a dying St. Petersburg in his imagination. Here she goes too far, speculating for example that Serenade, which premiered in New York in 1934, was a kind of ode to Lidia. When Kendall describes the final moments of the ballet (a woman standing upright, lifted on high, and carried into the light as she arches back with arms open in surrender) and asks, “Is she Lidochka?” my answer—based on her book—is no, she’s not Lidochka or anyone else. She’s the idea of loss and leaving, of fate and time and mortality, rendered in dance.

Something seems to have developed inside Balanchine that gave him an unusual tolerance for loss and emotional upheaval—the detachment of the survivor perhaps—and an ability to sweep away feelings when they overwhelmed him, and to start over. This was the idea of the blank slate, and it is the story, and the discipline, of his Apollo, created in Paris in 1928—after he had left his homeland: starting from nothing, every night, white on white, and using ballet to do it. The impulse behind the dances reflected his inner life: an emotional detachment that was at once a retreat and a purification—not depression really, but something more decisive and willful, his own personal and internal revolutionary attitude.

We now know that Balanchine did not have a solid childhood disrupted by the war and revolution; it was uncertain from the start, defined by gaps, breaks, “in-betweens.” Neither his mother nor father had clear identities. They were not aristocrats, not bourgeois, not demimonde, not Russian, not Georgian. He was not sent to the military or to music, but to dance—and so he lived between them all. Even ballet school didn’t help: he wasn’t a particularly good dancer.

Amid the disruption and brutalizing experience of war, revolution, and civil wars, we find a picture of a child and young man whose inner and outer worlds, family and history, offered him little by way of protection. He had only one sure platform to stand on: ballet. And even that did not hold. It is not that Balanchine grew up too fast—lots of people do—but that he grew up surrounded by violence; and perhaps more troublingly still, the destruction and death that engulfed his city and his life came with—and even in part caused—an artistic vitality that was central in everything he went on to do.

Later he had nostalgia, memories, and yearning for what he had lost and in some way never fully had: Russia. But the revolution was inside him too, and if in his memory they were opposed, this may have been more a sign of pain than forgetting. Nostalgia implies something or somewhere that still exists and might be retrieved or returned, Prospero-like, with magic and art. That was an illusion Balanchine both loved and knew to be false. His own childhood had proved it.

This Issue

October 24, 2013

Terror: The Hidden Source

A Different Kafka

-

*

Balanchivadze was changed to Balanchine in Paris by Diaghilev in the 1920s. ↩