In response to:

Good Unclean Fun from the December 5, 2013 issue

To the Editors:

Having written the introduction to Nathaniel Dubin’s translations of the The Fabliaux, I respond to Christopher Ricks’s characterization of the medieval works as misogynist bad poetry [NYR, December 5, 2013].

While the comic tales repeatedly denounce the “wiles” of women, they poke even more fun at male peasants, priests, and knights. And in most fabliaux, women come out on top. “The Good Woman of Orleans” is the story of a husband who tries to entrap his wife by returning home early in disguise. The clever wife recognizes the ruse, has him locked in a room while she entertains her lover between the sheets, then orders the servants to beat the disguised intruder, who ends up atop a manure pile, delighted at his wife’s apparent fidelity.

A fine reader of poetry, Christopher Ricks admits to not reading the original Old French, which makes his purchase upon Dubin’s renderings approximate at best. Dubin’s English equivalents are as good as translations get. He reproduces the world and the feeling of the medieval tale, and finds linguistically and culturally resonant equivalents for words and things, deeds and patterns of thought. In “The Blacksmith of Creil,” Dubin captures all the medieval poet’s naughty reveling in the apprentice’s epically proportioned “well-sharpened tool”:

God’s honest truth, one shaped so fair

that Nature must have lavished care

to make it, and surpassed her craft:

around the bottom of the shaft

two palms in length, wide as a fist.

A hole, though shaped like an ellipse,

in which this well-hung stud had placed it

would look as if a compass traced it,

so very round would it become.

About his balls I’ll not keep mum,

hanging between his ass and pizzle

like mallets sculpted with a chisel.

Dubin’s felicitous phrase, which sums up the medieval topos of Natura Creatrix, is an instance of genius in translation: “The blacksmith goes right on repeating/the young man’s praises, waxes lyric/in superphallic panegyric.”

The fabliaux belong to a low genre. Their extended singsong rhymes and jaunty rhythms, sometimes spanning five hundred lines, make them more the equivalent of rap than of the limericks to which Ricks compares them. Unlike the idealistic Old French epic or courtly romance, they offer an unsurpassed window upon the habits of the common people of the High Middle Ages. They are the stuff of pure enjoyment, and a royal road to inhabiting realms and selves distant from our own.

Howard Bloch

Sterling Professor of French

Yale University

New Haven, Connecticut

This Issue

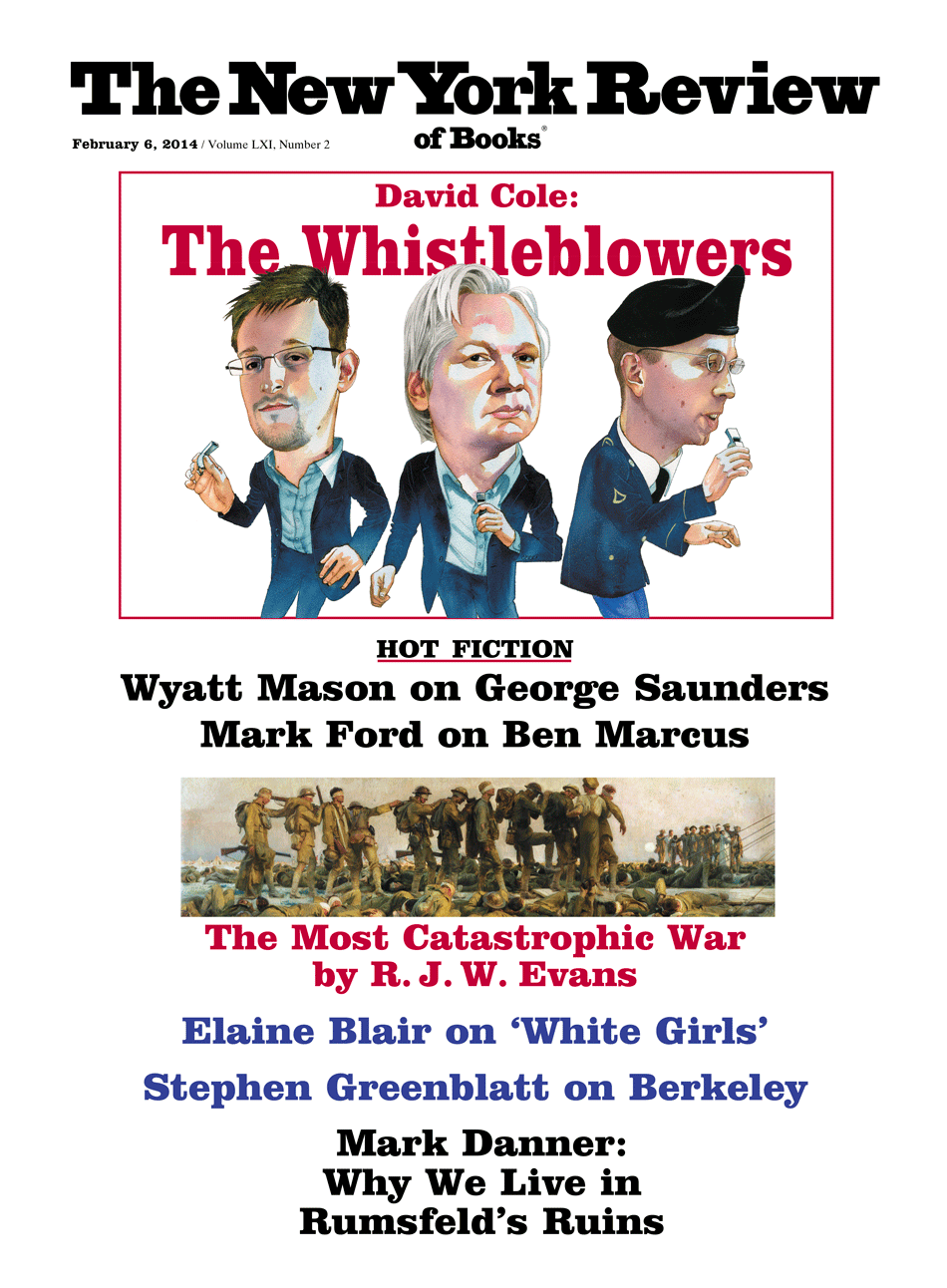

February 6, 2014

The Whistleblowers

The Most Catastrophic War

On Breaking One’s Neck