It was a bright cold day in 1984 and a conservative American friend was berating me about my article in The New York Review. How dare I even think of comparing US policy in Central America with Soviet policy in Central Europe? What kind of whining Chomskyesque relativist had I become? We were just beginning a long car journey. I was his prisoner. On and on went the interrogation.

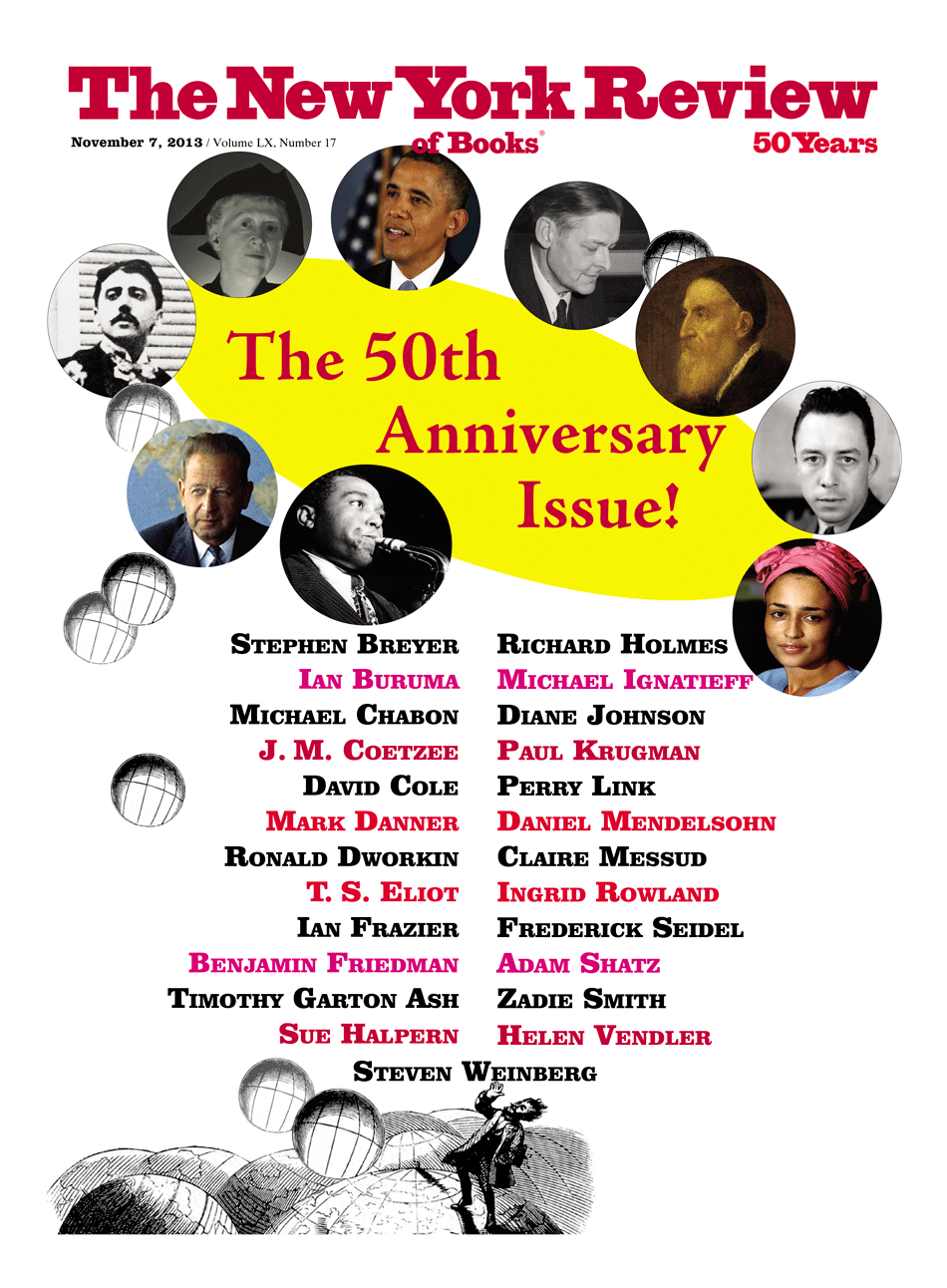

This memory returned unbidden to my mind when I was contemplating the subject of this essay, which is the political world around The New York Review over the fifty years between the first issue, published in 1963, and this fiftieth anniversary one. For the theme of that 1984 article,1 my first contribution to this journal, spoke directly to what seems to me one characteristic way in which the Review has responded to the political challenges of the late-twentieth and early-twenty-first centuries.

Now it would, of course, be not merely absurd but insulting to many other highly individual contributors, living and dead, to pretend to summarize their more than 15,000 contributions over fifty years. Yet I do detect an approach that runs through many, though obviously not all, of the political articles that have appeared during that period. Since it is an approach with which I strongly identify, and to which I have contributed for nearly thirty of those years, I will deliberately say “we.” That “we” carries a warning. This is just one writer’s partial and personal view of a vast political and intellectual landscape. It is an attempt to explore, by the light of the Review, what has remained the same and what has changed politically over this half-century—and to say something, in the end, about challenges the next years will bring.

So think of the Review as a lighthouse at the center of the Western world. Time-lapse photography reveals how the world has changed under its steady illumination.

Yet first we have to understand the specific quality of the light beam. This is what I will, arbitrarily, but not without a mass of evidence from many thousands of archive pages, call a New York Review approach to the world. Consistently, over five decades, this journal has published critical essays, reportages, and analyses of totalitarian and authoritarian states, whether their rulers were opposed to or currently aligned with the United States: friendly dictatorships in Latin America; the Soviet Union, subsequently just Russia; China; South Africa; Eastern Europe, when it still existed as a geopolitical entity; Iran; Nicaragua; Iraq; Vietnam; Egypt.

These exposés have been written by dissident writers inside those countries and Western writers traveling through them. In a text published in the Review in 1964, explaining why he had rejected the Nobel Prize for literature, Jean-Paul Sartre sniffily remarked that the prize stood “objectively as a distinction reserved for the writers of the West or the rebels of the East.” As if those Eastern rebels might not be writers too, and Western writers also rebels. (Boris Pasternak not a writer? Heinrich Böll not a rebel?) Across fifty years we find in these pages the writer-rebels and rebel-writers from East and West. Every one has an individual voice and view, but if I were compelled to summarize the shared starting point of this half-century of political reportage, analysis, and dissent in just two words, those two would have to be “human rights.”

Equally characteristic—and the other edge of the same razor blade—is a persistent, stubborn strain of criticizing US policy, at home and abroad, whenever it falls short of the high ideals proclaimed in this country’s own Constitution and by its own leaders: continued racial segregation in the Review’s founding year of 1963; the war in Vietnam and bombing of Cambodia; Washington’s support for the contras in Nicaragua; Bosnia, as an American sin of omission; retrograde Supreme Court decisions such as Citizens United; Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib; mass surveillance by the NSA. “We have got ourselves a moral monster for a President,” begins a 1973 article by I.F. Stone.

Thus, the Review has, at its best, followed the principle promoted and exemplified by George Orwell (notably in Homage to Catalonia) that the political writer has a duty to be especially astringent in identifying the faults of his or her own political side. In my experience, this has had a notable effect abroad: precisely the fact that Western writers in journals such as this have been so outspokenly critical of the West in general, and American writers of the United States in particular, has enhanced the credibility of the West and the United States. Were I a Parisian lover of the sweeping simplification, I might write (for preference, in French) that the more The New York Review has criticized the abuse of American power, the more it has strengthened American power. If you want more pedestrian, Anglo-Saxon explicitness, add “hard” to the first mention of power, and “soft” to the second.

Advertisement

Also characteristic, and unsurprising in a journal at the frontier between literature and politics, is an Orwellian focus on the political abuse of language. We think immediately of Václav Havel’s explorations of the systemic mendacities of Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe, or Nadine Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee on apartheid South Africa, but the West has also contributed its smaller quota of newspeak. Browsing through old issues I chance, for example, on a short piece from 2003, excoriating CNN for parroting the ghastly, death-concealing euphemisms of the US military’s Centcom, including a description of Iraqi units being “attrited.”

If we believe that we should “speak truth to power,” the word “truth” in that phrase needs to be more closely defined. In his 1967 essay “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” Noam Chomsky quotes Martin Heidegger’s self-indicting declaration in 1933 that “truth is the revelation of that which makes a people certain, clear, and strong in its action and knowledge.” There are also the (often mutually incompatible) revealed truths of different religious faiths. These are not what we mean. We mean the more modest, skeptical, always self-questioning truth that is based on evidence, fact, and reality.

There are other ways of describing this combination of value system and method. We could call it “liberal,” frankly defying the grotesque metamorphosis of that word in the political rhetoric of the United States over precisely the period of the Review’s existence, such that in everyday American political (ab)use today the word “liberalism” has come to denote some devilish mixture of big government and fornication. A telling symptom of this semantic poisoning is that American politicians—including Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton—who obviously are liberal, in the good, time-honored sense still prevalent in British English, fear to use the L-word.

We could also call it Applied Enlightenment. Indeed, this journal has been—not always, to be sure, but in very large measure—the vehicle for a modernized version of the European-American Enlightenment (as well as publishing some of Isaiah Berlin’s strongest essays on thinkers who challenged that Enlightenment). Many of its contributors have both applied and extended the original Enlightenment principles of equal individual human liberty and dignity under law, at home and abroad, and explored the social and economic conditions that are an essential complement to those civil and political rights.

Meanwhile, the whole community of Review writers and readers has been a contemporary equivalent of the Enlightenment’s “republic of letters.” It has been a surprise to discover, at a series of recent conferences organized by the Review, that many longtime contributors had never before met in person, but merely read each other for years, and perhaps corresponded, publicly and privately—exactly like those seventeenth- and eighteenth-century literati and savants whose correspondence you can now read on an Oxford University website called Electronic Enlightenment.

This republic of letters might further be characterized as the Widest West. Its core undoubtedly remains in North America and Europe. Indeed, despite several brave European attempts to create a pan-European intellectual review, The New York Review is the closest thing we Europeans have had to a European Review of Books. But our republic also extends to the whole English-speaking world, Latin America, and South Africa—and to wherever, be it in India, Burma, Egypt, or China, there are writers and readers who share the basic values of this modernized version of the Enlightenment.

These are, I claim, recurrent features of a certain basic approach to a recurrent set of political problems. Not only can I point you to examples from each decade: these echo and speak so loudly to each other that, turning the pages, you involuntarily exclaim “plus ça change….” Read Hannah Arendt’s “Lying in Politics: Reflections on the Pentagon Papers” and you are reading about Edward Snowden and the NSA. Jump aboard Mary McCarthy’s 1967 report on the US military in Vietnam, and you are transported to Afghanistan in 2007. In a piece about American politics published in the autumn of 1963, David Riesman evokes “the fantastic traffic jam of American political institutions, vested interests, ideologies, paranoias, and ‘don’t fence me in’ chauvinism.” What a perfect description of Washington in this autumn of 2013: The Fantastic Traffic Jam.

Yet beside continuity there is always change. We see time’s cycle, but also time’s arrow. Our story begins in Camelot. The Review emerges in the full, glorious glow of the John F. Kennedy presidency. 1963 is the year of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” and of Kennedy’s “Ich bin ein Berliner” (phonetically written down as “Ish bin ein Bearleener”). The United States, this president has promised the world, will “pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” Insiders knew then, and we know even better now, how far the reality of Camelot fell short of the Arthurian dream. (There’s a gloriously savage 1965 Review essay by Malcolm Muggeridge about the “pile of Kennedyana” he has just “pushed aside…with mounting distaste.”) And yes, that year descends into darkness with the bombing that takes the lives of four innocent young black girls in Birmingham, Alabama, and the assassination of JFK.

Advertisement

Yet there is no doubt that this was a time of extraordinary promise for a certain vision of a better America at the heart of a better world, one accompanied by a persuasive reality of American military, economic, cultural, and scientific power. (“Oh, and by the way, we’re going to put a man on the moon.”) That promise was believed by millions around the globe. As I noted in the 1980s, Martin Luther King was a much more direct inspiration for the German Green politician Petra Kelly than Martin Luther. The Review reinforced at home and magnified abroad the attraction of that modernized Enlightenment vision, not least because it was so critical of the United States’ repeated failure to live up to its own proclaimed ideals (which was my point about Central America in 1984).

Now let me risk a perhaps suicidally broad generalization. With the benefit of hindsight, we can say that across nearly forty years, until the turn of the century, America and the world moved closer to, rather than away from, that vision. At home, in the United States, more people—of different color, gender, sexual orientation—came to be treated, at least in law and policy, as deserving of full, equal liberty and dignity. Abroad, more peoples become more free: in southern Europe (Greece, Spain, Portugal), in South America, in the former Eastern Europe during that year of wonders 1989, in South Africa—where Nelson Mandela, imprisoned following the “Rivonia” trial that opened in the founding year of the Review, became president in 1994.

Compare and contrast the forty years between 1913 and 1953. For much of that period, Europe was—as the historian Mark Mazower has aptly called it—a “dark continent,” one in which tens of millions of human beings were murdered, tortured, and oppressed in previously unimagined ways. Worldwide, it was not at all clear that liberal democracy would win the three-way ideological fight with communism and fascism. For much of that time, and in many places, communism and fascism seemed to be winning. Meanwhile, a large proportion of humankind continued to labor under colonial yokes of one design or another. By comparison, and measured against the values we citizens of this liberal republic of letters embrace, who would not describe the years between 1963 and somewhere around 2000 as decades of progress?

To be sure, we must beware what Henri Bergson called the illusions of retrospective determinism: the seductive belief that what actually happened in history somehow had to happen that way. History does not move in straight lines. Nothing was inevitable. There were huge setbacks along the way, from the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 to Watergate, from Vietnam to Bosnia and Rwanda. Vast slow-moving horrors were left to unfold, including those of mass poverty, pollution, and waste, and many an individual moral monster went unpunished. Nonetheless, at the turn of the twentieth to the twenty-first century, a liberal internationalist citizen of our literary republic could feel encouraged by the recent past, and hopeful about the future. If you were not careful, you might even succumb to a Whig interpretation of history.

How different that world looks today, as we see it illuminated by the same, steadily rotating lighthouse beam—and how very much less encouraging, measured against the values we believe in. I would highlight three main reasons for this reverse. The first is the post–cold war hubris of the United States. Remember the “hyperpower”? The “unipolar world”? That hubris was followed, as hubris tends to be, by nemesis: nemesis abroad, in the disaster of the Iraq war, and nemesis at home, in the financial crisis and its manifold consequences. For any friend of the United States, it has been excruciating to observe this great country inflict such extensive, needless damage on itself.

Second, there is the condition of the Islamic and especially of the Arab world. In 2001, its brutal fanatics successfully provoked the Bush administration into tipping the United States over the brink, from hubris to nemesis. Equally depressing is the fate of the Arab Spring. In 2011, on the streets of Tunis and Cairo, liberal internationalist hopes were raised again. Were not these manifestations of civil resistance at the heart of the Arab world in their own way another 1989? Looking at most of the results in that region today, it seems hard to respond with anything but an emphatic “no!”

Most important is the rise of China, which appears—at least for now—to have successfully decoupled the dynamism of capitalism, in the globalized economy Karl Marx once predicted, from liberal democracy and respect for human rights. We have no idea how long the fantastic centaur of Leninist capitalism will endure. The leaders and insiders of the Chinese Communist Party seem to understand better than many Western observers just how fragile their system is. That is one reason the new administration of President Xi Jinping is tightening the screws not just on outright dissent but even on discussion of allegedly subversive Western ideas such as constitutionalism. A deep political crisis at some point over the next five to ten years seems to me ever more likely. Yet only an incurable liberal optimist would predict that the outcome of that crisis, at least in the short to medium term, will be a transition to more or less liberal democracy, as seen in Eastern Europe, South Africa, and much of Latin America.

We therefore have to distinguish between admiration for the moral courage and intellectual clarity of dissidents in China and the Islamic world, and an informed judgment on the chances that they will triumph politically—not just morally and intellectually, which they have already—as did Havel, Solzhenitsyn, Sakharov, Michnik, Mandela, Aung San Suu Kyi, and others to whom the Review has given such an honored place. (Havel made thirty-seven contributions to these pages, Sakharov ten.) Perhaps they will. After all, it took nearly thirty years for Mandela, and more than twenty for Aung San Suu Kyi. But we cannot count on it. We must also be prepared for other outcomes, and to understand what causes them.

Meanwhile, the balance of economic power continues to move away from the West. There is an amusing little exercise by the McKinsey Global Institute that maps the journey of the world’s “economic center of gravity.”2 For centuries, that imaginary center hovers somewhere above today’s Pakistan, balanced between Europe and China. Sometime around 1820 it starts marching rapidly westward, reaching Germany in 1913 and getting close to the east coast of North America by 1950. From 1960 to 2000 it wanders slowly eastward across the seas between North America and Europe—that is, to put it another way, across the intellectual and political mare nostrum of the Review. From 2000 to 2010, however, it shoots sharply toward China, landing in 2010 in the vicinity of Nadym, in northern Siberia. By 2025, the McKinseyists predict that this global “economic center of gravity” will be back somewhere north-northeast of where it was in 1820, perhaps in the neighborhood of Novosibirsk. This is a game, of course, and predictions are just predictions, but I would bet that the center of economic power is not heading back westward anytime soon.

Political power is shifting too, at remarkable speed. China’s influence in Africa and Latin America is already large. The United States may remain the “indispensable nation,” but as we have seen in the Middle East this year, its ability to get things done on its own, or just with the help of its European allies, has diminished, is diminishing, and will probably continue to diminish. Instead, we have the Gogolesque spectacle of President Vladimir Putin using the Op-Ed page of The New York Times to lecture President Obama on the importance of respect for the rule of law and the fact that all states are equal in the eyes of the Lord.

We have traveled a long way from Camelot. Some call this a “post-American” or a “post-Western” world. The shorthand is useful, but can also mislead. Clearly, it is not post-American or post-Western in the sense in which we might say, for example, post-Soviet, post-Thatcher, or post-Saddam. The core geopolitical West, comprising Europe, the United States, and other states of the Anglosphere, remains the biggest military, economic, and cultural power in world affairs, if and when it acts together. But as others rise, its relative power has declined, and this, along with its own internal divisions, reduces its ability to set the agenda of world politics.

For our republic of letters there is another centennial, if not millennial, transition that becomes especially relevant at this point in my argument. As a label for this transition, the shorthand corresponding to “post-Western” is “post-Gutenberg.” This does not mean that printed publications cease to exist. However, the transition to digital, online, virtual—choose your preferred term—is happening even faster than the power shift from West to East. It also reaches backward in time. As I brooded in the sun-drenched Californian hills above Stanford University on how to approach this essay, I decided that I would look through copies of the Review for one year in every ten (1963, 1973, 1983, etc). But the Stanford University library no longer has print copies from earlier years. Only with great difficulty did a noble librarian secure, on interlibrary loan, some old bound volumes that other American universities had not yet digitized away.

I am enough of what Marshal McLuhan once called “Gutenberg Man” to feel that something is lost here. I don’t just mean the smell of old newsprint. I mean the serendipity of page-turning and diagonal browsing, as one does to such advantage when reading a well-edited print broadsheet. There are also those small details that the diagonal eye of Gutenberg Man chances upon, such as the many book ads in the Review, including, for example, a life of De Gaulle allegedly “Banned in France” and The Joy of Sex. (“THE JOY OF SEX is different with a Capital D.”) Then there’s the changing language of the Review’s famously outré personal ads. (“Caucasian bachelor, educator, 33…seeks attractive, liberal-minded Oriental girl, 23–30, San Francisco area….” Caucasian! Oriental! This was 1973.) Even if it’s all there somewhere in the online archive, you are less likely to chance upon it by virtual page-scrolling.

Yet the digital opportunity for our republic is far larger than any marginal loss. The digital revolution confronts daily newspapers with an existential question: How can a quality supply of general and especially of foreign news be maintained if most people expect not to have to pay for it online? (An ironic new version of the Guardian editor C.P. Scott’s famous dictum that “comment is free, but facts are sacred” is: “Comment is free, but facts are expensive.”) The same question mark does not hang over good magazines, which are ideally suited to being read on a tablet or other handheld device. Students who have never in their life purchased a daily newspaper will pay for a magazine app. Moreover, the transition to online gives a tremendous new freedom, not least from the space and form constraints of print. Put very simply: you can run longer pieces, shorter pieces (aka blog posts), and more pieces, as well as podcasts, photos, and videos.

This digital freedom has more than just technological and commercial implications. It opens cultural, intellectual, and political possibilities as well. If it is true that the affairs of the world will increasingly be shaped, over the coming decades, by countries that would traditionally be considered non-Western, then it is vital that we understand more of what political intellectuals in those countries are thinking and writing. Marx’s “the ruling ideas are the ideas of the rulers” is crude determinism, but there is certainly some connection between prevailing political power and intellectual influence. There is therefore a pressing political reason, next to pure intellectual curiosity (which should be sufficient reason in itself), to broaden the conversation, extending and opening still farther the frontiers of our republic.

Online possibilities make this easier, but so does another circumstance. It would not be unreasonable to assume that a substantial percentage of the citizens of our New York Review republic, both writers and readers, either work at or are in some way connected with English-speaking universities. Those universities happen also to have educated, and—as a glance into any graduate seminar room at Oxford or Stanford will immediately confirm—continue to educate, in growing numbers, a significant and potentially influential minority of the elites of other countries, including those of emerging powers such as China, India, and Brazil. This does not merely give us and them a common language and set of concepts for talking about our differences. It also means that there is a genuine mixing of cultural, intellectual, and political influences in each person—so that few, if any, leading writers and thinkers are now purely and exclusively Chinese, Indian, Islamic, or whatever.

I once asked a friend at Peking University (as it still calls itself in English), himself a cautiously liberal historian of political thought, why the politics of a Chinese mutual acquaintance, a New Left thinker—let us call him Y—who at that time enthusiastically supported Bo Xilai’s so-called Chongqing model, were so different from his own. I expected a reply referring to Chinese history, politics, or life experience. “Well,” said my friend, “the thing is, you see, while we were both at the University of Chicago, I did my doctorate with Edward Shils at the Committee on Social Thought…but Y was in Political Science!”

Yet these thinkers also remain profoundly shaped by their own cultural and intellectual traditions, and often revert more strongly to them after some years back home. So this has to be a two-way, or more accurately a multidirectional conversation, as we continue to strive toward a more universal universalism. Never ceasing to explore what it means to sustain equal respect and concern for every individual’s freedom and dignity, we must remain true to the core values of a modernized Enlightenment liberalism, Western in origin but universal in aspiration. And we must continue to offer a special platform to the persecuted and censored individuals in less free countries who largely share these values, even if—perhaps especially if—their chances of political success there are small. But we must also be able to hear, to listen to, and to engage with those different voices from other traditions, which may prevail politically for some considerable time to come. There is no better place to do this than our now digital republic.

This Issue

November 7, 2013

Love in the Gardens

Gambling with Civilization

On Reading Proust

-

1

“Back Yards,” The New York Review, November 22, 1984. ↩

-

2

See Richard Dobbs and others, “Urban World: Cities and the Rise of the Consuming Class,” McKinsey.com/Insights, June 2012. ↩