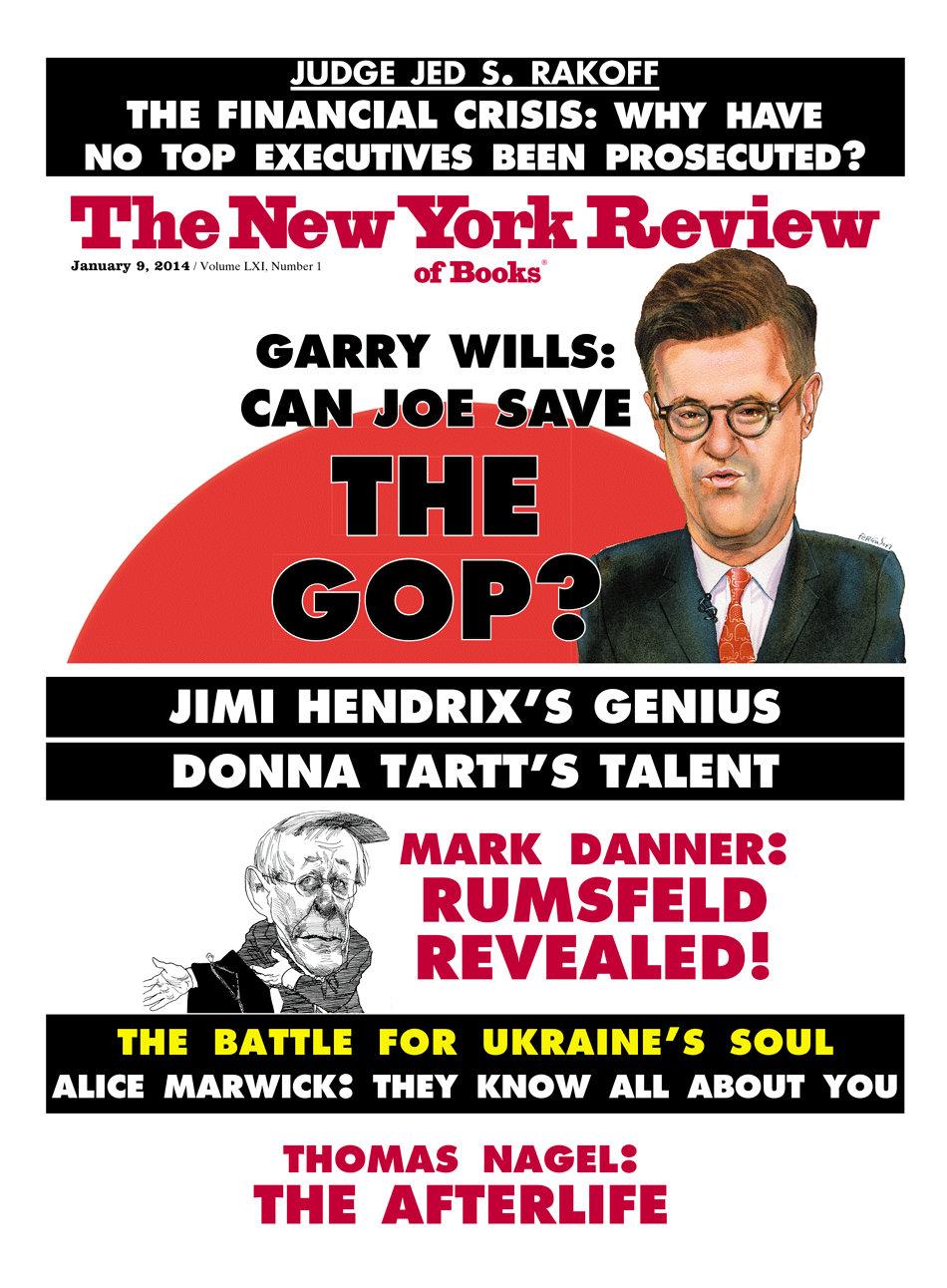

Tim Parks has never been a man to take any received wisdoms for granted, however blameless they might appear. Perhaps his best-known novel, the Booker-shortlisted Europa (1997), had the regular refrain “every man is an island,” as the academic narrator Jerry Marlow gave everything from the environmental movement to the concept of universal human rights a thorough and often withering examination. Along the way, he also served up some surprisingly heartfelt paragraphs on the inadvisability of seizing the day and the wisdom of crying over spilled milk.

As for books, Jerry reserved especial scorn for writers “who do nothing more than analyse the world in a way in which it has grown used to being analysed”—a view certainly shared by his creator. Parks’s own critical writings, many of them for this magazine, display a similarly high-minded rigor that has enabled him, for example, to dismiss Salman Rushdie as something of a lightweight crowd-pleaser. More heretically still, last year he wrote a disturbingly persuasive blog post arguing that the Kindle offers a more austere and therefore grown-up literary experience than those gaudy, self-congratulatory objects known as books.

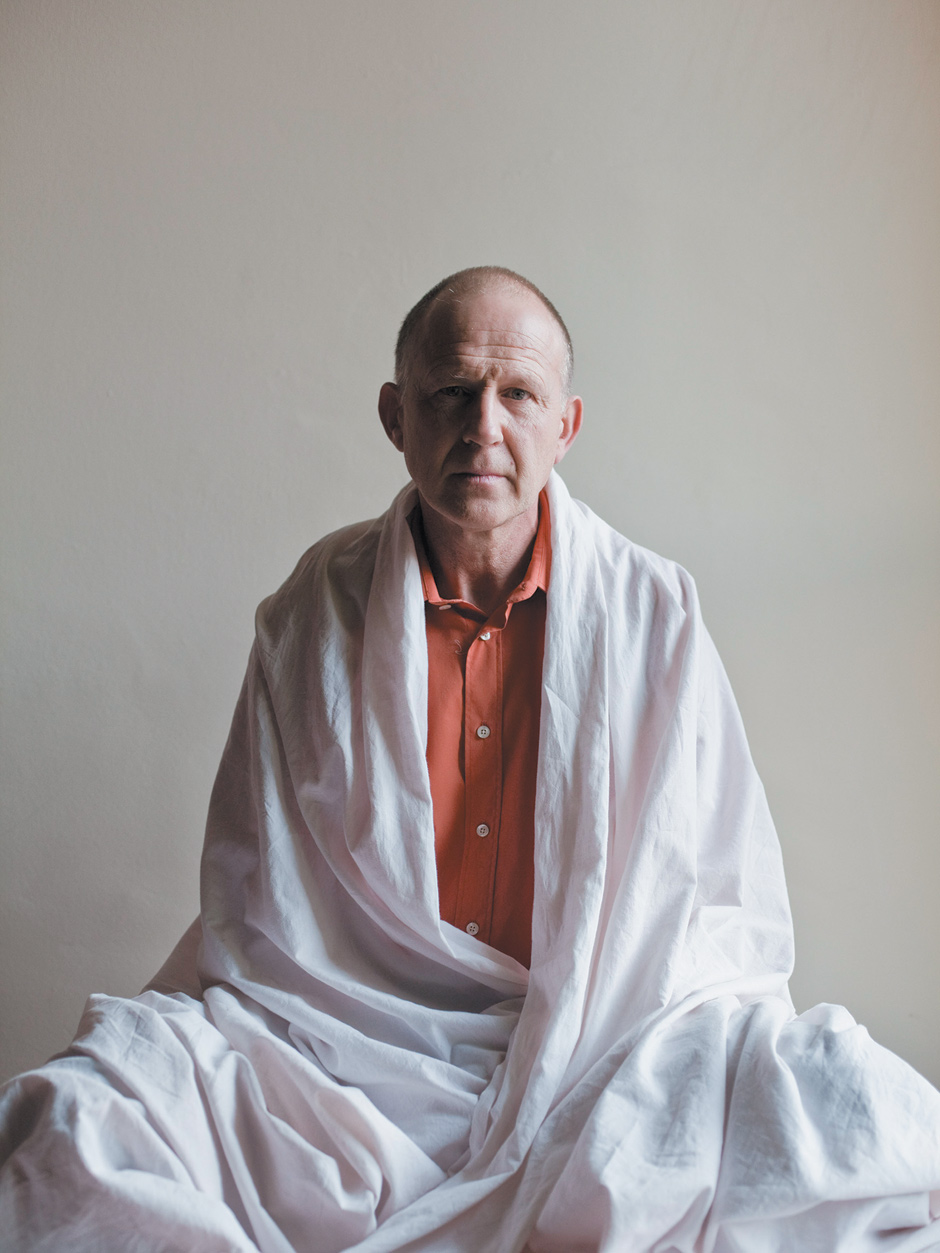

Despite this track record, though, the last gaudy object he published must have come as a shock to even the most seasoned Parks reader. In the nonfictional Teach Us to Sit Still, this apparently sternest of rationalists provided a sincere, touching, and only occasionally sheepish celebration of the transforming power of Vipassana Buddhist meditation. Parks may have turned to the practice only after all the more orthodox attempts to cure—or indeed diagnose—his chronic pelvic pain had failed. Nonetheless, by the end of the book he was writing unblushingly about “life’s journey” and how “if you stay focused” during meditation, “the entire body links up and ignites…. Whirling orbits of bright electrons, pure energy, without substance.” You can, in short, learn to “open your heart”—words, he acknowledges, that “normally make me cringe.”

To understand the scale of this conversion, you could pick up almost any of Parks’s earlier works, fiction or nonfiction, where it wouldn’t take long to spot one of his long-standing themes: in a world full of illusions, the idea that you can change your life is one of the most persistent and least intellectually defensible. In book after book, we’re plunged deep into the heads of erudite middle-aged men in crisis—marital, parental, professional, or more usually all three. These heads then buzz with contradictions as their owners try to overcome both their crises and “the burden” of the self, before being forced to realize that they’re stuck with them. This, in fact, is nothing short of our “destiny,” a word that Parks has used as the title of a 1998 essay, a 1999 novel, and throughout his career to mean, among other things, “the mistakes [we were] made to make,” the person we unaccountably find ourselves married to, or simply “the ultimate and unavoidable imposition…of being oneself.” As the narrator of his novel Goodness put it more than twenty years ago, “people are who they are and forever remain so…. Just as it is destiny to be black, destiny to be white. This is what self means, surely. Otherwise who are we?”

The bad news in these books, then, is that the only way your life could be different is if you were someone else. The best the average Parks hero could hope for was to achieve “catharsis through exhaustion,” where battling against the unshakable realities of the world and the self becomes just too tiring to carry on with, leading to a kind of acceptance that’s not always easy to distinguish from, say, completely giving up.

Teach Us to Sit Still suggested that to the list of Tim Parks protagonists who’ve experienced such a catharsis could now be added the name of Tim Parks. In his belief that a novelist should invariably prize truth over comfort, Parks once wrote with a mixture of pride, defiance, and mild regret that “the writer has thus attached his identity to a process which cannot bring serenity.” Now, he seemed to feel that a bit of serenity might not be so bad, even if it meant abandoning writing altogether: “With the writing behind me, the tussle in the mind would be over…. All over. My health could only improve.”

Needless to say, Parks was aware of the irony of using writing to talk about giving up writing. Even so, his change of heart did sound alarmingly convincing. “In the end,” he wrote, echoing the many Parks characters who’d reached the same exhausted conclusion, “I no longer believe that it is given to us to understand why we behave as we do. I should stop trying.”

All of which makes the appearance of a new Parks novel particularly intriguing. Clearly, he hasn’t stopped trying after all—but as we soon discover, nor has he quite resumed business as usual. On his website, Parks describes Sex Is Forbidden as a “companion novel” to Teach Us to Sit Still. In fact, it feels more like a response, both thoughtful and uncertain, to the various challenges that meditation poses to his work as a novelist, including the question of whether they can be combined at all.

Advertisement

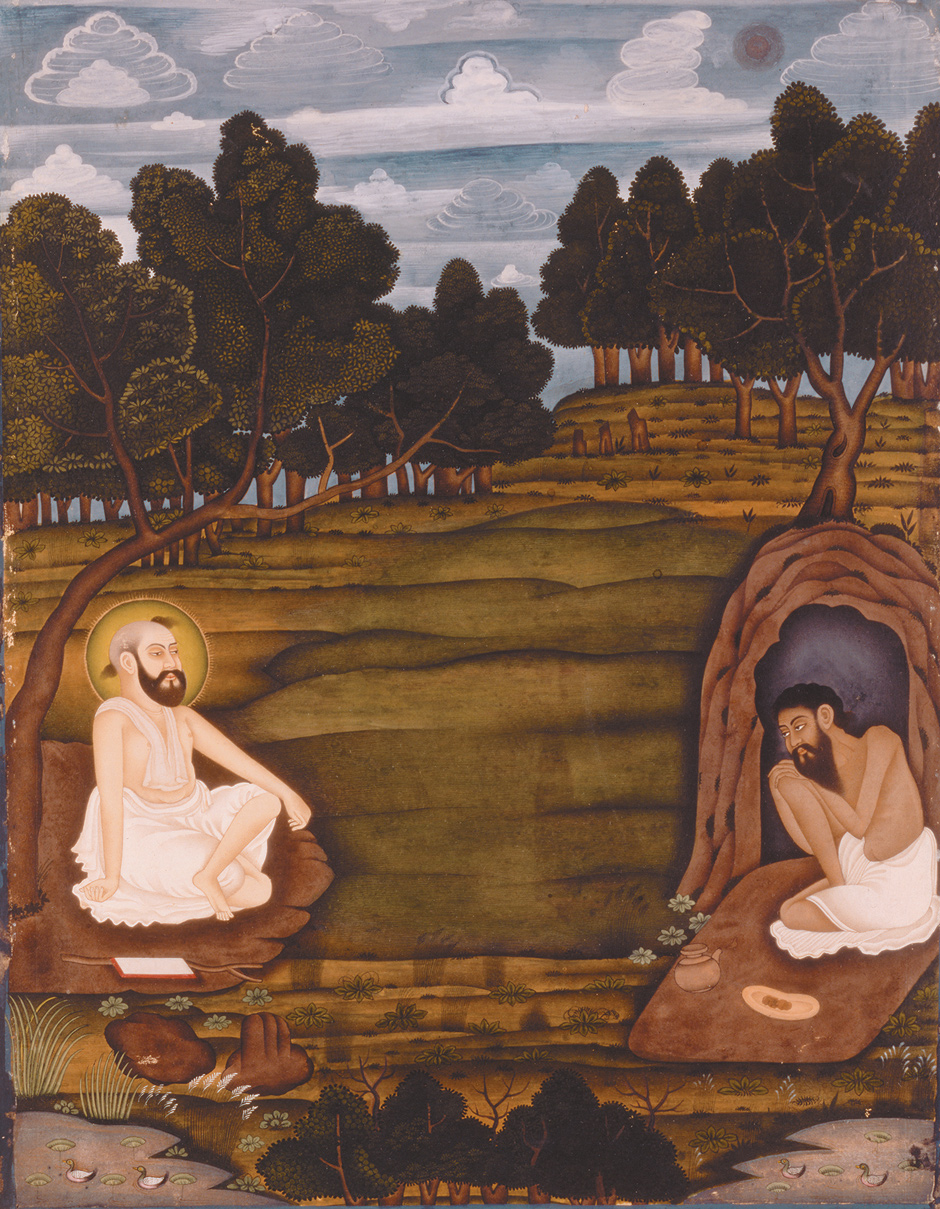

Most notably, the book is set on a silent Buddhist retreat where not only is sex forbidden, but so is more or less everything else that has been the stuff of Parks’s fiction (and of most other people’s too). In meditation—and the book has plenty of it—there is “no story, no rhetoric, no deceit.” Instead, the aim is to go beyond words, thoughts, and cravings to achieve the sort of equanimity that his previous novels have so bracingly written off as impossible. In this, the key is to rid yourself of sankharas, defined as “painful formations of the mind”—and if there’s a pithier summary of Parks’s subject matter over the past twenty-nine years, it’s difficult to imagine what it might be.

In Teach Us to Sit Still, despite his anti-writing vows, he admitted at one point that “of course I then imagined writing about this…and how brilliantly I could deconstruct myself, or someone like me (very like me), in a novel perhaps.” In Sex Is Forbidden he goes a step further: by deconstructing the possibility of such a deconstruction. Inevitably, this means that even by Parks’s standards we’re in for an exhilaratingly knotty read.

For one thing, it’s not obvious who the main character is. At first sight—and several subsequent ones—it would appear to be the narrator Beth Marriot, a young woman who’s been working as a “server” in the Dasgupta Institute near London for the past eight months, cleaning the rooms and preparing the food for the people on retreat. Although writing is yet another of the institute’s prohibitions, Beth starts to keep a record of a single ten-day retreat, detailing her experiences of meditation, providing sharp pen-portraits of her fellow servers (who are allowed to speak to each other), and gradually revealing the traumas that led her there in the first place.

The sexy lead singer of a small-time rock band, Beth had been guiltily in love with Jonathan, a married fifty-two-year-old painter, and guiltily not in love with her much nicer boyfriend Carl. Pregnant by Jonathan, and on a French vacation with Carl, she was indulging in her favorite habits of drinking, taking drugs, and flirting with strangers when she went skinny-dipping in a rough sea. As a result, she lost the baby and caused the death of the smitten French boy who dived in to save her.

Beth shares the taste for contradiction traditionally shown by Parks’s narrators (“Every time I feel something I feel the opposite”). Yet a rock chick with little knowledge of books (“Jonathan read all those miserable books. Cormac something. Thomas Bernstein?”) does initially seem to indicate that Parks has abandoned the idea of fictionalizing his own concerns and is heading into new territory. But as it turns out, any of his readers missing a full blast of authentic middle-aged male angst will not have to wait long.

When the novel opens, Beth is doing a good job of putting the past behind her. Until, that is, she comes across the diary of one of the retreatants and takes it away for an illicit peek—at which point her role as a Parks character is increasingly combined with that of a Parks reader, or maybe reviewer. That’s because the diary, of which we get several long and troubled extracts, is being kept by a man who seems deliberately intended as an archetypal, even slightly parodic, Parks protagonist. So deliberately, in fact, that it’s hard not to think that the diary represents a version of the original deconstruction Parks had in mind.

Like many a Parks protagonist before him, Geoff Hall has a determinedly English name (previous examples include Morris Duckworth, Roger Cruikshank, George Crawley, and Christopher Burton). He also has a failing business as a publisher; a wife he doesn’t like, but regards with “a sense of destiny”; a mistress he’s lost by not leaving his wife soon enough; and a daughter going off the rails. Above all, he’s stuck with the same thoughts “turning round and round”—and, rather than being merely exhausted, is “exhausted exhausted exhausted exhausted exhausted exhausted EXHAUSTED.” From Teach Us to Sit Still, we know too that Geoff shares several characteristics with Parks himself (or someone very like him): chronic pain, a stooped posture, slanted handwriting, a skepticism about Buddhism’s obsession with numbers, as well as moments of meditation that are genuinely transforming and at one stage cause a bout of epiphanic weeping.

Advertisement

Even before she discovers whose diary she’s reading (and he discovers that she’s reading it), Beth senses a fellow spirit—and not just because she sympathizes with his sexual dilemmas, father-daughter problems, and amused awareness of the competitiveness that accompanies Western attempts at meditation. The cliché that we are “a story-telling species” is one that Parks has long subjected to his usual fierce scrutiny, and here Geoff and Beth both share his belief that this is not necessarily good for us. “I am locked in a story and can’t wish it away,” writes Geoff. “Your story becomes [who] you [are],” laments Beth.

Where they do part company is once Beth’s role as reviewer takes off, because her comments on Geoff’s diary can be as damning as anything in Parks’s own critical writing. “Flicking through the pages,” she tells us, “it doesn’t seem to matter where you start. He hammers on like a drum solo at a druggy festival.” Faced with Geoff’s classic Parksian riff about not wanting to feel superior all the time (“Actually, I’m already thinking how superior I am, wanting not to feel superior. And how superior of me to have recognized this paradox”), she’s even harsher. “What a prick!” she observes.

Her overall verdict on “this old guy’s guff,” however, is more nuanced. The real problem, she decides, is that “the bloke is awesomely attached to being who he is…. I hadn’t hung around failing rock musicians for years without seeing how they all adored the drama of their frustrations.” When the retreat ends and Beth and Geoff can finally talk, the “reader’s report” that he directly asks for is summarized by the sentence, “You love your pain too much, Mr Diarist.”

But if this makes Beth sound more like a device than a character, that wouldn’t be fair. She is, as she remembers Carl telling her, “bursting with life,” and Parks pays at least as much attention to her struggles as to Geoff’s. Still, it does seem clear that part of her purpose is to bring a fresh pair of eyes to the debate about where Parks’s writing now stands after his discovery of meditation: whether wordless truths can ever be caught in words and, if they can’t, how and whether he should carry on. (“Stop writing, Mr Wordy Diarist,” Beth says to Geoff in her own notebook at one point. “Stop writing about yourself…. If you were really suffering you’d prefer these pages to stay white.”)

Admittedly, in order to perform this role, Beth does sometimes show an unusual level of philosophical wisdom for her years. She’s also unexpectedly attuned to the problems of the middle-aged male meditator, mental and physical: “I bet their thighs and ankles burn like hell through the sittings.” It’s a problem that has obviously crossed Parks’s mind, although his efforts to counter it aren’t entirely successful. “Girls get through their shit younger, I suppose,” Beth blithely notes near the beginning. “How can she be so young and so wise?” Geoff asks himself later on, but without attempting an answer.

Feminist readers, meanwhile, might wonder whether a woman of her age would spend quite so much time describing her own breasts—organs that Parks himself has rarely left undescribed in his previous work—or proudly recalling the many compliments they’ve been paid.* They might wonder, too, whether she’d respond to an accidental sighting of fiftysomething Geoff in his underpants with quite such enthusiasm: “The skin was smooth and the pack between his legs plump and solid. I gave it a little pat.” Non-Buddhists should be warned that Parks doesn’t stint on the technical terminology: “I wanted jhāna to make me new…. I have experienced anicca…. I haven’t achieved paññā, let alone nibbana,” writes Beth in the space of one paragraph.

Taken as a whole, though, Sex Is Forbidden definitely and triumphantly fulfills Parks’s criterion that the best novels don’t analyze the world in a way in which it’s grown used to being analyzed—which is why the result manages to be fascinating, fearless, and distinctly odd. It may also be why even its publishers don’t seem to know what to make of it; they quote a review optimistically describing it as “a fast-paced comic novel,” a phrase in which only the word “novel” feels accurate. More appropriate would have been the quotation from Schopenhauer that Parks used in his demolition job on Salman Rushdie: “The art [of the novel] lies in setting the inner life into the most violent motion with the smallest possible expenditure of outer life”—although you can understand why the sales department might have vetoed that.

Given that much of this violent motion appears to be happening offstage, in the inner life of the author, it’s not easy to say what a Parks novice would make of the book either. Nevertheless, for anybody who’s followed one of the more idiosyncratic, underrated, and at times distinctly cussed literary careers of recent times, Sex Is Forbidden is a welcome chance to receive the latest bulletin from Parks’s ever-stimulating and ever-restless mind.

In this reading of the book, the painter Jonathan has an important walk-on role. By his own account, Jonathan is “famous in a manner of speaking”—which is to say, not as famous as he’d like. And Parks has made no secret of the fact that this is his situation too. According to his own characteristically clear-eyed assessment, in America he’s best known as a literary critic; in his once-native Britain as somebody who writes amusingly about Italy, where he’s lived since 1981; and only in continental Europe for his more serious novels. Yet he still hasn’t had the full recognition that part of him craves and (rightly) thinks he deserves.

On the other hand—and here’s the cussed bit—he doesn’t want to succeed simply by giving people what they want: “For real recognition involves the reader’s wholehearted endorsement of my, truly my vision. Not his consumption of something he already knew he wanted. What god would ever pander to the way man saw things?” (As Martin Amis once put it, all writers want, and expect, “the reverence due, say, to the Warrior Christ an hour before Armageddon.”)

Bearing that in mind, one conversation in particular that Beth remembers having with Jonathan is surely significant. He has, he tells her, always put his work first:

“Was it worth it?” I asked.

He thought quite a while about that. What I loved about Jonathan was that he really did think about things when you asked a tough question. He did try to tell you the truth, even if it wasn’t the truth you wanted to hear. “Yes and no,” he finally said…. “I have this studio…. I paint. Well enough. Pretty well, actually. And from time to time I sell something. From time to time…. I have the price of a taxi when I need one, the price of a restaurant…. But no, I haven’t changed the history of painting. No, I’m not on everyone’s lips.”

“Who cares?” I snuggled up to him.

“I do,” he said at once. He didn’t have to think about that. “But the question isn’t really, was it worth it, the question is, could I have done otherwise? And the answer there is, I don’t think so. It’s impossible to be categorical…but I really don’t think so.”

And in the end, if such a slippery and teasing novel can be reduced to a single conclusion, then this is it: that like all those characters of his who’ve been forced to realize they’re stuck with their wives/mistakes/painful formations of the mind, so Parks himself is stuck with writing. The fact that it appears to be his destiny is certainly cheering news for readers. Judging from Sex Is Forbidden, though, it’s a more ambiguous prospect for Tim Parks.

-

*

Funnily enough, one of those compliments, “You’re a giggle of tits, Betsy M, Jonathan said,” is also paid by the eponymous Roger—“A giggle of tits, I would describe it”—in Loving Roger (1986), Parks’s second novel and his only other with a female narrator. ↩