Elizabeth Warren has quite a story to tell. For many years, she was a professor at Harvard Law School. Inside the worlds of academia and Washington policymaking, she was known for her research into the causes and effects of bankruptcy, and for her ultimately futile campaign to block a Republican-driven effort to rewrite the bankruptcy law in favor of big banks and other lenders. Until the 2008 financial crisis, however, Warren was largely unknown to the American public. Then, following the subprime mortgage meltdown, she emerged as a vocal and stinging critic of Wall Street and its political enablers.

Today, at the age of sixty-four, Warren holds Ted Kennedy’s seat in the Senate. She’s perhaps the most recognizable leader of what has been called a resurgent progressive movement, and some of her supporters are urging her to jump into the 2016 presidential race. During the last few months, she has repeatedly said she’s not running. But that hasn’t put an end to the speculation about her future, and neither will the publication of her new memoir, A Fighting Chance, which reads a lot like a campaign autobiography.

The book combines a revealing account of Warren’s rise to prominence with prosaic personal details—lots of hugging babies and dogs—and ringing political declarations. Its begins: “I’m Elizabeth Warren. I’m a wife, a mother, and a grandmother.” And it goes on:

I never expected to go to Washington. Heck, for the most part I never even wanted to go. But I’m here to fight for something that I believe is worth absolutely everything: to give each one of our kids a fighting chance to build a future full of promise and discovery.

Two hundred and seventy pages later, in an epilogue, Warren returns to the pugilistic theme, although, in truth, she never really departs from it: “I believe in us. I believe in what we can do together, in what we will do together. All we need is a fighting chance.”

Does that sound like somebody who has definitively ruled out a tilt for the Oval Office? If A Fighting Chance doesn’t settle what Warren will do next, it does help answer a number of questions that her political success has brought to the fore. Who is Elizabeth Warren? What does she represent? Does she have plausible solutions to the nation’s problems?

Even if Warren doesn’t run for president, she is a significant figure, and her arguments demand to be taken seriously. When she declares, “Today the game is rigged—rigged to work for those who have money and power,” she is reflecting the beliefs of countless Americans, many of whom don’t share her progressive outlook, but do share her scathing views of the Wall Street–Washington nexus.

From the moderate wing of the Democratic Party, one occasionally hears complaints that Warren is a rabble-rouser who deliberately oversimplifies things. But who could honestly challenge her description of the American polity? According to a recent report, more than half of the members of Congress are millionaires.* During the 2012 presidential election, the Federal Election Commission says, more than $7 billion was spent. And following its 2010 decision in the Citizens United case, the Supreme Court, on April 2 of this year, struck down some of the few remaining limits on campaign contributions. In the words of the civil rights activist Clara Luper, “Money doesn’t talk, it screams.”

Elizabeth Anne Herring was born on June 22, 1949. She grew up in and around Oklahoma City, a midsized city located in the center of the state, an area subjected to lengthy droughts and occasional tornadoes. Her father, Donald, whose family owned a store, “had big dreams,” Warren writes. “He wanted to fly airplanes.” After leaving school, he taught himself to fly a small plane.

During World War II, he became a military flight instructor, but his hopes of becoming an airline pilot were frustrated. After the war, he took a variety of jobs, including running a car dealership and selling carpets and other items at Montgomery Ward. He struggled to earn enough to support his beloved “Betsy,” her three older brothers, and his wife, Pauline, a woman who, according to family lore, had Cherokee forebears. To the horror of his parents, he had eloped with her at the age of twenty. “Like a zillion other families, we got by,” Warren tells us. Eventually, her father got a permanent job as a janitor. Her mother also went out to work, answering the phones at Sears. But money remained in short supply.

Attending a local high school, Warren did well enough in class, but with her thick glasses and her social anxieties about her family’s straitened circumstances, she didn’t have much fun. In fact, she says, “I hated high school.” Except for being on the debate team, that is:

Advertisement

The way I looked at it, I wasn’t pretty and I didn’t have the highest grades in my school. I didn’t play a sport, couldn’t sing, and didn’t play a musical instrument. But I did have one talent. I could fight—not with my fists, but with my words. I was the anchor on the debate team.

She was more than that, actually. Excelling in competitions, she was named Oklahoma’s top high school debater.

Debating didn’t merely provide an outlet for Warren’s pugnaciousness. It earned her a place at George Washington University, in Washington, D.C., one of the few colleges to offer debate scholarships. Like many parents of modest means, hers didn’t exactly encourage her to be ambitious. Recounting her mother’s advice to her, Warren writes:

I needed to set my sights realistically. It was harder for a woman with a college education to find a husband…. If I really wanted to go to college, I could live at home, get a job, and go to school part-time somewhere close.

When Warren landed the scholarship at GW,

my mother responded to my news with equal parts pride and worry. She would say to her friends: “Well, she figured out how to go to college for free, so what could I say? But I don’t know if she’ll ever get married.”

In 1968, two years into her time at GW, she married Jim Warren, a fellow member of her high school debate team, who had just graduated from college and gotten a job with IBM. She quit college, moved to Texas with her husband, took his surname, and finished her BA at the University of Houston. When Jim was transferred to New Jersey, the family moved there. After a brief stint as a speech therapist in a public school, Warren had a daughter, whom she named Amelia. She settled into the role of homemaker—or so she thought. Soon, though, she felt frustrated. “I tried. I really tried,” she writes. “I wanted to be a good wife and mother, but I wanted to do something more. I felt deeply ashamed that I didn’t want to stay home full-time with my cheerful, adorable daughter.”

With the lukewarm endorsement of her husband, Warren enrolled in law school at Rutgers and did well. In 1978, she landed a position teaching contract law and legal writing at the University of Houston. By this point, she had a second child, a boy named Alex. When she called her parents to tell them about the new job, which came with an office and a tenure track, she got a mixed reaction:

My mother reminded me how tough this would be—two little children to care for, a house to manage, a husband to keep happy. I shouldn’t jeopardize how much I had by reaching too far. But my daddy gave me no such warnings. He said: “That’s my Betsy.”

In teaching at a law school, Warren had found her calling. During the 1980s, she and some colleagues carried out a memorable study of who went bankrupt. Most of the debtors who ended up before the bankruptcy court weren’t deadbeats or fraudsters, it turned out. They were normal middle-class families who had suffered a setback, such as an illness or the loss of a job, which meant they couldn’t meet the payments on their mortgages and credit card bills. In 1987, Warren moved to the University of Pennsylvania Law School, and, in 1995, to Harvard. Along the way, she shed one husband, Jim Warren, who had never quite gotten used to the fact that he had married a force of nature, and found another, Bruce Mann, a talented legal historian who, when Warren started commuting to and from Washington as part of the effort to prevent the changes in the bankruptcy law that the banks wanted, was content to stay at home with the dog.

It is hard to resist comparing Warren’s career to that of Hillary Clinton. On the face of it, the two women share some similarities. Both are highly intelligent Ivy League lawyers who hailed from Republican backgrounds—Warren’s father was a fan of Eisenhower—moved into liberal politics, and took on powerful interest groups. (In Clinton’s case, it was the health insurance companies.) But there the comparison ends.

From an early age, Clinton was a member of the American elite. Her father was a successful businessman. In high school, she was a National Merit Finalist. At Wellesley, she became the first student ever to deliver the commencement address. From there she went to Yale Law School, where she met Bill Clinton. By 1974, at the age of twenty-six, she was in Washington, working for the House Judiciary Committee, which was investigating Watergate. About the only hardship she was forced to endure was moving to Little Rock, Arkansas, with Bill, where the blow was softened by a post at the Rose Law Firm, the oldest and best-connected law firm in the state, whose clients included Tyson Foods, Walmart, and Stephens Inc., a big investment bank.

Advertisement

There is no reason to doubt Clinton’s commitment to the less fortunate. As a law student, she took on cases of child abuse and volunteered to provide free legal services to the poor. While at Yale, she researched the problems migrant laborers have in finding housing and health care. Inevitably, though, her perspective was that of the concerned observer.

Warren, for all her ultimate success, has much more personal experience of what America looks like from its lower and middle reaches. As a child, she saw the family’s station wagon repossessed. At twenty-six, pregnant with her second child, she graduated from Rutgers but couldn’t immediately find a job. “I would soon have two children, and I was heading home,” she writes. “I believed the working world was now closed to me forever.” By the time Warren got to the Ivy League, she was almost forty. When she went to work in Washington on a full-time basis, as a congressionally appointed overseer of the TARP bank bailout, she was close to sixty.

As a politician and activist, Warren’s great strength is that she retains the outsider’s perspective, and the outsider’s sense of moral outrage, which runs throughout A Fighting Chance. As she sees it, there are at least two sets of villains conspiring to rob ordinary Americans of the decent and improving livelihoods to which their hard work entitles them. The first are the big banks and other financial concerns, which burden people of modest means with credit card debt, lure them into reckless mortgages they can’t hope to repay, and chisel them with all sorts of outlandish fees.

In her book, she tells the stories of some of the victims of the housing bust. They include “Flora,” a feisty pensioner from the South who was tricked into taking out a low-interest mortgage, only to see the interest rate skyrocket, which forced her to declare bankruptcy and move into her car. And “Mr. Estrella,” a Marine Corps veteran who bought a house near his daughters’ school in Las Vegas, fell behind on his payments, saw his home sold at auction, and was ordered out with fourteen days’ notice.

In Warren’s worldview, the second set of miscreants is the Washington political class, which coddled the banks, encouraged their reckless lending, and eventually bailed them out on extremely generous terms, without any real effort to hold their senior executives accountable. She writes:

I don’t know for sure if anyone at the giant banks engaged in criminal activity in the months and years leading up to the financial meltdown. But that’s the point: I don’t think anyone knows for sure. Where were the full-scale public investigations? Where were the armies of auditors, seizing hard drives and poring over financial statements?… The government gives the banks the money but never puts major resources and manpower into finding out whether the sudden gaping hole in the banks’ balance sheets was caused, at least in part, by illegal activity. So the high-powered CEOs collect millions in bonuses, and Flora moves into her car.

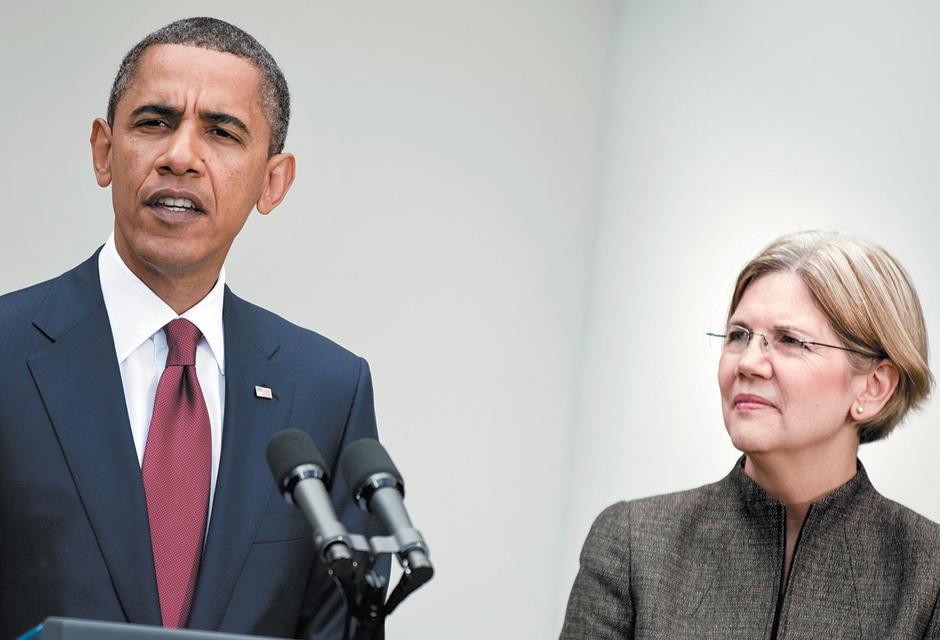

In a 2007 article, Warren called for the establishment of a new federal agency to protect the public from financial predators. Naturally, the banking industry and its allies weren’t enthusiastic about this proposal; but neither, initially, were many Democrats concerned with financial reform. To Tim Geithner, the Treasury secretary, Barney Frank, the head of the House Financial Services Committee, and Chris Dodd, the head of the Senate Banking Committee, the first task was to repair the banking system and beef up the existing regulatory regime to prevent another blowup. Consumer protection could wait. Warren disagreed, and, so, crucially, did President Obama. But even with his backing, it was a mighty task to get congressional approval for the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Given the hefty campaign contributions that the banks can make to candidates of their choice, many elected officials are almost as beholden to them as a customer with an overdue credit card bill. Warren describes a meeting she had, late in 2010, with Spencer Bachus, a congressman from Alabama, who was then the ranking Republican on the House Financial Services Committee. Bachus was known to be close to the banks, but when Warren met him, he expressed sympathy for the victims of the subprime mortgage crisis:

He spoke movingly about people who had been swindled; he really seemed to feel their pain. He concluded by saying that if he had more courage, he’d go after the people who did that to families. In other words, if he stood up for the families who’d been hurt, he could find himself sidelined in Congress by the leadership of his own party. I was stunned by his use of the word courage and his small, tight smile.

As Congressman Bachus ushered me out of his office, he took my arm and leaned close to me. “I’ll go after the consumer agency, but I hope you understand, it isn’t personal.” He said it in a quiet, gentle tone, with his accent twanging through each syllable….

I thought that it may not be personal for you, but it is personal for me.

Bachus is a charmer, no doubt. But to Warren and many other progressives, the perfidious GOP isn’t the only barrier to progress. The other problem is the cautious, pro-business wing of the Democratic Party, which, in the Obama administration, was represented by people like Geithner and Lawrence Summers, the head of the White House’s National Economic Council. In March 2009, Warren publicly criticized Geithner for failing to respond adequately to the mortgage foreclosure crisis. A few weeks later, Summers invited her to dinner at the Bombay Club, an Indian restaurant close to the White House.

The evening was a long one. Warren and Summers went back and forth on everything from the foreclosure crisis, to the bank bailout, to the deregulation of Wall Street during the 1990s, which Summers was a part of. “We didn’t agree on everything, but I give Larry full credit,” Warren writes. “I’ll take honest conversation and debate any day of the week over the duck-and-cover stuff I so often saw in Washington that spring.” She goes on:

Late in the evening, Larry leaned back in his chair and offered me some advice…. He teed it up this way: I had a choice. I could be an insider or I could be an outsider. Outsiders can say whatever they want. But people on the inside don’t listen to them. Insiders, however, get lots of access and a chance to push their ideas. People—powerful people—listen to what they have to say. But insiders also understand one unbreakable rule: They don’t criticize other insiders.

I had been warned.

Warren didn’t exactly take Summers’s advice; she didn’t exactly ignore it either. She continued to criticize the Treasury’s foreclosure program, which was clearly inadequate. Eventually, though, she agreed to work under Geithner at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, where she served as the interim head from September 2010 until July 2011.

Journalists scouring A Fighting Chance for more jabs at Geithner will be disappointed. “I felt as if one of us was standing on a snow-covered mountaintop and the other was crawling through Death Valley,” Warren writes. “Our views of the world—and the problems we saw—were that different.” But Warren also says that Geithner does a mean impression of the Three Stooges, and she reports that, once she was working for him at Treasury, he had her back. “I knew Tim hadn’t chosen me for this role. I knew I had been pushed on him by the president,” she recalls. “And I had begun to understand that he could probably take me down with carefully placed traps and leaks if he wanted to. But when he gave me his promise, I believed him.”

Largely because of her scorching criticism of the banks, Warren had little prospect of receiving Senate confirmation as the permanent head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. In 2011, President Obama nominated Richard Cordray, the former attorney general of Ohio, to replace her. Warren returned to Massachusetts and, before very long, she entered the 2012 race for the Senate seat that the Republican Scott Brown had won in a special election following Ted Kennedy’s death.

Warren devotes more than sixty pages to the Senate campaign—a trying ordeal during which she was forced to fend off Brown’s accusations that she had exaggerated her Native American heritage to help get a job at Harvard. (The university said its selection committee hadn’t considered her ethnicity in appointing her.) In the end, with the aid of local Democratic politicians, thousands of volunteers, and more than $40 million in campaign contributions, most of it in the form of small donations, she defeated her opponent handily.

Today, Warren’s 2012 campaign is perhaps most remembered for a YouTube clip of her speaking in Andover. Asked how the government should tackle the deficit, Warren said it should cut corporate loopholes and ask the rich to pay a bit more. And she went on:

There is nobody in this country who got rich on his own. Nobody. You built a factory out there? Good for you. But I want to be clear: You moved the goods to market on roads the rest of us paid for. You hired workers the rest of us paid to educate. You were safe in your factory because of police forces and fire forces the rest of us paid for. You didn’t have to worry that marauding bands would come and seize everything at your factory…. Now look, you built the factory and it turned into something terrific, or great idea? God bless. Keep a big hunk of it. But part of the underlying social contract is you take a hunk of that and pay forward for the next kid that comes along.

Given her waving arms and her reference to “marauding bands,” it was hardly surprising that Rush Limbaugh and other conservatives seized upon the video as evidence that she was some sort of dangerous radical. But as she points out in A Fighting Chance, her basic point was sound:

Without police, schools, roads, firefighters, and all the rest, where would those big corporations and “self-made” billionaires be? For capitalism to work, we all need each other.

If Warren has a big idea, this is it: the conception of society as an organic, mutually dependent whole. Admittedly, it’s not the most original notion. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, two new political creeds were built upon it: in this country, Progressivism; in Britain, New Liberalism. After World War II, the same conception underpinned European social democracy.

More recently, President Obama has invoked the progressive legacy. In Osawatomie, Kansas, in December 2011, he hailed Theodore Roosevelt, and seven months later, at a campaign event in Roanoke, Virginia, he said:

If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business, you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen.

One disappointing thing about Warren’s book is that she doesn’t really develop this idea, and its implications for policy. Caught up in her narrative, which is an engaging one, she rarely steps back and considers the bigger picture. And when she does, it tends to sound more like another campaign speech than a nuanced analysis of the situation. Saying that the system is rigged against the little guy who follows the rules only gets you so far.

Bill Clinton used almost exactly the same language, and so, more recently, did President Obama. Both of these presidents, although they disappointed many progressives, actually did quite a lot for the working poor and the squeezed middle class, albeit in somewhat surreptitious fashion. Thanks to the repeated expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit and the introduction of the Affordable Care Act, millions of American workers can now obtain generous subsidies to boost their wages and obtain health care coverage. That’s a big change from twenty-five years ago.

How can further progress be made? It’s not sufficient to cut the financial industry down to size, necessary though that is. If tomorrow the Justice Department indicted a dozen top Wall Street figures for their parts in the subprime caper, and also announced it was breaking up the too-big-to-fail banks—Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, and JPMorgan Chase among them—these measures wouldn’t increase the median family income, which has been stagnating for decades. They wouldn’t protect the pension benefits of public sector employees, which, in places like Boston and New York, and, indeed, Oklahoma City, are swallowing up an ever-increasing share of the budget. They wouldn’t resolve the question of how much taxes on the rich and on corporations can be raised without running into serious problems of capital flight and tax evasion. Or how American consumers are to be protected, not just from the banks, but from monopolies and emerging oligopolies in other parts of the economy, such as entertainment, airlines, and online communications.

Evidently, Warren decided that this wasn’t the place to delve into such matters, and maybe she was right. At its root, her message is ethical rather than economic: for her the American system is morally lost, and we need to set out on a new path. A Fighting Chance doesn’t lay out a comprehensive policy platform, but it confirms something Ted Kennedy realized back in 1998 when Warren came to his office and tried (successfully) to persuade him to oppose the reform of the bankruptcy law: she’s an indomitable battler for the underdog, and she doesn’t take no for an answer.

Those are excellent qualities for any progressive politician to have. Teddy Roosevelt, like Warren, talked in black-and-white terms, and he was much less of a policy wonk than she is. But he seized the day, rallied the populace against the plutocrats, and effected real changes. A century on, this could possibly be Warren’s moment. But will she seize it?

This Issue

May 22, 2014

How Memory Speaks

The Phony War?

-

*

See Eric Lipton, “Half of Congress Members Are Millionaires, Report Says,” The New York Times, January 10, 2014. ↩